The Pilgrim's Progress

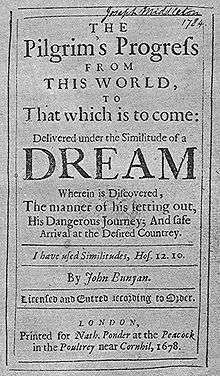

First edition cover | |

| Author | John Bunyan |

|---|---|

| Country | England |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Religious allegory |

Publication date | 1678 |

The Pilgrim's Progress from This World to That Which Is to Come; Delivered under the Similitude of a Dream is a 1678 Christian allegory written by John Bunyan. It is regarded as one of the most significant works of religious English literature,[1][2][3][4] has been translated into more than 200 languages, and has never been out of print.[5][6]

Bunyan began his work while in the Bedfordshire county prison for violations of the Conventicle Act, which prohibited the holding of religious services outside the auspices of the established Church of England. Early Bunyan scholars such as John Brown believed The Pilgrim's Progress was begun in Bunyan's second, shorter imprisonment for six months in 1675,[7] but more recent scholars such as Roger Sharrock believe that it was begun during Bunyan's initial, more lengthy imprisonment from 1660 to 1672 right after he had written his spiritual autobiography, Grace Abounding to the Chief of Sinners.[8]

The English text comprises 108,260 words and is divided into two parts, each reading as a continuous narrative with no chapter divisions. The first part was completed in 1677 and entered into the Stationers' Register on 22 December 1677. It was licensed and entered in the "Term Catalogue" on 18 February 1678, which is looked upon as the date of first publication.[9] After the first edition of the first part in 1678, an expanded edition, with additions written after Bunyan was freed, appeared in 1679. The Second Part appeared in 1684. There were eleven editions of the first part in John Bunyan's lifetime, published in successive years from 1678 to 1685 and in 1688, and there were two editions of the second part, published in 1684 and 1686.

Plot summary

First Part

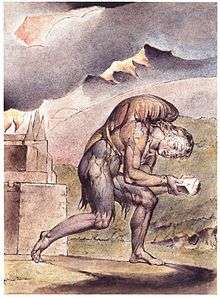

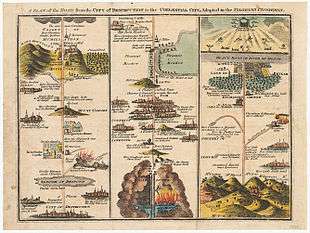

The entire book is presented as a dream sequence narrated by an omniscient narrator. The allegory's protagonist, Christian, is an everyman character, and the plot centres on his journey from his hometown, the "City of Destruction" ("this world"), to the "Celestial City" ("that which is to come": Heaven) atop Mount Zion. Christian is weighed down by a great burden—the knowledge of his sin—which he believed came from his reading "the book in his hand" (the Bible). This burden, which would cause him to sink into Hell, is so unbearable that Christian must seek deliverance. He meets Evangelist as he is walking out in the fields, who directs him to the "Wicket Gate" for deliverance. Since Christian cannot see the "Wicket Gate" in the distance, Evangelist directs him to go to a "shining light," which Christian thinks he sees.[10] Christian leaves his home, his wife, and children to save himself: he cannot persuade them to accompany him. Obstinate and Pliable go after Christian to bring him back, but Christian refuses. Obstinate returns disgusted, but Pliable is persuaded to go with Christian, hoping to take advantage of the Paradise that Christian claims lies at the end of his journey. Pliable's journey with Christian is cut short when the two of them fall into the Slough of Despond, a boggy mire-like swamp where pilgrims' doubts, fears, temptations, lusts, shames, guilts, and sins of their present condition of being a sinner are used to sink them into the mud of the swamp. It is there in that bog where Pliable abandons Christian after getting himself out. After struggling to the other side of the slough, Christian is pulled out by Help, who has heard his cries and tells him the swamp is made out of the decadence, scum, and filth of sin, but the ground is good at the narrow Wicket Gate.

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

On his way to the Wicket Gate, Christian is diverted by the secular ethics of Mr. Worldly Wiseman into seeking deliverance from his burden through the Law, supposedly with the help of a Mr. Legality and his son Civility in the village of Morality, rather than through Christ, allegorically by way of the Wicket Gate. Evangelist meets the wayward Christian as he stops before Mount Sinai on the way to Mr. Legality's home. It hangs over the road and threatens to crush any who would pass it; also the mountain flashed with fire. Evangelist shows Christian that he had sinned by turning out of his way and tells him that Mr. Legality and his son Civility are descendants of slaves and Mr. Worldly Wiseman is a false guide, but he assures him that he will be welcomed at the Wicket Gate if he should turn around and go there, which Christian does.

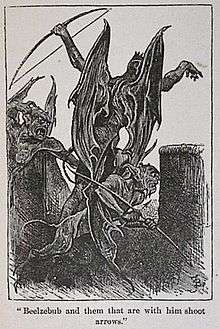

At the Wicket Gate begins the "straight and narrow" King's Highway, and Christian is directed onto it by the gatekeeper Goodwill who saves him from Beelzebub's archers at Beelzebub's castle near the Wicket Gate and shows him the heavenly way he must go. In the Second Part, Goodwill is shown to be Jesus himself.[11] To Christian's query about relief from his burden, Goodwill directs him forward to "the place of deliverance."[8][12]

Christian makes his way from there to the House of the Interpreter, where he is shown pictures and tableaux that portray or dramatize aspects of the Christian faith and life. Roger Sharrock denotes them "emblems".[8][13]

From the House of the Interpreter, Christian finally reaches the "place of deliverance" (allegorically, the cross of Calvary and the open sepulchre of Christ), where the "straps" that bound Christian's burden to him break, and it rolls away into the open sepulchre. This event happens relatively early in the narrative: the immediate need of Christian at the beginning of the story being quickly remedied. After Christian is relieved of his burden, he is greeted by three angels, who give him the greeting of peace, new garments, and a scroll as a passport into the Celestial City. Encouraged by all this, Christian happily continues his journey until he comes upon three men named Simple, Sloth, and Presumption. Christian tries to help them, but they disregard his advice. Before coming to the Hill of Difficulty, Christian meets two well-dressed men named Formality and Hypocrisy who prove to be false Christians that perish in the two, dangerous bypasses near the hill named Danger and Destruction. Christian falls asleep at the arbor above the hill and loses his scroll, forcing him to go back and get it. Near the top of the Hill of Difficulty, he meets two weak pilgrims named Mistrust and Timorous who tell him of the great lions of the Palace Beautiful. Christian frightfully avoids the lions through Watchful the porter who tells them that they are chained and put there to test the faith of pilgrims.

Atop the Hill of Difficulty, Christian makes his first stop for the night at the House of the Palace Beautiful, which is a place built by God for the refresh of pilgrims and godly travelers. Christian spends three days here, and leaves clothed with the Armor of God (Eph. 6:11–18),[14] which stands him in good stead in his battle against the demonic dragon-like Apollyon, (the lord and god of the City of Destruction) in the Valley of Humiliation. This battle lasts "over half a day" until Christian manages to wound and stab Apollyon with his two-edged sword (a reference to the Bible, Heb. 4:12).[15] "And with that Apollyon spread his dragon wings and sped away."

As night falls Christian enters the fearful Valley of the Shadow of Death. When he is in the middle of the Valley amidst the gloom, terror and demons, he hears the words of the Twenty-third Psalm, spoken possibly by his friend Faithful:

Yea, though I walk through the Valley of the Shadow of Death, I will fear no evil: for thou art with me; thy rod and thy staff they comfort me. (Psalm 23:4.)

As he leaves this valley the sun rises on a new day.

Just outside the Valley of the Shadow of Death he meets Faithful, also a former resident of the City of Destruction, who accompanies him to Vanity Fair, a place built by Beelzebub where every thing to a human's tastes, delights, and lusts are sold daily, where both are arrested and detained because of their disdain for the wares and business of the Fair. Faithful is put on trial, and executed by burning at the stake as a martyr. A celestial chariot then takes Faithful to the Celestial City, martyrdom being a shortcut there. Hopeful, a resident of Vanity Fair, takes Faithful's place to be Christian's companion for the rest of the way.

Christian and Hopeful then come to a mining hill called Lucre. Its owner named Demas offers them all the silver of the mine but Christian sees through Demas's trickery and they avoid the mine. Afterwards, a false pilgrim named By-Ends and his friends, who followed Christian and Hopeful only to take advantage of them, perish at the Hill Lucre, never to be seen or heard again. Along a rough, stony stretch of road, Christian and Hopeful leave the highway to travel on the easier By-Path Meadow, where a rainstorm forces them to spend the night. In the morning they are captured by Giant Despair, who is known for his savage cruelty, and his wife Diffidence; the pilgrims are taken to the Giant's Doubting Castle, where they are imprisoned, beaten and starved. The Giant and the Giantess want them to commit suicide, but they endure the ordeal until Christian realizes that a key he has, called Promise, will open all the doors and gates of Doubting Castle. Using the key and the Giant's weakness to sunlight, they escape.

The Delectable Mountains form the next stage of Christian and Hopeful's journey, where the shepherds show them some of the wonders of the place also known as "Immanuel's Land". The pilgrims are shown sights that strengthen their faith and warn them against sinning, like the Hill Error or the Mountain Caution. On Mount Clear they are able to see the Celestial City through the shepherd's "perspective glass", which serves as a telescope. (This device is given to Mercy in the Second Part at her request.) The shepherds tell the pilgrims to beware of the Flatterer and to avoid the Enchanted Ground. Soon they come to a crossroad and a man dressed in white comes to help them. Thinking he is a "shining one" (angel), the pilgrims follow the man, but soon get stuck in a net and realize their so-called angelic guide was the Flatterer. A true shining one comes and frees them from the net. The Angel punishes them for following the Flatterer and then puts them back on the right path. The pilgrims meet Atheist, who tells them Heaven and God don't exist, but Christian and Hopeful remember the shepherds and pay no attention to the man. Christian and Hopeful come to a place where a man named Little-Faith is chained by the ropes of seven demons who take him to a shortcut to the Lake of Fire (Hell).

On the way, Christian and Hopeful meet a lad named Ignorance, who believes that he will be allowed into the Celestial City through his own good deeds rather than as a gift of God's grace. Christian and Hopeful meet up with him twice and try to persuade him to journey to the Celestial City in the right way. Ignorance persists in his own way that he thinks will lead him into Heaven. After getting over the River of Death on the ferry boat of Vain Hope without overcoming the hazards of wading across it, Ignorance appears before the gates of Celestial City without a passport, which he would have acquired had he gone into the King's Highway through the Wicket Gate. The Lord of the Celestial City orders the shining ones (angels) to take Ignorance to one of the byways of Hell and throw him in.

Christian and Hopeful make it through the dangerous Enchanted Ground (a place where the air makes them sleepy and if they fall asleep, they never wake up) into the Land of Beulah, where they ready themselves to cross the dreaded River of Death on foot to Mount Zion and the Celestial City. Christian has a rough time of it because of his past sins wearing him down, but Hopeful helps him over; and they are welcomed into the Celestial City.

Second Part

The Second Part of The Pilgrim's Progress presents the pilgrimage of Christian's wife, Christiana; their sons; and the maiden, Mercy. They visit the same stopping places that Christian visited, with the addition of Gaius' Inn between the Valley of the Shadow of Death and Vanity Fair, but they take a longer time in order to accommodate marriage and childbirth for the four sons and their wives. The hero of the story is Great-Heart, a servant of the Interpreter, who is the pilgrims' guide to the Celestial City. He kills four giants called Giant Grim, Giant Maul, Giant Slay-Good, and Giant Despair and participates in the slaying of a monster called Legion that terrorizes the city of Vanity Fair.

The passage of years in this second pilgrimage better allegorizes the journey of the Christian life. By using heroines, Bunyan, in the Second Part, illustrates the idea that women as well as men can be brave pilgrims.

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: John Bunyan |

Alexander M. Witherspoon, professor of English at Yale University, writes in a prefatory essay:

Part II, which appeared in 1684, is much more than a mere sequel to or repetition of the earlier volume. It clarifies and reinforces and justifies the story of Part I. The beam of Bunyan's spotlight is broadened to include Christian's family and other men, women, and children; the incidents and accidents of everyday life are more numerous, the joys of the pilgrimage tend to outweigh the hardships; and to the faith and hope of Part I is added in abundant measure that greatest of virtues, charity. The two parts of The Pilgrim's Progress in reality constitute a whole, and the whole is, without doubt, the most influential religious book ever written in the English language.[16]

This is exemplified by the frailness of the pilgrims of the Second Part — women, children, and physically and mentally challenged individuals — in contrast to the stronger pilgrims of the First Part. When Christiana's party leaves Gaius's Inn and Mr. Feeble-Mind lingers in order to be left behind, he is encouraged to accompany the party by Greatheart:

But brother ... I have it in commission, to comfort the feeble-minded, and to support the weak. You must needs go along with us; we will wait for you, we will lend you our help, we will deny ourselves of some things, both opinionative and practical, for your sake; we will not enter into doubtful disputations before you, we will be made all things to you, rather than you shall be left behind.[8]

The pilgrims learn of Madame Bubble who created the Enchanted Ground and Forgetful Green, a place in the Valley of Humiliation where the flowers make other pilgrims forget about God's love. Christiana, Matthew, Joseph, Samuel, James, Mercy, Great Heart, Mr. Feeble Mind, and Mr. Ready-To-Halt come to Bypath-Meadow and, after much fight and difficulty, slay the cruel Giant Despair and the wicked Giantess Diffidence, and demolish Doubting Castle for Christian and Hopeful who were oppressed there. They free a pale man named Mr. Despondency and his daughter named Much-Afraid from the castle's dungeons.

When the pilgrims end up in the Land of Beulah, they cross over the River of Death by appointment. As a matter of importance to Christians of Bunyan's persuasion reflected in the narrative of The Pilgrim's Progress, the last words of the pilgrims as they cross over the River of Death are recorded. The four sons of Christian and their families do not cross, but remain for the support of the church in that place.

Characters

First Part

- Christian, who was born named Graceless, the protagonist in the First Part, whose journey to the Celestial City is the plot of the story.

- Evangelist, the religious man who puts Christian on the path to the Celestial City. He also shows Christian a book, which readers assume to be the Bible.

- Obstinate, one of the two residents of the City of Destruction, who run after Christian when he first sets out, in order to bring him back. Like his name, he is stubborn and is disgusted with Christian and with Pliable for making a journey that he thinks is nonsense.

- Pliable, the other of the two, who goes with Christian until both of them fall into the Slough of Despond, (a boggy mire composed of the decadence and filthiness of sin and a swamp that makes the fears and doubts of a present and past sinner real). Pliable escapes from the slough and returns home. Like his name, he is insecure and goes along with some things for a little while but quickly gives up on them.

- Help, Christian's rescuer from the Slough of Despond.

- Mr. Worldly Wiseman, a resident of a place called Carnal Policy, who persuades Christian to go out of his way to be helped by a friend named Mr. Legality and then move to the City of Morality, (which focuses salvation on the Law and good deeds instead of faith and love in Jesus Christ). His real advice is from the world and not from God, meaning his advice is flawed and consisted of three objectives: getting Christian off the right path, making the cross of Jesus Christ offensive to him, and binding him to the Law so he would die with his sins. Worldly Wiseman has brought down many innocent pilgrims and there will be many more to come.

- Goodwill, the keeper of the Wicket Gate through which one enters the "straight and narrow way" (also referred to as "the King's Highway") to the Celestial City. In the Second Part we find that this character is none other than Jesus Christ Himself.

- Beelzebub, literally "Lord of the Flies," is one of Satan's companion archdemons, who has erected a fort near the Wicket Gate from which he and his soldiers can shoot arrows of fire at those about to enter the Wicket Gate so they will never enter it. He is also the Lord, God, King, Master, and Prince of Vanity Fair. Christian calls him "captain" of the Foul Fiend Apollyon, who he later met in the Valley of Humiliation.[8]

- The Interpreter, the one who has his House along the way as a rest stop for travellers to check in to see pictures and dioramas to teach them the right way to live the Christian life. He has been identified in the Second Part as the Holy Spirit.

- Shining Ones, the messengers and servants of "the Lord of the Hill," God. They are obviously the holy angels.

- Formalist, one of two travelers and false pilgrims on the King's Highway, who do not come in by the Wicket Gate, but climb over the wall that encloses it, at least from the hill and sepulchre up to the Hill Difficulty. He and his companion Hypocrisy come from the land of Vainglory. He takes one of the two bypaths that avoid the Hill Difficulty, but is lost.

- Hypocrisy, the companion of Formalist and the other false pilgrim. He takes the other of the two bypaths and is also lost.

- Timorous, one of two men who try to persuade Christian to go back for fear of the chained lions near the House Beautiful. He is a relative of Mrs. Timorous of the Second Part. His companion is Mistrust.

- Watchful, the porter of the House Beautiful. He also appears in the Second Part and receives "a gold angel" coin from Christiana for his kindness and service to her and her companions. "Watchful" is also the name of one of the Delectable Mountains' shepherds.

- Discretion, one of the beautiful maids of the house, who decides to allow Christian to stay there.

- Prudence, another of the House Beautiful maidens. She appears in the Second Part.

- Piety, another of the House Beautiful maidens. She appears in the Second Part.

- Charity, another of the House Beautiful maidens. She appears in the Second Part.

- Apollyon, literally "Destroyer;" the King, Lord, God, Master, Prince, Owner, Landlord, Ruler, Governor, and Leader of the City of Destruction where Christian was born. He is one of Satan's companion archdemons, who tries to force Christian to return to his domain and service. His battle with Christian takes place in the Valley of Humiliation, just below the House Beautiful. He appears as a huge demonic creature with fish's scales, mouth of a lion, feet of a bear, second mouth on his belly, and dragon's wings. He takes fiery darts from his body to throw at his opponents. Apollyon is finally defeated when Christian uses the Sword of the Spirit to wound him two times.

- "Pope" and "Pagan," giants living in a cave at the end of the fearsome Valley of the Shadow of Death. They are allegories of Roman Catholicism and paganism as persecutors of Protestant Christians. "Pagan" is dead, indicating the end of pagan persecution with Antiquity, and "Pope" is alive but decrepit, indicating the then diminished power and influence of the Roman Catholic pope. In the Second Part, Pagan is resurrected by a demon from the bottomless pit of the Valley of the Shadow of Death, representing the new age of pagan persecution, and Pope is revived of his deadly wounds and is no longer stiff and unable to move, representing the beginning of the Christian's troubles with Roman Catholic popes.

- Faithful, Christian's friend from the City of Destruction, who is also going on pilgrimage. Christian meets Faithful just after getting through the Valley of The Shadow of Death. He dies later in Vanity Fair for his strong faith and first reaches the Celestial City.

- Wanton, a temptress who tries to get Faithful to leave his journey to the Celestial City. She may be the popular resident of the City of Destruction, Madam Wanton, who hosted a house party for friends of Mrs. Timorous.

- Adam the First, "the old man" (representing carnality and deceit) who tries to persuade Faithful to leave his journey and come live with his 3 daughters: the Lust of the Flesh, the Lust of the Eyes, and the Pride of Life.

- Moses, the severe, violent avenger (representing the Law, which knows no mercy) who tries to kill Faithful for his momentary weakness in wanting to go with Adam the First out of the way. Moses is sent away by Jesus Christ.

- Talkative, a pilgrim that Faithful and Christian meet after going through the Valley of the Shadow of Death. He is known to Christian as a fellow resident of the City of Destruction, living on Prating Row. He is the son of Say-Well and Mrs. Talk-About-The-Right Things. He is said to be better looking from a distance than close up. His enthusiasm for talking about his faith to Faithful deceives him into thinking that he is a sincere man. Christian lets Faithful know about his unsavory past, and in a conversation that Faithful strikes up with him he is exposed as shallow and hypocritical in his Christianity.

- Lord Hate-Good, the evil judge who tries Faithful in Vanity Fair. Lord Hate-Good is the opposite of a judge, he hates right and loves wrong because he does wrong himself. His jury are twelve vicious rogue men.

- Envy, the first witness against Faithful who falsely accuses that Faithful shows no respect for their prince, Lord Beelzebub.

- Superstition, the second witness against Faithful who falsely accuses Faithful of saying that their religion is vain.

- Pick-Thank, the third witness against Faithful who falsely accuses Faithful of going against their prince, their people, their laws, their "honorable" friends, and the judge himself.

- Hopeful, the resident of Vanity Fair, who takes Faithful's place as Christian's fellow traveler. The character Hopeful poses an inconsistency in that there is a necessity imposed on the pilgrims that they enter the "King's Highway" by the Wicket Gate. Hopeful did not; however, of him we read: "... one died to bear testimony to the truth, and another rises out of his ashes to be a companion with Christian in his pilgrimage." Hopeful assumes Faithful's place by God's design. Theologically and allegorically it would follow in that "faith" is trust in God as far as things present are concerned, and "hope," biblically the same as "faith," is trust in God as far as things of the future are concerned. Hopeful would follow Faithful. The other factor is Vanity Fair's location right on the straight and narrow way. Ignorance, in contrast to Hopeful, was unconcerned about the end times of God, unconcerned with true faith in Jesus Christ, and gave false hope about the future. Ignorance was told by Christian and Hopeful that he should have entered the highway through the Wicket Gate.

- Mr. By-Ends, a false pilgrim met by Christian and Hopeful after they leave Vanity Fair. He makes it his aim to avoid any hardship or persecution that Christians may have to undergo. He supposedly perishes in the Hill Lucre (a dangerous silver mine) with three of his friends, Hold-the-World, Money-Love, and Save-All, at the behest of Demas, who invites passersby to come and see the mine. A "by-end" is a pursuit that is achieved indirectly. For By-Ends and his companions, it is the by-end of financial gain through religion.

- Demas, a deceiver, who beckons to pilgrims at the Hill Lucre to come and join in the supposed silver mining going on in it. He is first mentioned in the Book of 2 Timothy by the disciple Paul when he said, "Demas has deserted us because he loved the world". Demas tries two ways to trick Christian and Hopeful: first he claims that the mine is safe and they'll be rich, and then he claims that he is a pilgrim and will join them on their journey. Christian, filled with the Holy Spirit, is able to rebuke Demas and expose his lies.

- Giant Despair, the savage owner of Doubting Castle, where pilgrims are imprisoned and murdered. He is slain by Great-Heart in the Second Part.

- Giantess Diffidence, Despair's wife known to be cruel, savage, violent, and evil like her husband. She is slain by Old Honest in the Second Part.

- Knowledge, one of the shepherds of the Delectable Mountains.

- Experience, another of the Delectable Mountains shepherds.

- Watchful, another of the Delectable Mountains shepherds.

- Sincere, another of the Delectable Mountains shepherds.

- Ignorance, "the brisk young lad", (representing foolishness and conceit) who joins the "King's Highway" by way of the "crooked lane" that comes from his native country, called "Conceit." He follows Christian and Hopeful and on two occasions talks with them. He believes that he will be received into the Celestial City because of his doing good works in accordance with God's will. For him, Jesus Christ is only an example, not a Savior. Christian and Hopeful try to set him right, but they fail. He gets a ferryman, Vain-Hope, to ferry him across the River of Death rather than cross it on foot as one is supposed to do. When he gets to the gates of the Celestial City, he is asked for a "certificate" needed for entry, which he does not have. The King upon hearing this, then, orders that he be bound and cast into Hell.

- The Flatterer, a deceiver dressed as an angel who leads Christian and Hopeful out of their way, when they fail to look at the road map given them by the Shepherds of the Delectable Mountains.

- Atheist, a mocker of Christian and Hopeful, who goes the opposite way on the "King's Highway" because he boasts that he knows that God and the Celestial City do not exist.

Second Part

- Mr. Sagacity, a guest narrator who meets Bunyan himself in his new dream and recounts the events of the Second Part up to the arrival at the Wicket Gate.

- Christiana, wife of Christian, who leads her four sons and neighbour Mercy on pilgrimage.

- Matthew, Christian and Christiana's eldest son, who marries Mercy.

- Samuel, second son, who marries Grace, Mr. Mnason's daughter.

- Joseph, third son, who marries Martha, Mr. Mnason's daughter.

- James, fourth and youngest son, who marries Phoebe, Gaius's daughter.

- Mercy, Christiana's neighbour, who goes with her on pilgrimage and marries Matthew.

- Mrs. Timorous, relative of the Timorous of the First Part, who comes with Mercy to see Christiana before she sets out on pilgrimage.

- Mrs. Bat's-Eyes, a resident of The City of Destruction and friend of Mrs. Timorous. Since she has a bat's eyes, she would be blind or nearly blind, so her characterization of Christiana as blind in her desire to go on pilgrimage is hypocritical.

- Mrs. Inconsiderate, a resident of The City of Destruction and friend of Mrs. Timorous. She characterizes Christiana's departure "a good riddance" as an inconsiderate person would.

- Mrs. Light-Mind, a resident of The City of Destruction and friend of Mrs. Timorous. She changes the subject from Christiana to gossip about being at a bawdy party at Madam Wanton's home.

- Mrs. Know-Nothing, a resident of The City of Destruction and friend of Mrs. Timorous. She wonders if Christiana will actually go on pilgrimage.

- Ill-favoured Ones, two evil characters Christiana sees in her dream, whom she and Mercy actually encounter when they leave the Wicket Gate. The two Ill Ones are driven off by Great-Heart himself.

- Innocent, a young serving maid of the Interpreter, who answers the door of the house when Christiana and her companions arrive; and who conducts them to the garden bath, which signifies Christian baptism.

- Mr. Great-Heart, the guide and body-guard sent by the Interpreter with Christiana and her companions from his house to their journey's end. He proves to be one of the main protagonists in the Second Part.

- Giant Grim, a Giant who "backs the [chained] lions" near the House Beautiful, slain by Great-Heart. He is also known as "Bloody-Man" because he has killed many pilgrims or sent them on mazes of detours, where they were lost forever.

- Humble-Mind, one of the maidens of the House Beautiful, who makes her appearance in the Second Part. She questions Matthew, James, Samuel, and Joseph about their godly faith and their hearts to the Lord God.

- Mr. Brisk, a suitor of Mercy's, who gives up courting her when he finds out that she makes clothing only to give away to the poor. He is shown to be a foppish, worldy-minded person who is double minded about his beliefs.

- Mr. Skill, the godly physician called to the House Beautiful to cure Matthew of his illness, which is caused by eating the forbidden apples and fruits of Beelzebub which his mother told him not to but he did it any way.

- Giant Maul, a Giant whom Great-Heart kills as the pilgrims leave the Valley of the Shadow of Death. He holds a grudge against Great-Heart or doing his duty of saving pilgrim's from damnation and bringing them from darkness to light, from evil to good, and from Satan, the Devil to Jesus Christ, the Savior.

- Old Honest, a pilgrim from the frozen town of Stupidity who joins them, a welcome companion to Great-Heart. Old Honest tells the stories of Mr. Fearing and a prideful villain named Mr. Self-Will.

- Mr. Fearing, a fearful pilgrim from the City of Destruction whom Great-Heart had "conducted" to the Celestial City in an earlier pilgrimage. Noted for his timidness of Godly Fears such as temptations and doubts. He is Mr. Feeble-Mind's uncle.

- Gaius, an innkeeper with whom the pilgrims stay for some years after they leave the Valley of the Shadow of Death. He gives his daughter Phoebe to James in marriage. The lodging fee for his inn is paid by the Good Samaritan. Gaius tells them of the wicked Giant Slay-Good.

- Giant Slay-Good, a Giant who enlists the help of evil-doers on the King's Highway to abduct, murder, and consume pilgrims before they get to Vanity Fair. He is killed by Great-Heart.

- Mr. Feeble-Mind, rescued from Slay-Good by Mr. Great-Heart, who joins Christiana's company of pilgrims. He is the nephew of Mr. Fearing.

- Phoebe, Gaius's daughter, who marries James.

- Mr. Ready-to-Halt, a pilgrim who meets Christiana's train of pilgrims at Gaius's door, and becomes the companion of Mr. Feeble-mind, to whom he gives one of his crutches.

- Mr. Mnason, a resident of the town of Vanity, who puts up the pilgrims for a time, and gives his daughters Grace and Martha in marriage to Samuel and Joseph respectively.

- Grace, Mnason's daughter, who marries Samuel.

- Martha, Mnason's daughter, who marries Joseph.

- Mr. Despondency, a rescued prisoner from Doubting Castle owned by the miserable Giant Despair.

- Much-Afraid, his daughter.

- Mr. Valiant, a pilgrim they find all bloody, with his sword in his hand, after leaving the Delectable Mountains. He fought and defeated three robbers called Faint-Heart, Mistrust, and Guilt.

- Mr. Stand-Fast For-Truth, a pilgrim found while praying for deliverance from Madame Bubble.

- Madame Bubble, a witch whose enchantments made the Enchanted Ground enchanted with an air that makes foolish pilgrims sleepy and never wake up again. She is the adulterous woman mentioned in the Biblical Book of Proverbs. Mr. Self-Will went over a bridge to meet her and never came back again.

Places in The Pilgrim's Progress

- City of Destruction, Christian's home, representative of the world (cf. Isaiah 19:18)

- Slough of Despond, the miry swamp on the way to the Wicket Gate; one of the hazards of the journey to the Celestial City. In the First Part, Christian falling into it, sank further under the weight of his sins (his burden) and his sense of their guilt.

- Mount Sinai, a frightening mountain near the Village of Morality that threatens all who would go there.

- Wicket Gate, the entry point of the straight and narrow way to the Celestial City. Pilgrims are required to enter by way of the Wicket Gate. Beelzebub's castle was built not very far from the Gate.

- House of the Interpreter, a type of spiritual museum to guide the pilgrims to the Celestial Ciblematic of Calvary and the tomb of Christ.

- Hill Difficulty, both the hill and the road up is called "Difficulty"; it is flanked by two treacherous byways "Danger" and "Destruction." There are three choices: Christian takes "Difficulty" (the right way), and Formalist and Hypocrisy take the two other ways, which prove to be fatal dead ends.

- House Beautiful, a palace that serves as a rest stop for pilgrims to the Celestial City. It apparently sits atop the Hill Difficulty. From the House Beautiful one can see forward to the Delectable Mountains. It represents the Christian congregation, and Bunyan takes its name from a gate of the Jerusalem temple (Acts 3:2, 10).

- Valley of Humiliation, the Valley on the other side of the Hill Difficulty, going down into which is said to be extremely slippery by the House Beautiful's damsel Prudence. It is where Christian, protected by God's Armor, meets Apollyon and they had that dreadful, long fight where Christian was victorious over his enemy by impaling Apollyon on his Sword of the Spirit (Word of God) which caused the Foul Fiend to fly away. Apollyon met Christian in the place known as "Forgetful Green." This Valley had been a delight to the "Lord of the Hill", Jesus Christ, in his "state of humiliation."

- Valley of the Shadow of Death, a treacherous, devilish Valley filled with demons, dragons, fiends, satyrs, goblins, hobgoblins, monsters, creatures from the bottomless pit, beasts from the mouth of Hell, darkness, terror, and horror with a quick sand bog on one side and a deep chasm/ditch on the other side of the King's Highway going through it (cf. Psalm 23:4).

- Gaius' Inn, a rest stop in the Second Part of the Pilgrim's Progress.

- Vanity Fair, a city through which the King's Highway passes and the yearlong Fair that is held there.

- Plain Ease, a pleasant area traversed by the pilgrims.

- Hill Lucre, location of a reputed silver mine that proves to be the place where By-Ends and his companions are lost.

- The Pillar of Salt, which was Lot's wife, who was turned into a pillar of salt when Sodom and Gomorrah were destroyed. The pilgrim's note that its location near the Hill Lucre is a fitting warning to those who are tempted by Demas to go into the Lucre silver mine.

- River of God or River of the Water of Life, a place of solace for the pilgrims. It flows through a meadow, green all year long and filled with lush fruit trees. In the Second Part the Good Shepherd is found there to whom Christiana's grandchildren are entrusted.

- By-Path Meadow, the place leading to the grounds of Doubting Castle.

- Doubting Castle, the home of Giant Despair and his Giantess wife, Diffidence; only one key could open its doors and gates, the key Promise.

- The Delectable Mountains, known as "Immanuel's Land." Lush country from whose heights one can see many delights and curiosities. It is inhabited by sheep and their shepherds, and from Mount Clear one can see the Celestial City.

- The Enchanted Ground, an area through which the King's Highway passes that has air that makes pilgrims want to stop to sleep. If one goes to sleep in this place, one never wakes up. The shepherds of the Delectable Mountains warn pilgrims about this.

- The Land of Beulah, a lush garden area just this side of the River of Death.

- The River of Death, the dreadful river that surrounds Mount Zion, deeper or shallower depending on the faith of the one traversing it.

- The Celestial City, the "Desired Country" of pilgrims, heaven, the dwelling place of the "Lord of the Hill", God. It is situated on Mount Zion.

Geographical and topographical features behind the fictional places

Scholars have pointed out that Bunyan may have been influenced in the creation of places in The Pilgrim's Progress by his own surrounding environment. Albert Foster[17] describes the natural features of Bedfordshire that apparently turn up in The Pilgrim's Progress. Vera Brittain in her thoroughly researched biography of Bunyan,[18] identifies seven locations that appear in the allegory. Other connections are suggested in books not directly associated with either John Bunyan or The Pilgrim's Progress.

At least twenty-one natural or man-made geographical or topographical features from The Pilgrim's Progress have been identified—places and structures John Bunyan regularly would have seen as a child and, later, in his travels on foot or horseback. The entire journey from The City of Destruction to the Celestial City may have been based on Bunyan's own usual journey from Bedford, on the main road that runs less than a mile behind his Elstow cottage, through Ampthill, Dunstable and St Albans, to London.

In the same sequence as these subjects appear in The Pilgrim's Progress, the geographical realities are as follows:

- The plain (across which Christian fled) is Bedford Plain, which is fifteen miles wide with the town of Bedford in the middle and the river Ouse meandering through the northern half;

- The "Slough of Despond" (a major obstacle for Christian and Pliable: "a very miry slough") is the large deposits of gray clay, which supplied London Brick's works in Stewartby, which was closed in 2008. On either side of the Bedford to Ampthill road these deposits match Bunyan's description exactly. Presumably, the road was built on the "twenty thousand cart loads" of fill mentioned in The Pilgrim's Progress;[19] However, the area beside Elstow brook, where John grew up, may also have been an early inspiration - on the north side of this brook, either side of the path to Elstow was (and still is) boggy and John would have known to avoid straying off the main path.

- "Mount Sinai", the high hill on the way to the village of Morality, whose side "that was next the way side, did hang so much over,"[20] is the red, sandy, cliffs just north of Ridgmont (i.e. "Rouge Mont");

- The "Wicket Gate" could be the wooden gate at the entrance to the Elstow parish church[21] or the wicket gate (small door) in the northern wooden entrance door at the west end of Elstow Abbey Church.

- The castle, from which arrows were shot at those who would enter the Wicket Gate, could be the stand-alone belltower, beside Elstow Abbey church.

- The "House of the Interpreter" is the rectory of St John's church in the south side of Bedford, where Bunyan was mentored by the pastor John Gifford;

- The wall "Salvation" that fenced in the King's Highway coming after the House of the Interpreter[22] is the red brick wall, over four miles long, beside the Ridgmont to Woburn road, marking the boundary of the Duke of Bedford's estate;

- The "place somewhat ascending ... [with] a cross ... and a sepulchre"[22] is the village cross and well that stands by the church at opposite ends of the sloping main street of Stevington, a small village five miles west of Bedford. Bunyan would often preach in a wood by the River Ouse just outside the village.

- The "Hill Difficulty" is Ampthill Hill, on the main Bedford road, the steepest hill in the county. A sandy range of hills stretches across Bedfordshire from Woburn through Ampthill to Potton. These hills are characterized by dark, dense and dismal woods reminiscent of the byways "Danger" and "Destruction", the alternatives to the way "Difficulty" that goes up the hill;[23]

- The pleasant arbour on the way up the Hill Difficulty is a small "lay-by", part way up Ampthill Hill, on the east side. A photo, taken in 1908, shows a cyclist resting there;[24]

- The "very narrow passage" to the "Palace Beautiful"[25] is an entrance cut into the high bank by the roadside to the east at the top of Ampthill Hill;

- The "Palace Beautiful" is Houghton (formerly Ampthill) House, built in 1621 but a ruin since 1800. The house faced north; and, because of the dramatic view over the Bedford plain, it was a popular picnic site during the first half of the twentieth century when many families could not travel far afield;.[26] The tradesman's entrance was on the south side looking out over the town of Ampthill and towards the Chilterns, the model of "The Delectable Mountains". There is also an earlier source of inspiration; As a young boy, John would have regularly seen, and been impressed by, "Elstow Place" - the grand mansion behind Elstow Church, built for Sir Thomas Hillersden from the cloister buildings of Elstow Abbey.

- The "Valley of the Shadow of Death" is Millbrook gorge to the west of Ampthill;

- "Vanity Fair" is probably also drawn from a number of sources. Some argue that local fairs in Elstow, Bedford and Ampthill were too small to fit Bunyan's description [27] but Elstow's May fairs are known to have been large and rowdy and would certainly have made a big impression on the young Bunyan. Stourbridge Fair, held in Cambridge during late August and early September fits John Bunyan's account of the fair's antiquity and its vast variety of goods sold[28] and sermons were preached each Sunday during Stourbridge Fair in an area called the "Dodderey." John Bunyan preached often in Toft, just four miles west of Cambridge, and there is a place known as "Bunyan's Barn" in Toft,[29] so it is surmised that Bunyan visited the notable Stourbridge Fair;

- The "pillar of salt", Lot's wife,[30] is a weather-beaten statue that looks much like person-sized salt pillar. It is located on small island in the river Ouse just north of Turvey bridge, eight miles west of Bedford near Stevington;

- The "River of the Water of Life", with trees along each bank[31] is the river Ouse east of Bedford, where John Bunyan as a boy would fish with his sister Margaret. It might also be the valley of river Flit, flowing through Flitton and Flitwick south of Ampthill;

- "Doubting Castle" is Ampthill Castle, built in the early 15th century and often visited by King Henry VIII as a hunting lodge. Henry, corpulent and dour, may have been considered by Bunyan to be a model for Giant Despair. Amphill Castle was used for the "house arrest" of Queen Catherine of Aragon and her retinue in 1535-36 before she was taken to Kimbolton. The castle was dismantled soon after 1660, so Bunyan could have seen its towers in the 1650s and known of the empty castle plateau in the 1670s[32] Giant Despair was killed and Doubting Castle was demolished in the second part of The Pilgrim's Progress.[33]

- The "Delectable Mountains" are the Chiltern Hills that can be seen from the second floor of Houghton House. "Chalk hills, stretching fifty miles from the Thames to Dunstable Downs, have beautiful blue flowers and butterflies, with glorious beech trees."[34] Reminiscent of the possibility of seeing the Celestial City from Mount Clear,[35] on a clear day one can see London's buildings from Dunstable Downs near Whipsnade Zoo;

- The "Land of Beulah" is Middlesex county north and west of London, which had pretty villages, market gardens, and estates containing beautiful parks and gardens): "woods of Islington to the green hills of Hampstead & Highgate";[36]

- The "very deep river"[37] is the River Thames, one thousand feet wide at high tide; however, in keeping with Bunyan's route to London, the river would be to the north of the city;

- The "Celestial City" is London, the physical centre of John Bunyan's world—most of his neighbours never travelled that far. In the 1670s, after the Great Fire of 1666, London sported a new, gleaming, city centre with forty churches.[38] In the last decade of Bunyan's life (1678–1688) some of his best Christian friends lived in London, including a Lord Mayor.

Cultural influence

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: John Bunyan |

The allegory of this book has antecedents in a large number of Christian devotional works that speak of the soul's path to Heaven, from the Lyke-Wake Dirge forward. Bunyan's allegory stands out above his predecessors because of his simple and effective prose style, steeped in Biblical texts and cadences. He confesses his own naïveté in the verse prologue to the book:

- "I did not think

To shew to all the World my Pen and Ink

In such a mode; I only thought to make

I knew not what: nor did I undertake

Thereby to please my Neighbour; no not I;

I did it mine own self to gratifie."

Bunyan's inspiration? Due to many similarities - some more definite than others - it could be argued that he had access to Dante's Commedia. The Pilgrim's Progress may therefore be a distillation of the entire 'pilgrimage' that the 14th Century Italian penned.

Because of the widespread longtime popularity of The Pilgrim's Progress, Christian's hazards — whether originally from Bunyan or borrowed by him from the Bible—the "Slough of Despond", the "Hill Difficulty", "Valley of the Shadow of Death", "Doubting Castle", and the "Enchanted Ground", his temptations (the wares of "Vanity Fair" and the pleasantness of "By-Path Meadow"), his foes ("Apollyon" and "Giant Despair"), and the helpful stopping places he visits (the "House of the Interpreter", the "House Beautiful", the "Delectable Mountains", and the "Land of Beulah") have become commonly used phrases proverbial in English. For example, "One has one's own Slough of Despond to trudge through."

Context in Christendom

The explicit Protestant theology of The Pilgrim's Progress made it much more popular than its predecessors. Bunyan's plain style breathes life into the abstractions of the anthropomorphized temptations and abstractions that Christian encounters and with whom he converses on his course to Heaven. Samuel Johnson said that "this is the great merit of the book, that the most cultivated man cannot find anything to praise more highly, and the child knows nothing more amusing." Three years after its publication (1681), it was reprinted in colonial America, and was widely read in the Puritan colonies.

Because of its explicit English Protestant theology The Pilgrim's Progress shares the then popular English antipathy toward the Roman Catholic Church. It was published over the years of the Popish Plot (1678–1681) and ten years before the Glorious Revolution of 1688, and it shows the influence of John Foxe's Acts and Monuments. Bunyan presents a decrepit and harmless giant to confront Christian at the end of the Valley of the Shadow of Death that is explicitly named "Pope":

Now I saw in my Dream, that at the end of this Valley lay blood, bones, ashes, and mangled bodies of men, even of Pilgrims that had gone this way formerly: And while I was musing what should be the reason, I espied a little before me a Cave, where two Giants, Pope and Pagan, dwelt in old times, by whose Power and Tyranny the Men whose bones, blood ashes, &c. lay there, were cruelly put to death. But by this place Christian went without much danger, whereat I somewhat wondered; but I have learnt since, that Pagan has been dead many a day; and as for the other, though he be yet alive, he is by reason of age, and also of the many shrewd brushes that he met with in his younger dayes, grown so crazy and stiff in his joynts, that he can now do little more than sit in his Caves mouth, grinning at Pilgrims as they go by, and biting his nails, because he cannot come at them.[39]

When Christian and Faithful travel through Vanity Fair, Bunyan adds the editorial comment:

But as in other fairs, some one Commodity is as the chief of all the fair, so the Ware of Rome and her Merchandize is greatly promoted in this fair: Only our English Nation, with some others, have taken a dislike thereat.[40]

In the Second Part while Christiana and her group of pilgrims led by Greatheart stay for some time in Vanity, the city is terrorized by a seven-headed beast[41] which is driven away by Greatheart and other stalwarts.[42] In his endnotes W.R. Owens notes about the woman that governs the beast: "This woman was believed by Protestants to represent Antichrist, the Church of Rome. In a posthumously published treatise, Of Antichrist, and his Ruine (1692), Bunyan gave an extended account of the rise and (shortly expected) fall of Antichrist."[43]

Foreign language versions

Beginning in the 1850s, illustrated versions of The Pilgrim's Progress in Chinese were printed in Hong Kong, Shanghai and Fuzhou and widely distributed by Protestant missionaries. Hong Xiuquan, the quasi-Christian leader of the Taiping Rebellion, declared that the book was his favorite reading.[44]

Little did the missionaries who distributed The Pilgrim's Progress know that the foreigners would appropriate it to make sense of their own experiences. Heaven was often a place designed to resemble what they had gone through in life. For example, in South Africa, a version was written where the injustices which took place in that country were reformulated.[45]

There are collections of old foreign language versions of The Pilgrim's Progress at both Elstow's Moot Hall museum, and at the John Bunyan Museum in Mill Street Bedford.

The "Third Part"

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

The Third Part of the Pilgrim's Progress was written by an anonymous author; beginning in 1693, it was published with Bunyan's authentic two parts. It continued to be republished with Bunyan's work until 1852.[46] This third part presented the pilgrimage of Tender-Conscience and his companions.

Dramatic and musical settings

The book was the basis of a condensed radio adaptation, originally presented in 1942 and starring John Gielgud, which included, as background music, several excerpts from Vaughan Williams' orchestral works.

The book was the basis of an The Pilgrim's Progress (opera) by Ralph Vaughan Williams, premiered in 1951.

The radio version was newly recorded by Hyperion Records in 1990, in a performance conducted by Matthew Best. It again starred Gielgud, and featured Richard Pasco and Ursula Howells.

English composer Ernest Austin set the whole story as a huge narrative tone poem for solo organ, with optional 6-part choir and narrator, lasting approximately 2½ hours.

Under the name The Similitude of a Dream, the progressive rock band of Neal Morse released a concept album based on The Pilgrim's Progress in November 2016.

References in literature

Charles Dickens' book Oliver Twist (1838) is subtitled 'The Parish Boy's Progress'.

The title of William Makepeace Thackeray's 1847–8 novel Vanity Fair alludes to the location in Bunyan's work.

Mark Twain gave his 1869 travelogue, The Innocents Abroad, the alternate title The New Pilgrims' Progress. In Twain's later work Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, the titular character mentions The Pilgrim's Progress as he describes the works of literature in the Grangerfords' library. Twain uses this to satirize the Protestant southern aristocracy.

E. E. Cummings makes numerous references to it in his prose work, The Enormous Room.

Nathaniel Hawthorne's short story, "The Celestial Railroad", recreates Christian's journey in Hawthorne's time. Progressive thinkers have replaced the footpath by a railroad, and pilgrims may now travel under steam power. The journey is considerably faster, but somewhat more questionable.

John Buchan was an admirer of Bunyan's, and Pilgrim's Progress features significantly in his third Richard Hannay novel, Mr Standfast, which also takes its title from one of Bunyan's characters.

Alan Moore, in his League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, enlists The Pilgrim's Progress protagonist, Christian, as a member of the earliest version of this group, Prospero's Men, having become wayward on his journey during his visit in Vanity Fair, stepping down an alleyway and found himself in London in the 1670s, and unable to return to his homeland. This group disbanded in 1690 after Prospero vanished into the Blazing World; however, some parts of the text seem to imply that Christian resigned from Prospero's league before its disbanding and that Christian traveled to the Blazing World before Prospero himself. The apparent implication is that; within the context of the League stories; the Celestial City Christian seeks and the Blazing World may in fact be one and the same.

In Louisa May Alcott's Little Women, the protagonist Jo and her sisters read it at the outset of the novel, and try to follow the good example of Bunyan's Christian. Throughout the novel, the main characters refer many times to Pilgrim's Progress and liken the events in their own lives to the experiences of the pilgrims. A number of chapter titles directly reference characters and places from Pilgrim's Progress.

The cartoonist Winsor McCay drew an allegorical comic strip, entitled "A Pilgrim's Progress", in the New York Evening Telegram. The strip ran from 26 June 1905 to 18 December 1910. In it, the protagonist Mr. Bunion is constantly frustrated in his attempts to improve his life by ridding himself of his burdonsome valise, "Dull Care".[47]

C. S. Lewis wrote a book inspired by The Pilgrim's Progress, called The Pilgrim's Regress, in which a character named John follows a vision to escape from The Landlord, a less friendly version of The Owner in The Pilgrim's Regress. It is an allegory of C. S. Lewis' own journey from a religious childhood to a pagan adulthood in which he rediscovers his Christian God.

Henry Williamson's The Patriot's Progress references the title of The Pilgrim's Progress and the symbolic nature of John Bunyan's work. The protagonist of the semi-autobiographical novel is John Bullock, the quintessential English soldier during World War I.

The character of Billy Pilgrim in Kurt Vonnegut's novel, Slaughterhouse-5: The Children's Crusade, is a clear homage to a similar journey to enlightenment experienced by Christian, although Billy's journey leads him to an existential acceptance of life and of a fatalist human condition. Vonnegut's parallel to The Pilgrim's Progress is deliberate and evident in Billy's surname.

Charlotte Brontë refers to Pilgrim's Progress in most of her novels, including Jane Eyre,[48] Shirley,[49] and Villette.[50] Her alterations to the quest-narrative have led to much critical interest, particular with the ending of Jane Eyre.[51]

Walt Willis and Bob Shaw's classic science fiction fan novelette, The Enchanted Duplicator, is explicitly modeled on The Pilgrim's Progress and has been repeatedly reprinted over the decades since its first appearance in 1954: in professional publications, in fanzines, and as a monograph.

Enid Blyton wrote The Land of Far Beyond (1942) as a children's version of The Pilgrim's Progress.

John Steinbeck's novel The Grapes of Wrath mentions The Pilgrim's Progress as one of an (anonymous) character's favorite books. Steinbeck's novel was itself an allegorical spiritual journey by Tom Joad through America during the Great Depression, and often made Christian allusions to sacrifice and redemption in a world of social injustice.

The book was commonly referenced in African American slave narratives, such as "Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom" by Ellen and William Craft, to emphasize the moral and religious implications of slavery.[52]

Hannah Hurnard's novel Hinds' Feet on High Places (1955) uses a similar allegorical structure to The Pilgrim's Progress and takes Bunyan's character Much Afraid as its protagonist.

Dramatizations, music, and film

- In 1850, a moving panorama of Pigrim's Progress, known as the Bunyan Tableuax or the Grand Moving Panorama of Pilgrim's Progress was painted by Joseph Kyle and Edward Harrison May and displayed in New York; an early copy of this panorama survives and is at the Saco Museum in Maine.

- The novel was made into a film, Pilgrim's Progress, in 1912.[53]

- In 1950 an hour-long animated version was made by Baptista Films. This version was edited down to 35 minutes and re-released with new music in 1978. As of 2007 the original version is difficult to find, but the 1978 has been released on both VHS and DVD.[54]

- In 1951 First performance of the opera "The Pilgrim's Progress", composed by Ralph Vaughan Williams, at the Royal Opera of Covent Garden

- In 1978, another film version was made by Ken Anderson, in which Liam Neeson played the role of the Evangelist [55] and other smaller roles like the crucified Christ. Maurice O'Callaghan played the Pilgrim,[55] and Peter Thomas played Worldly Wiseman.[55] A sequel Christiana followed later.

In 1978 a musical based loosely on Bunyan's characters and the story was written by Nick Taylor and Alex Learmont. The musical [originally titled "Pilgrim"] was produced for the Natal Performing Arts Council under the title "CHRISTIAN!" or FOLLOW THE MAN WITH THE BIG BASS DRUM IN THE HOLY GLORY BAND, and ran to capacity houses for the 1979/80 summer season in Durban's old Alhambra Theatre. The show moved to Johannesburg in March 1980 and ran for a further three months at His Majesty's Theatre. After a substantial re-write CHRISTIAN! was again mounted at the new Playhouse in Durban for the 1984 Christmas season. The musical has been performed many times since by schools and amateur theatrical groups in South Africa. After 30 years the show is again attracting attention both locally and abroad and the score and libretto are being updated and made more flexible for large and small productions.[56]

- In 1985 Yorkshire Television produced a 129-minute 9-part serial presentation of The Pilgrim's Progress with animated stills by Alan Parry and narrated by Paul Copley entitled Dangerous Journey.

- In 1989, Orion's Gate, a producer of Biblical/Spiritual audio dramas produced The Pilgrim's Progress as a 6-hour audio dramatization.[57] This production was followed several years later by Christiana: Pilgrim's Progress Part II, another 8 hour audio dramatization.

- In 1993, the popular Christian radio drama, Adventures in Odyssey (produced by Focus on the Family), featured a two-part story, titled "Pilgrim's Progress: Revisited."

- In 1993, the game Doom (1993 video game) was released by id Software, and featured a map called "Slough of Despair" (E3M2: episode 3, map 2).

- In 1994, "The Pilgrim's Progress" and the imprisonment of John Bunyan were the subject of the musical Celestial City[58] by David MacAdam, with John Curtis, and an album was released in 1997.

- In 2003 the game Heaven Bound was released by Emerald Studios. The 3D adventure-style game, based on the novel, was only released for the PC.[59]

- A 2005 computer animation version was made, directed and narrated by Scott Cawthon, today noted as being developer of the popular indie horror video game Five Nights at Freddy's. Cawthon has also produced a video game adaptation.

- In 2008, a version by Danny Carrales,Pilgrim's Progress: Journey to Heaven, was produced.

- At the 2009 San Antonio Independent Christian Film Festival, the adaptation Pilgrim's Progress: Journey to Heaven received one nomination for best feature length independent film and one nomination for best music score.

- British music band Kula Shaker released an album called Pilgrim's Progress on 28 June 2010.

- In 2003 Michael W. Smith wrote a song, called Signs, which he says on his A 20 Year Celebration live DVD to be inspired by the Pilgrim's Progress.

- Jim Winder (www.Jim-Winder.com) performs a live telling of Pilgrim's Progress (the first part) with contemporary Christian songs based on the story line and Biblical content.[60]

- Season 7, episode 16 of Family Guy (17 May 2009) is a parody of The Pilgrim's Progress "Peter's Progress."[61]

- In 2010, FishFlix.com released the Ambassador Films production A Pilgrim's Progress - The Story of John Bunyan to DVD. A documentary about Bunyan's life, filmed on location in England and narrated by Derick Bingham.[62]

- In 2013, Puritan Productions[63] company announced the premiere of its dramatization with ballet & chorus accompaniment in Fort Worth, Texas at the W.E. Scott Theatre[64] on 18–19 October

- In 2014, a Kickstarter supported novel called The Narrow Road was published. It is based on The Pilgrim's Progress, and was written by Erik Yeager and illustrated by Dave delaGardelle.

- In 2014, Puritan Productions company announced its second showing of their dramatization of the book, with ballet & chorus accompaniment. This time, in Garland, Texas at the Granville Arts Center on 24, 25 and 26 October.

- In March, 2015 Director Darren Wilson announced a Kickstarter campaign to produce a full-length feature film based on The Pilgrims Progress called Heaven Quest: A Pilgrim's Progress Movie.[65]

- The Neal Morse Band released their 2nd album titled The Similitude of a Dream on 11/11/2016, a 2-CD concept album based on the book The Pilgrim's Progress.

- In 2016, Puritan Productions company announced its showing of their dramatization of the book, with ballet & chorus accompaniment in Austin, Texas at Park Hills Baptist Church on 4 and 5 November

Editions

- Bunyan, John The Pilgrim's Progress. Edited by Roger Sharrock and J. B. Wharey. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1975) [ISBN 0198118023]. The standard critical edition, originally published in 1928 and revised in 1960 by Sharrock.[66]

- Bunyan, John The Pilgrim's Progress. Edited with an introduction and notes by Roger Sharrrock. (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1987) [ISBN 0140430040]. The text is based on the 1975 Clarendon edition (see above), but with modernised spelling and punctuation 'to meet the needs of the general reader'.[66]

- Bunyan, John The Pilgrim's Progress. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003) [ISBN 978-0-19-280361-0].

Abridged editions

- The Children's Pilgrim's Progress. The story taken from the work by John Bunyan. New York: Sheldon and Company, 1866.

Retellings

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- "The Aussie Pilgrim's Progress" by Kel Richards. Ballarat: Strand Publishing, 2005.

- John Bunyan's Dream Story: the Pilgrim's Progress retold for children and adapted to school reading by James Baldwin. New York: American Book Co., 1913.

- John Bunyan's Pilgrim's Progress as retold by Gary D. Schmidt & illustrated by Barry Moser Published by William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, Grand Rapids, Michigan. Copyright 1994.

- The Evergreen Wood: An Adaptation of the "Pilgrim's Progress" for Children written by Linda Perry, illustrated by Alan Perry. Published by Hunt & Thorpe, 1997.

- The Land of Far-Beyond by Enid Blyton. Methuen, 1942.

- Little Pilgrim's Progress - Helen L. Taylor simplifies the vocabulary and concepts for younger readers, while keeping the story line intact. Published by Moody Press, a ministry of Moody Bible Institute, Chicago, Illinois, 1992, 1993.

- Pilgrim's Progress (graphic novel by Marvel Comics). Thomas Nelson, 1993.

- Pilgrim's Progress, from This World to That Which Is to Come. Rev., 2nd ed., in modern English - Christian Literature Crusade, Fort Washington, Penn., 1981. Without ISBN

- The Pilgrim's Progress - A 21st Century Re-telling of the John Bunyan Classic - Dry Ice Publishing, 2008 directed by Danny Carrales[67]

- The Pilgrim's Progress by John Bunyan Every Child Can Read. Edited by Jesse Lyman Hurlbut. Philadelphia: The John C. Winston Co., 1909.

- Pilgrim's Progress in Today's English - as retold by James H. Thomas. Moody Publishers. 1971. LCCN 64-25255.

- The Pilgrim's Progress in Words of One Syllable by Mary Godolphin. London: George Routledge and Sons, 1869.

- Pilgrim's Progress retold and shortened for modern readers by Mary Godolphin (1884). Drawings by Robert Lawson. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Co., 1939. [a newly illustrated edition of the retelling by Mary Godolphin]

- The New Amplified Pilgrim's Progress (both book and dramatized audio) - as retold by James Pappas. Published by Orion's Gate (1999). A slightly expanded and highly dramatized version of John Bunyan's original. Large samples of the text are available[57]

- "Quest for Celestia: A Reimagining of The Pilgrim's Progress" by Steven James, 2006

- Stephen T. Moore (2011). "The Pilgrim's Progress" A very graphic novel. 150. ISBN 978-1461032717.

References

- ↑ "The two parts of The Pilgrim's Progress in reality constitute a whole, and the whole is, without doubt, the most influential religious book ever written in the English language" (Alexander M. Witherspoon in his introduction, John Bunyan, The Pilgrim's Progress (New York: Pocket Books, 1957), vi.

- ↑ John Bunyan, The Pilgrim's Progress, W.R. Owens, ed., Oxford World's Classics (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003), xiii.

- ↑ Abby Sage Richardson, Familiar Talks on English Literature: A Manual (Chicago, A.C. McClurg & Co., 1892), 221.

- ↑ "For two hundred years or more no other English book was so generally known and read" (James Baldwin in his foreword, James Baldwin, John Bunyan's Dream Story (New York: American Book Co., 1913), 6).

- ↑ John Bunyan, The Pilgrim's Progress, W.R. Owens, ed., Oxford World's Classics (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003), xiii: "...the book has never been out of print. It has been published in innumerable editions, and has been translated into over two hundred languages."

- ↑ F.L. Cross, ed., The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1983), 1092 sub loco.

- ↑ John Brown, John Bunyan: His Life, Times and Work, (1885, revised edition 1928)

- 1 2 3 4 5 John Bunyan, The Pilgrim's Progress, edited with an introduction by Roger Sharrock, (Harmondsworth: Penguins Books, Ltd., 1965), 10, 59, 94, 326-27, 375.

- ↑ "The copy for the first edition of the First Part of The Pilgrim's Progress was entered in the Stationers' Register on 22 December 1677 ... The book was licensed and entered in the Term Catalogue for the following Hilary Term, 18 February 1678; this date would customarily indicate the time of publication, or only slightly precede it" [John Bunyan, The Pilgrim's Progress, James Blanton Wharey and Roger Sharrock, eds., Second Edition, (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1960), xxi].

- ↑ 2 Peter 1:19: "a lamp shining in a dark place"

- ↑ Go to section 1.2.3.1 Mr. Sagacity leaves the author

- ↑ A marginal note indicates, "There is no deliverance from the guilt and burden of sin, but by the death and blood of Christ" cf. Sharrock, page 59.

- ↑ "Many of the pictures in the House of the Interpreter seem to be derived from emblem books or to be created in the manner and spirit of the emblem. ... Usually each emblem occupied a page, and consisted of an allegorical picture at the top with underneath it a device or motto, a short Latin verse, and a poem explaining the allegory. Bunyan himself wrote an emblem book, A Book for Boys and Girls (1688) ...", cf. Sharrock, p. 375.

- ↑ "the whole armour (panoply) of God"

- ↑ "the whole armour (panoply) of God"

- ↑ John Bunyan, The Pilgrim's Progress, (New York: Pocket Books, Inc., 1957), vi.

- ↑ Albert J. Foster, Bunyan's Country: Studies in the Topography of Pilgrim's Progress, (London: H. Virtue, 1911)

- ↑ Vera Brittain. "In the Steps of John Bunyan". London: Rich & Cowan, 1949. Retrieved 2012-10-28.

- ↑ John Bunyan, The Pilgrim's Progress, W.R. Owens, ed., (Oxford: University Press, 2003), 17

- ↑ John Bunyan, The Pilgrim's Progress, W.R. Owens, ed., (Oxford: University Press, 2003), 20.

- ↑ See article on John Bunyan

- 1 2 John Bunyan, The Pilgrim's Progress, W.R. Owens, ed., (Oxford: University Press, 2003), 37.

- ↑ John Bunyan, The Pilgrim's Progress, W.R. Owens, ed., (Oxford: University Press, 2003), 41-42.

- ↑ A. Underwood, Ampthill in old picture postcards, (Zaltbommel, Netherlands: European Library, 1989).

- ↑ John Bunyan, The Pilgrim's Progress, W.R. Owens, ed., (Oxford: University Press, 2003), 45.

- ↑ A. Underwood, Ampthill in Old Picture Cards, (Zaltbommel, Netherlands: European Library, 1989)

- ↑ John Bunyan, The Pilgrim's Progress, W.R. Owens, ed., (Oxford: University Press, 2003), 85-86.

- ↑ E. South and O. Cook, Prospect of Cambridge, (London: Batsford, 1985).

- ↑ Vera Brittain, In the Steps of John Bunyan, (London: Rich & Cowan, 1949)

- ↑ John Bunyan, The Pilgrim's Progress, W.R. Owens, ed., (Oxford: University Press, 2003), 105.

- ↑ John Bunyan, The Pilgrim's Progress, W.R. Owens, ed., (Oxford: University Press, 2003), 107.

- ↑ A.J. Foster, Ampthill Towers, (London: Thomas Nelson, 1910).

- ↑ John Bunyan, The Pilgrim's Progress, W.R. Owens, ed., (Oxford: University Press, 2003), 262-264.

- ↑ J. Hadfield, The Shell Guide to England, (London: Michael Joseph, 1970)

- ↑ John Bunyan, The Pilgrim's Progress, W.R. Owens, ed., (Oxford: University Press, 2003), 119.

- ↑ E. Rutherfurd, London: The Novel, (New York: Crown Publishers, 1997).

- ↑ John Bunyan, The Pilgrim's Progress, W.R. Owens, ed., (Oxford: University Press, 2003), 147.

- ↑ H.V. Morton, In Search of London, (London: Methuen & Co., 1952)

- ↑ John Bunyan, The Pilgrim's Progress, W.R. Owens, ed., Oxford World's Classics (Oxford: University Press, 2003), 66, 299.

- ↑ John Bunyan, The Pilgrim's Progress, W.R. Owens, ed., Oxford World's Classics (Oxford: University Press, 2003), 86, 301.

- ↑ Revelation 17:1-18.

- ↑ John Bunyan, The Pilgrim's Progress, W.R. Owens, ed., Oxford World's Classics (Oxford: University Press, 2003), 258-59.

- ↑ John Bunyan, The Pilgrim's Progress, W.R. Owens, ed., Oxford World's Classics (Oxford: University Press, 2003), 318: "See Misc. Works, xiii. 421-504."

- ↑ Jonathan D. Spence, God's Chinese Son, 1996. p. 280-282

- ↑ Hofmeyr, I. (2002). Dreams, Documents and 'Fetishes': African Christian Interpretations of The Pilgrim's Progress. Journal of Religion In Africa, 32(4), 440-455.

- ↑ "A third part falsely attributed to Bunyan appeared in 1693, and was reprinted as late as 1852," (New Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia, vol. 2 under "John Bunyan")

- ↑ Canemaker, John (1987), Winsor McCay: His Life and Art, Cross River Press, New York

- ↑ Brontë, Charlotte. Jane Eyre. Ed. Richard J. Dunn. WW Norton: 2001. p. 385.

- ↑ Brontë, Charlotte. Shirley. Oxford University Press: 2008. p. 48, 236.

- ↑ Brontë, Charlotte. Villette. Ed. Tim Dolin. Oxford University Press: 2008, p. 6, 44.

- ↑ Beaty, Jerome. "St. John's Way and the Wayward Reader". Brontë, Charlotte. Jane Eyre. Ed. Richard J. Dunn. WW Norton: 2001. 491-503. p. 501

- ↑ Gould, Philip (2007). Audrey Fisch, ed. The Cambridge Companion to the African American Slave Narrative. New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 20–21. ISBN 978-0-521-85019-3.

- ↑ "The Pilgrim's Progress (1912)". IMDb.com. Retrieved 2012-10-28.

- ↑ "A Brief History of Christian Film: 1918-2002". Avgeeks.com. Retrieved 2012-10-28.

- 1 2 3 "The Mystical Movie Guide". Astralresearch.org. Retrieved 2012-10-28.

- ↑ Nick Taylor [singer/songwriter] & Alex Learmont [film maker and lyricist]

- 1 2 "Orion's Gate - Dramatized Pilgrim's Progress and More!". Orionsgate.org. 2007-11-06. Retrieved 2012-10-28.

- ↑ "Celestial City". New Life Fine Arts. 2012-10-07. Retrieved 2012-10-28.

- ↑ "Heaven Bound | Video Game Information, Trailers, Screenshots". CEGAnMo.com. Retrieved 2012-10-28.

- ↑ "Journey to the Celestial City".

- ↑ ""Family Guy" Peter's Progress (TV Episode 2009)". IMDb. 17 May 2009.

- ↑ "Christian Movies Store - FishFlix.com".

- ↑ "Puritan Productions".

- ↑ "Fort Worth Community Arts Center".

- ↑ "HeavenQuest: A Pilgrim's Progress Movie". Kickstarter.

- 1 2 Bunyan, John (1987). Sharrock, Roger, ed. The Pilgrim's Progress (3 ed.). Harmondsworth: Penguin. p. 29. ISBN 0140430040.

- ↑ "Pilgrim's Progress (2008)". Imdb.bom. Retrieved 2012-10-28.

See also

- The Conference of the Birds - a Muslim work using a similar device of an allegorical journey

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pilgrim's Progress. |

-

The Pilgrim's Progress public domain audiobook at LibriVox

The Pilgrim's Progress public domain audiobook at LibriVox - Journey to the Celestial City

- The Pilgrim's Progress (Project Gutenberg etext)

- The Pilgrim's Progress: parts I & II. (Ebook, PDF layout and fonts inspired by 18th century publications

- Voyage du pèlerin PDF Ebook - French translation of The Pilgrim's Progress

- The Pilgrim's Progress - graphic novel (FREE PDF DOWNLOAD)