Paranja

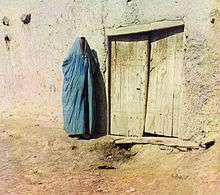

Paranja (or Paranji) from فرنجية (Паранджа[1]) is a traditional Central Asian robe of women and girls, that, when worn, shrouds the body and head.[2][3] It is also known as the "burqa" in other languages. It is similar in basic style and function to other regional styles such as the Afghan chadari. The chasmband and paranja were used by women completely cover themselves in cities in Central Asia.[4]

In Central Asian sedentary Muslim areas (today Uzbekistan and Tajikistan), women wore veils which shrouded the entire face. These were called paranja[2] or faranji. The traditional veil in Central Asia worn before modern times was the faranji,[5] but it was banned by the Soviet Communists.[6] The Tajikistan President Emomali has misleadingly tried to claim that veils were not part of Tajik culture.[7] The veil was attacked by the government of Atambaev, the Kyrgyz President.[8][9][10]

The part that covered the face, known as the chachvan (or chachvon), was heavy in weight and made from horsehair. It was especially prevalent among urban Uzbeks and Tajiks. The paranja was worn in Khorezm.[11][12] It was also worn during the Shaybanids' rule.[13]

In the 1800s, women were obligated to wear paranja when outside the house.[14]

Paranji and chachvon were by 1917 common among urban Uzbek women of the southern river basins. This was less frequently worn in the rural areas, and scarcely at all on the nomadic steppe. [15]

The unveiling by the Soviets was called the "hujum" in the Uzbek SSR.[16]

The paranja was worn in Central Asia in cities. The paranjas were burned on orders of the Communist Soviets. Due to the fact that paranjas were worn by Tajiks and Uzbeks, in Bukhara none of the women could be seen by Lord Curzon in his travel there in 1886.[17]

Lord Curzon remarked "I have frequently been asked since my return - it is the question which an Englishman always seems to ask first - what the women of Bokhara were like? I am utterly unable to say. I never saw the features of one between the ages of ten and fifty. The little girls ran about unveiled, in loose silk frocks, and wore their hair in long plaits escaping from a tiny skull-cap. Similarly the old hags were allowed to exhibit their innocuous charms, on the ground, I suppose, that they could excite no dangerous emotions. But the bulk of the female population were veiled in a manner that defied and even repelled scrutiny. For not only were the features concealed behind a heavy black horsehair veil, falling from the top of the head to the bosom, but their figures were loosely wrapped up in big blue cotton dressing-gowns, the sleeves of which are not used but are pinned together over the shoulders at the back and hang down to the ground, where under this shapeless mass of drapery appear a pair of feet encased in big leather boots."[18] [19] [20] [21][22]

"When in the streets, they draw a covering over their heads, and are seen clad in dark gowns of deep blue, with the empty sleeves hanging suspended to their backs, so that observed from behind, the fair ones of Bokhara may be mistaken for clothes wandering about. From the head down to the bosom they wear a veil made of horsehair, of a texture which we in Europe would regard as too bad and coarse for a sieve, and the friction of which upon cheek or nose must be anything but agreeable. Their chaussures consist of coarse heavy boots, in which their little feet are fixed, enveloped in a mass of leather. Such a costume is not in itself attractive; but even so attired, they dare not be seen too often in the streets. Ladies of rank and good character never venture to show themselves in any public place or bazaar. Shopping is left to the men ; and whenever any extraordinary emergency obliges a lady to leave the house and to pay visits, it is regarded as bon ton for her to assume every possible appearance of decrepitude, poverty, and age.

To send forth a young lady in her eighteenth or twentieth year, in all the superabundant energy of youth, supported upon a stick, and thus muffled up, in the sole view that the assumption of the characteristics of advanced life may spare her certain glances, may be justly deemed the ne plus ultra of tyranny and hypocrisy. These erroneous notions of morality are to be met with, more or less, everywhere in the East; but nowhere does one find such striking examples of Oriental exaggeration as in that seat of ancient Islamite civilization, Bokhara."[23][24]

"This becomes, after a while, one of the most disagreeable features of Khiva. Men's faces, nothing but men's faces for weeks and months, until you long for the sight of a woman's face, as you do for green grass and flowers in the desert."[25][26][27]

The chachvan veil and paranjas were used by women of the Tajiks and Uzbek Muslims since when they went out of their homes in the cities they were required to wear it in the 1800s. Chachvans and paranjas were banned by the Soviet Communists.[28]

Russia's October Revolution encouraged a liberation of women, and sought to discourage or ban the veil, as well as the paranja.[29] J. A. Macgahen saw few women and for most of his time there he only saw men in khiva, calling it a "disagreeable feature". The Soviet Union tried to deveil women of the paranja, but the veil wearing Muslim women responded by killing the women who were sent to take their veils off.[30] Uzbeks violently opposed the anti-paranja, anti-child marriage and anti-polygamy campaign which was started by the Soviet Union.[31]

Gallery

References

- ↑ http://www.jnsm.com.ua/cgi-bin/u/book/mySIS.pl?showSISid=46609864-4036&pageSISid=3&action=showSIS&h=f

- 1 2 Ahmad Hasan Dani; Vadim Mikhaĭlovich Masson; Unesco (1 January 2003). History of Civilizations of Central Asia: Development in contrast : from the sixteenth to the mid-nineteenth century. UNESCO. pp. 357–. ISBN 978-92-3-103876-1.

- ↑ Kamoludin Abdullaev; Shahram Akbarzaheh (27 April 2010). Historical Dictionary of Tajikistan. Scarecrow Press. pp. 129–. ISBN 978-0-8108-6061-2.

- ↑ Krueger, Carolyn (2011). "Uzbek Dance A Short History". Gulistan Dance Theater.

- ↑ Kamoludin Abdullaev; Shahram Akbarzaheh (27 April 2010). Historical Dictionary of Tajikistan. Scarecrow Press. pp. 129–. ISBN 978-0-8108-6061-2.

- ↑ Kamoludin Abdullaev; Shahram Akbarzaheh (27 April 2010). Historical Dictionary of Tajikistan. Scarecrow Press. pp. 381–. ISBN 978-0-8108-6061-2.

- ↑ Pannier, Bruce (April 1, 2015). "Central Asia's Controversial Fashion Statements". Radio Free Europe Radio Liberty.

- ↑ http://www.bbc.com/news/blogs-trending-36846249

- ↑ http://www.rferl.org/media/video/kyrgyzstan-islam-hijab-women/27888178.html

- ↑ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8QjZIRFi2n4&feature=youtu.be https://youtu. be/8QjZIRFi2n4 http://presskg.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/2-23.jpg

- ↑ http://sanat.orexca.com/2009/2009-4/binafsha_nodir-2/

- ↑ http://www.karakalpak. com/jegde.html

- ↑ http://sanat.orexca.com/2006/2006-3/national_costume/

- ↑ http://www.aquila-style.com/focus-points/asian-muslim-womens-fashions-of-the-past/8011/

- ↑ Northrop 2001, p. 198

- ↑ Hierman, Brent (January 20, 2016). "Citizenship in Soviet Uzbekistan". Dissertation Reviews.

- ↑ http://www.powerhousemuseum.com/collection/database/?irn=12271

- ↑ http://eurasia.travel/uzbekistan/cities/bukhara/history_of_bukhara/bokhara_-_the_forbidden_city/

- ↑ Craig Benjamin; Samuel N. C. Lieu (2002). Walls and Frontiers in Inner-Asian History: Proceedings from the Fourth Conference of the Australasian Society for Inner Asian Studies (A.S.I.A.S) : Macquarie University, November 18-19, 2000. Ancient History Documentary Research Centre, Macquarie University. ISBN 978-2-503-51326-3.

- ↑ Eliakim Littell; Robert S. Littell (1889). Littell's Living Age. T.H. Carter & Company. pp. 438–.The Living Age. Littell, Son and Company. 1889. pp. 438–.The Fortnightly Review. Chapman and Hall. 1889. pp. 130–.The Fortnightly. Chapman and Hall. 1889. pp. 130–.

- ↑ Ronald Grigor Suny; Terry Martin (29 November 2001). A State of Nations: Empire and Nation-Making in the Age of Lenin and Stalin. Oxford University Press. pp. 194–. ISBN 978-0-19-534935-1.

- ↑ Douglas Northrop (4 February 2016). Veiled Empire: Gender and Power in Stalinist Central Asia. Cornell University Press. pp. –. ISBN 978-1-5017-0296-9.Russia in Central Asia in 1889 & the Anglo-Russian Question. Longmans, Green, and Company. 1889. pp. 175–. https://archive.org/stream/russiaincentral00curzgoog/russiaincentral00curzgoog_djvu.txt http://cui-zy.com/Recommended/Nature&glabolization/SunyStalinA%20State%20of%20Nations.pdf https://www.scribd.com/document/233753278/Ronald-Grigor-Suny-Terry-Martin-a-State-of-Nati-BookZZ-org

- ↑ Ármin Vámbéry (1868). Sketches of Central Asia: Additional Chapters on My Travels, Adventures, and on the Ethnology of Central Asia. Wm. H. Allen & Company. pp. 170–171. https://archive.org/stream/sketchescentral00vmgoog/sketchescentral00vmgoog_djvu.txt

- ↑ Craig Benjamin; Samuel N. C. Lieu (2002). Walls and Frontiers in Inner-Asian History: Proceedings from the Fourth Conference of the Australasian Society for Inner Asian Studies (A.S.I.A.S) : Macquarie University, November 18-19, 2000. Ancient History Documentary Research Centre, Macquarie University. ISBN 978-2-503-51326-3.

- ↑ Januarius Aloysius MacGahan (1874). Campaigning on the Oxus, and the Fall of Khiva. Samps. Low. pp. 307–.

- ↑ j.a. mac gahan (1874). campaigning of the oxus and the fall of khiva. pp. 307–.

- ↑ Januarius Aloysius MacGahan (1874). Campaigning on the Oxus, and the Fall of Khiva. Samps. Low. pp. 307–. https://archive.org/details/campaigningonoxu00macg https://archive.org/details/campaigningonoxu01macg

- ↑ http://www.powerhousemuseum.com/collection/database/?irn=319780

- ↑ "Background: Women and Uzbek Nationhood". Human Rights Watch. Retrieved 16 September 2010.

- ↑ http://www.khiva.info/gb/clothes_earr/cl_of_past.htm

- ↑ http://www.aquila-style.com/focus-points/mightymuslimah/tamara-khanum/26863/

Further reading

- Northrop, Douglas (2001). "Nationalizing Backwardness: Gender, Empire, and Uzbek Identity". In Suny, Ronald Grigor; Martin, Terry. State of Nations: The Soviet State and Its Peoples. Oxford University Press. pp. 191–220. ISBN 978-1-234-56789-7.

- Northrop, Douglas (2003). Veiled Empire: Gender and Power in Stalinist Central Asia. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0801488917.

External links

For analysis of and discussion of the function of the robes, and for photos of such robes, see:

- Worldisround.com

- Powerhousemuseum.com

- http://www.all-about-photo.com/photographer.php?name=arkady-shaikhet&id=517&popupimage=8#top

- http://weheartit.com/entry/group/38110430

- http://www.susanmeller.com/books/silk-and-cotton/

- http://shop.hotmooncollection.com/uzbek-horsehair-face-veil/ https://www.pinterest.com/pin/101542166574656568

- http://www.talesoftheveils.info/dave_potter/new_uzbeki_woman.html