Phil Lynott

| Phil Lynott | |

|---|---|

|

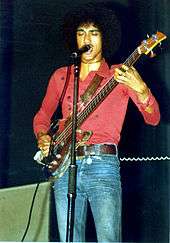

Lynott performing in Oslo, Norway on 22 April 1980. | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Philip Parris Lynott |

| Born |

20 August 1949 West Bromwich, Staffordshire, England |

| Origin | Dublin, Ireland |

| Died |

4 January 1986 (aged 36) Salisbury, Wiltshire, England |

| Genres | Rock, pop, folk, blues rock, blues |

| Occupation(s) | Musician, songwriter, producer, poet |

| Instruments | Vocals, bass guitar, guitar |

| Years active | 1965–85 |

| Labels | Vertigo, Mercury, Warner Bros. |

| Associated acts | Thin Lizzy, Gary Moore, Wild Horses, The Greedies, Skid Row, Grand Slam, John Sykes, Midge Ure |

| Notable instruments | |

|

Early Dan Armstrong Lucite Bass Rickenbacker 4001 bass Mid Fender Precision Bass Late Ibanez Roadstar Bass | |

Philip Parris "Phil" Lynott (/ˈlaɪnət/; 20 August 1949 – 4 January 1986) was an Irish musician, singer and songwriter. His most commercially successful group was Thin Lizzy, of which he was a founding member, the principal songwriter, lead vocalist and bassist. He later also found success as a solo artist.

Growing up in Dublin in the 1960s, Lynott fronted several bands as a lead vocalist, most notably Skid Row alongside Gary Moore, before learning the bass guitar and forming Thin Lizzy in 1969. After initial success with "Whiskey in the Jar", the band found strong commercial success in the mid-1970s with hits such as "The Boys Are Back in Town", "Jailbreak" and "Waiting for an Alibi", and became a popular live attraction due to the combination of Lynott's vocal and songwriting skills and the use of dual lead guitars. Towards the end of the 1970s, Lynott also embarked upon a solo career, published two books of poetry,[1] and after Thin Lizzy disbanded, he assembled and fronted the band Grand Slam, of which he was the leader until it folded in 1985.

He subsequently had major UK success with Moore with the song "Out in the Fields", followed by the minor hit "Nineteen", before his death on 4 January 1986. He remains a popular figure in the rock world, and in 2005, a statue to his memory was erected in Dublin.

Early life

Lynott was born in Hallam Hospital (now Sandwell General Hospital) in West Bromwich (then in Staffordshire), England, and christened at St. Edwards Church in Selly Park, Birmingham. His mother, Philomena Lynott was born in Dublin on 22 October 1930, [2][3] and his father, Cecil Parris, was from Georgetown, British Guiana.[4][5] Philomena met Parris in Birmingham in 1948, having moved to England to seek work and they were in a relationship for a few months, until Parris was transferred to London.[2] Shortly afterwards, Philomena found she was pregnant and, after Philip was born, she moved with her baby to a home for unmarried mothers in Selly Oak, Birmingham. When Parris learned of Philip's birth, he returned to Birmingham and arranged accommodation for Philomena and Philip in nearby Blackheath. Her relationship with Parris lasted two more years although he was still working in London and they did not live together. Philomena subsequently moved to Manchester but stayed in touch with Parris and, although she turned down a marriage proposal from him, he agreed to pay towards his son's support.[6]

When he was four years old, Philip went to live with his grandmother, Sarah Lynott, in Crumlin, Dublin.[7] His mother stayed in Manchester, and later took over the management of the Clifton Grange Hotel in Whalley Range with her partner, Dennis Keeley.[8] The hotel, nicknamed "The Biz", became popular with showbusiness entertainers, and was later referred to in a song on Thin Lizzy's debut album.[9] Lynott had a happy childhood growing up in Dublin, and was a popular character at school.[10]

Music career

Early years

Lynott was introduced to music through his uncle Timothy's record collection, and became influenced by Tamla Motown and The Mamas & the Papas. He joined his first band, the Black Eagles in 1965 as a lead singer, playing popular covers in local clubs around Dublin.[11][3] He attended the Christian Brothers School in Crumlin, where he became friends with Brian Downey, who was later persuaded to join the band from the Liffey Beats.[12] The group fell apart due to the lack of interest of manager Joe Smith, particularly after the departure of his two sons, guitarists Danny and Frankie.[13]

Lynott then left the family home and moved into a flat in Clontarf, where he briefly joined 'Kama Sutra'. It was in this band that he learned his frontman skills, and worked out how to interact with an audience.[14] In early 1968, he teamed up with bassist Brendan 'Brush' Shiels to form Skid Row. Shiels also wanted Downey to play drums in the band, but Downey wasn't interested in the band's style, so the job went to Noel Bridgeman instead.[15] The band signed a deal with Ted Carroll, who would later go on to manage Thin Lizzy, and played a variety of covers including "Eight Miles High", "Hey Jude" and several numbers by Jimi Hendrix.[16] Because Lynott did not play an instrument at this point in his career, he instead manipulated his voice through an echo box during instrumental sections. He also took to smearing boot polish under his eyes on stage, which he would continue to do throughout Lizzy's career later on, and regularly performed a mock fight with Shiels onstage to attract the crowd.[17] In mid 1968, guitarist Bernard Cheevers quit to work full-time at the Guinness factory in Dublin, and was replaced by Belfast-born guitarist Gary Moore.[18]

Despite increased success, and the release of a single, New Faces, Old Places, Shiels became concerned about Lynott's tendency to sing off-key. He then discovered that the problem was with Lynott's tonsils; he subsequently took a leave of absence from the band. By the time he had recovered, Shiels had decided to take over singing lead and reduce the band to a three piece. Feeling guility of having effectively sacked one of his best friends, he taught Lynott how to play bass, figuring it would be easier to learn than a six string guitar, and sold him a Fender Jazz Bass he had bought from Robert Ballagh for £36, and started giving him lessons.[19]

Lynott and Downey quickly put together a new band called 'Orphanage', with guitarist Joe Staunton and bassist Pat Quigley, playing a mixture of original material alongside covers of Bob Dylan, Free and Jeff Beck.[20] Still learning the bass, Lynott restricted himself to occasional rhythm guitar alongside singing lead.[21]

At the end of 2006 a number of Skid Row and Orphanage demo tapes featuring Phil Lynott were discovered. These were his earliest recordings and had been presumed lost for decades.[22]

Thin Lizzy

Towards the end of 1969, Lynott and Downey were introduced to guitarist Eric Bell via founding member of Them, keyboardist Eric Wrixon. (Bell had also played in a later line-up of Them). Deciding that Bell was a better guitarist, and with Lynott now confident enough to play bass himself in a band, the four of them formed Thin Lizzy[23] The name came from the character "Tin Lizzie" in the comic The Dandy.[24][25] The "h" was deliberately added to mimic the way the word "thin" is pronounced in a Dublin accent.[26] Lynott later discovered Henry Ford's slogan for the Model T, "Any colour you like as long as it's black", which he felt was appropriate for him.[26] Wrixon was felt by the others to be superfluous to requirements and left after the release of the band's first single, The Farmer in July 1970.[23]

During the band's early years, despite being the singer, bassist and chief songwriter, Lynott was still fairly reserved and introverted on stage, and would stand to one side while the spotlight concentrated on Bell, who was initially regarded as the group's leader.[27] During the recording of the band's second album, Shades of a Blue Orphanage, Lynott very nearly left Thin Lizzy to form a new band with Deep Purple's Ritchie Blackmore and Ian Paice. He decided he would rather build up Lizzy's career from the ground up than jump into another band that had big-name musicians in it. Due to being in dire financial straits, Lizzy did, however, soon afterwards record an album of Deep Purple covers anonymously under the name Funky Junction. Lynott did not sing on the album as he felt his voice was not in the same style as Ian Gillan.[28]

Towards the end of 1972, Thin Lizzy got their first major break in the UK by supporting Slade, then nearing the height of their commercial success. Inspired by Noddy Holder's top hat with mirrors, Lynott decided to attach a mirror to his bass, which he carried over to subsequent tours. On the opening night of the tour, an altercation broke out between Lynott and Slade's manager Chas Chandler, who chastised his lack of stage presence and interaction with the audience, and threatened to throw Lizzy off the tour unless things improved immediately. Lynott subsequently developed his onstage rapport and stage presence that would become familiar over the remainder of the decade.[29]

Thin Lizzy's first top ten hit was in 1973, with a rock version of the traditional Irish song "Whiskey in the Jar",[3] featuring a cover by Irish artist and friend, Jim Fitzpatrick.[30] However, follow up singles failed to chart, and after the departure of Bell, quickly followed by replacement Moore, and Downey, led Thin Lizzy to near collapse in mid 1974.[31] It was not until the recruitment of guitarists Scott Gorham and Brian Robertson, and the release of Jailbreak in 1976, that Thin Lizzy became international superstars on the strength of the album's biggest hit, "The Boys Are Back in Town". The song reached the top 10 in the UK, No. 1 in Ireland and was a hit in the US and Canada.[32] However, while touring with Rainbow, Lynott contracted hepatitis and the band had to cancel touring.[33]

"I used to note specifically these shady characters ... who used to turn up backstage. I knew they were drug-pushers and I made an effort to stop them getting passes. He [Lynott] said 'They're my mates!' But I said, 'No Phil, they're not your mates.'"

—Thin Lizzy tour manager Adrian Hopkins, on the band's latter touring days[34]

Lynott befriended Huey Lewis while his band, Clover, was supporting them on tour. Lewis was impressed with Lynott's frontman abilities, and was inspired to perform better, eventually achieving commercial success in the 1980s.[35] Lynott's writing was influenced by the band's US touring, including "Cowboy Song" and "Massacre", and he had a particular affinity for Los Angeles.[36]

Having finally achieved mainstream success, Thin Lizzy embarked on several consecutive world tours. The band continued on Jailbreak's success with the release of a string of hit albums, including Bad Reputation and Black Rose: A Rock Legend, and the live album Live and Dangerous, which features Lynott in the foreground on the cover.[37] However, the band was suffering from personnel changes, with Robertson being replaced temporarily by Moore in 1976,[38] and then permanently the following year, partly due to a personal clash with Lynott.[39]

By the early 1980s, Thin Lizzy were starting to struggle commercially, and Lynott started showing symptoms of drug abuse, including regular asthma attacks. After the resignation of longtime manager Chris O'Donnell, and Gorham wanting to quit, Lynott decided to disband Thin Lizzy in 1983.[40] He had started to use heroin by this stage in his career, and it affected the band's shows in Japan when he was unable to obtain any.[41] He managed to pick himself up for the band's show at the Reading Festival and their last ever gig (with Lynott as frontman) in Nuremberg on 4 September.[42]

Later years

In 1978, Lynott began to work on projects outside of Thin Lizzy. He was featured in Jeff Wayne's Musical Version of The War of the Worlds, singing and speaking the role of Parson Nathaniel on "The Spirit of Man". He performed sessions for a number of artists, including singing backing vocals with Bob Geldof on Blast Furnace and the Heatwaves' "Blue Wave" EP.[43] He was a judge at the 1978 Miss World contest.[44]

Lynott took a keen interest in the emergence of punk rock in the late 1970s, and subsequently became friends with various members of The Sex Pistols, The Damned and Geldof's band The Boomtown Rats. This led to him forming an ad-hoc band known as "The Greedies" (originally "The Greedy Bastards", but edited for public politeness). The band started playing shows in London during Lizzy's downtime in 1978, playing a mixture of popular Lizzy tracks and Pistols songs recorded after John Lydon's departure.[45] In 1979, The Greedies recorded a Christmas single, "A Merry Jingle", featuring other members of Thin Lizzy as well as the Pistols' Steve Jones and Paul Cook. The previous year he had performed alongside Jones and Cook on Johnny Thunders' debut solo album So Alone.[46] Lynott became friends with The Rich Kids' Midge Ure, who deputised for Thin Lizzy during 1979 shortly after joining Ultravox. Lynott persuaded Lizzy's management to sign Ultravox.[47]

In 1980, though Thin Lizzy were still enjoying considerable success, Phil Lynott launched a solo career with the album, Solo in Soho: this was a Top 30 UK album and yielded two hit singles that year, "Dear Miss Lonelyhearts" and "King's Call". The latter was a tribute to Elvis Presley, and featured Mark Knopfler on guitar.[48] His second solo venture, The Philip Lynott Album was a chart flop, despite the presence of the single "Old Town". The song "Yellow Pearl" (1982), was a No. 14 hit in the UK and became the theme tune to Top of the Pops.[49]

In 1983, following the disbanding of Thin Lizzy, Lynott recorded a rock'n'roll medley single, "We Are The Boys (Who Make All The Noise)" with Roy Wood, Chas Hodges and John Coghlan. Phil regularly collaborated with former bandmate Gary Moore on a number of tracks including the singles "Parisienne Walkways" (a No. 8 UK hit in 1979) and "Out in the Fields" (a No. 5 UK hit in 1985, his highest-charting single).[50] In 1984, he formed a new band, Grand Slam, with Doish Nagle, Laurence Archer, Robbie Brennan and Mark Stanway.[51] The band toured The Marquee and other clubs, but suffered from being labelled a poor version of Thin Lizzy due to the inclusion of two lead guitar players,[52] and split up at the end of the year due to a lack of money and Lynott's increasing addiction to heroin.[53]

During 1983–85, Lynott co-wrote a number of songs with British R&B artist Junior Giscombe, although nothing was ever officially released and most remain as demos. However, one of the songs, "The Lady Loves to Dance", was mastered with producer Tony Visconti and nearly released before being pulled by the record company, Phonogram.[54] Lynott was particularly upset about not being asked to participate in Live Aid, which had been organised by his two friends, Geldof and Ure, the latter of whom had briefly stood in as a guitarist for Thin Lizzy. Geldof later said this was because the Band Aid Trust could only accommodate time for extremely commercial successful artists selling millions of albums, which neither Lynott nor Thin Lizzy had done.[55]

His last single, "Nineteen", released a few weeks before his death, was produced by Paul Hardcastle. It bore no relation to the producer's chart-topping single of the same title some months earlier.[56] Throughout December 1985, Lynott had been promoting the track and this included performing live on various television shows. The same month, he gave his final interview in which he promulgated his possible plans for the near future; these included more work with Gary Moore and even the possibility of reforming Thin Lizzy, something which he had privately discussed with Scott Gorham previously. He also recorded some material with Archer, Huey Lewis, and members of Lewis's band the News in 1985, which was not released.[56]

Poetry books

Lynott's first book of poetry, "Songs for While I'm Away", was published in 1974. It contained 21 poems which were all lyrics from Thin Lizzy songs, except one titled "A Holy Encounter". Only 1000 copies of the book were printed.[1] In 1977, a second volume was released, titled "Philip".[57] In 1997, both books were brought together in a single volume, again titled "Songs for While I'm Away". This compendium edition also featured illustrations by Tim Booth and Thin Lizzy artist Jim Fitzpatrick, and the original introductions by Peter Fallon and John Peel.[1]

Personal life

On 14 February 1980,[58] Lynott married Caroline Crowther, the daughter of British comedian Leslie Crowther.[3] He met her when she was working for Tony Brainsby in the late 1970s. They had two children: Sarah (b. 19 December 1978[43]), for whom the eponymous 1979 song was written, and Cathleen (b. 29 July 1980[59]), for whom the eponymous 1982 Lynott solo song was written.[3] The marriage fell apart during 1984 after Lynott's drug use escalated.[60]

Lynott also had a son, born in 1968, who had been put up for adoption. In 2003, Macdaragh Lambe learned that Lynott was his biological father, and this was confirmed by Philomena Lynott in a newspaper interview in July 2010.[61]

Born in England and raised in Ireland, Lynott always considered himself to be Irish. His friend and Thin Lizzy bandmate Scott Gorham said in 2013: "Phil was so proud of being Irish. No matter where he went in the world, if we were talking to a journalist and they got something wrong about Ireland, he'd give the guy a history lesson. It meant a lot to him."[62] In the early 1980s, he purchased several properties in Howth, County Dublin, one of which, White Horses, was a 50th birthday present for his mother.[63]

Lynott was a passionate football fan, and a keen Manchester United supporter. He was good friends with United and Northern Ireland star George Best, and the pair regularly socialised at the Clifton Grange Hotel. Lynott later became a shareholder of the club.[64]

Lynott was also a team captain on the popular 1980s BBC quiz show Pop Quiz, hosted by Mike Read. He was captain against Alvin Stardust in 1984, on an infamous episode where Morrissey regretted ever taking part in the show.[65]

Death

Lynott's last years were dogged by drug and alcohol dependency leading to his collapse on 25 December 1985, at his home in Kew. He was discovered by his mother, who was not aware of his dependence on heroin. She contacted his wife Caroline, who knew about it and immediately identified the problem as serious.[66] After Caroline drove him to a drug clinic at Clouds House in East Knoyle, near Warminster, he was taken to Salisbury Infirmary where he was diagnosed as suffering from septicaemia.[3][56] Although he regained consciousness enough to speak to his mother, his condition worsened by the start of the new year and he was put on a respirator.[67] He died of pneumonia and heart failure due to septicaemia in the hospital's intensive care unit on 4 January 1986, at the age of 36.[3]

Lynott's funeral was held at St Elizabeth's Church, Richmond on 9 January 1986, with most of Thin Lizzy's ex-members in attendance, followed by a second service at Howth Parish Church on 11 January. He was buried in St Fintan's Cemetery, Sutton, Dublin.[68]

Legacy

"I still listen to his music every single day ... I go over and I pour water on to his gravestone. ... Then when I leave I give him a kick... for breaking my heart."

Thin Lizzy regrouped for a one-off performance in 1986, with Lynott's friend Bob Geldof taking lead vocals, and subsequently reformed as a touring act in 1996. In 2012, the members of Thin Lizzy decided to record new material, but chose to do so under the name of Black Star Riders as they and Lynott's widow felt uncomfortable about new Thin Lizzy recordings without Lynott.[70]

Each year since 1987 Lynott's friend Smiley Bolger hosts a festival for him on the anniversary of his death called the Vibe for Philo. A number of musicians perform at the festival annually including Thin Lizzy tribute bands and, occasionally, former Thin Lizzy members.[71][72] On 4 January 1994, a trust in Lynott's name was formed by his family and friends to provide scholarships for new musicians, and to make donations to charities and organisations in his memory.[73]

In 2005, a life-size bronze statue of Lynott was unveiled on Harry Street, off Grafton Street in Dublin. The ceremony was attended by Lynott's mother, and former band members Gary Moore, Eric Bell, Brian Robertson, Brian Downey, Scott Gorham and Darren Wharton, who performed live.[74] His grave in St Fintan's Cemetery in Sutton, northeast Dublin, is regularly visited by family, friends and fans.[75]

As well as reissues of Thin Lizzy material, Lynott's solo work has also seen retrospective releases. In April 2007, the 1996 film The Rocker: A Portrait of Phil Lynott, which consisted mainly of archive footage, was released on DVD in the UK.[76] In August 2010, Yellow Pearl was released. This is a collection of songs from Lynott's solo albums, B-sides and album tracks.[77]

In September 2012, both Lynott's mother and widow objected to Mitt Romney's use of "The Boys Are Back in Town" during his election campaign. In an interview with Irish rock magazine Hot Press, Philomena Lynott said, "As far as I am concerned, Mitt Romney's opposition to gay marriage and to civil unions for gays makes him anti-gay – which is not something that Philip would have supported."[78][79]

Philomena has struggled to come to terms with her son's death and visits his grave on a regular basis.[69]

Discography

- Solo in Soho (1980)

- The Philip Lynott Album (1982)

- Live in Sweden 1983 (2001)

- Yellow Pearl (2010)

With others

- Jeff Wayne: Jeff Wayne's Musical Version of The War of the Worlds (Columbia, 1978) as Parson Nathaniel

- Gary Moore: Back on the Streets (MCA, 1978), appears on "Back on the Streets", "Don't Believe a Word", "Fanatical Fascists", "Parisienne Walkways" and "Spanish Guitar"

- John Sykes: Please Don't Leave Me (MCA, 1982)

- Gary Moore: Run for Cover (Virgin, 1985), appears on "Military Man", "Out in the Fields" and "Still in Love with You"

See also

- Gary Moore and Friends: One Night in Dublin: A Tribute to Phil Lynott (Eagle Rock Entertainment, 2006)

Instruments and gear

- Rickenbacker 4001 bass (Early years)[80]

- Fender Precision bass with custom 'mirror' pickguard[81]

- Ibanez Roadstar RS900 (Late years)

- Danelectro Six String Bass

- Dan Armstrong Lucite Bass (Early years)

- Fender Stratocaster guitar

- Fender Telecaster guitar (Above two seen in promo videos for "Whiskey in the Jar")

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Phil Lynott. |

References

Footnotes

- 1 2 3 Lynott, Philip (1997). Songs for While I'm Away. Boxtree. ISBN 978-0-752-20389-8.

- 1 2 Byrne 2006, p. 12.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Thin Lizzy star dies". BBC News. 4 January 2006. Retrieved 24 June 2015.

- ↑ ""Phil Lynott's lost family", Daily Express, 23 August 2009". Daily Express. 23 August 2009. Retrieved 2011-07-17.

- ↑ Jason O'Toole (25 July 2010). "Now she tells of the second son and daughter she gave up for adoption". Daily Mail. Retrieved 25 July 2010.

- ↑ Lynott, Philomena; Hayden, Jacqueline (1995). My Boy: The Philip Lynott Story. Virgin Books. ISBN 978-0-753-50048-4.

- ↑ Byrne 2006, p. 14.

- ↑ Byrne 2006, pp. 16–17.

- ↑ Putterford 1994, pp. 16–17.

- ↑ Byrne 2006, p. 15.

- ↑ Putterford 1994, pp. 15–16.

- ↑ Putterford 1994, p. 23.

- ↑ Putterford 1994, p. 26.

- ↑ Putterford 1994, p. 28.

- ↑ Putterford 1994, p. 29.

- ↑ Putterford 1994, p. 30.

- ↑ Putterford 1994, p. 31.

- ↑ Putterford 1994, p. 33.

- ↑ Putterford 1994, pp. 33–35.

- ↑ Putterford 1994, p. 37.

- ↑ Byrne 2006, p. 25.

- ↑ "Fans' joy as Lynott demos unearthed". Rte.ie. 5 January 2007. Retrieved 9 October 2013.

- 1 2 Putterford 1994, p. 47.

- ↑ Alan Byrne (1 Feb 2006). Thin Lizzy. SAF Publishing Ltd. p. 30.

- ↑ Harry Doherty (20 Nov 2012). Thin Lizzy: The Boys Are Back in Town. Music Sales Group. p. 30.

- 1 2 Byrne 2006, p. 30.

- ↑ Putterford 1994, p. 49.

- ↑ Putterford 1994, pp. 62–63.

- ↑ Putterford 1994, pp. 70–71.

- ↑

- "Philip Lynott". Jim Fitzpatrick (official website).

- ↑ Putterford 1994, pp. 90–91.

- ↑ Putterford 1994, p. 114.

- ↑ Putterford 1994, p. 118.

- ↑ Putterford 1994, p. 228.

- ↑ Putterford 1994, p. 124.

- ↑ Putterford 1994, p. 103.

- ↑ Putterford 1994, p. 152.

- ↑ Putterford 1994, p. 128.

- ↑ Putterford 1994, p. 158.

- ↑ Putterford 1994, pp. 228–235.

- ↑ Putterford 1994, p. 245.

- ↑ Putterford 1994, pp. 248–250.

- 1 2 Putterford 1994, p. 169.

- ↑ Putterford 1994, p. 170.

- ↑ Greg Prato. "The Greedies – Music biography". Retrieved 20 December 2012.

- ↑ Byrne 2012, p. 79.

- ↑ Putterford 1994, pp. 186–187.

- ↑ Putterford 1994, p. 205.

- ↑ Putterford 1994, p. 204.

- ↑ Putterford 1994, p. 280.

- ↑ Putterford 1994, pp. 259–260.

- ↑ Putterford 1994, pp. 265–266.

- ↑ Putterford 1994, p. 277.

- ↑ Byrne 2012, pp. 145–48.

- ↑ Putterford 1994, p. 282.

- 1 2 3 "Farewell, Phil", Sounds, 11 January 1986, p. 3

- ↑ Wardlaw, Mark (20 August 2011). "10 Things You Didn't Know About Thin Lizzy's Phil Lynott". Classic Rock magazine. Retrieved 25 June 2015.

- ↑ Putterford 1994, p. 195.

- ↑ Putterford 1994, p. 198.

- ↑ Putterford 1994, p. 252.

- ↑ Ken Sweeney (26 July 2010). "Lynott son's joy as Phil's family recognise him". Irish Independent. Retrieved 26 July 2010.

- ↑ "Life After Lizzy". Irish Independent. 7 December 2013. Retrieved 9 December 2013.

- ↑ Putterford 1994, p. 196-197.

- ↑ Taylor, Paul (28 February 2011). "Phil Lynott's mother recalls exciting days in Manchester". Manchester Evening News. Retrieved 25 June 2015.

- ↑ Goddard, Simon (2013). Songs That Saved Your Life – The Art of The Smiths 1982–87 (revised edition). Titan Books. p. 392. ISBN 978-1-781-16259-0.

- ↑ Putterford 1994, p. 291.

- ↑ Putterford 1994, p. 292.

- ↑ Putterford 1994, pp. 296–297.

- 1 2 "Lynott's mum gives son's grave a kicking". Irish Examiner. 11 October 2012. Retrieved 25 June 2015.

- ↑ "Black Star Riders – All Hell Breaks Loose". Classic Rock magazine: 17–18. February 2013. Retrieved 25 June 2015.

- ↑ "Vibe for Philo". Irish Times. 31 Dec 2014. Retrieved 25 June 2015.

- ↑ "Vibe for Philo". Visit the Irish. Retrieved 25 June 2015.

- ↑ Putterford 1994, pp. 305–307.

- ↑ Thin Lizzy's Lynott back in town, BBC News/Northern Ireland, 20 August 2005. Retrieved 28 December 2007

- ↑ "Lynott's grave, St. Fintan's Cemetery". Findagrave.com. 1 January 2001. Retrieved 2011-07-17.

- ↑ "The Rocker: A Portrait of Phil Lynott". Amazon. Retrieved 14 December 2012.

- ↑ "Yellow Pearl : A Collection". AllMusic. Retrieved 25 June 2015.

- ↑ Henry McDonald (3 September 2012). "Phil Lynott's mother objects to Mitt Romney using Thin Lizzy's music". The Guardian. Retrieved 14 December 2012.

- ↑ Lyndsey Telford (14 September 2012). "Stop! Phil Lynott's widow orders Mitt Romney not to use Thin Lizzy music". The Independent. Retrieved 14 December 2012.

- ↑ "Picture of Phil Lynott playing a Rickenbacker 4001 bass". The Independent. Retrieved 14 December 2012.

- ↑ "Picture of Phil Lynott playing his Fender Precision bass with 'mirror' pickguard". The Guardian. Retrieved 14 December 2012.

Sources

External links

- Phil Lynott discography at Discogs