Pendred syndrome

| Pendred syndrome | |

|---|---|

| |

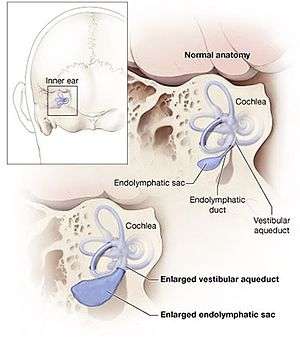

| The cochlea normally has 2 & a half turns, but, in pendred syndrome, there can be 1 & a half turn only because of abnormal dilatation of an endolymphatic sack. | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | endocrinology |

| ICD-10 | E07.1 |

| OMIM | 274600 |

| DiseasesDB | 9771 |

| GeneReviews | |

Pendred syndrome or Pendred disease is a genetic disorder leading to congenital bilateral (both sides) sensorineural hearing loss and goitre with euthyroid or mild hypothyroidism (decreased thyroid gland function). There is no specific treatment, other than supportive measures for the hearing loss and thyroid hormone supplementation in case of hypothyroidism. It is named after Dr Vaughan Pendred (1869–1946), the English doctor who first described the condition in an Irish family living in Durham in 1896.[1][2] It accounts for 7.5% of all cases of congenital deafness.[3]

Signs and symptoms

The hearing loss of Pendred's syndrome is often, although not always, present from birth, and language acquisition may be a significant problem if deafness is severe in childhood. The hearing loss typically worsens over the years, and progression can be step-wise and related to minor head trauma. In some cases, language development worsens after head injury, demonstrating that the inner ear is sensitive to trauma in Pendred syndrome; this is as a consequence of the widened vestibular aqueducts usual in this syndrome.[3] Vestibular function varies in Pendred syndrome and vertigo can be a feature of minor head trauma. A goitre is present in 75% of all cases.[3]

Genetics

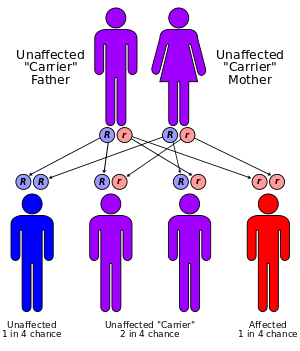

Pendred syndrome inherits in an autosomal recessive manner, meaning that one would need to inherit an abnormal gene from each parent to develop the condition. This also means that a sibling of a patient with Pendred's syndrome has a 25% chance of also having the condition if the parents are unaffected carriers.

It has been linked to mutations in the PDS gene, which codes for the pendrin protein (solute carrier family 26, member 4, SLC26A4). The gene is located on the long arm of chromosome 7 (7q31).[4][5] Mutations in the same gene also cause enlarged vestibular aqueduct syndrome (EVA or EVAS), another congenital cause of deafness; specific mutations are more likely to cause EVAS, while others are more linked with Pendred syndrome.[6]

Pathophysiology

SLC26A4 can be found in the cochlea (part of the inner ear), thyroid and the kidney. In the kidney, it participates in the secretion of bicarbonate. However, Pendred's syndrome is not known to lead to kidney problems.[7] It functions as an iodide/chloride transporter. In the thyroid, this leads to reduced organification of iodine (i.e. its incorporation into thyroid hormone).[4]

Diagnosis

Audiometry (measuring ability to hear sounds of a particular pitch) is usually abnormal, but the findings are not particularly specific and an audiogram is not sufficient to diagnose Pendred's syndrome. A thyroid goitre may be present in the first decade and is usual towards the end of the second decade. MRI scanning of the inner ear usually shows widened or large vestibular aqueducts with enlarged endolymphatic sacs and may show abnormalities of the cochleae that is known as Mondini dysplasia.[3] Genetic testing to identify the pendrin gene usually establishes the diagnosis. If the condition is suspected, a "perchlorate discharge test" is sometimes performed. This test is highly sensitive, but may also be abnormal in other thyroid conditions.[3] If a goitre is present, thyroid function tests are performed to identify mild cases of thyroid dysfunction even if they are not yet causing symptoms.[8]

Treatment

No specific treatment exists for Pendred syndrome. Speech and language support and cochlear implants may improve language skills.[8] If thyroid hormone levels are decreased, thyroid hormone supplements may be required. Patients are advised to take precautions against head injury.[8]

References

- ↑ Pendred V (1896). "Deaf-mutism and goitre". Lancet. 2 (3808): 532. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(01)74403-0.

- ↑ Pearce JM (2007). "Pendred's syndrome". Eur. Neurol. 58 (3): 189–90. doi:10.1159/000104724. PMID 17622729.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Reardon W, Coffey R, Phelps PD, et al. (July 1997). "Pendred syndrome--100 years of underascertainment?" (PDF). QJM. 90 (7): 443–7. doi:10.1093/qjmed/90.7.443. PMID 9302427.

- 1 2 Sheffield VC, Kraiem Z, Beck JC, et al. (April 1996). "Pendred syndrome maps to chromosome 7q21-34 and is caused by an intrinsic defect in thyroid iodine organification". Nat. Genet. 12 (4): 424–6. doi:10.1038/ng0496-424. PMID 8630498.

- ↑ Coyle B, Coffey R, Armour JA, et al. (April 1996). "Pendred syndrome (goitre and sensorineural hearing loss) maps to chromosome 7 in the region containing the nonsyndromic deafness gene DFNB4". Nat. Genet. 12 (4): 421–3. doi:10.1038/ng0496-421. PMID 8630497.

- ↑ Azaiez H, Yang T, Prasad S, et al. (December 2007). "Genotype-phenotype correlations for SLC26A4-related deafness". Hum. Genet. 122 (5): 451–7. doi:10.1007/s00439-007-0415-2. PMID 17690912.

- ↑ Royaux IE, Wall SM, Karniski LP, et al. (March 2001). "Pendrin, encoded by the Pendred syndrome gene, resides in the apical region of renal intercalated cells and mediates bicarbonate secretion". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98 (7): 4221–6. doi:10.1073/pnas.071516798. PMC 31206

. PMID 11274445.

. PMID 11274445. - 1 2 3 National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (October 2006). "Pendred Syndrome". Retrieved 2008-05-05.