Operation Paperclip

Operation Paperclip was the United States Office of Strategic Services (OSS) program in which more than 1,500 Germans,[1] primarily scientists but also engineers and technicians, were brought to the United States from post-Nazi Germany for government employment starting in 1945 and increasing in the aftermath of World War II.[2] It was conducted by the Joint Intelligence Objectives Agency (JIOA) and in the context of the burgeoning Cold War. One purpose of Operation Paperclip was to deny German scientific expertise and knowledge to the Soviet Union[2] and the United Kingdom,[3] as well as to inhibit post-war Germany from redeveloping its military research capabilities. By comparison, the Soviet Union were even more aggressive in recruiting Germans: during Operation Osoaviakhim, Soviet military units forcibly (at gunpoint) recruited 2,000+ German specialists to the Soviet Union during one night.

The JIOA's recruitment of German scientists began after the Allied victory in Europe on May 8, 1945, but U.S. President Harry Truman did not formally order the execution of Operation Paperclip until August 1945. Truman's order expressly excluded anyone found "to have been a member of the Nazi Party, and more than a nominal participant in its activities, or an active supporter of Nazi militarism." However, those restrictions would have rendered ineligible most of the leading scientists whom the JIOA had identified for recruitment, among them rocket scientists Wernher von Braun, Kurt H. Debus, and Arthur Rudolph, as well as physician Hubertus Strughold, each earlier classified as a "menace to the security of the Allied Forces."[4]

The JIOA worked independently to circumvent President Truman's anti-Nazi order and the Allied Potsdam and Yalta agreements, creating false employment and political biographies for the scientists. The JIOA also expunged the scientists' Nazi Party memberships and regime affiliations from the public record. Once "bleached" of their Nazism, the scientists were granted security clearances by the U.S. government to work in the United States. The project's operational name of Paperclip was derived from the paperclips used to attach the scientists' new political personae to their "US Government Scientist" JIOA personnel files.[5]

Osenberg List

Nazi Germany found itself at a logistical disadvantage, having failed to conquer the USSR with Operation Barbarossa (June–December 1941), the Siege of Leningrad (September 1941 – January 1944), Operation Nordlicht ("Northern Light", August–October 1942), and the Battle of Stalingrad (July 1942 – February 1943). The failed conquest had depleted German resources, and its military-industrial complex was unprepared to defend the Großdeutsches Reich (Greater German Reich) against the Red Army's westward counterattack. By early 1943, the German government began recalling from combat a number of scientists, engineers, and technicians; they returned to work in research and development to bolster German defense for a protracted war with the USSR. The recall from frontline combat included 4,000 rocketeers returned to Peenemünde, in northeast coastal Germany.[6][7]

Overnight, Ph.D.s were liberated from KP duty, masters of science were recalled from orderly service, mathematicians were hauled out of bakeries, and precision mechanics ceased to be truck drivers.— Dieter K. Huzel, Peenemünde to Canaveral

The Nazi government's recall of their now-useful intellectuals for scientific work first required identifying and locating the scientists, engineers, and technicians, then ascertaining their political and ideological reliability. Werner Osenberg, the engineer-scientist heading the Wehrforschungsgemeinschaft (Military Research Association), recorded the names of the politically cleared men to the Osenberg List, thus reinstating them to scientific work.[8]

In March 1945, at Bonn University, a Polish laboratory technician found pieces of the Osenberg List stuffed in a toilet; the list subsequently reached MI6, who transmitted it to U.S. Intelligence.[9][10] Then U.S. Army Major Robert B. Staver, Chief of the Jet Propulsion Section of the Research and Intelligence Branch of the U.S. Army Ordnance Corps, used the Osenberg List to compile his list of German scientists to be captured and interrogated; Wernher von Braun, Germany's premier rocket scientist, headed Major Staver's list.[11]

Identification

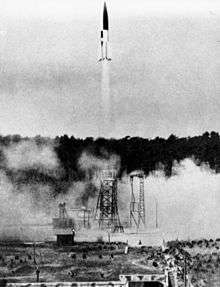

In Operation Overcast, Major Staver's original intent was only to interview the scientists, but what he learned changed the operation's purpose. On May 22, 1945, he transmitted to U.S. Pentagon headquarters Colonel Joel Holmes's telegram urging the evacuation of German scientists and their families, as most "important for [the] Pacific war" effort.[10] Most of the Osenberg List engineers worked at the Baltic coast German Army Research Center Peenemünde, developing the V-2 rocket. After capturing them, the Allies initially housed them and their families in Landshut, Bavaria, in southern Germany.

Beginning on July 19, 1945, the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) managed the captured ARC rocketeers under Operation Overcast. However, when the "Camp Overcast" name of the scientists' quarters became locally-known, the program was renamed Operation Paperclip in November 1945.[12] Despite these attempts at secrecy, later that year the press interviewed several of the scientists.[10][11][13]

Regarding Operation Alsos, Allied Intelligence described nuclear physicist Werner Heisenberg, the German nuclear energy project principal, as "worth more to us than ten divisions of Germans." In addition to rocketeers and nuclear physicists, the Allies also sought chemists, physicians, and naval weaponeers.[14]

Meanwhile, the Technical Director of the German Army Rocket Center, Wernher von Braun, was jailed at P.O. Box 1142, a military-intelligence black site in Fort Hunt, Virginia, in the United States. Since the prison was unknown to the international community, its operation by the US was in violation of the Geneva Convention of 1929, which the United States had ratified.[15] Although Von Braun's interrogators pressured him, he was not tortured; however, in 1944 another prisoner of war, U-boat Captain Werner Henke, had been shot and killed while climbing the fence at Fort Hunt.[16]

Capture and detention

Early on, the United States created the Combined Intelligence Objectives Subcommittee (CIOS). This provided the information on targets for the T-Forces that went in and targeted scientific, military and industrial installations (and their employees) for their know-how. Initial priorities were advanced technology, such as infrared, that could be used in the war against Japan; finding out what technology had been passed on to Japan; and finally to halt the research. A project to halt the research was codenamed "Project Safehaven", and it was not initially targeted against the Soviet Union; rather the concern was that German scientists might emigrate and continue their research in countries such as Spain, Argentina or Egypt, all of which had sympathized with Nazi Germany. In order to avoid the complications involved with the emigration of German scientists, the CIOS was responsible for scouting and kidnapping high profile individuals for the deprivation of technological advancements in nations outside of the US.

Much U.S. effort was focused on Saxony and Thuringia, which by July 1, 1945, would become part of the Soviet Occupation zone. Many German research facilities and personnel had been evacuated to these states, particularly from the Berlin area. Fearing that the Soviet takeover would limit U.S. ability to exploit German scientific and technical expertise, and not wanting the Soviet Union to benefit from said expertise, the United States instigated an "evacuation operation" of scientific personnel from Saxony and Thuringia, issuing orders such as:

On orders of Military Government you are to report with your family and baggage as much as you can carry tomorrow noon at 1300 hours (Friday, 22 June 1945) at the town square in Bitterfeld. There is no need to bring winter clothing. Easily carried possessions, such as family documents, jewelry, and the like should be taken along. You will be transported by motor vehicle to the nearest railway station. From there you will travel on to the West. Please tell the bearer of this letter how large your family is.

By 1947 this evacuation operation had netted an estimated 1,800 technicians and scientists, along with 3,700 family members. Those with special skills or knowledge were taken to detention and interrogation centers, such as one code-named DUSTBIN,[17] to be held and interrogated, in some cases for months.

A few of the scientists were gathered up in Operation Overcast, but most were transported to villages in the countryside where there were neither research facilities nor work; they were provided stipends and forced to report twice weekly to police headquarters to prevent them from leaving. The Joint Chiefs of Staff directive on research and teaching stated that technicians and scientists should be released "only after all interested agencies were satisfied that all desired intelligence information had been obtained from them".

On November 5, 1947, the Office of Military Government of the United States (OMGUS), which had jurisdiction over the western part of occupied Germany, held a conference to consider the status of the evacuees, the monetary claims that the evacuees had filed against the United States, and the "possible violation by the US of laws of war or Rules of Land Warfare". The OMGUS director of Intelligence R. L. Walsh initiated a program to resettle the evacuees in the Third World, which the Germans referred to as General Walsh's "Urwald-Programm" (jungle program), however this program never matured. In 1948, the evacuees received settlements of 69.5 million Reichsmarks from the U.S., a settlement that soon became severely devalued during the currency reform that introduced the Deutsche Mark as the official currency of western Germany.

John Gimbel concludes that the United States put some of Germany's best minds on ice for three years, therefore depriving the German recovery of their expertise.[18]

Scientists

In May 1945, the U.S. Navy "received in custody" Dr. Herbert A. Wagner, the inventor of the Hs 293 missile; for two years, he first worked at the Special Devices Center, at Castle Gould and at Hempstead House, Long Island, New York; in 1947, he moved to the Naval Air Station Point Mugu.[19]

In August 1945, Colonel Holger Toftoy, head of the Rocket Branch of the Research and Development Division of the U.S. Army's Ordnance Corps, offered initial one-year contracts to the rocket scientists; 127 of them accepted. In September 1945, the first group of seven rocket scientists (aerospace engineers) arrived at Fort Strong, located on Long Island in Boston harbor: Wernher von Braun, Erich W. Neubert, Theodor A. Poppel, August Schulze, Eberhard Rees, Wilhelm Jungert, and Walter Schwidetzky.[10]

Beginning in late 1945, three rocket-scientist groups arrived in the United States for duty at Fort Bliss, Texas, and at White Sands Proving Grounds, New Mexico, as "War Department Special Employees".[6]:27[12]

In 1946, the United States Bureau of Mines employed seven German synthetic fuel scientists at a Fischer-Tropsch chemical plant in Louisiana, Missouri.[20]

In early 1950, legal U.S. residency for some of the Project Paperclip specialists was effected through the U.S. consulate in Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua, Mexico; thus, German scientists legally entered the United States from Latin America.[6]:226[11]

Eighty-six aeronautical engineers were transferred to Wright Field, where the United States had Luftwaffe aircraft and equipment captured under Operation Lusty (Luftwaffe Secret Technology).[21]

The United States Army Signal Corps employed 24 specialists – including the physicists Georg Goubau, Gunter Guttwein, Georg Hass, Horst Kedesdy, and Kurt Lehovec; the physical chemists Rudolf Brill, Ernst Baars, and Eberhard Both; the geophysicist Helmut Weickmann; the optician Gerhard Schwesinger; and the engineers Eduard Gerber, Richard Guenther, and Hans Ziegler.[22]

In 1957, Fritz Karl Preikschat, taken to Russia through Operation Osoaviakhim, accepted a U.S. employment contract from the U.S. Air Force and ended up at Boeing, making him perhaps the only German engineer to contribute to both sides of the Space Race (Russia and U.S.).

In 1959, 94 Operation Paperclip men went to the United States, including Friedwardt Winterberg and Friedrich Wigand.[19] Throughout its operations to 1990, Operation Paperclip imported 1,600 men, as part of the intellectual reparations owed to the United States and the UK, some $10 billion in patents and industrial processes.[19][23]

During the decades after they were included in Operation Paperclip, some scientists were investigated because of their activities during World War II. Arthur Rudolph was deported in 1984, but not prosecuted, and West Germany granted him citizenship.[24] Similarly, Georg Rickhey, who came to the United States under Operation Paperclip in 1946, was returned to Germany to stand trial at the Dora Trial in 1947; he was acquitted, and returned to the United States in 1948, eventually becoming a U.S. citizen.[25] The aeromedical library at Brooks Air Force Base in San Antonio, Texas, had been named after Hubertus Strughold in 1977. However, it was later renamed because documents from the Nuremberg War Crimes Tribunal linked Strughold to medical experiments in which inmates from Dachau were tortured and killed.[26]

Key figures

- Rocketry

- Rudi Beichel, Magnus von Braun, Wernher von Braun, Werner Dahm, Konrad Dannenberg, Kurt H. Debus, Walter Dornberger, Ernst R. G. Eckert, Krafft Arnold Ehricke, Barret A. Lee, Otto Hirschler, Hermann H. Kurzweg, Fritz Mueller, Eberhard Rees, Gerhard Reisig, Georg Rickhey, Werner Rosinski, Ludwig Roth, Arthur Rudolph, Ernst Steinhoff, Ernst Stuhlinger, Bernhard Tessmann, and Georg von Tiesenhausen (see List of German rocket scientists in the US).

- Aeronautics

- Sighard F. Hoerner, Siegfried Knemeyer, Alexander Martin Lippisch, Hans Multhopp, Hans von Ohain, and Kurt Tank

- Medicine – biological weapons, chemical weapons, human experimentation, human factors in space medicine

- Hans Antmann, Kurt Blome, Erich Traub, Walter Schreiber, Richard Lindenberg and Hubertus Strughold[21]

- Electronics

- Hans Hollmann, Kurt Lehovec, Johannes Plendl, Heinz Schlicke and Hans K. Ziegler

- Intelligence

- Reinhard Gehlen, Otto von Bolschwing

Similar operations

- APPLEPIE: Project to capture and interrogate key Wehrmacht, RSHA AMT VI, and General Staff officers knowledgeable of the industry and economy of the USSR.[27]

- DUSTBIN (counterpart of ASHCAN): An Anglo-American military intelligence operation established first in Paris, then in Kransberg Castle, at Frankfurt.[28][29]:314

- ECLIPSE (1944): An unimplemented Air Disarmament Wing plan for post-war operations in Europe for destroying V-1 and V-2 missiles.[29][30]:44

- Safehaven: US project within ECLIPSE meant to prevent the escape of Nazi scientists from Allied-occupied Germany.[11]

- Field Information Agency; Technical (FIAT): US Army agency for securing the "major, and perhaps only, material reward of victory, namely, the advancement of science and the improvement of production and standards of living in the United Nations, by proper exploitation of German methods in these fields"; FIAT ended in 1947, when Operation Paperclip began functioning.[29]:316

- On April 26, 1946, the Joint Chiefs of Staff issued JCS Directive 1067/14 to General Eisenhower instructing that he "preserve from destruction and take under your control records, plans, books, documents, papers, files and scientific, industrial and other information and data belonging to . . . German organizations engaged in military research";[10]:185 and that, excepting war-criminals, German scientists be detained for intelligence purposes as required.[31]

- National Interest/Project 63: Job placement assistance for Nazi engineers at Lockheed, Martin Marietta, North American Aviation, and other aeroplane companies, whilst American aerospace engineers were being laid off work.[19]

- Operation Alsos, Operation Big, Operation Epsilon, Russian Alsos: Soviet, American and British efforts to capture German nuclear secrets, equipment, and personnel.

- Operation Backfire: A British effort at capturing rocket and aerospace technology from Cuxhaven.

- Fedden Mission: British mission to gain technical intelligence concerning advanced German aircraft and their propulsion systems.

- Operation Lusty: US efforts to capture German aeronautical equipment, technology, and personnel.

- Operation Osoaviakhim (sometimes transliterated as "Operation Ossavakim"), a Soviet counterpart of Operation Paperclip, involving German technicians, managers, skilled workers and their respective families who were relocated to the USSR in October 1946.[32]

- Operation Surgeon: British operation for denying German aeronautical expertise from the USSR, and for exploiting German scientists in furthering British research.[33]

- Special Mission V-2: April–May 1945 US operation, by Maj. William Bromley, that recovered parts and equipment for 100 V-2 missiles from a Mittelwerk underground factory in Kohnstein within the Soviet zone. Maj. James P. Hamill co-ordinated the transport of the equipment on 341 railroad cars with the 144th Motor Vehicle Assembly Company, from Nordhausen to Erfurt, just before the Soviets arrived.[34] (see also Operation Blossom, Broomstick Scientists, Hermes project, Operations Sandy and Pushover)

- Target Intelligence Committee: US project to exploit German cryptographers.

See also

- Brain drain

- Operation Osoaviakhim

- List of former Nazi Party members

- Carmel Offie

- Fort Bliss

- Operation Bloodstone

- Operation Lusty — targeting advanced aircraft of the defeated Luftwaffe

- Ratlines (World War II)

- Unit 731 — Japanese human experimenters recruited for their biological weapons technology.

- Upper Atmosphere Research Panel

Notes

- ↑ Jacobsen, Annie (2014). Operation Paperclip : the secret intelligence program to bring Nazi scientists to America. New York: Little, Brown and Company. p. Prologue, ix. ISBN 0316221058.

- 1 2 "Joint Intelligence Objectives Agency". U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved October 9, 2008.

- ↑ The Secret War, 1978, Brian Johnson, p184

- ↑ Ford, Brian (2011). Secret Weapons: Death Rays, Doodlebugs and Churchill's Golden Goose. Osprey Publishing. p. 144. ISBN 9781780967219.

- ↑ Project Paperclip: German Scientists and the Cold War, 1975, Clarence G. Lasby, et al.

- 1 2 3 Huzel, Dieter K (1960). Peenemünde to Canaveral. Englewood Cliffs NJ: Prentice Hall. pp. 27,226.

- ↑ Braun, Wernher von; Ordway III; Frederick I (1985) [1975]. Space Travel: A History. & David Dooling, Jr. New York: Harper & Row. p. 218. ISBN 0-06-181898-4.

- ↑ Forman, Paul; Sánchez-Ron, José Manuel (1996). National Military Establishments and the Advancement of Science and Technology. Boston Studies in the Philosophy of Science. Kluwer Academic Publishers. p. 308.

- ↑ MI6: Inside the Covert World of Her Majesty's Secret Intelligence Service (2000), by Steven Dorril, p. 138.

- 1 2 3 4 5 McGovern, James (1964). Crossbow and Overcast. New York: W. Morrow. pp. 100, 104, 173, 207, 210, 242.

- 1 2 3 4 Ordway, Frederick I, III; Sharpe, Mitchell R (1979). The Rocket Team. Apogee Books Space Series 36. New York: Thomas Y. Crowell. pp. 310, 313, 314, 316, 325, 330, 406. ISBN 1-894959-00-0.

- 1 2 Laney, Monique (2015). German Rocketeers in the Heart of Dixie: Making Sense of the Nazi Past During the Civil Rights Era. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-300-19803-4.

- ↑ Boyne, Walter J. (June 2007). "Project Paperclip". Air Force. Air Force Association. Retrieved October 17, 2008.

- ↑ Naimark, Norman M (1979). The Russians in Germany; A History of the Soviet Zone of Occupation, 1945–1949. Harvard University Press. p. 207. ISBN 0-674-78406-5.

- ↑ "Convention relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War. Geneva, 27 July 1929. Part VIII : Execution of the convention. Section II : Organization of control. Article 86". ICRC. Retrieved August 7, 2016.

- ↑ Dvorak, Petula (October 6, 2007). "Fort Hunt's Quiet Men Break Silence on WWII". The Washington Post. Retrieved January 11, 2008.

- ↑ Note: Located first in Paris and then moved to Kransberg Castle outside Frankfurt.

- ↑ "U.S. Policy and German Scientists: The Early Cold War", Political Science Quarterly, Vol. 101, No. 3, (1986), pp. 433–451

- 1 2 3 4 Hunt, Linda (1991). Secret Agenda: The United States Government, Nazi Scientists, and Project Paperclip, 1945 to 1990. New York: St.Martin's Press. pp. 6,21,31,176,204,259. ISBN 0-312-05510-2.

- ↑ "Fischer-Tropsch.org". Fischer-Tropsch.org. Retrieved December 22, 2011.

- 1 2 "The End of World War II". (television show, Original Air Date: 2-17-05). A&E. Retrieved June 4, 2007.

- ↑ Fred Carl. "Operation Paperclip and Camp Evans". Campevans.org. Retrieved December 22, 2011.

- ↑ Naimark. 206 (Naimark cites Gimbel, John Science Technology and Reparations: Exploitation and Plunder in Postwar Germany) The $10 billion compare to the 1948 US GDP $258 billion, and to the total Marshall plan (1948–52) expenditure of $13 billion, of which Germany received $1.4 billion (partly as loans).

- ↑ Hunt, Linda (May 23, 1987). "NASA's Nazis". Literature of the Holocaust.

- ↑ Michael J. Neufeld (2008). Von Braun: Dreamer of Space, Engineer of War Vintage Series. Random House, Inc. ISBN 978-0-307-38937-4.

- ↑ Walker, Andres (November 21, 2005). "Project Paperclip: Dark side of the Moon". BBC news. Retrieved October 18, 2008.

- ↑ "List Of Terms, Code Names, Operations, and Other Search Terminology To Assist Review and Identification Activities Required by the Act". U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved December 19, 2008.

- ↑ Buchholz, Dr. Annemarie (2003). "The New Form of Government: Bombocracy". Current Concerns. Switzerland. Retrieved October 18, 2008.

- 1 2 3 Ziemke, Earl F (1990) [1975]. "Chapter XI:Getting Ready for "The Day"". The U.S. Army in the Occupation of Germany 1944–1946. Washington DC: United States Army Center of Military History. p. 163. CMH Pub 30-6.

- ↑ Cooksley, Peter G (1979). Flying Bomb. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 44.

- ↑ Beyerchen, Alan. "German Scientists and Research Institutions in Allied Occupation Policy". History of Education Quarterly, Vol. 22, No. 3, Special Issue: Educational Policy and Reform in Modern Germany. (Autumn, 1982), pp. 289–299. NOTE: Much of the FIAT information was adapted commercially, to the degree that the office of the Assistant Secretary of State for Occupied Areas requested that the peace treaty with Germany be redacted to protect US industry from lawsuits.

- ↑ Pennacchio, Charles F. (Fall 1995). "The East German Communists and the Origins of the Berlin Blockade Crisis" (DOC). East European Quarterly. 29 (3). Retrieved June 29, 2010.

[...] October 21, 1946, marked the initiation of "Operation Ossavakim," which forcibly transferred to Soviet soil thousands of German technicians, managers and skilled personnel, along with their family members and the industrial tools they would operate.

- ↑ "UK 'fears' over German scientists" BBC NewsUK March 31, 2006

- ↑ Breuer, William B. (2000). Top Secret Tales of World War II. Wiley. pp. 220–224. ISBN 0-471-35382-5.

References

- Yves Beon, Planet Dora. Westview Press, 1997. ISBN 0-8133-3272-9.

- Giuseppe Ciampaglia: "Come ebbe effettivo inizio a Roma l'Operazione Paperclip". Roma 2005. In: Strenna dei Romanisti 2005. Edit. Roma Amor

- Henry Stevens, Hitler's Suppressed and Still-Secret Weapons, Science and Technology. Adventures Unlimited Press, 2007. ISBN 1-931882-73-8

- John Gimbel, "Science Technology and Reparations: Exploitation and Plunder in Postwar Germany" Stanford University Press, 1990 ISBN 0-8047-1761-3

- Linda Hunt, Arthur Rudolph of Dora and NASA, Moment 4, 1987 (Yorkshire Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament)

- Linda Hunt, Secret Agenda:The United States Government, Nazi Scientists, and Project Paperclip, 1945 to 1990. St Martin's Press – Thomas Dunne Books, 1991. ISBN 0-312-05510-2

- Linda Hunt, U.S. Coverup of Nazi Scientists The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. April 1985.

- Matthias Judt; Burghard Ciesla, Technology Transfer Out of Germany After 1945 Harwood Academic Publishers, 1996. ISBN 3-7186-5822-4

- Michael C. Carroll, Lab 257: The Disturbing Story of the Government's Secret Germ Laboratory. Harper Paperbacks, 2005. ISBN 0-06-078184-X

- John Gimbel "U.S. Policy and German Scientists: The Early Cold War", Political Science Quarterly, Vol. 101, No. 3 (1986), pp. 433–51

- Clarence G., Lasby Project Paperclip: German Scientists and the Cold War Scribner (February 1975) ISBN 0-689-70524-7

- Christopher Simpson, Blowback: America's Recruitment of Nazis and Its Effects on the Cold War (New York: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1988)

- Wolfgang W. E. Samuel American Raiders: The Race to Capture the Luftwaffe's Secrets (University Press of Mississippi, 2004)

- Koerner, Steven T. "Technology Transfer from Germany to Canada after 1945: A Study in Failure?". Comparative Technology Transfer and Society, Volume 2, Number 1, April 2004, pp. 99–124

- John Farquharson "Governed or Exploited? The British Acquisition of German Technology, 1945–48" Journal of Contemporary History, Vol. 32, No. 1 (Jan. 1997), pp. 23–42

- 1995 Human Radiation Experiments Memorandum: Post-World War II Reccruitment of German Scientists – Project Paperclip

- Employment of German scientists and technicians: denial policy UK National archives releases March 2006.

- "Objective List of German and Austrian Scientists" (Microsoft Word). Joint Intelligence Objectives Agency. Retrieved April 10, 2007.

Further reading

- Jacobsen, Annie (2014). Operation Paperclip: The Secret Intelligence Program that Brought Nazi Scientists to America. New York: Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 9780316221047. OCLC 827257574. Retrieved February 17, 2014.

- Lichtblau, Eric (2014). The Nazis Next Door: How America Became a Safe Haven for Hitler's Men. Mariner Books. ISBN 0544577884

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Operation Paperclip. |

- In Cold War, U.S. Spy Agencies Used 1,000 Nazis. Eric Lichtblau for The New York Times. October 26, 2014.

- The Nazis Next Door: Eric Lichtblau on how the CIA & FBI Secretly Sheltered Nazi War Criminals – video report by Democracy Now!, October 31, 2014