Paul von Hindenburg

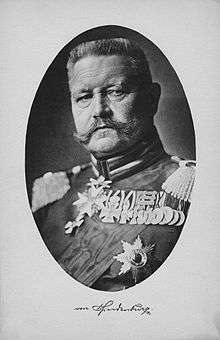

Paul Ludwig Hans Anton von Beneckendorff und von Hindenburg (![]() listen ), known generally as Paul von Hindenburg (German: [ˈpaʊl fɔn ˈhɪndn̩bʊɐ̯k]; 2 October 1847 – 2 August 1934) was a German military officer, statesman, and politician who served as the second President of Germany from 1925–34.

listen ), known generally as Paul von Hindenburg (German: [ˈpaʊl fɔn ˈhɪndn̩bʊɐ̯k]; 2 October 1847 – 2 August 1934) was a German military officer, statesman, and politician who served as the second President of Germany from 1925–34.

Hindenburg retired from the army for the first time in 1911, but was recalled shortly after the outbreak of World War I in 1914. He first came to national attention at the age of 66 as the victor of the decisive Battle of Tannenberg in August 1914. As Germany's Chief of the General Staff from August 1916, Hindenburg's reputation rose greatly in German public esteem. He and his deputy Erich Ludendorff then led Germany in a de facto military dictatorship throughout the remainder of the war, marginalizing German Emperor Wilhelm II as well as the German Reichstag. In line with Lebensraum ideology, he advocated sweeping annexations of territory in Poland, Ukraine, and Russia in order to resettle Germans there.

Hindenburg retired again in 1919, but returned to public life in 1925 to be elected the second President of Germany. In 1932, Hindenburg was persuaded to run for re-election as German president, although 84 years old and in poor health, as he was considered the only candidate who could defeat Adolf Hitler. Hindenburg was re-elected in a runoff. He was opposed to Hitler and was a major player in the increasing political instability in the Weimar Republic that ended with Hitler's rise to power. He dissolved the Reichstag (parliament) twice in 1932 and finally, under pressure, agreed to appoint Hitler Chancellor of Germany in January 1933. In February, he signed off on the Reichstag Fire Decree, which suspended various civil liberties, and in March he signed the Enabling Act of 1933, which gave Hitler's regime arbitrary powers. Hindenburg died the following year, after which Hitler declared the office of President vacant and made himself head of state.

Early years

Hindenburg was born in Posen, Prussia (Polish: Poznań; until 1793 and since 1919 part of Poland[1]), the son of Prussian aristocrat Robert von Beneckendorff und von Hindenburg (1816–1902) and his wife Luise Schwickart (1825–1893), the daughter of medical doctor Karl Ludwig Schwickart and his wife Julie Moennich. Hindenburg was embarrassed by his mother's non-aristocratic background and hardly mentioned her at all in his memoirs. His paternal lineage was considered highly distinguished; in fact, he was descended from one of the most respected ancient noble families in Prussia. His paternal grandfather was Otto Ludwig von Beneckendorff und von Hindenburg (1778–1855), through whom he was remotely descended from the illegitimate daughter of Count Heinrich VI of Waldeck. Hindenburg was also a descendant of Martin Luther and his wife Katharina von Bora through their daughter Margareta Luther. Hindenburg's younger brothers and sister were Otto (born 24 August 1849), Ida (born 19 December 1851) and Bernhard (born 17 January 1859). Hindenburg was proud that one of his ancestors, Colonel Otto Frederich von Hindenburg had lost a leg at the Battle of Torgau in 1760 and had been awarded an estate at Neudeck by Frederich the Great.[2] Like others of his generation, Hindenburg always saw himself first and foremost as a Prussian rather than a German, writing: "It does not matter to what part of our German Fatherland my profession has called me, I have always felt myself an ‘Old Prussian’".[3] Hindenburg received a typical Junker upbringing, being taught the virtues of duty, discipline, obedience to authority and loyalty to Prussia and piety towards the Lutheran Church.[4] Hindenburg was an intense militarist who was brought up to be a soldier by his parents, and for him war was something beautiful and romantic as he saw killing people to be the most noble and manly thing that a "real man" could do.[4] Hindenburg's governess was known to shout "Quiet in the ranks!" when the Hindenburg children were making too noise, and Hindenburg's best friend at the estate where he grew up was an elderly gardener who as a boy had served as a drummer in the Army of Frederich the Great, regaling the young Hindenburg with tales of Prussian military glory.[4] Before entering the Prussian Cadet Corps in 1859, the 12-year old Hindenburg soberly wrote up his last will and testament in case he should die, dividing up his toys amongst his siblings.[5] In a letter to his parents, the young Hindenburg wrote of his plans for a design in his room which would comprise:

"At the rear a big Prussian eagle on the wall; in the center, on an elevation, ‘Old Fritz’ [Frederick the Great] and his generals; at the foot of the elevation a number of Black Hussars; in front a chain with cannon posted behind it, more in the foreground and two watchman's booths, with two grenadiers of the time of Frederick the Great".[6]

The letter was typical of Hindenburg's correspondence with his parents were virtually everything he wrote concerned matters martial with civilian interests and pursuits mocked as matters for lesser beings.[6] Hindenburg's favorite reading materials were war and adventure stories with The Pathfinder by James Fenimore Cooper being his favorite.[7] As a cadet, Hindenburg was admired for his commitment to duty, obsession with details whose uniform was always immaculate with not even a single brass button left unpolished and his physical toughness while being considered of mediocre intelligence and utterly lacking in a sense of humor, a dedicated if somewhat dull cadet.[5]

German Army

After his education at cadet schools in Berlin and Wahlstatt (now Legnickie Pole), Hindenburg was commissioned as a lieutenant in 1866. He fought in the Austro-Prussian War of 1866 and the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–1871. During the Seven Weeks War of 1866, Hindenburg wrote his parents: "I rejoice in this bright-colored future. For the soldier war is the normal state of things…If I fall, it is the most honorable and beautiful death".[8] Hindenburg's helmet took an Austrian bullet, which he kept with him for the rest of his life as a lucky talisman.[8] During the war with France, Hindenburg fought at the bloody battle of St. Privat and was slightly wounded when a bullet from a French mitrailleuse (a primitive machine gun that was one of the more formidable of the French weapons) struck him in the leg.[9] Hindenburg credited the Prussian victory over the French at St. Privat as due to that "spiritual enthusiasm, a stern resolve to conquer and the holy lust of battle" that motivated the Prussians and commented dismissively that the French loved life too much and thus were afraid to die.[10] At St. Privat, Hindenburg's regiment lost 1, 005 dead or wounded, a source of great pleasure for Hindenburg who saw war as the most beautiful thing in the world with the corpses and shattered bodies of the wounded all part of what was for him the enchanting beauty of war.[11] During the Siege of Paris in 1870–71, Hindenburg did not share the common complaints by his fellow officers that the French were being stupid by refusing to surrender despite the fact it was clear that they had lost the war, instead expressing admiration for the French determination to uphold their honor and willingness to keep fighting in spite of the hopelessness of their situation.[12] A huge man standing at 6 feet 5 inches tall with a muscular frame and striking blue eyes who projected self-confidence and a sense of power, Hindenburg impressed everyone who met him.[13]

Hindenburg was selected for prestigious duties as a young officer. He served Elisabeth Ludovika, the widow of King Frederick William IV of Prussia, and was present in the Hall of Mirrors in the Palace of Versailles when the German Empire was proclaimed on 18 January 1871 as one of a group of officers decorated for bravery in battle who had been chosen to represent their regiments. In a letter to his parents, Hindenburg explained to them that he hated the French because the "French temperament is too vicarious and thus too capricious for my taste".[14] One of Hindenburg's proudest moments came when he took part in the victory parade in Paris as the soldiers of the Prussian and other German armies marched down the streets of Paris in triumph with pleased Hindenburg noting that the Parisians were all suitably humiliated by the experience.[14] Hindenburg loathed the French, but he expressed approval of the ruthless suppression of the Paris Commune by the French government in May 1871, which he described as an act of necessary violence to uphold the social order, views that prefigured Hindenburg's actions in January 1919 when he unleashed the Freikorps' to crush the Spartakusbund in Berlin with orders to take no prisoners.[12] Hindenburg also served as an Honour Guard prior to the Military funeral of Emperor William I in 1888. At the funeral of Wilhelm I, Hindenburg took a piece of gray marble from the cathedral floor and always had it with him for the rest of his life to remind him of "my king".[15] He was promoted to captain in 1878, major in 1881, lieutenant-colonel in 1891, colonel in 1893, major-general in 1897 and lieutenant general in 1900.[16] Hindenburg eventually commanded a corps and was promoted to the rank of General of the Infantry in 1903. Meanwhile, he married Gertrud von Sperling (1860–1921), also an aristocrat, by whom he had two daughters, Irmengard Pauline (1880) and Annemaria (1891), and one son, Oskar (1883).

As the commander of the Ninety-first Infantry Regiment, which he took command of in 1893, Hindenburg worked in his words "to cultivate a sense of chivalry among my officers and efficiency and firm discipline as well the love of work and independence side by side with a high ideal of service".[15] As an officer, Hindenburg was noted for his self assurance, his ability to keep his cool, his care of his men, a gruff sort of charm and for being a very committed through unimaginative commander.[17] In 1908 during one of the Kaisermanöver (Emperor's Maneuvers) as war games commanded by the Emperor Wilhelm II were known, Hindenburg commanding the 4th Army Corps broke the most important of the unwritten rules governing the war games by defeating the Kaiser, a "victory" that did not endear him to the Supreme Warlord who blocked him from being appointed to the General Staff.[17] In January 1911, Hindenburg retired and devoted his time to hunting, his favorite pastime, and despite being a Lutheran collecting Madonna and chid figurines.[18] Hindenburg ascribed to xenophobic and militarist views, seeing the Reich as being "encircled" by enemies, and thought that war was the best solution to all international problems.[19] Like many other Prussian officers, Hindenburg favored deciding wars via a few battles of annihilation with the Geist or spirit deciding the outcome of wars.[20] Recalling the war with France, Hindenburg always noted that the French had superior weapons, but the Germans had superior willpower, and it was the latter that always decided the outcome of wars.[21] During the course of his life, Hindenburg's military duties took him to the Russian Empire, France, Belgium, Austria and he once took a trip to Italy; otherwise, Hindenburg spent his entire life within Germany as he had no interest in the world outside of Germany saying that Ausland ("outland", i.e. abroad) was irrelevant to him.[20] Hindenburg's interests were entirely military and he had almost no understanding of economics or the world of business.[22] Likewise, Hindenburg understood war at the tactical and operational level, and had little interest in strategy or grand strategy, responding to difficult strategical questions by focusing on improving tactics and fostering the will to win.[20]

World War I

Hindenburg retired from the army for the first time in 1911, but was recalled in 1914, shortly after the outbreak of World War I, by Helmuth von Moltke, the Chief of the German General Staff. In August 1914, Russia had mobilized much more quickly than the German General Staff had expected, and two Russian armies entered East Prussia, leading to panic on the German side.[23] Moltke the Younger decided that the man to save the situation was Erich Ludendorff, a man considered brilliant, but emotionally and mentally unstable who was known to fall to pieces when things did not work out as planned and who suffered the further handicap of being from a middle-class family in an officer corps dominated by Junkers.[24] To resolve this problem, Moltke decided to make Ludendorff the chief of staff to Hindenburg, a Junker known for his calmness in a crisis.[24] Hindenburg was swiftly called out of retirement and reported to duty wearing an improvised uniform consisting of civilian black trousers and a Prussian blue tunic he borrowed from a relative of his wife.[25] As Hindenburg left his train station in Hanover, he had been very impressed with the patriotic frenzy of the "Spirit of 1914", writing to his son-in-law: "How glorious is the bearing of our people!".[26] Hindenburg was given command of the Eighth Army, then locked in combat with two Russian armies in East Prussia. Hindenburg's predecessor Maximilian von Prittwitz had been planning to abandon East Prussia and retreat behind the River Vistula after suffering defeat by the Russian First Army at the Battle of Gumbinnen.

Nonetheless, Hindenburg's Eighth Army was soon victorious at the Battle of Tannenberg and the Battle of the Masurian Lakes against the Russian armies. Hindenburg and Ludendorff had a "marriage" of minds with the older and calmer Hindenburg providing much needed stability and support to the more intelligent Ludendorff who was however of questionable mental stability even at the best of times.[27] Upon arriving at the HQ of the 8th Army, Hindenburg impressed everyone with his refusal to panic, and his insistence that the Russians could be beaten provided that everyone just stay calm.[27] Most of the planning was done by Ludendorff and Max Hoffmann, who took advantage of the fact that the Russians were sending their radio messages "in the clear" (i.e. uncoded) and the separation between the Russian 1st Army and the 2nd Army to bring five German corps to encircle the Russian 2nd Army.[28] Historians such as G. J. Meyer attach much of the credit to Erich Ludendorff and to the little-known staff officer Max Hoffmann, but these successes made Hindenburg a national hero.[29] The victory at Tannenberg resulted in the destruction of the Russian 2nd Army with 92, 000 Russians captured together with four hundred guns.[30] Hindenburg suggested giving the name of the battle "Tannenberg" as a way of "avenging" the defeat inflicted on the Order of the Teutonic Knights by the Polish and Lithuanian knights in 1410 even through the battle was fought nowhere near the field of Tannenberg.[31] In 1914, the battle of Tannenberg was presented by the German newspapers in mythical and mystical terms as part of a "race war" between the Germanic and Slavic peoples, a battle that transcended the immediate issues of 1914 to become part of something larger and more mysterious with Hindenburg as the defender and avenger of Deutschtum against the Slavs.[31]

Hindenburg was awarded the Pour le Mérite or the "Blue Max", Prussia's highest decoration for bravery for Tannenberg.[31] Hindenburg's massive frame and his firm, gruff yet grandfatherly persona made him into Germany's most popular man.[31] Unlike the Kaiser who largely disappeared from public life after the war started, spending his time in seclusion at his palaces and hunting lodgings, Hindenburg was glad to at the center of the public limelight.[32] All over Germany, wooden statues of Hindenburg known as Nagelsäulen were erected and it became a popular way to raise money for the war effort at public rallies where people would nail marks into the Nagelsäulen.[33] The public adoration went to Hindenburg's head and soon his ego grew to colossal proportions.[34] On 4 September 1914 Hindenburg modestly wrote to his daughter saying it was God that won the Battle of Tannenberg, not him, but by the beginning of October 1914 Hindenburg had changed his mind about who won Tannenberg, saying it was all his work.[35] In October 1914, Hindenburg wrote to his daughter: "Here things are quite good. It may sound arrogant but it is so: since my arrival there has been a great turn-around in this theater of the war".[36]

In August 1914, Wilhlem II had what Astore and Showalter called his "one shining moment" during his thirty-year reign when he announced before the Reichstag the Burgfrieden ("peace within a castle under siege") as henceforth to face the challenge of the war all of the differences between rich, middle class, and poor; Protestants and Roman Catholics; urban and rural; left and right and between all of the Staaten (states) of the Reich were now meaningless and the German people were one.[37] Even the Social Democrats who were nominally pacifists broke into two with the Majority Social Democrats rallying to the Fatherland as they believed their government's claim that Russia was supposedly about to invade Germany, thus necessitating a "preventive war", and only a minority in the form of the Independent Social Democrats held true to their pacifistic principles. With the exception of the Independent Social Democrats, all of the German political parties supported the war, and the Burgfrieden proved remarkably effective in creating a national consensus in favor of the war.[37] Hindenburg had been very impressed at the way that the Spirit of 1914 had fused the formerly factious German nation into one and like many other Germans wanted to convert the wartime Burgfrieden into a peacetime Volksgemeinschaft (people's community) that would keep the nation united forever.[38] Before 1914, German society had been bitterly divided between Catholics vs. Protestants; the rising power of the SPD and the unions against the government and business; between those who lived in the cities vs. those who lived in the countryside; between those favored traditional culture vs. a modernist new culture; and for someone like Hindenburg to see all these divisions dissolve as much of the nation was caught up in the "Spirit of 1914" was a deeply reassuring portent of what the future could be like.[39] Hindenburg came to see creating Volksgemeinschaft as his life's mission as he viewed himself as the nation's guardian, writing: "May we never lose the spirit of 1914."[26]

Just as important as deciding the fate of the Eastern Front were the battles in Galicia in August and September 1914, where the Russians destroyed much of the Austrian Army and occupied much of Galicia.[40] With the possibility that Austria-Hungary might be knocked out of the war altogether becoming more and more real by the day, Hindenburg and Ludendorff in October 1914 started an offensive into Russian Poland with the aim of taking Warsaw.[41] In the face of fierce Russian resistance, Hindenburg had to break off his offensive, but he did succeed in reliving pressure on the Austrians.[42] On 1 November 1914, Hindenburg was given the position of Supreme Commander East (Ober-Ost), although at this stage his authority only extended over the German portion of the front, not the Austro-Hungarian, and units were transferred from East Prussia to form a new Ninth Army in southwestern Poland. Hindenburg detested his Austrian allies, writing that the entire leadership of the Habsburg Army was "incompetent" and constantly complained supporting Austria was a major drain on the German war effort while Franz Conrad von Hotzendorf of the Austrian General Staff charged that his German allies were the overbearing and arrogant "secret enemy" of Austria.[40] Hindenburg renewed his offensive with the aim of taking Łódź, which was initially successful, but was soon stopped by the Russians who threatened to encircle the advancing Germans.[43] The climax of the Battle of Łódź was the escape of General Reinhard von Scheffer-Boyadel's 25th Corps from an attempt by the Russians to encircle and annihilate it.[43] On 27 November 1914, after the Battle of Lodz, Hindenburg was promoted to the rank of Generalfeldmarschall ("General Field Marshal"), the highest rank in the Prussian Army.[43] A field marshal's baton was a symbol of great prestige in Germany, and henceforth Hindenburg was rarely seen in public, photographs, and paintings without his field marshal's baton.[43] A further battle was fought by the Eighth and newly formed Tenth Armies in Masuria that winter. Ober-Ost eventually consisted of the German Eighth, Ninth, and Tenth Armies, plus other assorted corps.

Hindenburg and Ludendorff felt that more effort should be made on the Eastern Front to relieve the forces of Germany's ally, the Ottoman Empire, in order to defeat Russia. By contrast, Erich von Falkenhayn, the Chief of the General Staff, felt that it was impossible for Germany to win a decisive victory in this way. Hindenburg feuded constantly with Falkenhayn, who favored focusing on defeating France rather Russia, a strategy Hindenburg was opposed to.[44] Falkenhayn felt that building up forces in the east could not lead to victory in an overall conflict involving two fronts. Indeed, he hoped that Russia might be encouraged to drop out of the war if not pressed too hard. Annoyed at the open insubordination of Hindenburg and Ludendorff, Falkenhayn tried to break up the duo by giving Ludendorff command of a new army, which led Hindenburg to write a letter to the Kaiser asking him to sack Falkenhayn while at the same time enlisting the Crown Prince Wilhelm to pressure his father not to break up the Hindenburg-Ludendorff partnership.[45] Feeling intimidated by the menacing Hindenburg and knowing the German public would not accept his sacking, Wilhelm II chose not to stand by Falkenhayn and gave in to Hindenburg, reassigning Ludendorff to Hindenburg yet retaining Falkenhayn as Chief of the General Staff.[45] This crisis in command did much to diminish Falkenhayn's authority as he had proved incapable of asserting his authority over Hindenburg.[45] The German historian Wolfram Pyta described Hindenburg's authority as corresponding to Max Weber's category of Charismatic authority as Hindenburg's power rested not on any of the offices he held, but rather on his personage and his status as a symbol of all that good and great in Germany, a "constantly renewable popular consensus that extended to all sectors of German society and that bound the German people to his person and the project of national unity that become synonymous with his person".[46]

At the Second Battle of the Masurian Lakes in early 1915, Hindenburg defeated a second Russian invasion of East Prussia, destroying the Russian 10th Army and taking 55, 000 Russians prisoners.[45] The American former Republican Senator Albert J. Beveridge interviewed Hindenburg in February 1915.[47] Beveridge wrote he was impressed with Hindenburg, calling him: "broad-shouldered, thick-chested…the immense stature, the huge frame, the impression of tremendous, steady, unyielding force. Here is a man who makes up his mind about what he wants or wants to do, and then has no further doubt on the subject. It is the kind of self-confidence that inspires confidence in others".[47] When Beveridge asked Hindenburg who was responsible for the war, Hindenburg blamed Britain, which he claimed had become jealous of German economic success and incited Russia to mobilize in July 1914, thus "forcing" Germany to defend itself.[47] Hindenburg claimed that France was likewise under British incitement planning on attacking Germany in conjunction with Russia and was going to violate Belgian neutrality, which thus "justified" Germany invading neutral Belgium as part of its alleged defensive "preventative war".[47] When Beveridge told Hindenburg that he thought that the Reich was a deeply militarist country with many German conscripts fighting "the Kaiser's war" against their wills, a furious Hindenburg replied: "The German Army is the German people! The German Emperor and the German people are one!".[47] Hindenburg explained to Bevridge that his nation would win the war because:

"Our knowledge that we are right; the faith of the nation that we shall win; their willingness to die in order to win; the perfect discipline of our troops; their understanding of orders; their greater intelligence, education and spirit; our organization and resources".[48]

For the spring of 1915, Hindenburg and Ludendorff proposed a huge offensive into Russian Poland with eight corps which together with an Austrian offensive from Galicia would take Warsaw in an enormous Kesselschlacht (cauldron battle) that would "annihilate" the Imperial Russian Army forces in Congress Poland with the aim of knocking Russia out of the war.[49] Falkenhayn vetoed this plan as too ambitious, but a modified and scaled down version of this plan was launched in May 1915.[49] Hindenburg's offensive into Russian Poland led to the Russians suffering about 300,00 casualties with Hindenburg taking Warsaw on 4 August 1915 and Vilna on 18 September 1915.[49] However, Hindenburg failed to achieve his decisive battle of annihilation that would force Russia to sue for peace in 1915.[50] Much to Hindenburg's fury, the Kaiser snubbed him at the awards ceremony when Wilhelm refused to allow him to ride in his car, giving that honor to General Hans von Beseler (though the Kaiser did award Hindenburg the Pour de Mérite with Oak Leaves).[50] Wilhelm II was immensely jealous of the fact that Hindenburg was far more popular with the German people then he was at this time of crisis, and often feared that Hindenburg would become "the people's tribunal" who would try to set up a populist, right-wing military dictatorship that would marginalize him.[51] The German command system was not characterized by unity, instead being a nest of intrigue with the Germany unable to agree to a common strategy with Austria, the military plotting to sideline Wilhelm whom they regarded as an ineffective war leader, the General Staff scheming against the War Ministry, the Army competing with the Navy, and Hindenburg and Ludendorff making no secret of their wish to oust Falkenhayen.[52] Instead of pursuing an eastern strategy, Falkenhayn unleashed an offensive at Verdun in 1916 in order to "bleed France white"[53] and encourage her to make peace. For his part, Hindenburg was anxious to conquer the Baltic region from the Russian Empire. He recognized the strategic value of controlling its territories in the event of another war with Russia, and he also wished to see it colonized by ethnic Germans.[54]

Hindenburg's own military ability is disputed,[55] but he had a team of talented and able subordinates who won him a series of great victories on the Eastern Front between 1914 and 1916. These victories transformed Hindenburg into Germany's most popular man.[56] Despite his reputation as Germany's greatest commander, Hindenburg did not play a very active role in command, spending most of his time posting for photographs and paintings (Hindenburg had an ego equal to his girth), walking, hunting, and eating his favorite meals of bottled eels, rusk (a type of sweet biscuit) and a pyramid cake and drinking brandy and champagne.[57] Hindenburg especially liked to kill stags, the symbol of the Hindenburg family that was prominently marked on the Hindenburg family crest.[57] Hindenburg's staff who did most of the work were often annoyed at the way in which the egomaniac Hindenburg always took all the credit for their work.[57] Hoffmann complained in September 1915: "We generally sign the orders 'von Hindenburg' without having shown them to him at all. The most brilliant commander of all times no longer has the slightest interest in military matters; Ludendorff does everything himself".[57] Hindenburg generally kept himself informed of the broad picture and was content to let his staff work out the details, being more concerned with his image.[58]

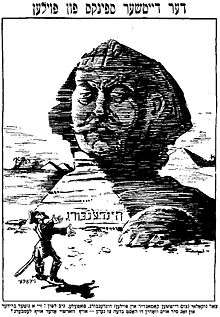

During the war, Hindenburg was the subject of an enormous personality cult. He was seen as the perfect embodiment of German manly honour, rectitude, decency, and strength, the "savior of the fatherland".[59] Typical of the wartime writing about the Field Marshal were the statements of Hindenburg's niece, Nostiz von Hindenburg who wrote of her uncle: "One might compare Hindenburg to one of those big firmly-rooted oaks of the Prussian landscape under whose shade so many find protection and rest. He seemed to rise out of an old legend of our forefathers. He incorporated the soul of our nation, without being in the least self-conscious of it. And one felt awed at its tragic presence".[60] In the words of the American historians William Astore and Denis Showalter, Hindenburg embodied "mature masculinity" to German men while to German women he was a both a "loving husband and father", the man who never let them down and always looked after them.[60] The appeal of the Hindenburg cult cut across ideological, religious, class, and regional lines, but the group that idolized Hindenburg the most was the German right, who saw him as an ideal representative of the Prussian ethos and of Lutheran, Junker values.[60] During the war, there were wooden statues of Hindenburg built all over Germany, onto which people nailed money and cheques for war bonds, which become one of the most effective ways of raising money for the war.[61] During the war, Hindenburg was so popular that he become a symbol of Germany itself.[61] When Germans who were annexationists spoke of what they wanted after the war, it was always a "Hindenburg peace", meaning a peace with extensive conquests in Europe, Africa and Asia.[61] Hindenburg's popularity was such was his Abendtrunck or evening drink of a glass of water with a bit of lemon and sugar become the national rage.[61] All over Germany during the war, one could buy countless Hindenburg beer mugs, pipes, coins, china, postcards and posters.[62] Restaurants and beerhalls had dishes and drinks named after him, and the popular ritual of nailing money to the Nagelsäulen become a fetishistic expression of national pride and the will to win.[61] The largest of the Nagelsäulen was a twenty-eight ton statue raised in the Köeingsplatz in Berlin in August 1915 that was the object of a weekly fund raising drive with thousands of ordinary people competing to see who would nail the most marks of the highest value into it.[33] During the war, several books were published of Hindenburg's table talks, which despite being mostly banal and boring were all bestsellers as the German people could never get enough of what was perceived as Hindenburg's wit and wisdom.[33] Every day, Hindenburg received several large bags of letters and gifts from ordinary Germans thanking him for his victories, and he had to create a special office within his command just to handle the fan mail.[62] It was a measure of Hindenburg's public appeal that, when the Government launched an all-out programme of industrial mobilisation in 1916, it was named the Hindenburg Programme rather the Kaiser Wilhelm Programme.[56]

By the summer of 1916, Erich von Falkenhayn had been discredited by the disappointing progress of the Verdun Offensive and the near collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Army caused by the Brusilov Offensive and the entry of Romania into the war on the Allied side. The summer of 1916 was a period of crisis for Germany.[63] The Battle of Verdun was leading to Germany suffering huge casualties, in June 1916 the Russians launched the Brusilov Offensive that took much of Galicia and Bukovinia, in July 1916 the British launched the Battle of the Somme and in August Romania entered the war on the Allied side.[64] All over Germany, newspapers demanded that Falkenhayn be sacked and replaced with Hindenburg.[65] The Chancellor, Dr. Bethmann Hollweg wrote to General Baron Moritiz von Lyncker on 23 June 1916: "The name Hindenburg frightens our enemies, galvanizes our army and people, which have boundless confidence in him...If we were to lose a battle, which God forbid, our people would nevertheless accept it, and likewise any peace to which he would put his name".[66] In July 1916, Falkenhayn challenged Hindenburg about his desire to replace him as chief of the general staff, saying: "Well, if Herr Field Marshal has the desire and courage to take the post", only to be interrupted by Hindenburg who said "The desire, no, but the courage-yes".[66] With tears in his eyes, Wilhelm appointed Hindenburg chief of the general staff.[66] In August 1916, Hindenburg succeeded Falkenhayn as Chief of the General Staff, although real power was exercised by his deputy Erich Ludendorff.[67] Hindenburg in many ways served as the real commander-in-chief of the German armed forces instead of the emperor, who had been reduced to a mere figurehead, while Ludendorff served as the de facto general chief of staff. The Kaiser had become a mere Schattenkaiser (shadow emperor) a reclusive, rarely seen leader who was almost completely ignored in the popular adulation of Hindenburg, who for most Germans saw as the personification of the nation and whom Hindenburg ordered about in private.[68] From 1916 onwards, Germany became an unofficial military dictatorship, often called the "Silent dictatorship"[56][69] by historians. Hindenburg was a monarchist by inclination, but his monarchism was of a type peculiar to officer corps, which viewed the monarchy as the best form of government, but at same time German officers' first loyalty was to the institution of the army rather than the monarch.[70] King Frederich Wilhelm III of Prussia had been such an inept monarch that after Prussia's crushing defeat by the French in 1806-07 that the military had undertaken the task of reform themselves rather wait for their dithering king, which was the origin of the military "state within the state" in Prussia. As such, Hindenburg did not hesitate to break his oath of loyalty to Wilhelm II by taking decisions that properly were the Kaiser's to make under the grounds just as in the Napoleonic wars the military had both the right and duty to usurp tasks that constitutionally speaking were the prerogative of the monarch.[71]

The news of Hindenburg's appointment was well received by the German people.[72] One German soldier, Karl Gorzel serving on the Western Front wrote in October 1916: "As we were passing through Cambrai, we saw Hindenburg and greeted him with exultant cheers. The sight of him ran through our limbs like fire and filled us with boundless courage".[72] In September–October 1916, Hindenburg and Ludendorff visited the Western Front for the first time.[72] After seeing the battlefields of Verdun and the Somme, a shocked Hindenburg wrote that frontline soldiers "hardly ever saw anything but trenches and shell holes…for weeks and even months…I could now understand how everyone, officers and men alike, longed to get away from such an atmosphere".[73] In response, Hindenburg concluded that his previous emphasis on the will to win, the idea of war as a spiritual struggle with the side with the stronger will prevailing had to be modified somewhat as the war had become a Materialschlacht ("material battle"), a total war in both sides sought to mobilize their entire societies in support of the war.[73] Hindenburg was an annexationist, someone who believed that the war should end with the Reich annexing much of Europe, Africa and Asia to make Germany into the world's greatest power.[74] As such, Hindenburg's policies ruled out any possibility of compromise peace as only by defeating Britain, France and Russia could give Germany the victory that Hindenburg envisioned and thus required that Germany achieve a "total victory" over her enemies.[75] Hindenburg wanted as a minimum to annex Belgium, most of northern France and much of the Russian Empire, plus many of the British and French colonies in Africa and Asia.[76]

Reflecting this policy choice to go for total victory was the Hindenburg Programme by having the state take over the economy to create a total war economy, a policy known as "war socialism".[77] Neither Hindenburg or Ludendorff had much understanding of economics, and in the words of Astore and Showalter their "key mistake was to presume that an economy could be commanded like an army. What was best for the army in the short term was not necessarily best for the long-term health of the economy…Extreme economic mobilization encouraged grandiose political and territorial demands, ruling out opportunities for a compromise peace, which Hindenburg and Ludendorff rejected anyway. Under their leadership, Imperial Germany became a machine for waging war and little else…As enacted, the Hindenburg Programme sought to maximize war-related production by transforming Germany into a garrison state with a command economy. Coordinating the massive effort was the Kriegsamt, or War Office, head by General Wilhlem Groener".[77] As Hindenburg did not know much about business or economics, much of the work of the Hindenburg Programme was actually done by Ludendorff and his aide, an officer of extreme right-wing views, Colonel Max Bauer who began a crash program of economic centralization whose "unachievable production goals led to serious dislocations in the national economy. Shell production was to be doubled, artillery and machine gun production trebled, all in a matter of months. The German economy, relying largely on its own internal resources, could not bear the strain of striving for production goals unconstrained by economic, material and manpower realities".[78]

Furthermore, to achieve the impossible targets set out by the Hindenburg Programme, the German state restored to conscripting Belgian workers to Germany, which proved to be a public relations disaster that alienated opinion in the neutral United States.[78] Furthermore, within Germany, the emphasis on the Hindenburg Programme upon industrial production at all costs led to major food shortages and caused the Kohlrübenwinter (turnip winter) of 1916–17 was most Germans were forced to eat tulip derivatives to avoid starving to death, through Hindenburg was successful in persuading the German people that it was the British blockade instead of his policies that had caused the "Hunger Winter".[79] By early 1917, Germans were eating only a fifth of the meat and butter consumption levels of 1914 with turnip and other ersatz foods providing most of the daily substance.[80] In December 1916, the duumvirate of Hindenburg and Ludendorff had the Reichstag pass the Hilfsdienstgesetz (Patriotic Auxiliary Service Law) which imposed national service on all men from ages 17 to 60 and imposed drastic restrictions on the right of German workers to change jobs.[80] Some easing of the German economic problems occurred in December 1916, when Field Marshal August von Mackensen conquered much of Romania.[81] Romania, which is rich in oil and has some of the most fertile farmland in Europe proved to be a most valuable conquest for Germany.[82]

Hindenburg had been very critical of Falkenhayn's leadership, but taking command of the Reich, he was initially at a loss about how to win the war.[83] Ever since the summer of 1916, the German Navy with the retired, but still very popular Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz as its chief spokesman had been insisting that if Germany could conduct unrestricted submarine warfare, then within six months the U-boats would sink enough shipping to stave Britain into surrender.[84] Britain's population considerably exceeded its agricultural capacity and without food imported from abroad a famine would ensure in the United Kingdom. If the U-boats could sink enough British shipping to ensure that famine broke out in Britain, then the British would have to sue for peace om German terms, and with Britain knocked out of the war, then France and Russia would also have to likewise make peace on German terms. Hindenburg and Ludendorff with their commitment to total victory had decided in January 1917 to go for broke and ordered the resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare, taking the gamble that a "naval guerre à outrance" would starve Britain into submission, even though they both knew that such a step would almost certainly bring the United States into the war.[85] At a meeting with the Kaiser in February 1917, the physicist Walther Nernst told the Kaiser that the American President Woodrow Wilson had often said ever since the sinking of the Lusitania in 1915 and the Sussex in 1916 that the United States would enter the war if Germany resumed unrestricted submarine warfare, and advised Wilhelm to stop the U-boat offensive before it was too late.[86] With Hindenburg nodding in approval, Ludendorff contemptuously commented that Nernst's warnings were "the incompetent nonsense of a civilian".[67] As the diplomatic counterpart to the gamble on unrestricted submarine warfare, Hindenburg and Ludendorff had the Zimmermann telegram issued in February 1917 proposing an anti-American alliance with Mexico and Japan; argued for Mexico invading the United States; promising the Mexicans they could have back the American states of California, Arizona, New Mexico, Nevada, Utah, Colorado, and Texas once Germany defeated the United States; and suggested that the Mexicans pass along a message to Tokyo proposing that the Japanese switch sides.[87] The Zimmermann telegram was intercepted by the British, whose codebreakers in Room 40 had broken the German diplomatic codes, who then leaked the telegram to the American press with fabricated story that MI6 had stolen the Zimmermann telegraph after a break-in at the German embassy in Mexico City.[88] The Zimmermann telegraph enraged American public opinion and thus ensured the United States would enter the war as the majority of the American people were incensed that Germany was attempting to incite Mexico to invade America.[88] The gambit on U-boats failed with the British adopting the convoy tactics to defeat the U-boats who did not sink enough shipping to stave Britain into surrender while the Zimmerman telegraph and the sinking of American ships caused the United States to declare war on Germany in April 1917.

In the meantime, Hindenburg and Ludendorff decided to on a defensive strategy for the Western Front in 1917 while pursuing an offensive strategy on the Eastern Front with aim of finally defeating Russia.[81] Starting in February 1917, the German forces withdraw back to an elaborate defense-in-depth line known to the Germans as the Siegfried Line and to the Allies as the Hindenburg Line.[89] By this time, Hindenburg had become known as the ersatzkaiser (substitute emperor) as he was far more popular than the real Kaiser.[90] As the Reichstag which was dominated by the Majority Social Democrats and the Zentrum sought to block Hindenburg's annexationist plans for victory by passing a peace resolution, Hindenburg decided to exercise his political power by having the Chancellor Dr. Bethmann Hollweg sacked.[90] On 27 June 1917, Hindenburg told Wilhelm to fire Bethmann Hollweg, saying the Chancellor was responsible for "the decline in national spirit. It must be revived or we shall lose the war".[88] Ludendorff followed up by saying Bethmann Hollweg was the man aiding "German Radical Social Democracy and its longing for peace".[90] On 13 July 1917, Bethmann Hollweg was fired as Chancellor under strong pressure from Hindenburg and Ludendorff, and replaced with Georg Michaelis, a weak-willed man whom Bauer called the "chancellor of the OHL" as he was completely under the thumb of Hindenburg and Ludendorff.[91] The sacking of Bethmann Hollweg was an extremely bitter blow to Wilhelm, who had wanted to keep him on as Chancellor.[92] Writing in third person, a despondent Wilhelm declared: "It is high time for him to abdicate since for the first time a Prussian monarch had been forced by his generals to do something that he didn't want to do", going on to complain that Hindenburg had just "castrated" him by stripping him of all his power, leaving him as a mere figurehead.[93] The two warlords followed up their triumph in September 1917 by having the Fatherland Party headed by Wolfgang Kapp and Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz founded with the aim of mobilizing public support for their annexationist war aims.[75] In the same vein, Hindenburg and Ludendorff began a programme of Vaterländischer Unterricht (patriotic instruction), a systematic propaganda campaign in the media designed to win the public over to their annexationist policies while distorting the war completely by never mentioning any defeats and underreporting casualties.[94]

What had sustained the Burgfrieden was the almost universal belief in the Reich that Germany was the victim of Allied aggression, and as long as the war was presented in defensive terms, the Burgfrieden held.[37] With Hindenburg and Ludendorff becoming increasingly open in expressing their annexationist war aims, the Burgfrieden began to break down in 1917 as many Majority Social Democrats, the Progressives and the Zenturm started to make clear that they were opposed to a war of conquest.[37] On 19 July 1917, the Zentrum, the Majority Social Democrats, the Progressives and Independent Social Democrats all joined forces to vote the Reichstag Peace Resolution asking the government to make peace with the Allies at once on the basis of no annexations, a resolution that both Hindenburg and Ludendorff regarded as an act of high treason. In 1917, it started to dawn on many Germans that they government had lied to them about the reasons the outbreak of the war in 1914, and that far being a defensive struggle the war was in fact a war of conquest.[37] It was at this point that Hindenburg started to cease being a figure who transcended ideological lines to be a national figure and rather became a more partisan, sectarian figure, a man of the Prussian right whom the Zentrum, liberals and leftists saw as dragging out the war to achieve annexationist war aims they were opposed to.[37] Moreover, the economic sacrifices demanded by the Hindenburg Programme were borne mostly by the poor and working class Germans who began to grumble that the Junkers were not being asked to suffer the same sort of drastic reduction in living standards that they were.[94] A popular joke in 1917 Germany was the acronym k.v meaning "fit for front-line service" actually stood for keine Verbindung ("little [political] pull"), the acronym g.v meaning fit for garrison service really stood for gute Verbindung ("good pull") and the acronym a.v for fit for home service really meant ausgezeicchnete Verbindung ("excellent pull").[94] It was at this time that the first cracks started to appear in the Hindenburg cult.[94]

On 2 October 1917 saw the height of the Hindenburg cult as his 70th birthday was celebrated lavishly all over Germany, being made a public holiday, an honor that until then had been reserved only for the Kaiser.[95] Hindenburg published a birthday manifesto, which somehow managed to claim at one and the same time that Germany had fighting a defensive war imposed by the Allies while at same time claiming that the Reich was fighting to gain Lebensraum (living space) to provide for "free growth".[96] Hindenburg's birthday manifesto ended with the words:

"With God's help our German strength has withstood the tremendous attack of our enemies, because we were one, because each gave his all gladly. So it must stay to the end. ‘Now thank we all our God’ on the bloody battlefield! Take no thought for what is to be after the war! This only brings despondency into our ranks and strengthens the hopes of the enemy. Trust that Germany will achieve what she needs to stand there safe for all time, trust that the German oak will be given air and light for its free growth. Muscles tensed, nerves steeled, eyes front! We see before us the aim: Germany honored, free and great! God will be with us to the end!"[97]

Russia's collapse later that same year with the new government led by Vladimir Lenin signing an armistice later that year seemed to confirm Hindenburg's birthday message.[94] On 11 November 1917, at a secret conference held in Mons, Ludendorff announced that in the spring of 1918 Germany would launch a major offensive on the Western Front codenamed Operation Michael that would win the war.[98]

When the Chancellor Georg von Hertling suggested that Germany might be moderate in peace terms with Russia, Hindenburg in a letter to the Kaiser on 7 January 1918 wrote: "Your Majesty, we will not order honest men who have served Your Majesty and the Fatherland faithfully to attach the weight of their names and authority to proceedings which their innermost conviction tells them to be harmful to the Crown and the Reich".[68] Hindenburg went on to claim that the morale of the soldiers about to embark on Operation Michael would be badly damaged if the Reich did not impose the most onerous peace terms on Russia as only sweeping territorial gains in the East could justify sacrifices in the West, an argument which put an end to any possibility of a moderate peace with Russia.[94] A pleased Hindenburg told Ludendorff two days later that the peace treaty with Soviet Russia was going to be a "conqueror's peace".[94] On 16 January 1918, Hindenburg scored another triumph by forcing Wilhelm to dismiss Rudolf von Valentini, the chief of his secret privy council under the grounds that ultra-conservative Valentini was a "left-wing" influence on the Kaiser that needed to go and an "enemy in the rear" that was hindering his work.[99] Hindenburg further told Wilhelm that he was to sever his friendship with Valentini and never see or hear from him again, an unprecedented act of effrontery as never before had a Prussian field marshal dared to dictate to his monarch about who could be his friend.[100] By this point, Hindenburg could have deposed Wilhelm to found a new regime if he been willing, but he chose to allow Wilhelm to reign on for sentimental reasons as Hindenburg had a personal preference for monarchies over republics.[101]

Contrary to what Hindenburg was claiming about popular support for a "conqueror's peace", in January 1918 a strike wave broke out in the munitions industry with over a million workers laying down their tools with the strike leaders calling for a better living conditions than those imposed by the Hindenburg Programme; democratization of the political system; and a rejection of annexationist war aims, a sign that much of the German public did not share Hindenburg's annexationist war goals or was willing to suffer much longer to achieve them.[102] At a meeting of the German Crown Council in February 1918 to discuss what peace terms to seek with the Russians, the Kaiser wanted to partition Russia, Hindenburg stated that he need to annex all of the Baltic states while Ludendorff suggested the Reich should annex all of Russia up to the Caspian Sea.[103] A recurring theme of Ludendorff and Hindenburg's remarks on Eastern Europe and Russia in particular was the emphasis upon the East as a source of power, a "land of limitless possibilities" that was just waiting to be exploited by Germany.[98] Reflecting that their role as much political as military, in the winter of 1918, Ludendorff and Hindenburg were deeply involved in negotiating a peace treaty with Romania, even at the expense of planning for Operation Michael.[104] Hindenburg and Ludendorff clashed openly with the foreign state secretary Richard von Kühlmann who wanted to place Romania into the German sphere of influence indirectly as opposed to the more naked imperialism of the duumvirate who saw Romania as variously as "our Canada", "our India" or "our Egypt", a land rich in natural resources like oil that was going to be exploited for Germany's benefit.[105] Hindenburg and Ludendorff used the Pan-German League to attack Kühlmann's handling of the negotiations, leading the British historian Martin Kitchen to write that "...demagogic appeals to popular support from the ultra-right were characteristic of the politics of Hindenburg and Ludendorff.[104]

In March 1918, the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk was signed between Germany and the new Bolshevik government of Russia. It awarded Germany with large areas of land in Poland, Ukraine, and Russia. This was in accordance with the Lebensraum concept supported by Hindenburg, which was advocated in parts of the German society and proposed large-scale annexations, ethnic cleansing, and Germanization in conquered territories. The concept was enhanced after the war by the Nazis and finally put into effect during World War II.[106][107] Hindenburg was also an advocate of the so-called Polish Border Strip plan, which postulated mass expulsion of Poles and Jews from territories that would be annexed by the German Empire, a foreshadow of the ethnic cleansing carried out decades later.[108][109][110] Even more extreme than the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk was the Treaty of Bucharest signed with Romania on 7 May 1918 whose terms included an indefinite German occupation of Romania, control of the Romanian oil industry for 99 years by a German state corporation and German control of the navigation on the Danube.[111] Under the terms the Treaty of Bucharest, German civil servants with the power of veto over the decisions by Romanian cabinet ministers and to fire Romanian civil servants were appointed to oversee every Romanian ministry, in effect stripping Romania of its independence.[112] Despite this, Ludendorff and Hindenburg felt that Kühlmann had been too "soft" on the Romanians, and reacted by having their spies (Kühlmann's chauffeur was a spy for the High Command) collect misinformation to be leaked to the German press; for instance, leaking a photo with Kühlmann posting with a young woman who was his secretary who was described as a "notorious Bucharest whore".[113]

Hindenburg and Ludendorff had little understanding of strategy or grand strategy, instead focusing on war in operational and tactical terms.[114] Operation Michael called for inflicting a series of annihilating defeats on the British and the French with the aim of winning the war in the spring of 1918.[115] Reflecting his obsession with the will to win as the key factor in war, Hindenburg said before Operation Michael: "I am convinced that we will win. Where the will is, the way is also found. So forward with God!".[116] On 21 March 1918, Operation Michael or the Kaiserschlacht (Emperor's Battle) was launched with 63 German divisions attacking the British 5th Army in the Arras-St. Quentin sector.[116] The new tactics for Operation Michael involved sudden, sharp bombardments of shrapnel, high explosives and numerous varieties of poison gas coordinated with specially trained elite troops wearing gas masks known as the stormtroopers advancing at the same time.[114] In face of these attacks, the 5th Army collapsed with 20, 000 dead and another 30, 000 surrendering.[94] The Kaiser personally disliked Hindenburg, but he hated the British even more, and following this victory he awarded the field marshal the Iron Cross with Golden Rays, a decoration only awarded once before to Field Marshal Blucher for the Battle of Waterloo in 1815.[94]

To take advantage of the huge, gaping hole he just created in the Allied lines, Ludendorff started an offensive in Amines sector with the aim of severing the British from the French and then racing to the English Channel in order to "annihilate" the entire British Expeditionary Force (BEF).[117] At the Doullens conference on 26 March 1918, the Allies created a Supreme Commander for the Western Front with Marshal Ferdinand Foch of France being appointed generalissimo with operational control over all British, French, American and other Allied forces on the Western Front .[118] The appointment of Foch as Allied generalissimo undercut one of the crucial assumptions behind Operation Michael, namely that the Allies would never coordinate their efforts.[118] Foch stopped the German drive upon Amiens with his Anglo-French forces.[118] Astore and Showalter noted that "Hindenburg especially praised the French for their timely counterattacks and skillful use of artillery that combined to weaken Germany's offensive strength".[118]

Despite the failure of Operation Michael, which had cost Germany about 60, 000 dead, Ludendorff and Hindenburg followed it with four more "victory offensives" between April–July 1918, all of which resulted in local gains with huge losses and all of which failed in strategic terms.[119] German soldiers started to complain that under the leadership of Hindenburg and Ludendorff were German Army was wir siegen uns zu Tode (we are conquering ourselves to death).[119] In desperation, an increasingly deranged Ludendorff immersed himself in details and continued to insist upon manically launching one offensive after another, believing that if he just kept on hitting the Allies something would have to give, leading Foch to comment: "Je me demande si Ludendroff connaît son métier?" ("I wonder if Ludendorff knows his job?").[119] Hindenburg did nothing to rein in Ludendorff.[119] Hindenburg and Ludendorff had developed the stormtroopers as a way of smashing through the Allied lines, but they lacked the logistical infrastructure to follow up their victories.[119] The German Army had only 36, 000 trucks, one-third of what the Allies possessed with the rest of their supplies being brought up by horse and wagon.[119] Germany had only ten tanks compared to the 800 tanks possessed by Britain and France.[120] Hindenburg had dismissed tanks as a weapon, saying: "It is always bad when an army tries, through technical innovation, to find a substitute for the spirit. That is irreplaceable".[121] To exploit the gaps in the Allied lines, the Germans used their infantry, which could always be slowed down for hours by one well-placed machine gun post.[120]

On 9 April 1918, Ludendorff launched Operation Georgette or the Lys Offensive, which targeted the British lines at Ypres.[122] Once again, the Germans made tactical gains without achieving a strategic success.[120] Concerned at the direction of the war, one officer Colonel Albrecht von Thaer travelled to the HQ at Avesnes to tell Hindenburg that Ludendorff's offensives were bleeding the Army to death.[123] Hindenburg assured Thaer that the problems he described were only "local" with situation elsewhere "very good" and "splendid" and Ludendorff dismissing Thear's reports as "prattle".[124] On 27 May 1918, Ludendorff launched Operation Blucher or the Aisne Offensive with began well when the Germans smashed the French 6th Army at Chemin des Dames.[125] With the French retreating in disorder, German troops raced across the Marne river.[126] The purpose of the offensive was to divert French troops from northern part of the line to allow the Germans to begin yet another offensive in Flanders to drive the BEF into the sea, but the temptation to try to take Paris proved too much for Ludendorff.[124] In its first major battle, the American Expeditionary Force stopped the German offensive towards Paris at the Battle of Chateau-Thierry and Belleau Wood.[127] On 9 June 1918, Ludendorff started the Noyon Offensive against the French, which gained only six miles before the French halted the Germans.[128] Following this defeat, the foreign state secretary Richard von Kühlmann suggested that since Hindenburg and Ludendorff had proved themselves incapable of winning the war, that now was the time to open peace talks.[129] Hindenburg and Ludendorff had Kühlmann dismissed for "defeatism" and replaced with the staunch annexationist, Admiral Paul von Hintze.[129] On 15 July 1918, Ludendorff launched his final "victory offensive" with again the aim of taking Paris, the Champagne Offensive which was stopped by the French 4th Army.[130]

Between March–July 1918, Germany had suffered over a million casualties on the Western Front while gaining three salients that vulnerable to pinching attacks while stretching out their supply lines.[129] Despite admitting that the ground gained by the five offensives was going to be difficult to defend, neither Ludendorff or Hindenburg would contemplate withdrawal which they viewed as an admission of defeat.[131] Foch saw an opening, recognising that by launching a series of attacks on the extended salients, he could force Ludendorff and Hindenburg to commit whatever reserves they had left while at same time the superior firepower of the Allies could inflict crushingly heavy casualties as the Germans brought up their reserves.[132] On 18 July 1918, Foch began the first of his counteroffensives on the Marne salient, which cost the Germans ten divisions.[132] From 18 July to 11 November 1918, Germany was to lose 425, 000 men killed and 340, 000 wounded.[133] Foch's offensive marked the beginning of the end of the "marriage" between Ludendorff and Hindenburg.[132] As Ludendorff was pacing back and forth, wondering what he should do, Hindenburg mentioned that he would like to start a counteroffensive against Foch's left-wing, an idea that Ludendorff dismissed as "utterly unfeasible" and "nonsense" as the reserves were lacking.[133] Hindenburg said "I should like a word with you" and took Ludendorff off to a private meeting, giving him a severe dressing-down for questioning his authority in public.[133] Afterwards, the friendly bonhomie between Hindenburg and Ludendorff was no more with the two men becoming increasingly cold and distant to each other.[133]

At the French ports, one American division was landed once every two days, making certain the Allies could replace all of their losses while Germany had no way of replacing its losses.[134] Despite the fact that war was going badly for Germany, Hindenburg continued to insist that the war could be won if only German soldiers would just fight harder with the Field Marshal ruling out any possibility of making peace with the Allies.[135] With defeat staring him in the face, Ludendorff become obsessed with details as by losing himself in minutia he avoided dealing with the larger picture while Hindenburg at his HQ in Spa told his staff to only tell him good news.[134] On 8 August 1918, there occurred the Battle of Amiens or the "Black Day of the German Army" as Ludendorff called it with the Canadian Corps of the BEF under General Sir Arthur Currie smashing a twenty mile long hole in the German line, through which raced Allied troops and tanks, pushing the Germans back 8 miles while inflicting 30,000 casualties and capturing 400 guns.[136] After Amiens, Ludendorff called for an armistice-not to make peace, but rather to give Germany a breathing space so that the war could be resumed in six months’ time.[137] At a meeting of the Crown Council at Spa on 14 August 1914, Hindenburg remained his calm self, insisting there was nothing to worry about despite the disaster at Amiens, arguing that the Allied offensive would be stopped and the war could be still be won if only everybody just stayed calm and kept their faith in the Fatherland as he was doing.[137] It was largely because of Hindenburg's insistence that the war could still be won that Germany did not sign an armistice in August 1918.[137] Hindenburg rarely visited the front, preferring the company of his HQ at Spa and by this point had no real understanding of what was happening at the front.[137]

By September 1918, all of the gains made since March had been lost and the Allies were attacking the Hindenburg Line.[137] On 29 September 1918, the French 1st Army supported by the British 3rd and 4th Armies broke through the Hindenburg Line.[138] Ludendorff had a nervous breakdown at the news, screaming hysterically that he been betrayed by Social Democrats and the Jews and none of the defeats suffered by the Germans were his fault.[138] Hindenburg stayed resolute, saying that perhaps the war could not be won after all, but he was certain he would stop the Allies and ensure at the peace talks, Germany would be able to annex the French iron-fields at Briey and Longwy, a suggestion that Ludendorff dimissed as fantasy.[138]

In September 1918, Ludendorff advised seeking an armistice with the Allies but, in October, he changed his mind and resigned in protest. Ludendorff had expected Hindenburg to follow him by also resigning, but Hindenburg refused on the grounds that, in this hour of crisis, he could not desert the men under his command. Ludendorff never forgave Hindenburg for this. Ludendorff was succeeded by Wilhelm Groener. On 1 October 1918, the German Crown Council issued a note calling "for the immediate offer of peace to spare useless sacrifices for the German people and their allies".[138] Hindenburg told the Crown Council on 2 October 1918 "there appears to be no possibility...of winning peace from our enemies by force of arms".[138] At this point, Hindenburg who had completely excluded the politicians from decision-making ever since August 1916 when he was appointed Chief of the General Staff, saying that only the military knew how to win the war, now insisted with the war lost that the Army would take no responsibility for the defeat and it was up to the politicians to negotiate an armistice.[139] On 3 October 1918, Hindenburg had Hertling who had been too closely associated with the annexationist peace treaties of Brest-Litovsk and Bucharest sacked as Chancellor and replaced with Prince Max of Baden, who as a liberal and a democrat was believed to be a man capable of getting lenient peace terms from President Wilson.[140] Having installed Prince Max as Chancellor and allowed the beginning of peace talks, on 17 October 1918 Hindenburg and Ludendorff now told the Crown Council of their opposition to an armistice and their wish for continuing the war, come what may, with Ludendorff calling for an Endkampf (final struggle), an apocalyptic last stand in every adult German would be given a gun and thrown into battle.[141] Ludendorff and Hindenburg did not expect their advice to be accepted.[141] Rather, they were engaging in a cynical ploy to ensure that the responsibility for the armistice did not rest with the Army, or perhaps more to the point, themselves.[141]

On 24 October 1918, Ludendorff and Hindenburg announced in an Order of the Day that the armistice terms proposed by President Wilson were "unacceptable to us soldiers at the front" and vowed to fight on to the bitter end.[142] The Order of the Day threatened to undermine the peace talks and Prince Max submitted his resignation to Wilhelm in protest, saying it was impossible as Chancellor to govern when the Army was outside of his control.[142] The Kaiser, finally seeing a chance to reassert his control over the Army summoned Hindenburg and Ludendorff for a meeting.[142] On 26 October 1916 at the meeting with Wilhelm, Ludendorff submitted his resignation as First Quartermaster-General, which Wilhelm all too willingly accepted while Hindenburg in a half-hearted way almost attempted to resign before deciding to stay on.[142] Ludendorff was furious with Hindenburg when he learned that he had not resigned with him, accusing him of being a shabby friend and chose not to ride in the same car with Hindenburg back to the Army HQ.[142] Prince Max was heard to shout "Thank God!" when he heard that Ludendorff had resigned, but was glad that Hindenburg, who was perceived as the more reasonable and sane of the two was staying on.[143] Hindenburg made a point of ensuring that the Army had little as possible to do with the armistice negotiations with a mere captain representing the Army at the talks, thus leaving the odium of signing the armistice to the politicians.[143] Hindenburg had expected Wilhelm to remain on the throne, but the mutiny of the High Seas Fleet on 4 November 1918 made the retention of the monarchy impossible.[143] On 9 November Hindenburg and Groener told Wilhelm II that the Army no longer obeyed the emperor and he would have to abdicate.[143] In November 1918, Hindenburg and Groener played a decisive role in persuading Emperor Wilhelm II to abdicate for the greater good of Germany. Hindenburg's first loyalty to the Army meant he wanted to extricate nation from a losing war and a revolution to preserve the basis of German power so to launch another world war to achieve the goals he failed to achieve in the First World War.[144] As such, Wilhelm's determination to retain his throne made him a liability to Hindenburg as the Allies would not sign an armistice with Wilhelm, which is why Hindenburg applied such strong pressure on him to abdicate.[145] Hindenburg had no sympathy with those conservatives for whom the November Revolution was the end of the world such as his son-in-law Count Joachim von Brockhusen, telling the latter that his main concern was to preserve the army to fight another world war some day and his first loyalty was to the Reich regardless if were was a monarchy or a republic.[146] The Kaiser was most unwilling to abdicate, instead advocating bizarre plans of making an alliance with Britain against the United States in a desperate bid to keep his throne, and had to be told repeatedly by Groener to abdicate with Hindenburg silently nodding his head in support.[147]

Hindenburg was a firm monarchist throughout his life and always regarded this episode with considerable embarrassment. Almost from the moment that the emperor abdicated, Hindenburg insisted that he had played no role in it. Instead, he assigned all of the blame to Groener. Groener, for his part, went along in order to protect Hindenburg's reputation.[148] Shortly afterwards, the President of the new republic, Frederich Elbert made a silent pact with Groner known as the Groner-Elbert pact under the Army would crush the growing Communist movement in Germany in exchange for which it would maintain its unofficial "state within the state" status.[149]

Aftermath of the war

In June 1919, when the Allies submitted the Treaty of Versailles for the Reichstag to ratify, the President Friedrich Ebert was in favor of rejecting the treaty and resuming the war.[150] As such, Ebert asked the military what were the possibilities of the Reich winning if the war resumed in June 1919.[150] Groner advised acceptance of the treaty under the grounds that Allies would win the war if it resumed and that the terms of Versailles treaty left the Reich intact and allowed for the possibility of Germany regaining great power status one day, observing the treaty did not destroy the basis of German power.[151] Hindenburg felt the same way, but argued at a meeting with Ebert and Groner that: "Should we not appeal to the Corps of Officers and demand from a minority of the people a gesture of sacrifice in defence of our national honor?".[152] Groner replied: "The significance of such a gesture would escape the German people. There would be a general outcry against counter-revolution and militarism. The result would be the downfall of the Reich. The Allies, baulked of their hopes of peace, would show themselves pitiless. The Officer Corps would be destroyed and the name of Germany would disappear from the map".[152] Hindenburg could not rebut Groner's argument, but still offered only half-hearted support, writing to Ebert on 17 June 1919: "In the event of a resumption of hostilities, we can reconquer the province of Posen and defend our frontiers in the East. In the West, however we can scarcely count upon being able to withstand a serious offensive on the part of the enemy in view of the numerical superiority of the Entente and their ability to outflank us on both wings. The success of the operation as a whole is therefore very doubtful, but as a soldier I cannot help feeling it were better to perish honourably than accept a disgraceful peace".[152] The Allies submitted an ultimatum saying that Germany had 72 hours to sign the Treaty of Versailles before the war resumed. On 23 June 1919 with only 7 hours left before the ultimatum expired, Ebert contacted Groner and Hindenburg to ask for their advice as professional military men about what he should do.[153] Hindenburg refused to speak, and let Groner do all the talking as Groner advised acceptance.[154] After hearing Groner's advice, with just 19 minutes to go, Ebert sent a message to the French Premier Georgres Clemenceau saying Germany would ratify the Treaty of Versailles, which was signed on 28 June 1919.[155] The British historian Sir John Wheeler-Bennett wrote that Hindenburg's behavior in June 1919 closely resembled his actions in November 1918 where Groner had to pressure Wilhelm II to abdicate while he remained silent.[155] Wheeler-Bennett further charged that in June 1919, the real Hindenburg revealed himself; not the titanic, larger-than-life figure beloved by the German people, the "rock" upon which the Reich rested, but rather "a poor thing, a thing of plaster and of papier mâché."[155] Wheeler-Bennett wrote Hindenburg knew the truth, but chose to do the easy thing by having his faithful aide Groner say all the things that he knew to be true while maintaining the pretense that he had been opposed to accepting Versailles, a sign of both Hindenburg's deeply dishonest nature and his tendency to evade responsibility whenever responsibility became difficult.[150]

In the summer of 1919, Hindenburg retired a second time and announced his intention to leave public life. By 1919, Hindenburg's ego had reached such a point that equated criticism of himself as practically treason, writing: "The only existing idol of the nation, undeservedly my humble self, runs the risk of being torn from its pedestal once it becomes the target of criticism.".[156] In 1919, he was called before a parliamentary commission that was investigating the responsibility for both the outbreak of war in 1914 and for the defeat in 1918.[157] Hindenburg had not wanted to appear before the commission but he had been subpoenaed. His appearance became an eagerly awaited public event. Ludendorff had fallen out with Hindenburg over the decision to continue seeking the armistice in October 1918, and he was concerned that Hindenburg might reveal that it was he who had advised seeking an armistice the previous month, and had insisted that he would not testify unless Hindenburg was also subpoenaed.[158] Ludendorff wrote a letter to Hindenburg to inform him that he was writing his memoirs and was prepared to expose the fact that Hindenburg did not deserve the credit that he had received for his victories. Ludendorff's letter went on to suggest that Hindenburg's testimony would determine how favorably Ludendorff would present him in his memoirs.

When Hindenburg did appear before the commission on 18 November 1919, he refused to answer any questions about the responsibility for the German defeat and instead read out a prepared statement that had been reviewed in advance by Ludendorff's lawyer.[159] Hindenburg testified that the German Army had been on the verge of winning the war in the autumn of 1918 and that the defeat had been precipitated by a Dolchstoß ("stab in the back") by disloyal elements on the home front and unpatriotic politicians, saying that an unnamed British general had said "The German Army was stabbed in the back."[160] Hindenburg's statement had nothing to with the question he asked about what was his responsibility for the decision for launch unrestricted submarine warfare despite the risk it would bring America into the war.[161] Hindenburg simply walked out of the hearings after reading his statement, despite being threatened with a contempt citation for refusing to respond to questions.[160] Hindenburg's status as a war hero provided him with a political shield; he was never prosecuted. Hindenburg's testimony constituted the first use of the Dolchstoßlegende, and the term was adopted by nationalist and conservative politicians who sought to blame the socialist founders of the Weimar Republic for the loss of the war. The reviews in the German press that had grossly misrepresented general Frederick Barton Maurice's book The Last Four Months contributed to the creation of this myth. Ludendorff made use of the reviews to convince Hindenburg.[162]

In a hearing before the Committee on Inquiry of the National Assembly on 18 November 1919, a year after the war's end, Hindenburg declared, "As an English general has very truly said, the German Army was 'stabbed in the back'."[162]

Afterwards, Hindenburg had his memoirs ghost-written in 1919–20.[163] The resulting book Mein Leben (My Life) was a huge bestseller in Germany, but it was dismissed by most military historians and critics as a boring apologia that skipped over the most controversial issues in Hindenburg's life.[164] The major themes of the book was the need to Germany to maintain a strong military as the military was "the school of the nation" that taught young German men the proper moral values and the need to restore the monarchy as Hindenburg insisted that only under the leadership of the House of Hohenzollern could Germany become great again.[165] Partly reflecting guilt over pressuring Wilhelm to abdicate and partly because the book was written to serve as manifesto to appeal to conservative voters for the presidential run Hindenburg was contemplating, Mein Leben went out of its way to praise Wilhelm II who was always "my Emperor" and "my Supreme Warlord", and Hindenburg even made the ludicrous claim that it was Wilhelm I who had unified Germany with only very limited assistance from Bismarck.[166] In 1919–20, Hindenburg considered running for president and wrote to Wilhelm II in exile in the Netherlands for permission to run.[167] Wilhelm gave his approval, believing that if Hindenburg was elected president he would restore the monarchy, and 8 March 1920 Hindenburg announced his intention to seek the presidency.[168] As it was the planned presidential election of 1920 was cancelled and in the backlash against the right caused by the Kapp Putsch, Hindenburg had already withdrawn his candidacy.[169] Afterwards, Hindenburg retired from most public appearances and spent most of his time with his family. Hindenburg was a widower and was very close to his only son Major Oskar von Hindenburg and his granddaughters.

Presidency

1925 election

In 1925, Hindenburg was urged to run for the office of President of Germany. In spite of his lack of interest in holding public office, he decided to stand for the post anyway. No candidate had emerged with a majority in the first round of the presidential election held on 29 March 1925, and a run-off election had been called. Social Democratic candidate Otto Braun, the Prime Minister of Prussia, had agreed to drop out of the race and had endorsed the Catholic Centre Party's candidate Wilhelm Marx. Karl Jarres was the joint candidate of the two conservative parties: the German People's Party (DVP) and the German National People's Party (DNVP). He was regarded as too dull, and it seemed likely that Marx would win. Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz, one of the leaders of the DNVP, visited Hindenburg and urged him to run.