Pierre Laval

| Pierre Laval | |

|---|---|

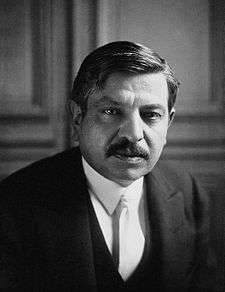

|

(1931) | |

| Prime Minister of France | |

|

In office 18 April 1942 – 20 August 1944 | |

| Preceded by | François Darlan |

| Succeeded by | Charles de Gaulle |

|

In office 11 July 1940 – 13 December 1940 | |

| Preceded by | Philippe Pétain |

| Succeeded by | Pierre Étienne Flandin |

|

In office 7 June 1935 – 24 January 1936 | |

| Preceded by | Fernand Bouisson |

| Succeeded by | Albert Sarraut |

|

In office 27 January 1931 – 20 February 1932 | |

| President |

Gaston Doumergue Paul Doumer |

| Preceded by | Théodore Steeg |

| Succeeded by | André Tardieu |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

28 June 1883 Châteldon, France |

| Died |

15 October 1945 (aged 62) Fresnes, France |

| Resting place | Montparnasse Cemetery[1] |

| Political party |

Socialist (1914–23) Independent (1923–45) |

| Religion | Roman Catholic |

Pierre Laval (French pronunciation: [pjɛʁ laval]; 28 June 1883 – 15 October 1945) was a French politician. During the time of the Third Republic, he served as Prime Minister of France from 27 January 1931 to 20 February 1932, and also headed another government from 7 June 1935 to 24 January 1936.

Laval began his career as a socialist, but over time drifted far to the right. Following France's surrender and armistice with Germany in 1940, he served in the Vichy Regime. He took a prominent role under Philippe Pétain, first as the vice-president of Vichy's Council of Ministers from 11 July 1940 to 13 December 1940, and later as the head of government from 18 April 1942 to 20 August 1944.

After the liberation of France in 1944, Laval was arrested by the French government under General Charles de Gaulle. In what some historians consider a flawed trial, Laval was found guilty of high treason, and after a thwarted suicide attempt, he was executed by firing squad.[2] His manifold political activities have left a complicated and controversial legacy, and there are more than a dozen biographies of him.

Early life

Laval was born 28 June 1883 at Châteldon, Puy-de-Dôme, in the northern part of Auvergne. His father worked in the village as a café proprietor, butcher and postman; he also owned a vineyard and horses. Laval was educated at the village school in Châteldon. At age 15, he was sent to a Paris lycée to study for his baccalauréat. Returning south to Lyon, he spent the next year reading for a degree in zoology.[3]

Laval joined the Socialists in 1903, when he was living in Saint-Étienne, 62 km southwest of Lyon.

"I was never a very orthodox socialist", he said in 1945, "by which I mean that I was never much of a Marxist. My socialism was much more a socialism of the heart than a doctrinal socialism... I was much more interested in men, their jobs, their misfortunes and their conflicts than in the digressions of the great German pontiff."[4]

Laval returned to Paris in 1907 at the age of 24. He was called up for military service and, after serving in the ranks, was discharged for varicose veins. In April 1913 he said: "Barrack-based armies are incapable of the slightest effort, because they are badly-trained and, above all, badly commanded." He favoured abolition of the army and replacement by a citizens' militia.[5]

During this period, Laval became familiar with the left-wing doctrines of Georges Sorel and Hubert Lagardelle. In 1909, he turned to the law.

Marriage and family

Shortly after becoming a member of the Paris bar, he married the daughter of a Dr Joseph Claussat and set up a home in Paris with his new wife. Their only child, a daughter called Josée Laval, was born in 1911. Josée married René de Chambrun, whose uncle, Nicholas Longworth III, married Alice Roosevelt, daughter of United States President Theodore Roosevelt. Although Laval's wife came from a political family, she never participated in politics. Laval was generally considered to be devoted to his family.[6]

Before the war

The years before the First World War were characterised by labour unrest, and Laval defended strikers, trade unionists, and left-wing agitators against government attempts to prosecute them. At a trade union conference, Laval said:

I am a comrade among comrades, a worker among workers. I am not one of those lawyers who are mindful of their bourgeois origin even when attempting to deny it. I am not one of those high-brow attorneys who engage in academic controversies and pose as intellectuals. I am proud to be what I am. A lawyer in the service of manual laborers who are my comrades, a worker like them, I am their brother. Comrades, I am a manual lawyer.[7]

During the First World War

Socialist Deputy for the Seine

In April 1914, as fear of war swept the nation, the Socialists and Radicals geared up their electoral campaign in defence of peace. Their leaders were Jean Jaurès and Joseph Caillaux. The Bloc des Gauches (Leftist Bloc) denounced the law passed in July 1913 extending compulsory military service from two to three years. The Confédération générale du travail trade union sought Laval as Socialist candidate for the Seine, the district comprising Paris and its suburbs. He won. The Radicals, with the support of Socialists, held the majority in the French Chamber of Deputies. Together they hoped to avert war. The assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria on 28 June 1914 and of Jaurès on 31 July 1914 shattered those hopes. Laval's brother, Jean, died in the first months of the war.

Laval and 2,000 others were listed by the military in the Carnet B, a compilation of potentially subversive elements who might hinder mobilisation. In the name of national unity, Minister of the Interior Jean-Louis Malvy, despite pressure from chiefs of staff, refused to have anyone apprehended. Laval remained true to his pacifist convictions during the war. In December 1915, Jean Longuet, grandson of Karl Marx, proposed to Socialist parliamentarians that they communicate with socialists of other states, hoping to press governments into a negotiated peace. Laval signed on, but the motion was defeated.

With France's resources geared for war, goods were scarce or overpriced. On 30 January 1917, in the National Assembly Laval called upon the Supply Minister Édouard Herriot to deal with the inadequate coal supply in Paris. When Herriot said, "If I could, I would unload the barges myself", Laval retorted "Do not add ridicule to ineptitude."[8] The words delighted the assembly and attracted the attention of George Clemenceau, but left the relationship between Laval and Herriot permanently strained.

Stockholm, the "polar star"

Laval scorned the conduct of the war and the poor supply of troops in the field. When mutinies broke out after General Robert Nivelle's offensive of April 1917 at Chemin des Dames, he spoke in defence of the mutineers. When Marcel Cachin and Marius Moutet returned from St. Petersburg in June 1917 with the invitation to a socialist convention in Stockholm, Laval saw a chance for peace. In an address to the Assembly, he urged the chamber to allow a delegation to go: "Yes, Stockholm, in response to the call of the Russian Revolution.... Yes, Stockholm, for peace.... Yes, Stockholm the polar star." The request was denied.

The hope of peace in spring 1917 was overwhelmed by discovery of traitors, some real, some imagined, as with Malvy. Because he had refused to arrest Frenchmen on the Carnet B, Malvy became a suspect. Laval's "Stockholm, étoile polaire" speech had not been forgotten. Many of Laval's acquaintances, the publishers of the anarchist Bonnet rouge, and other pacifists were arrested or interrogated. Though Laval frequented pacifist circles – it was said that he was acquainted with Leon Trotsky – the authorities did not pursue him. His status as a deputy, his caution, and his friendships protected him. In November 1917, Clemenceau offered him a post in government, but the Socialist Party had by then refused to enter any government. Laval toed the party line, but he questioned the wisdom of such a policy in a meeting of the Socialist members of parliament.

Initial postwar career

From Socialist to Independent

In 1919 a conservative wave swept the Bloc National into control. Laval was not re-elected. The Socialists' record of pacifism, their opposition to Clemenceau, and anxiety arising from the excesses of the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia contributed to their defeat.

The General Confederation of Labour (CGT), with 2,400,000 members, launched a general strike in 1920, which petered out as thousands of workers were laid off. In response, the government sought to dissolve the CGT. Laval, with Joseph Paul-Boncour as chief counsel, defended the union's leaders, saving the union by appealing to the ministers Théodore Steeg (interior) and Auguste Isaac (commerce and industry).

Laval's relations with the Socialist Party drew to an end. The last years with the Socialist caucus in the chamber combined with the party's disciplinary policies eroded Laval's attachment to the cause. With the Bolshevik victory in Russia the party was changing; at the Congress of Tours in December 1920, the Socialists split into two ideological components: the French Communist Party (SFIC later PCF), inspired by Moscow, and the more moderate French Section of the Workers' International (SFIO). Laval let his membership lapse, not taking sides as the two factions battled over the legacy of Jean Jaurès.

Mayor of Aubervilliers

In 1923 Aubervilliers in northern Paris needed a mayor. As a former deputy of the constituency, Laval was an obvious candidate. To be eligible for election, Laval bought farmland, Les Bergeries. Few were aware of his defection from the Socialists. Laval was also asked by the local SFIO and Communist Party to head their lists. Laval chose to run under his own list, of former socialists he convinced to leave the party and work for him. This was an independent Socialist Party of sorts that existed only in Aubervilliers. In a four-way race, Laval won in the second round. He served as mayor of Aubervilliers until just before his death.

Laval won over those he defeated by cultivating personal contacts. He developed a network among the humble and the well-to-do in Aubervilliers, and with mayors of neighbouring towns. He was the only independent politician in the suburb. He avoided entering the ideological war between socialists and communists.

Independent Deputy for the Seine

In the 1924 legislative elections, the SFIO and the Radicals formed a national coalition known as the Cartel des Gauches. Laval headed a list of independent socialists in the Seine. The cartel won and Laval regained a seat in the National Assembly. His first act was to bring back Joseph Caillaux, former Prime Minister, Cabinet member and member of the National Assembly and once the star of the Radical Party. Clemenceau had had Caillaux arrested toward the end of the war for collusion with the enemy. He spent two years in prison and lost his civic rights. Laval stood for Caillaux's pardon and won. Caillaux became an influential patron.

As a member of the government

Minister and senator

Laval's reward for support of the cartel was appointment as Minister of Public Works in the government of Paul Painlevé in April 1925. Six months later, the government collapsed. Laval from then on belonged to the club of former ministers from which new ministers were drawn. Between 1925 and 1926 Laval participated three more times in governments of Aristide Briand, once as under-secretary to the premier and twice as Minister of Justice (garde des sceaux). When he first became Minister of Justice, Laval abandoned his law practice to avoid conflict of interest.

Laval's momentum was frozen after 1926 through a reshuffling of the cartel majority orchestrated by the Radical-Socialist mayor and deputy of Lyon, Édouard Herriot. Founded in 1901, the Radical Party became the hinge faction of the Third Republic. Its support or defection often meant survival or collapse of governments. Through this latest swing, Laval was excluded from the direction of France for four years. Author Gaston Jacquemin suggested that Laval chose not to partake in a Herriot government, which he judged incapable of handling the financial crisis. 1926 marked the definitive break between Laval and the left, but he maintained friends on the left.

In 1927 Laval was elected Senator for the Seine, withdrawing from and placing himself above the political battles for majorities in the National Assembly. He longed for a constitutional reform to strengthen the executive branch and eliminate political instability, the flaw of the Third Republic.

On 2 March 1930 Laval returned as Minister of Labour in the second André Tardieu government. Tardieu and Laval knew each other from the days of Clemenceau, which developed into mutual appreciation. Tardieu needed men he could trust: his previous government had collapsed a little over a week earlier because of the defection of the minister of Labor, Louis Loucheur. But, when the Radical Socialist Camille Chautemps failed to form a viable government, Tardieu was called back.

Personal investments

From 1927 to 1930, Laval began to accumulate a sizeable personal fortune; after the war his wealth resulted in charges that he had used his political position to line his own pockets. "I have always thought", he wrote to the examining magistrate on 11 September 1945, "that a soundly based material independence, if not indispensable, gives those statesmen who possess it a much greater political independence." Until 1927 his principal source of income had been his fees as a lawyer and in that year they totalled 113,350 francs, according to his income tax returns. Between August 1927 and June 1930, he undertook large-scale investments in various enterprises, totalling 51 million francs. Not all this money was his own; it came from a group of financiers who had the backing of an investment trust, the Union Syndicale et Financière and two banks, the Comptoir Lyon Allemand and the Banque Nationale de Crédit.[9]

Two of the investments which Laval and his backers acquired were provincial newspapers, Le Moniteur du Puy-de-Dôme and its associated printing works at Clermont-Ferrand, and the Lyon Républicain. The circulation of the Moniteur stood at 27,000 in 1926 before Laval took it over. By 1933, it had more than doubled to 58,250. Thereafter circulation declined and never surpassed this peak. Profits varied, but during the seventeen years of his control, Laval earned some 39 million francs in income from the paper and the printing works combined. The renewed plant was valued at 50 million francs, which led the high court expert in 1945 to say with some justification that it had been "an excellent deal for him."[10]

Minister of Labour and Social Insurance

More than 150,000 textile workers were on strike, and violence was feared. As Minister of Public Works in 1925, Laval had ended the strike of mine workers. Tardieu hoped he could do the same as Minister of Labour. The conflict was settled without bloodshed. Socialist politician Léon Blum, never one of Laval's allies, conceded that Laval's "intervention was skillful, opportune and decisive."[11]

Social insurance had been on the agenda for ten years. It had passed the Chamber of Deputies, but not the Senate, in 1928. Tardieu gave Laval until May Day to get the project through. The date was chosen to stifle the agitation of Labour Day. Laval's first effort went into clarifying the muddled collection of texts. He then consulted employer and labour organisations. Laval had to reconcile the divergent views of Chamber and Senate. "Had it not been for Laval's unwearying patience", Laval's associate Tissier wrote, "an agreement would never have been achieved",[12] In two months Laval presented the Assembly a text which overcame its original failure. It met the financial constraints, reduced the control of the government, and preserved the choice of doctors and their billing freedom. The Chamber and the Senate passed the law with an overwhelming majority.

When the bill had passed its final stages, Tardieu described his Minister of Labour as "displaying at every moment of the discussion as much tenacity as restraint and ingenuity."[13]

First Laval government

Tardieu's government ultimately proved unable to weather the Oustric Affair. After the failure of the Oustric Bank, it appeared that members of the government had improper ties to it. The scandal involved Minister of Justice Raoul Péret, and Under-Secretaries Henri Falcoz and Eugène Lautier. Though Tardieu was not involved, on 4 December 1930, he lost his majority in the Senate. President Gaston Doumergue called on Louis Barthou to form a government, but Barthou failed. Doumergue turned to Laval, who fared no better. The following month the government formed by Théodore Steeg floundered. Doumergue renewed his offer to Laval. On 27 January 1931 Laval successfully formed his first government.

In the words of Léon Blum, the Socialist opposition was amazed and disappointed that the ghost of Tardieu's government reappeared within a few weeks of being defeated with Laval at its head, "like a night bird surprised by the light." Laval's nomination as premier led to speculation that Tardieu, the new agriculture minister, held the real power in the Laval Government. Although Laval thought highly of Tardieu and Briand, and applied policies in line with theirs, Laval was not Tardieu's mouthpiece. Ministers who formed the Laval government were in great part those who had formed Tardieu governments but that was a function of the composite majority Laval could find at the National Assembly. Raymond Poincaré, Aristide Briand and Tardieu before him had offered ministerial posts to Herriot's Radicals, but to no avail.

Besides Briand, André Maginot, Pierre-Étienne Flandin, Paul Reynaud, Laval brought in as his advisors, friends such as Maurice Foulon from Aubervilliers, and Pierre Cathala, whom he knew from his days in Bayonne and who had worked in Laval's Labour ministry. Cathala began as Under-Secretary of the Interior and was appointed as Minister of the Interior in January 1932. Blaise Diagne of Senegal, the first African deputy, had been elected to the National Assembly at the same time as Laval in 1914. Laval invited Diagne to join his cabinet as under-secretary to the colonies; he was the first Black African appointed to a cabinet position in a French government. Laval also called on financial experts such as Jacques Rueff, Charles Rist and Adéodat Boissard. André François-Poncet was appointed as under-secretary to the premier and then as ambassador to Germany. Laval's government included an economist, Claude-Joseph Gignoux, when economists in government service were rare.

France in 1931 was unaffected by the world economic crisis. Laval declared on embarking for the United States on 16 October 1931, "France remained healthy thanks to work and savings." Agriculture, small industry, and protectionism were the bases of France's economy. With a conservative policy of contained wages and limited social services, France had accumulated the largest gold reserves in the world after the United States. France reaped the benefit of devaluation of the franc orchestrated by Poincaré, which made French products competitive on the world market. In the whole of France, 12,000 people were recorded as unemployed.

Laval and his cabinet considered the economy and gold reserves as means to diplomatic ends. Laval left to visit London, Berlin and Washington. He attended conferences on the world crisis, war reparations and debt, disarmament, and the gold standard.

Role in 1931 Austrian financial crisis

In 1931, Austria underwent a banking crisis when its largest bank, the Creditanstalt, was revealed to be nearly bankrupt, threatening a worldwide financial crisis. World leaders began negotiating the terms for an international loan to Austria's central government to sustain its financial system; however, Laval blocked the proposed package for nationalistic reasons. He demanded that France receive a series of diplomatic concessions in exchange for its support, including renunciation of a prospective German-Austrian customs union. This proved to be fatal for the negotiations, which ultimately fell through.[14][15] As a result, the Creditanstalt declared bankruptcy on 11 May 1931, precipitating a crisis that quickly spread to other nations. Within four days, bank runs in Budapest were underway, and the bank failures began spreading to Germany and Britain, among others.[16]

Hoover Moratorium (20 June 1931)

The Hoover Moratorium of 1931, a proposal made by American President Herbert Hoover to freeze all intergovernmental debt for a one-year period, was, according to author and political advisor McGeorge Bundy, "the most significant action taken by an American president for Europe since Woodrow Wilson's administration." The United States had enormous stakes in Germany: long-term German borrowers owed the United States private sector more than $1.25 billion; the short-term debt neared $1 billion. By comparison, the entire United States national income in 1931 was just $54 billion. To put it into perspective, authors Walter Lippmann and William O. Scroggs stated in The United States in World Affairs, An Account of American Foreign Relations, that "the American stake in Germany's government and private obligations was equal to half that of all the rest of the world combined."

The proposed moratorium would also benefit Great Britain's investment in Germany's private sector, making more likely the repayment of those loans while the public indebtedness was frozen. It was in Hoover's interest to offer aid to an ailing British economy in the light of the indebtedness of Great Britain to the United States. France, on the other hand, had a relatively small stake in Germany's private debt but a huge interest in German reparations; and payment to France would be compromised under Hoover's moratorium.

The scheme was further complicated by ill timing, perceived collusion among the US, Great Britain and Germany, and the fact that it constituted a breach of the Young Plan. Such breach could only be approved in France by the National Assembly; the survival of the Laval Government rested on the legislative body's approval of the moratorium. Seventeen days elapsed between the proposal and the vote of confidence of the French legislators. That delay was blamed for the lack of success of the Hoover Moratorium. The US Congress did not approve it until December 1931.

In support of the Hoover Moratorium Laval undertook a year of personal and direct diplomacy by which he traveled to London, Berlin and the United States. While he were considerable domestic achievements to his name, his international efforts were short on results. British Premier Ramsay MacDonald and Foreign Secretary Arthur Anderson— preoccupied by internal political divisions and the collapse of the pound sterling— were unable to help. German Chancellor Heinrich Brüning and Foreign Minister Julius Curtius, both eager for Franco-German reconciliation, were under siege on all sides: they faced a very weak economy which made meeting government payroll a weekly miracle. Private bankruptcies and constant layoffs had the communists on a short fuse. On the other end of the political spectrum, the German Army was spying on the Brüning cabinet and feeding information to the Stahlhelm, Bund der Frontsoldaten and the National Socialists, effectively freezing any overtures towards France.

In the United States the conference between Hoover and Laval was an exercise in mutual frustration. Hoover's plan for a reduced military had been rebuffed—albeit gently. A solution to the Danzig corridor had been retracted. The concept of introducing silver standard for the countries that went off the gold standard was disregarded as a frivolous proposal by Laval and Albert-Buisson. Hoover thought it might have helped "Mexico, India, China and South America", but Laval dismissed the silver solution as an inflationary proposition, adding that "it was cheaper to inflate paper."[17]

Laval did not get a security pact, without which the French would never consider disarmament, nor did he obtain an endorsement for the political moratorium. The promise to match any reduction of German reparations with a decrease of the French debt was not put in the communiqué. The joint statement declared the attachment of France and the United States to the gold standard. The two governments also agreed that the Banque de France and the Federal Reserve would consult each other before transfers of gold. This was welcome news after the run on American gold in the preceding weeks. In light of the financial crisis, the leaders agreed to review the economic situation in Germany before the Hoover moratorium had run its course.

These were meagre political results. The Hoover–Laval encounter, however, had other effects: it made Laval more widely known and raised his standing in the United States and France. The American and French press were smitten. His optimism was such a contrast to his grim-sounding international contemporaries that in Time magazine named him as the 1931 Man of the Year.[18] An honour never bestowed before on a Frenchman. He followed Mohandas K. Gandhi and preceded Franklin D. Roosevelt in receiving the honour.

1934–36

The second Cartel des Gauches (Left-Wing Cartel) was driven from power by the riots of 6 February 1934, staged by fascist, monarchist, and other far-right groups. (These groups had contacts with some conservative politicians, among whom were Laval and Marshal Philippe Pétain.) Laval became Minister of Colonies in the new right-wing government of Gaston Doumergue. In October, Foreign Minister Louis Barthou was assassinated; Laval succeeded him, holding that office until 1936.

At this time, Laval was opposed to Germany, the "hereditary enemy" of France, and he pursued anti-German alliances. He met with Mussolini in Rome, and they signed the Franco-Italian Agreement of 1935 on 4 January. The agreement ceded parts of French Somaliland to Italy and allowing her a free hand in Abyssinia, in exchange for support against any German aggression.[19] Laval denied that he gave Mussolini a free hand in Abyssinia, he even wrote to Il Duce on the subject.[20] In April 1935, Laval persuaded Italy and Great Britain to join France in the Stresa Front against German ambitions in Austria. On 2 May 1935, he likewise signed the Franco-Soviet Treaty of Mutual Assistance.[21]

Laval's primary aim during the build-up to the Italo-Abyssinian War was to retain Italy as an anti-German power and not to drive her into Germany's hands by adopting a hostile attitude to an invasion of Abyssinia.[22] According to the English historian Correlli Barnett, in Laval's view "all that really mattered was Nazi Germany. His eyes were on the demilitarised zone of the Rhineland; his thoughts on the Locarno guarantees. To estrange Italy, one of the Locarno powers, over such a question as Abyssinia did not appeal to Laval's Auvergnat peasant mind".[23][24] In June 1935, he became Prime Minister as well. In October 1935, Laval and British foreign minister Samuel Hoare proposed a realpolitik solution to the Abyssinia Crisis. When leaked to the media in December, the Hoare–Laval Pact was widely denounced as appeasement to Mussolini. Laval was forced to resign on 22 January 1936, and was driven completely out of ministerial politics. The victory of the Popular Front in 1936 meant that Laval had a left-wing government as a target for his media.

Under Vichy France

Formation of the Vichy Government

During the Phoney War, Laval's attitude towards the conflict reflected a cautious ambivalence. He was on record as saying that although the war could have been avoided by diplomatic means, it was now up to the government to prosecute it with the utmost vigour.[25]

On 9 June 1940, the Germans were advancing on a front of more than 250 kilometres (160 mi) in length across the entire width of France. As far as General Maxime Weygand was concerned, "if the Germans crossed the Seine and the Marne, it was the end."[26] Simultaneously, Marshal Philippe Pétain was increasing the pressure upon Prime Minister Paul Reynaud to call for an armistice. During this time Laval was in Châteldon. On 10 June, in view of the German advance, the government left Paris for Tours. Weygand had informed Reynaud: "the final rupture of our lines may take place at any time." If that happened "our forces would continue to fight until their strength and resources were extinguished. But their disintegration would be no more than a matter of time."[27] Weygand had avoided using the word armistice, but it was on the minds of all those involved. Only Reynaud was in opposition.

During this time Laval had left Châteldon for Bordeaux, where his daughter nearly convinced him of the necessity of going to the United States. Instead, it was reported that he was sending "messengers and messengers" to Pétain.[28]

As the Germans occupied Paris, Pétain was asked to form a new government. To everyone's surprise, he produced a list of his ministers, convincing proof that he had been expecting the president's summons and he had prepared for it.[29] Laval's name was on the list as Minister of Justice. When informed of his proposed appointment, Laval's temper and ambitions became apparent as he ferociously demanded of Pétain, despite the objections of more experienced men of government, that he be made Minister of Foreign Affairs. Laval realised that only through this position could he effect a reversal of alliances and bring himself to favour with Nazi Germany, the military power he viewed as the inevitable victor. In the face of Laval's wrath, dissenting voices acquiesced and Laval became Minister of Foreign Affairs.[30] One result of these events was that Laval was later able to claim that he was not part of the government that requested the armistice. His name did not appear in the chronicles of events until June when he began to assume a more active role in criticising the government's decision to leave France for North Africa.

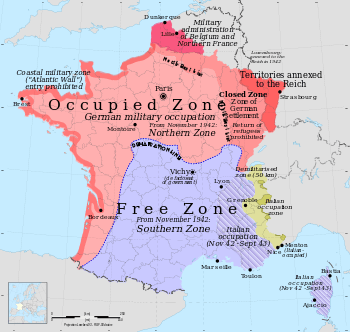

Although the final terms of the armistice were harsh, the French colonial empire was left untouched and the French government was allowed to administer the occupied and unoccupied zones. The concept of "collaboration" was written into the Armistice Convention, before Laval joined the government. The French representatives who affixed their signatures to the text accepted the term.

Article III. In the occupied areas of France, the German Reich is to exercise all the rights of an occupying power. The French government promises to facilitate by all possible means the regulations relative to the exercise of this right, and to carry out these regulations with the participation of the French administration. The French government will immediately order all the French authorities and administrative services in the occupied zone to follow the regulations of the German military authorities and to collaborate with the latter in a correct manner.

Laval in the Vichy government, 1940–41

By this time, Laval now openly sympathized with fascism. He was convinced that Germany would win the war, and felt France needed to emulate its totalitarian regime as much as possible. To that end, when he was included in the cabinet as minister of state, Laval set about with the work for which he would be remembered: dismantling the Third Republic and its democracy and taking up the fascist cause.[31]

In October 1940, Laval understood collaboration more or less in the same sense as Pétain. For both, to collaborate meant to give up the least possible to get the most.[32] Laval, in his role of go-between, was forced to be in constant touch with the German authorities, to shift ground, to be wily, to plan ahead. All this, under the circumstances, drew more attention to him than to the Marshal and made him appear to many Frenchmen as "the agent of collaboration"; to others, he was "the Germans' man".[33]

The meetings between Pétain and Adolf Hitler, and between Laval and Hitler, are often used to show that collaboration with the Nazis. In fact Montoire (24–26 October 1940) was a disappointment to both sides. Hitler wanted France to declare war on Britain, and the French wanted improved relations with her conqueror. Neither happened. Virtually the only concession the French obtained was the 'Berlin protocol' of 16 November 1940, which provided release of certain categories of French prisoners of war.

In November 1940, Laval took a number of pro-German decisions of his own, without consulting with colleagues. The most notorious examples concerned turning the RTB Bor copper mines and the Belgian gold reserves over to Nazi control. After the war, Laval's justification, apart from a denial that he acted unilaterally, was that Vichy were powerless to prevent the Germans from gaining something they were clearly so eager to obtain.[34]

Laval's actions were a factor in his dismissal on 13 December 1940. Pétain asked all the ministers to sign a collective letter of resignation during a full cabinet meeting. Laval did so thinking it was a device to get rid of M. Belin, the Minister of Labor. He was therefore stunned when the Marshal announced, "the resignations of MM. Laval and Ripert are accepted."[35] That evening, Laval was arrested and driven by the police to his home in Châteldon. The following day, Pétain announced his decision to remove Laval from the government. The reason for Laval's dismissal lies in a fundamental incompatibility with Pétain. Laval's methods of working appeared slovenly to Petain's precise military mind, and he showed a marked lack of deference, instanced by a habit of blowing cigarette smoke in Pétain's face. By doing so he aroused Pétain's irritation and the anger of the entire cabinet.[36]

On 27 August 1941, several top Vichyites including Laval attended a review of the Légion des Volontaires Français (LVF), a collaborationist militia. Paul Collette, a disgruntled ex-member of the Croix-de-Feu, attacked the reviewing stand; he shot Laval (and also Marcel Déat, another prominent collaborationist), slightly wounding him. Laval soon recovered from the injury.

Return to power, 1942

Laval returned to power in April 1942. Laval had been in power for a mere two months when he was faced with the decision of providing forced workers to Germany. The Reich was short of skilled labour due to its need for troop replacements on the Russian front. Unlike other occupied countries, France was technically protected by the armistice, and its workers could not be simply rounded up for transportation. In the occupied zone, the Germans used intimidation and control of raw materials to create unemployment and thus reasons for French labourers to volunteer to work in Germany. Nazi officials demanded Laval send more than 300,000 skilled workers immediately to factories in Germany. Laval delayed making a counter-offer of one worker in return for one French POW. The proposal was sent to Hitler, a compromise was reached: one prisoner of war to be repatriated for every three workers arriving in Germany.[37]

Laval's precise role in the deportation of Jews has been hotly debated by both his accusers and defenders. When ordered to have all Jews in France rounded up to be transported to German-occupied Poland, Laval negotiated a compromise. He allowed only those Jews who were not French citizens to be forfeited to German control. It was estimated that by the end of the war, the Germans had killed 90 percent of the Jewish population in other occupied countries, but in France fifty per cent of the pre-war French and foreign Jewish population, with perhaps ninety per cent of the purely French Jewish population still remaining alive.[38] Laval went beyond the orders given to him by the Germans, as he included Jewish children under 16 in the deportations. The Germans had given him permission to spare children under 16. In his book Churches and the Holocaust, Mordecai Paldiel claims that when Protestant leader Martin Boegner visited Laval to remonstrate. Laval claimed that he had ordered children to be deported along with their parents because families should not be separated and "children should remain with their parents".[39] According to Paldiel, when Boegner argued that the children would almost certainly die, Laval replied "not one [Jewish child] must remain in France". Yet, Sarah Fishman (in a reliably sourced book, but lacking citations) claims that Laval also attempted to prevent Jewish children gaining visas to America, arranged by the American Friends Service Committee. Fishman asserts Laval was not so much committed to expelling Jewish children from France, as making sure they reached Nazi camps.[40]

More and more the insoluble dilemma of collaboration faced Laval and his chief of staff, Jean Jardin. Laval had to maintain Vichy's authority to prevent Germany from installing a Quisling Government made up of French Nazis such as Jacques Doriot.[41]

Leader of the Milice, 1943–45

In 1943, Laval became the nominal leader of the newly created Milice, though its operational leader was Secretary General Joseph Darnand.[42]

When Operation Torch, the landings of Allied forces in North Africa began, Germany occupied all of France. Hitler continued to ask whether the French government was prepared to fight at his side, requiring Vichy to declare war against Britain. Laval and Pétain agreed to maintain a firm refusal. During this time and the Normandy landings in 1944, Laval was in a struggle against ultra-collaborationist ministers.

In a speech broadcast on the Normandy landings' D-day, he appealed to the nation:

You are not in the war. You must not take part in the fighting. If you do not observe this rule, if you show proof of indiscipline, you will provoke reprisals the harshness of which the government would be powerless to moderate. You would suffer, both physically and materially, and you would add to your country's misfortunes. You will refuse to heed the insidious appeals, which will be addressed to you. Those who ask you to stop work or invite you to revolt are the enemies of our country. You will refuse to aggravate the foreign war on our soil with the horror of civil war.... At this moment fraught with drama, when the war has been carried on to our territory, show by your worthy and disciplined attitude that you are thinking of France and only of her."[43]

A few months later, he was arrested by the Germans and transported to Belfort. In view of the speed of the Allied advance, on 7 September 1944 what was left of the Vichy government was moved from Belfort to the Sigmaringen enclave in Germany. Pétain took residence at the Hohenzollern castle in Sigmaringen. At first Laval also resided in this castle. In January 1945 Laval was assigned to the Stauffenberg castle of Ernst Juenger/Wilflingen 12 km outside the Sigmaringen enclave. By April 1945 US General George S. Patton's army approached Sigmaringen, so the Vichy ministers were forced to seek their own refuge. Laval received permission to enter Spain and was flown to Barcelona by a Luftwaffe plane. However, 90 days later, De Gaulle pressured Spain to expel Laval. The same Luftwaffe plane that flew him to Spain flew him to the American-occupied zone of Austria. The American authorities immediately arrested Laval and his wife and turned them over to the Free French. They were flown to Paris to be imprisoned at Fresnes, Val-de-Marne. Madame Laval was later released; Pierre Laval remained in prison to be tried as a traitor.[44]

Prior to his arrest, Laval had planned to move to Sintra, Portugal, where a house had been leased for him.[45][46]

Trial and execution

Two trials were to be held. Although it had its faults, the Pétain trial permitted the presentation and examination of a vast amount of pertinent material. Scholars including Robert Paxton and Geoffrey Warner believe that Laval's trial demonstrated the inadequacies of the judicial system and the poisonous political atmosphere of that purge-trial era.[47][48] During his imprisonment pending the verdict of his treason trial, Laval wrote his only book, his posthumously published Diary (1948). His daughter, Josée de Chambrun, smuggled it out of the prison page by page.[49]

Laval firmly believed that he would be able to convince his fellow-countrymen that he had been acting in their best interests all along. "Father-in-law wants a big trial which will illuminate everything", René de Chambrun told Laval's lawyers: "If he is given time to prepare his defence, if he is allowed to speak, to call witnesses and to obtain from abroad the information and documents which he needs, he will confound his accusers."[50] "Do you want me to tell you the set-up?" Laval asked one of his lawyers on 4 August. "There will be no pre-trial hearings and no trial. I will be condemned – and got rid of – before the elections."[51]

Laval's trial began at 1:30 pm on Thursday, 4 October 1945. He was charged with plotting against the security of the State and intelligence (collaboration) with the enemy. He had three defence lawyers (Jaques Baraduc, Albert Naud, and Yves-Frédéric Jaffré). None of his lawyers had ever met him before. He saw most of Jaffré, who sat with him, talked, listened and took down notes that he wanted to dictate. Baraduc, who quickly became convinced of Laval's innocence, kept contact with the Chambruns and at first shared their conviction that Laval would be acquitted or at most receive a sentence of temporary exile. Naud, who had been a member of the Resistance, believed Laval to be guilty and urged him to plead that he had made grave errors but had acted under constraint. Laval would not listen to him; he was convinced that he was innocent and could prove it. "He acted", said Naud, "as if his career, not his life, was at stake."[52]

All three of his lawyers declined to be in court to hear the reading of the formal charges, saying "We fear that the haste which has been employed to open the hearings is inspired, not by judicial preoccupations, but motivated by political considerations." In lieu of attending the hearing, they sent letters stating the shortcomings and asked to be discharged as counsel.[53] The court carried on without them. The president of the court, Pierre Mongibeaux, announced the trial had to be completed before the general election scheduled for 21 October.[54] Mongibeaux and Mornet, the public prosecutor, were unable to control constant hostile outbursts from the jury. These occurred as increasingly heated exchanges between Mongibeaux and Laval became louder and louder. On the third day, Laval's three lawyers were with him as the President of the Bar Association had advised them to resume their duties.[55]

After the adjournment, Mongibeaux announced that the part of the interrogation dealing with the charge of plotting against the security of the state was concluded. To the charge of collaboration Laval replied, "Monsieur le Président the insulting way in which you questioned me earlier and the demonstrations in which some members of the jury indulged show me that I may be the victim of a judicial crime. I do not want to be an accomplice; I prefer to remain silent." Mongibeaux called the first of the prosecution witnesses, but they had not expected to give evidence so soon and none were present. Mongibeaux adjourned the hearing for the second time so that they could be located. When the court reassembled half an hour later, Laval was no longer in his place.[56]

Although Pierre-Henri Teitgen, the Minister of Justice in Charles de Gaulle's cabinet, personally appealed to Laval's lawyers to have him attend the hearings, he declined to do so. Teitgen freely confirmed the conduct of Mongibeaux and Mornet, professing he was unable to do anything to curb them. A sentence of death was handed down in Laval's absence. His lawyers were refused a re-trial.[57]

The execution was fixed for the morning of 15 October. Laval attempted to cheat the firing squad by taking poison from a phial stitched inside the lining of his jacket. He did not intend, he explained in a suicide note, that French soldiers should become accomplices in a "judicial crime". The poison, however, was so old that it was ineffective, and repeated stomach-pumpings revived Laval.[58] Laval requested that his lawyers witness his execution. He was shot shouting "Vive la France!" Shouts of "Murderers!" and "Long live Laval!" were apparently heard from the prison.[59] Laval's widow declared: "It is not the French way to try a man without letting him speak", she told an English newspaper, "That's the way he always fought against – the German way."[60]

His corpse was initially buried in an unmarked grave in the Thiais cemetery, until it was buried in the Chambrun family mausoleum at the Montparnasse Cemetery in November.[1][61]

His daughter, Josée Laval, wrote a letter to Churchill in 1948, suggesting the firing squad who killed her father "wore British uniforms".[62][63][64] The letter was published in the June 1949 issue of Human Events, an American conservative newspaper.[62][63][64]

The High Court, which functioned until 1949, judged 108 cases; it pronounced eight death penalties, including one for an elderly Pétain, whose appeal failed. Only three of the death penalties were carried out: Pierre Laval; Fernand de Brinon, Vichy's Ambassador in Paris to the German authorities; and Joseph Darnand, head of the Milice.[65]

Governments

Laval's First Ministry, 27 January 1931 – 14 January 1932

- Pierre Laval – President of the Council and Minister of the Interior

- Léon Bérard – Vice-President of the Council and Minister of Justice

- Aristide Briand – Minister of Foreign Affairs

- André Maginot – Minister of War

- Charles Dumont – Minister of Marine

- Jacques-Louis Dumesnil – Minister of Air

- Mario Roustan – Minister of Public Instruction and Fine Arts

- Pierre Étienne Flandin – Minister of Finance

- François Piétri – Minister of Budget

- Maurice Deligne – Minister of Public Works

- Louis Rollin – Minister of Commerce and Industry

- André Tardieu – Minister of Agriculture

- Charles de Chappedelaine – Minister of Merchant Marine

- Auguste Champetier de Ribes – Minister of Pensions

- Adolphe Landry – Minister of Labour and Social Security Provisions

- Camille Blaisot – Minister of Public Health

- Charles Guernier – Minister of Posts, Telegraphs, and Telephones

- Paul Reynaud – Minister of Colonies

Changes

A few changes after Aristide Briand's retirement and the death of André Maginot on 7 January 1932:

- War: André Tardieu

- Interieur: Pierre Cathala

- Agriculture: Achille Fould

- André François-Poncet upon becoming ambassador to Germany was replaced by C.J. Gignoux.

Laval's Second Ministry, 14 January – 20 February 1932

- Pierre Laval – President of the Council and Minister of Foreign Affairs

- André Tardieu – Minister of War

- Pierre Cathala – Minister of the Interior

- Pierre-Étienne Flandin – Minister of Finance

- François Piétri – Minister of Budget

- Adolphe Landry – Minister of Labour and Social Security Provisions

- Léon Bérard – Minister of Justice

- Charles Dumont – Minister of Marine

- Louis de Chappedelaine – Minister of Merchant Marine

- Jacques-Louis Dumesnil – Minister of Air

- Mario Roustan – Minister of Public Instruction and Fine Arts

- Auguste Champetier de Ribes – Minister of Pensions

- Achille Fould – Minister of Agriculture

- Paul Reynaud – Minister of Colonies

- Maurice Deligne – Minister of Public Works

- Camille Blaisot – Minister of Public Health

- Charles Guernier – Minister of Posts, Telegraphs, and Telephones

- Louis Rollin – Minister of Commerce and Industry

Laval's Third Ministry, 7 June 1935 – 24 January 1936

- Pierre Laval – President of the Council and Minister of Foreign Affairs

- Jean Fabry – Minister of War

- Joseph Paganon – Minister of the Interior

- Marcel Régnier – Minister of Finance

- Ludovic-Oscar Frossard – Minister of Labour

- Léon Bérard – Minister of Justice

- François Piétri – Minister of Marine

- Mario Roustan – Minister of Merchant Marine

- Victor Denain – Minister of Air

- Philippe Marcombes – Minister of National Education

- Henri Maupoil – Minister of Pensions

- Pierre Cathala – Minister of Agriculture

- Louis Rollin – Minister of Colonies

- Laurent Eynac – Minister of Public Works

- Ernest Lafont – Minister of Public Health and Physical Education

- Georges Mandel – Minister of Posts, Telegraphs, and Telephones

- Georges Bonnet – Minister of Commerce and Industry

- Édouard Herriot – Minister of State

- Louis Marin – Minister of State

- Pierre Étienne Flandin – Minister of State

Changes

- 17 June 1935 – Mario Roustan succeeds Marcombes (d. 13 June) as Minister of National Education. William Bertrand succeeds Roustan as Minister of Merchant Marine.

Laval's Ministry in the Vichy Government, 18 April 1942 – 20 August 1944

- Pierre Laval – President of the Council, Minister of Foreign Affairs, Minister of the Interior, and Minister of Information

- Eugène Bridoux – Minister of War

- Pierre Cathala – Minister of Finance and National Economy

- Jean Bichelonne – Minister of Industrial Production

- Hubert Lagardelle – Minister of Labour

- Joseph Barthélemy – Minister of Justice

- Gabriel Auphan – Minister of Marine

- Jean-François Jannekeyn – Minister of Air

- Abel Bonnard – Minister of National Education

- Jacques Le Roy Ladurie – Minister of Agriculture

- Max Bonnafous – Minister of Supply

- Jules Brévié – Minister of Colonies

- Raymond Grasset – Minister of Family and Health

- Robert Gibrat – Minister of Communication

- Lucien Romier – Minister of State

Changes

- 11 September 1942 – Max Bonnafous succeeds Le Roy Ladurie as Minister of Agriculture, remaining also Minister of Supply

- 18 November 1942 – Jean-Charles Abrial succeeds Auphan as Minister of Marine. Jean Bichelonne succeeds Gibrat as Minister of Communication, remaining also Minister of Industrial Production.

- 26 March 1943 – Maurice Gabolde succeeds Barthélemy as Minister of Justice. Henri Bléhaut succeeds Abrial as Minister of Marine and Brévié as Minister of Colonies.

- 21 November 1943 – Jean Bichelonne succeeds Lagardelle as Minister of Labour, remaining also Minister of Industrial Production and Communication.

- 31 December 1943 – Minister of State Lucien Romier resigns from the government.

- 6 January 1944 – Pierre Cathala succeeds Bonnafous as Minister of Agriculture and Supply, remaining also Minister of Finance and National Economy.

- 3 March 1944 – The office of Minister of Supply is abolished. Pierre Cathala remains Minister of Finance, National Economy, and Agriculture.

- 16 March 1944 – Marcel Déat succeeds Bichelonne as Minister of Labour and National Solidarity. Bichelonne remains Minister of Industrial Production and Communication.

References

- 1 2 "Laval's Body Taken To Family Mausoleum". Lubbock Morning Avalanche. Lubbock, Texas. November 16, 1945. p. 3. Retrieved August 2, 2016 – via Newspapers.com. (registration required (help)).

The bullet-pierced body of Pierre Laval was moved today to the mausoleum of the Chambrun family in Montparnasse cemetery from an unmarked grave in Thiais cemetery, where it had lain since the former premier was executed as a traitor a month ago.

- ↑ "Laval Execution", The Guardian, 16 October 2008

- ↑ Warner, Geoffrey, Pierre Laval and the Eclipse of France, New York: The Macmillan Company, 1968, p. 3

- ↑ Jaffré, Yves-Frédéric, Les: Derniers Propos de Pierre Laval, Paris: Andre Bonne, 1953, p. 55

- ↑ Privat, Maurice, Pierre Laval, Paris: Editions Les Documents secrets, 1931, pp. 67–8.

- ↑ Warner, p.4

- ↑ Torrés, Henry, Pierre Laval (Translated by Norbert Guterman), New York: Oxford University Press, 1941, pp. 17–20. Torrés was a close associate of Laval. "His entire physique, his filthy hands, his unkempt mustache, his disheveled hair, one lock of which was always falling down over his forehead, his powerful shoulders and careless dress, strikingly supported this profession. Even his white tie inspired confidence" pp. 18–19.

- ↑ "Herriot gémit: 'Si je pouvais, j'irais décharger moi-même les péniches.' La voix rauque du jeune député de la Seine s'élève, implacable: 'N'ajoutez pas le ridicule à l'incapacité!' Mallet, Pierre Laval des Années obscures, 18–19.

- ↑ Warner, Geoffrey, Pierre Laval and the Eclipse of France, New York: The Macmillan Company, 1968, pp. 19–20.

- ↑ Warner, p. 20

- ↑ Léon Blum, L'Œuvre de Léon Blum, Réparations et Désarmement, Les Problèmes de la Paix, La Montée des Fascismes, 1918–1934 (Paris: Albin Michel, 1972), 263.

- ↑ Tissier, Pierre, I worked with Laval, London: Harrap, 1942, p. 48.

- ↑ Bonnefous, Georges; Bonnefous, Edouard (1962). Histoire Politique de la Troisiéme République. V. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France. pp. 28–29.

- ↑

- ↑ Eichengreen, Barry and Harold James. International Monetary Cooperation Since Bretton Woods, P268

- ↑ Eichengreen and James, P270

- ↑ "Memorandum of Conference with Laval", Stimson, Diary, 23 October 1931.

- ↑ Original Time article

- ↑ André Larané, 4 janvier 1935: Laval rencontre Mussolini à Rome, Hérodote (French)

- ↑ For the only complete correspondence between Laval and Mussolini regarding this affair consult Benito Mussolini, Opera Omnia di Benito Mussolini, vol. XXVII, Dall'Inaugurazione Della Provincia Di Littoria Alla Proclamazione Dell'Impero (19 Dicembre 1934-9 Maggio 1936), eds. Edoardo and Duilio Susmel (Florence: La Fenice, 1951), 287.

- ↑ League of Nations Treaty Series, Vol. 167, pp.396-406.

- ↑ D. W. Brogan, The Development of Modern France (1870-1939) (London: Hamish Hamilton, 1945), pp.692-693.

- ↑ Correlli Barnett, The Collapse of British Power (London: Methuen, 1972), p.353.

- ↑ "Laval...was very reluctant to lose the fruits of his diplomacy, the separation of Italy and Germany, for such trivial reasons...He believed that to risk the loss of so important a stabilizing force in Europe as Italy, merely because of formal obligations to Abyssinia, was absurd". Brogan, p.693.

- ↑ Warner, p. 149

- ↑ Weygand, General Maxime, Mémoirs, Vol. III, Paris: Flammarion, 1950, pp. 168–88.

- ↑ Warner, pp.189–90.

- ↑ Baudouin, Paul, Neuf Mois au Gouvernement, Paris: La Table Ronde, 1948, p. 166.

- ↑ Lebrun, Albert, Témoignages, Paris: Plon, 1945. p. 85.

- ↑ Churchill, Winston S., "The Second World War, Vol. 2", p. 216.

- ↑ Darkness in Paris: The Allies and the eclipse of France 1940, Scribe Publications, Melbourne, Australia 2005, page 277

- ↑

- Chambrun, René de, Pierre Laval, Traitor or Patriot? (Translated by Elly Stein), New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1984, p. 50.

- ↑ Chambrun, pp 49–50

- ↑ Warner, p. 246.

- ↑ Warner, p. 255.

- ↑ Jaffré, Yves-Frédéric, Les Derniers Propos de Pierre Laval, Paris: Andre Bonne, 1953, p. 164.

- ↑ Warner, pp. 307–10, 364.

- ↑ Cole, Hubert, Laval, New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1963, pp. 210–11.

- ↑ Paldiel, Mordecai. Churches and the Holocaust: Unholy Teaching, Good Samaritans, and Reconciliation, p. 82

- ↑ Fishman, Sarah. The Battle for Children: World War II, Youth Crime, and Juvenile Justice in Twentieth-century France (Harvard University Press; 2002), p. 73

- ↑ Warner, p. 303

- ↑ Warner, p. 387

- ↑ Warner, pp. 396–7.

- ↑ Warner, pp. 404–407.

- ↑ Heinzen, Ralph (August 17, 1944). "Quislings Between Two Fires As France Falls. Laval May Head for Portugal--Fate of Petain Uncertain". The Republic. Columbus, Indiana. p. 9 – via Newspapers.com. (registration required (help)).

A law partner of his son-in-law, Count Rene de Chambrun, had gone to Portugal and leased an estate in Laval's name for three years. It is north of Lisbon near Cintra, on the sea and surrounded by high walls.

- ↑ Heinzen, Ralph (August 16, 1944). "Laval Ready to Flee When Nazis Leave France; Petain May Stick". The Coshocton Tribune. Coshocton, Ohio. p. 1. Retrieved August 2, 2016 – via Newspapers.com. (registration required (help)).

A law partner of his son-in-law, Count Rene de Chambrun, had gone to Portugal and leased an estate in Laval's name for three years. It is north of Lisbon near Cintra, on the sea and surrounded by high walls.

- ↑ Paxton, Robert O., Vichy France, Old Guard and New Order 1940–1944, New York: Columbia University Press, 1972 (1982) p.425

- ↑ Warner, p.408

- ↑ Laval, Pierre, The Diary of Pierre Laval (With a Preface by his daughter, Josée Laval), New York: Scribner's Sons, 1948.

- ↑ Naud, Albert. Pourquoi je n'ai pas défendu Pierre Laval, Paris: Fayard, 1948

- ↑ Baraduc, Jaques, Dans la Cellule de Pierre Laval, Paris: Editions Self, 1948, p. 31.

- ↑ Cole, Hubert, Laval, New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1963,pp. 280–1.

- ↑ Naud, p.249; Baraduc, p.143; Jaffré, p.263.

- ↑ Laval Parle, Notes et Mémoires Rediges par Pierre Laval dans sa cellule, avec une préface de sa fille et de Nombreux Documents Inédits, Constant Bourquin (Editor), pp. 13–15

- ↑ Le Procès Laval: Compte-rendu sténographique, Maurice Garçon (Editor), Paris: Albin Michel, 1946, pp. 91.

- ↑ Le Proces Laval, pp. 207–209.

- ↑ Naud, pp. 249–57; Baraduc, pp. 143–6; Jaffré, pp. 263–7.

- ↑ Warner. p. 415-6. For detailed accounts of Laval's execution, see Naud, pp. 276–84; Baraduc, pp. 188–200; Jaffré, pp. 308–18.

- ↑ Chambrun, René de, Mission and Betrayal 1949-1945, London: André Deutch, 1993, p. 134.

- ↑ Evening Standard, 16 October 1945 (cover page).

- ↑ "Laval's Body Moved To Chambrun Crypt". Harrisburgh Telegraph. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. November 15, 1945. p. 10. Retrieved August 2, 2016 – via Newspapers.com. (registration required (help)).

- 1 2 Pegler, Westbrook (July 23, 1954). "Of 'Human Events'". The Monroe News-Star. Monroe, Louisiana. p. 4. Retrieved August 2, 2016 – via Newspapers.com. (registration required (help)).

- 1 2 Pegler, Westbrook (June 23, 1954). "Pegler Tells France's Case Against Britain, U. S.". El Paso Herald-Post. El Paso, Texas. p. 16. Retrieved August 2, 2016 – via Newspapers.com. (registration required (help)).

- 1 2 Pegler, Westbrook (July 23, 1954). "As Pegler Sees It". The Kingston Daily Freeman. Kingston, New York. p. 4. Retrieved August 2, 2016 – via Newspapers.com. (registration required (help)).

- ↑ Curtis, Michael, Verdict on Vichy, New York: Arcade Publishing, 2002, p.346-7

Further reading

Critical of Laval

- Tissier, Pierre, I worked with Laval, London: George Harrap & Co, 1942

- Torrés, Henry, Pierre Laval (Translated by Norbert Guterman), New York: Oxford University Press, 1941

- Bois, Elie J., Truth on the Tragedy of France, (London, 1941)

- Pétain-Laval The Conspiracy, With a Foreword by Viscount Cecil, London: Constable, 1942

- Marrus, Michael & Paxton, Robert O. Vichy France and the Jews, New York: Basic Books New York 1981,

Post-war defences of Laval

- Julien Clermont (pseudonym for Georges Hilaire), L'Homme qu'il fallait tuer (Paris, 1949)

- Jacques Guerard, Criminel de Paix (Paris, 1953)

- Michel Letan, Pierre Laval de l'armistice au poteau (Paris, 1947)

- Alfred Mallet, Pierre Laval (Paris, 1955)

- Maurice Privat, Pierre Laval, cet inconnu (Paris, 1948)

- René de Chambrun, Pierre Laval, Traitor or Patriot?, (New York) 1984; and Mission and Betrayal, (London, 1993).

- Whitcomb, Philip W., France During The German Occupation 1940–1944, Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 1957, In three vol.

Books by Laval's lawyers

- Baraduc, Jaques, Dans la Cellule de Pierre Laval, Paris: Editions Self, 1948

- Jaffré, Yves-Frédéric, Les Derniers Propos de Pierre Laval, Paris: Andre Bonne, 1953

- Naud, Albert, Pourquoi je n'ai pas défendu Pierre Laval, Paris: Fayard 1948

Full biographies

- Cointet, Jean-Paul, Pierre Laval, Paris: Fayard, 1993

- Cole, Hubert, Laval, New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1963

- Kupferman, Fred, Laval 1883–1945, Paris: Flammarion, 1988

- Pourcher, Yves, Pierre Laval vu par sa fille, Paris: Le Grande Livre du Mois, 2002

- Warner, Geoffrey, Pierre Laval and the eclipse of France, New York: The Macmillan Company, 1968

Other biographical material

- "Man of the Year", Time (profile), 4 January 1932.

- "France: That Flabby Hand, That Evil Lip", Time (cover story), 27 April 1942.

- "Devil's Advocate". Time magazine. 15 October 1945. Retrieved 10 August 2008. on the Laval treason trial, 15 Oct 1945.

- "What Is Honor?". Time. 13 August 1945. Retrieved 10 August 2008. on Laval's testimony in Petain's trial, 13 Aug 1945.

- Abrahamsen, David (1945), Men, Mind, and Power, New York: Columbia University Press.

- Bonnefous, Georges; Bonnefous, Edouard (1962), Histoire Politique de la Troisième République [Political History of the Third Republic] (in French), V, Paris: Presses Universitaires de France.

- Brody, J Kenneth (2000), The Avoidable War: Pierre Laval & Politics of Reality 1935–1936, 2, New Brunswick: Transaction.

- Bechtel, Guy (1963), Laval, vingt ans après [Laval, twenty years later] (in French), Paris: Robert Laffont.

- de Chambrun, René (1983), Laval, Devant L'History [Laval before History] (in French), Paris: France‐empire.

- ——— (1993), Mission and Betrayal 1939–1945, London: André Deutch.

- Clermont, Julien (1949), L'homme qu'il Fallait Tuer – Pierre Laval [The Man that had to die – Pierre Laval] (in French), Paris: Les Actes des Apôtres.

- Curtis, Michael, Verdict on Vichy, New York: Arcade, 2002

- De Gaulle, Charles (1959), Mémoires de Guerre [War memories] (in French), III, Le Salut 1944–46, Paris: Plon.

- Farmer, Paul, Vichy – Political Dilemma, London: Oxford University Press, 1955

- Gounelle, Claude (1969), Le Dossier Laval [The Laval dossier] (in French), Paris: Plon.

- Gun, Nerin E (1979), Les secrets des archives américaines, Pétain, Laval, De Gaulle [The American files secrets: Pétain, Laval, de Gaulle] (in French), Paris: Albin Michel.

- Jacquemin, Gason (1973), La vie publique de Pierre Laval [The public life of Pierre Laval] (in French), Paris: Plon.

- Laval, Pierre (1947), Bourquin, Constant, ed., Laval Parle, Notes et Mémoires Rédigées par Pierre Laval dans sa cellule, avec une préface de sa fille et de Nombreux Documents Inédits [Laval speaks: notes & memories written in his cell, with a preface by his daughter and many unseen documents] (in French), Geneva: Cheval Ailé.

- ——— (1948), The Unpublished Diary, London: Falcon.

- ——— (1948), The Diary (With a Preface by his daughter, Josée Laval), New York: Scribner's Sons.

- Garçon, Maurice, ed. (1946), Le Procés Laval: Compte-rendu sténographique [The Laval process: stenographic acts] (in French), Paris: Albin Michel.

- Letan, Michel (1947), Pierre Laval – de l'armistice au Poteau [Pierre Laval – from the armistice to Poteau] (in French), Paris: La Couronne.

- Mallet (1955), Pierre Laval, I & II, Paris: Amiot Dumont.

- Pannetier, Odette (1936), Pierre Laval, Paris: Denoél & Steele.

- Paxton, Robert O (1982) [1972], Vichy France, Old Guard and New Order 1940–1944, New York: Columbia University Press.

- Pertinax (1944), The Gravediggers of France, New York: Doubleday, Doran & Co.

- Privat, Maurice (1931), Pierre Laval, Paris: Les Documents secrets.

- ——— (1948), Pierre Laval, cet inconnu [Pierre Laval, this unknown] (in French), Paris: Fourner-Valdés.

- Saurel, Louis (1965), La Fin de Pierre Laval [The end of Pierre Laval] (in French), Paris: Rouff.

- Thompson, David (1951), Two Frenchmen: Pierre Laval and Charles de Gaulle, London: Cresset.

- Volcker, Sebastian (1998), Laval 1931, A Diplomatic Study (thesis), University of Richmond.

- Weygand, Général Maxime (1950), Mémoires [Memoirs] (in French), III, Paris: Flammarion.

- The London Evening Standard, p. 1, 15–17 October 1945 Missing or empty

|title=(help). - "The Donald Prell Pierre Laval Collection", The Special Collections Library (collection containing all of the books and other reference material listed in the Notes and References as well as many other items concerning Pierre Laval), The University of California Riverside.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pierre Laval. |

- "Nazi diplomacy: Vichy, 1940", World War (essay), Hist clo.

- View auction of Laval's possessions in 1944, ITN source.

- The short film A German is tried for murder [&c (1945)] is available for free download at the Internet Archive

- "Pierre Laval: Devil's Advocate", Learn Law, Law's Hall of Shame, Duhaime.