Paraganglioma

| Paraganglioma | |

|---|---|

| |

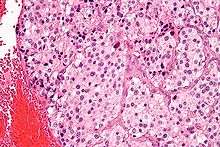

| Micrograph of a carotid body tumor (a type of paraganglioma). | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | oncology |

| ICD-10 | C75.4, C75.5, D35.5, D35.6, D44.6, D44.7 |

| ICD-9-CM | 194.5, 194.6, 227.5, 227.6, 237.3 |

| ICD-O | M8680/0 - M8693/9 |

| DiseasesDB | 33480 |

| eMedicine | med/2994 |

| MeSH | D010235 |

A paraganglioma is a rare neuroendocrine neoplasm that may develop at various body sites (including the head, neck, thorax and abdomen). About 97% are benign and cured by surgical removal; the remaining 3% are malignant because they are able to produce distant metastases. "Paraganglioma" is now the most-widely accepted term for these lesions, that have been also described as: glomus tumor, chemodectoma, perithelioma, fibroangioma, and sympathetic nevi.[1]

Cellular origin and classification

Paragangliomas originate from paraganglia in chromaffin-negative glomus cells derived from the embryonic neural crest, functioning as part of the sympathetic nervous system (a branch of the autonomic nervous system). These cells normally act as special chemoreceptors located along blood vessels, particularly in the carotid bodies (at the bifurcation of the common carotid artery in the neck) and in aortic bodies (near the aortic arch).

Accordingly, paragangliomas are categorised as originating from a neural cell line in the World Health Organization classification of neuroendocrine tumors. In the categorization proposed by Wick, paragangliomas belong to group II.[2] Given the fact that they originate from cells of the orthosympathetic system, paragangliomas are closely related to pheochromocytomas, which however are chromaffin-positive.

Clinical presentation

Most paragangliomas are either asymptomatic or present as a painless mass. While all contain neurosecretory granules, only in 1–3% of cases is secretion of hormones such as catecholamines abundant enough to be clinically significant; in that case manifestations often resemble those of pheochromocytomas (intra-medullary paraganglioma).

Inheritance

About 75% of paragangliomas are sporadic; the remaining 25% are hereditary (and have an increased likelihood of being multiple and of developing at an earlier age). Mutations of the genes for the succinate dehydrogenase, SDHD (previously known as PGL1), SDHA, SDHC (previously PGL3) and SDHB have been identified as causing familial head and neck paragangliomas. Mutations of SDHB play an important role in familial adrenal pheochromocytoma and extra-adrenal paraganglioma (of abdomen and thorax), although there is considerable overlap in the types of tumors associated with SDHB and SDHD gene mutations. Paragangliomas may also occur in MEN type 2A and 2B. They are seen in at a higher incidence in people living at high altitude. Other genes related to familiar paraganglioma are SDHAF2, VHL, NF1, TMEM127 and MAX.

Pathology

The paragangliomas appear grossly as sharply circumscribed polypoid masses and they have a firm to rubbery consistency. They are highly vascular tumors and may have a deep red color.

On microscopic inspection, the tumor cells are readily recognized. Individual tumor cells are polygonal to oval and are arranged in distinctive cell balls, called Zellballen.[3] These cell balls are separated by fibrovascular stroma and surrounded by sustentacular cells.

By light microscopy, the differential diagnosis includes related neuroendocrine tumors, such as carcinoid tumor, neuroendocrine carcinoma, and medullary carcinoma of the thyroid.

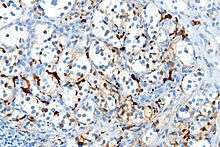

With immunohistochemistry, the chief cells located in the cell balls are positive for chromogranin, synaptophysin, neuron specific enolase, serotonin, neurofilament and Neural cell adhesion molecule; they are S-100 protein negative. The sustentacular cells are S-100 positive and focally positive for glial fibrillary acidic protein. By histochemistry, the paraganglioma cells are argyrophilic, periodic acid Schiff negative, mucicarmine negative, and argentaffin negative.

Sites of origin

About 85% of paragangliomas develop in the abdomen; only 12% develop in the chest and 3% in the head and neck region (the latter are the most likely to be symptomatic). While most are single, rare multiple cases occur (usually in a hereditary syndrome). Paragangliomas are described by their site of origin and are often given special names:-

- Carotid paraganglioma (carotid body tumor): Is the most common of the head and neck paragangliomas. It usually presents as a painless neck mass, but larger tumors may cause cranial nerve palsies, usually of the vagus nerve and hypoglossal nerve.

- Glomus tympanicum and Glomus jugulare: Both commonly present as a middle ear mass resulting in tinnitus (in 80%) and hearing loss (in 60%). The cranial nerves of the jugular foramen may be compressed, resulting swallowing difficulty, or ipsilateral weakness of the upper trapezius and sternocleiodomastoid muscles (from compression of the spinal accessory nerve). These patients present with a reddish bulge behind an intact ear drum. This condition is also known as the "Red drum". On application of pressure to the external ear canal with the help of a pneumatic ear speculum the mass could be seen to blanch. This sign is known as "Brown's sign".

- Vagal paraganglioma: These are the least common of the head and neck paragangliomas. They usually present as a painless neck mass, but may result in dysphagia and hoarseness.

- Pulmonary paraganglioma: These occur in the lung and may be either single or multiple.[4]

- Other sites: Rare sites of involvement are the larynx, nasal cavity, paranasal sinuses, thyroid gland, and the thoracic inlet, as well as the bladder in extremely rare cases.

Treatment

The main treatment modalities are surgery, embolization[5] and radiotherapy.[6]

Additional images

Micrograph of a carotid body tumor.

Micrograph of a carotid body tumor. Glomus Jugulare Tumor.

Glomus Jugulare Tumor._in_a_patient_with_VHL.jpg) Ectopic functional paraganglioma (glomus jugulare) in a patient with VHL. T2 weighted MRI at the same location demonstrates a high signal mass consistent with a paraganglioma. Extra adrenal paragangliomas can be found in VHL (arrow).

Ectopic functional paraganglioma (glomus jugulare) in a patient with VHL. T2 weighted MRI at the same location demonstrates a high signal mass consistent with a paraganglioma. Extra adrenal paragangliomas can be found in VHL (arrow). S100 immunostain highlighting the sustentacular cells in a paraganglioma.

S100 immunostain highlighting the sustentacular cells in a paraganglioma.

See also

References

- ↑ Rao AB, et al. (1999). "Paragangliomas of the Head and Neck: Radiologic-Pathologic Correlation". Radiographics. 119 (6): 1605–32. doi:10.1148/radiographics.19.6.g99no251605. PMID 10555678.

- ↑ Wick MR (2000). "Neuroendocrine neoplasia. Current concepts". Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 113 (3): 331–5. doi:10.1309/ETJ3-QBUK-13QD-J8FP. PMID 10705811.

- ↑ Kairi-Vassilatou E, Argeitis J, Nika H, Grapsa D, Smyrniotis V, Kondi-Pafiti A (2007). "Malignant paraganglioma of the urinary bladder in a 44-year-old female: clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study of a rare entity and literature review". Eur. J. Gynaecol. Oncol. 28 (2): 149–51. PMID 17479683.

- ↑ da Silva, RA; Gross JL; Haddad FJ; et al. (February 2006). "Primary pulmonary paraganglioma: case report and literature review". Clinics (São Paulo). 61 (1): 83–86. doi:10.1590/S1807-59322006000100015. PMID 16532231.

- ↑ Carlsen CS, Godballe C, Krogdahl AS, Edal AL (2003). "Malignant vagal paraganglioma: report of a case treated with embolization and surgery". Auris Nasus Larynx. 30 (4): 443–6. doi:10.1016/S0385-8146(03)00066-X. PMID 14656575.

- ↑ Pitiakoudis M, Koukourakis M, Tsaroucha A, Manavis J, Polychronidis A, Simopoulos C (2004). "Malignant retroperitoneal paraganglioma treated with concurrent radiotherapy and chemotherapy". Clinical oncology (Royal College of Radiologists (Great Britain)). 16 (8): 580–1. doi:10.1016/j.clon.2004.08.002. PMID 15630855.

External links

- Clinical Trial information for patients with Paraganglioma

- (Description with pictures)

- GeneReviews/NCBI/NIH/UW entry on Hereditary Paraganglioma-Pheochromocytoma Syndromes

- (Bilateral Carotid Paraganglioma)