Okinawa Island

| Native name: <span class="nickname" ">沖縄 | |

|---|---|

| |

Okinawa | |

| Geography | |

| Location | Pacific Ocean |

| Coordinates | 26°28′46″N 127°55′40″E / 26.47944°N 127.92778°ECoordinates: 26°28′46″N 127°55′40″E / 26.47944°N 127.92778°E |

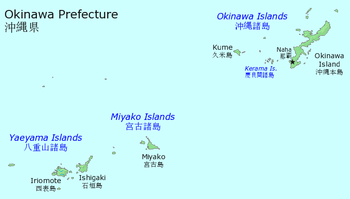

| Archipelago | Okinawa Islands |

| Area |

1,206.96 km2 (466.01 sq mi) as of 1 October 2015[1] |

| Highest elevation | 503 m (1,650 ft) |

| Highest point | Mount Yonaha |

| Administration | |

|

Japan | |

| Prefecture | Okinawa Prefecture |

| Largest settlement | Naha (pop. 321,077) |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 1,301,462 (Dec. 2014) |

| Pop. density | 1,083.6 /km2 (2,806.5 /sq mi) |

Okinawa Island (沖縄本島 Okinawa-hontō, alternatively 沖縄島 Okinawa-jima; Okinawan: 沖縄/うちなー Uchinaa or 地下/じじ jiji;[2] Kunigami: ふちなー Fuchináa) is the largest of the Okinawa Islands and the Ryukyu (Nansei) Islands of Japan. The island has an area of 1,206.96 square kilometers (466.01 sq mi). It is roughly 640 kilometres (400 mi) south of the rest of Japan, roughly the same distance off the coast of China, and 500 km (300 mi) north of Taiwan. The Greater Naha area, home to the capital (or more accurately—prefectural seat) of Okinawa Prefecture on the southwestern part of Okinawa Island, has roughly 800,000 of the island's 1.3 million residents, while the city itself is home to about 320,000.

Okinawa has been a critical strategic location for the United States Armed Forces since the end of World War II. The island hosts around 26,000 US military personnel, about half of the total complement of the United States Forces Japan, spread among 32 bases and 48 training sites. US bases in Okinawa played critical roles in the Korean War, Vietnam War, War in Afghanistan and Iraq War. The presence of the US military in Okinawa has caused political controversy both on the island and elsewhere in Japan.[3]

The island's population is known as one of the longest living people in the world,[4][5] in fact, there are 34 centenarians per 100,000 people, which is more than three times the rate of mainland Japan.

History

The time when human beings first appeared in Okinawa remains unknown.

Okinawa midden culture or shell heap culture is divided into the early shell heap period. In the former, it was a hunter-gatherer society, with wave-like opening Jomon pottery. In the latter part of the Jomon period, archaeological sites moved near the seashore, suggesting the engagement of people in fishery. In Okinawa, rice was not cultivated during the Yayoi period but began during the latter period of shell-heap age. Shell rings for arms made of shells obtained in the Sakishima Islands, namely Miyakojima and Yaeyama islands, were imported by Japan. In these islands, the presence of shell axes, 2500 years ago, suggests the influence of a southeastern-Pacific culture.[6][7]

After the midden culture, agriculture started about the 12th century, with the center moving from the seashore to higher places. This period is called the gusuku period. Gusuku is the term used for the distinctive Okinawan form of castles or fortresses. Many gusukus and related cultural remains in the Ryukyu Islands have been listed by UNESCO as World Heritage Sites under the title Gusuku Sites and Related Properties of the Kingdom of Ryukyu. There are three perspectives regarding the nature of gusukus: 1) a holy place, 2) dwellings encircled by stones, 3) a castle of a leader of people. In this period, porcelain trade between Okinawa and other countries became busy, and Okinawa became an important relay point in eastern-Asian trade. Ryukyuan kings, such as Shunten and Eiso, were considered to be important governors. An attempted Mongolian invasion in 1291 during the Eiso Dynasty ended in failure. Hiragana was imported from Japan by Ganjin in 1265. Noro, female shaman or priests (as in shintoism), appeared.

In 1429, King Shō Hashi completed the unification of the three kingdoms and founded one Ryūkyū Kingdom with its capital at Shuri Castle. The Chinese Ming dynasty sent 36 families from Fujian at the request of the Ryukyuan King. Their job was to manage maritime dealings in the kingdom in 1392 during the Hongwu Emperor's reign. Many Ryukyuan officials were descended from these Chinese immigrants, being born in China or having Chinese ancestors. They assisted the Ryukyuans in developing their technology and diplomatic relations.

In the 17th century, the kingdom was both a tributary of China and a tributary of Japan. Because China would not make a formal trade agreement unless a country was a tributary state, the kingdom was a convenient loophole for Japanese trade with China. When Japan officially closed off trade with European nations except the Dutch, Nagasaki and Ryūkyū became the only Japanese trading ports offering connections with the outside world.

In 1879, Japan annexed the entire Ryukyu archipelago.[8] Thus, the Ryūkyū han was abolished and replaced by Okinawa Prefecture by the Meiji government. The monarchy in Shuri was abolished and the deposed king Shō Tai (1843–1901) was forced to relocate to Tokyo.

Hostility against mainland Japan increased in the Ryūkyūs immediately after its annexation to Japan in part because of the systematic attempt on the part of mainland Japan to eliminate the Ryukyuan culture, including the language, religion, and cultural practices.

The island of Okinawa was the site of most of the ground warfare in the Battle of Okinawa during World War II, when U.S. Army and Marine Corps troops fought a long and bloody battle to capture Okinawa, so it could next be used as the major air force and troop base for the planned invasion of Japan. During this 82-day-long battle, about 95,000 Imperial Japanese Army troops and 12,510 Americans were killed. The Cornerstone of Peace at the Okinawa Prefecture Memorial Peace Park lists 149,193 persons of Okinawan origin - approximately one quarter of the civilian population - who either died or committed suicide during the Battle of Okinawa and the Pacific War.[9]

During the American military occupation of Japan (1945–52), which followed the Imperial Japanese surrender on September 2, 1945, in Tokyo Bay, the United States controlled Okinawa Island and the nearby Ryukyu islands and islets. These all remained in American military possession until June 17, 1972, with numerous U.S. Army, U.S. Marine Corps, and U.S. Air Force bases there.

In February 2010 an earthquake, measuring 7.0 on the Richter Scale, hit the island.

Demographics

As of September, 2009, the Japanese government estimates the population at 1,384,762,[10] which includes American military personnel and their families. The Okinawan language, called Uchinaguchi, is spoken mostly by the elderly.[11]

Whereas the northern half of Okinawa Island is sparsely populated, the south-central and southern parts of the island are markedly urbanized—particularly the city of Naha and the urban corridor stretching north from there to Okinawa City (Okinawa-shi).

There are six gusuku, medieval Okinawan fortresses, most of which now lie in ruins.[12]

Geography

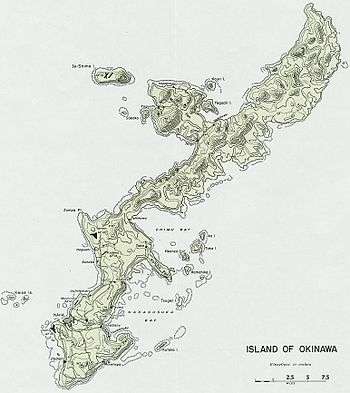

Okinawa is the fifth largest island in Japan (excluding the disputed islands north of Hokkaido). The island has an area of 1,201.03 square kilometers (463.72 sq mi). It is roughly 640 kilometres (400 mi) south of the rest of Japan. The island is connected to nearby islands by a land bridge: Yokatsu Peninsula (aka Katsuren Peninsula) is connected via the Mid-Sea Road to Henza Island, Miyagi Island, Ikei Island, and Hamahiga Island. Similarly, on the northeastern side, Toguchi Island, Kouri Island and Yagachi Island are connected by road to the main island.

Geology

The southern end of the island consists of uplifted coral reef, whereas the northern half has proportionally more igneous rock. The easily eroded limestone of the south has many caves, the most famous of which is Gyokusendō in Nanjō. An 850 m-long stretch is open to tourists.

Fauna

In the forests of Yanbaru, there are a small number of Yanbaru kuina (also known as the Okinawa rail), a small flightless bird that is close to extinction.

The Indian mongoose was introduced to the island to prevent the native habu pit viper from attacking the birds. It did not succeed in eliminating the habu, but instead preyed on birds, increasing the threat to the Okinawa rail.

Climate

The island's subtropical climate supports a dense northern forest and a rainy season occurring in the late spring.

Food

There are many local pubs (izakaya) and cafes that serve Okinawan cuisine and dishes, such as goya champuru (bitter melon stir fry), fu champuru (wheat gluten chanpuru), and tonkatsu (tenderized, breaded, fried pork cutlet). Okinawan soba is the signature dish and consists of wheat noodles served hot in a soup, usually with pork (rib or pork belly). This contrasts with the mainland soba, which is buckwheat noodles. Rafute, which is braised pork belly, is another popular Okinawan dish. American presence on the island has also led to some creative dishes such as taco rice, which is now a common meal served in bentos, and common use of spam.

Economy

Among the prefectures of Japan, Okinawa has the youngest and fastest-growing population, but has the lowest employment rate and average income. The island economy is primarily driven by tourism and the US military presence, with efforts in recent years to diversify into other sectors.[13]

Tourism

Tourist attractions include Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium (at one time the world's largest aquarium), Century Beach, Pineapple Park, the Orion Beer Factory and Hiji Falls. In recent years, Okinawa has become an increasingly popular destination for tourists from China and Southeast Asia.[14]

U.S. military

There are 32 U.S. military bases[15] located on Okinawa Island. In total, these bases occupy approximately 25% of the island's area. The major bases are Futenma,[16] Kadena, Hansen, Torii, Schwab, Foster, and Kinser. The bases primarily exist to serve Japanese and U.S. strategic interests, but are unpopular with most local residents[17] despite recent efforts to move the bases out of core areas following incidents involving military personnel and resultant protests (including the 1995 Okinawa rape incident).

Economically, the bases have been of declining importance, especially after Okinawan sovereignty returned to Japan, recently accounting for 4 to 5% of the island economy, but the economic impact may be double edged, the presence of the bases may be hampering investment (and tourism potential).[15][18] In 2012, an agreement was struck between the United States and Japan to reduce the number of U.S. military personnel on the island, moving 9,000 personnel to other locations and moving bases out of heavily populated Greater Naha, but 10,000 marines will remain on the island, along with other U.S. military units.[16][19] Attempts to completely close bases on the southern third of the island, where 90% of the population lives (all but about 120,000 people) has been impeded by both the U.S. desire that alternative locations be found where bases subject to closure could move to (e.g. Henoko Peninsula roughly mid-island), as well as by local Okinawan opposition to any suggested locations on the island (who demand no US troops at all anywhere on the island).[17] There exist also a smaller contingent of Japanese military bases on the island, to whom the local Okinawans also view as colonizers. Tokyo itself has a different view of the situation from that of local residents, who complain that despite being home to less than 1% of Japan's population and area, have to put up with the majority of Japan's U.S. military occupation.[20] In late December 2013, the governor of Okinawa, Hirokazu Nakaima, gave permission for land reclamation to begin for a new U.S. military base at Henoko reneging on previous promises, furthering the effort to consolidate American troop presence on the island, though away from urban Naha.[21] This resulted in his loss of the governorship.

Several former US military facilities in Okinawa have been re-developed as commercial areas, most notably the American Village in Chatan, Okinawa, which opened in 1998, and the Aeon Mall Okinawa Rycom in Kitanakagusuku, Okinawa, which opened in 2015.[14]

Transportation and logistics

Naha Airport is the main transportation hub for the Ryukyu Islands and has an increasingly large role in regional logistics. All Nippon Airways opened a cargo hub at the airport in 2009, providing overnight freight service between Japan and other Asian countries.[14]

Transportation

Naha Airport serves the island. There are multiple bus companies, such as Toyo Bus, Ryukyu Bus Kotsu, Naha Bus, and Okinawa Bus. There is also a monorail. The Okinawa Expressway is a toll road that runs from Naha to Nago, and has a speed limit of 80 kilometers per hour, the highest on the island. There are also many ferries to many of the nearby islands, such as Ie Shima. Tomarin Port in Naha, has ferries to nearby islands like Aguni Island, Tokashiki Island, Zamami Island. Naha Cruise Terminal, Naha city also has a cruise terminal.

Film

Teahouse of the August Moon (1956), starring Marlon Brando and Glenn Ford, was based on the hit Broadway play. The storyline of the play and the film were set in Okinawa, but actual filming took place in mainland Japan near Nara and in a studio in California.[22]

Okinawa was the setting for the 1974 Japanese science fiction kaiju film Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla, which featured a shisa dog as one of the monsters in the film; due to an awkward translation from Japanese to English, this monster is known in the film as King Caesar. Several scenes were filmed in the, at the time, recently discovered Gyokusendo caves.

Okinawa was also the setting for the 1986 film The Karate Kid, Part II, in which Mr. Miyagi (Pat Morita) returns home to Okinawa with his student Daniel LaRusso (Ralph Macchio). Although Okinawa was the setting for the film, only short scenes of the film were actually filmed in Okinawa. In the first Karate Kid movie, Mr. Miyagi refers to Okinawa and its origins of being a separate country from Japan.

See also

Photo gallery

-

Cliffs at Manzamo

-

Gusuku wall

-

Okinawa Island is the home of Tsuboya-yaki, pottery in the Ryūkyūan tradition.

-

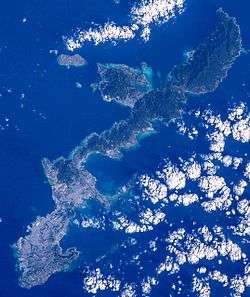

Okinawa Island from Space Shuttle Mission STS-43 (Earth Sciences and Image Analysis, NASA-Johnson Space Center)

-

Gusuku Ruins

-

Traditional Okinawan house

-

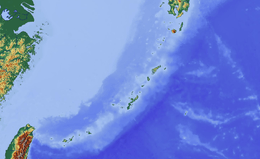

Map of Okinawa Prefecture showing location of Okinawa Island

-

Village of Onna

-

Pond

-

Farmland on Okinawa Island

-

A beach on Okinawa

References

- ↑ "Island Area - Statistical reports on the land area by prefectures and municipalities in Japan as of 2015" (PDF) (in Japanese). Geospatial Information Authority of Japan. 1 October 2015. p. 105. Retrieved 29 February 2016.

- ↑ 語彙詳細―首里・那覇方言. Okinawa Center of Language Study. Retrieved on 2014-12-02.

- ↑ Letman, Jon (24 August 2015). "70 years after the war, Okinawa protests new US military base". Al Jazeera America. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- ↑ Okinawa Exploration Backgrounds - Blue Zones

- ↑ Los secretos de la longevidad - National Geographic

- ↑ Arashiro Toshiaki High School History of Ryukyu, Okinawa, Toyo Kikaku, 2001, p12,ISBN 4-938984-17-2 p20

- ↑ Ito, Masami, "Between a rock and a hard place", Japan Times, May 12, 2009, p. 3.

- ↑ The Demise of the Ryukyu Kingdom: Western Accounts and Controversy. Ed by Eitetsu Yamagushi and Yoko Arakawa. Ginowan-City, Okinawa: Yonushorin, 2002.

- ↑ "The Cornerstone of Peace - number of names inscribed". Okinawa Prefecture. Retrieved 4 February 2011

- ↑ (Japanese) 沖縄県推計人口データ一覧(Excel形式). Pref.okinawa.jp. Retrieved on 2013-08-16.

- ↑ Central Okinawan language at Ethnologue (16th ed., 2009)

- ↑ "Gusuku Sites and Related Properties of the Kingdom of Ryukyu." UNESCO: World Heritage Convention.

- ↑ Martin, Alexander (13 November 2014). "Okinawa's Reinvention Enters Next Phase". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- 1 2 3 Yoshida, Reiji (17 May 2015). "Economics of U.S. base redevelopment sway Okinawa mindset". The Japan Times. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- 1 2 What awaits Okinawa 40 years after reversion?. The Japan Times. Retrieved on 2013-08-16.

- 1 2 Jaffe, Greg; Heil, Emily; Harlan, Chico (April 26, 2012), "U.S. comes to agreement with Japan to move 9,000 Marines off Okinawa", The Washington Post, washingtonpost.com, retrieved April 28, 2012

- 1 2 BBC News - Okinawa deal between US and Japan to move marines. Bbc.co.uk (2012-04-27). Retrieved on 2013-08-16.

- ↑ Hongo, Jun. (2012-05-16) Economic reliance on bases won't last, trends suggest. The Japan Times. Retrieved on 2013-08-16.

- ↑ Ito, Masami. (2012-04-28) U.S., Japan tweak marine exit plan. The Japan Times. Retrieved on 2013-08-16.

- ↑ http://archive.marinecorpstimes.com/article/20140814/NEWS/308140041/U-S-military-takes-1st-step-Okinawa-relocation

- ↑ AP (27 December 2013). "Okinawa Governor Gives Go-ahead For New US Base". DailyDigest. Retrieved 27 December 2013.

- ↑ Erickson, Hal. Military Comedy Films: A Critical Survey and Filmography of Hollywood Releases Since 1918. McFarland, 2012, p. 174.

External links

-

Okinawa Island travel guide from Wikivoyage

Okinawa Island travel guide from Wikivoyage