Platynereis dumerilii

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Platynereis dumerilii. |

| Platynereis dumerilii | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Annelida |

| Class: | Polychaeta |

| Order: | Phyllodocida |

| Family: | Nereididae |

| Genus: | Platynereis |

| Species: | P. dumerilii |

| Binomial name | |

| Platynereis dumerilii (Audouin & Milne-Edwards, 1834[1]) | |

Platynereis dumerilii belongs to the Annelids.[2] It was originally placed into the genus Nereis[1] and later reassigned to Platynereis.[3] Platynereis dumerilii lives in coastal marine waters from temperate to tropical zones. It can be found in a wide range from the Azores, the Mediterranean, in the North Sea, the English Channel, and the Atlantic down to the Cape of Good Hope, in the Black Sea, the Red Sea, the Persian Gulf, the Sea of Japan, the Pacific, and the Kerguelen Islands.[3] Platynereis dumerilii is today an important lab animal,[4] it is considered as a living fossil, and it is used in many phylogenetic studies as a model organism. Platynereis dumerilii reaches an age of 3 to 18 month[4] and males reach a length of 2 to 3 cm, while females reach a length of 3 to 4 cm.[5]

Reproduction and Development

Platynereis dumerilii is dioecious, that means it has two separate sexes:[6] During mating, the male swims around the female while the female is swimming in small circles. Both release eggs and sperm into the water. This is triggered by sexual pheromones. The eggs are then fertilized outside of the body in the water.[7] Platynereis dumerilii has like other Nereidids no segmental gonades, the gametes mature freely swimming in the body cavity (coelom).[6]

Platynereis dumerilii develops very stereotypically between batches and therefore time can be used to stage Platynereis dumerilii larvae. However, the temperate influences the speed of development greatly.[8] Therefore, the following developmental times are given with 18 °C as reference temperature:

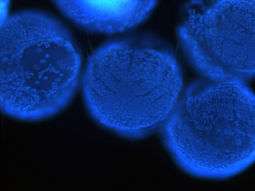

After 24 hours, a fertilized egg gives rise to a trochophore larva. At 48 hours, the trochophore larva becomes a metatrochophore larvae.[8] Both trochophore and metatrochophore swim with a ring of cilia in the water and are positively phototactic.[9] A day later, at 72 hours after fertilization, the metatrochophore larvae becomes a nectochaete larva. The nectochaete larva, already has three segments, each with a pair of parapodia bearing chaetae, which serve for locomotion.[8] The nectochaete larva can switch from positive to negative phototaxis.[10] After five to seven days, the larvae start feeding and develop on their own speed, depending on food supply. After three to four weeks, when six segments have formed, the head is formed.[8]

Photoreceptor Cells

Platynereis dumerilii larvae possess two kinds of photoreceptor cells: Rhabdomeric and ciliary photoreceptor cells.

The ciliary photoreceptor cells are located in the deep brain of the larva. They are not shaded by pigment and thus serve a non-directional light perception task. The ciliary photoreceptor cells resemble molecularly and morphologically the rods and cones of the human eye. Additional, they express an opsin that is more similar of vertebrate rod and cone visual ciliary opsins than those of invertebrate visual rhabdomeric opsins. Therefore, it is thought that the urbilaterain, the last common ancestor of mollusks, arthropods, and vertebrates already had ciliary photoreceptor cells.[11]

A rhabdomeric photoreceptor cell forms with a pigment cell a simple eye. A pair of these eyes mediate phototaxis in the early Platynereis dumerilii trochophore larva.[9] In the later nectochaete larva, phototaxis is mediated by the more complex adult eyes.[10] The adult eyes express at least three opsins: Two rhabdomeric opsins and a Go-opsin.[12][13] The three opsins there mediate phototaxis all the same way via depolarization,[13] even so a scallop Go-opsin is known to hyperpolarize.[14][15]

External links

References

- 1 2 Audouin, Jean Victoire; Milne-Edwards, Henri (1834). "Néréide de Dumeril. Nereis Dumerilii". Recherches pour servir a l'histoire naturelle du littoral de la France, ou, Recueil de mémoires sur l'anatomie, la physiologie, la classification et les moeurs des animaux des nos côtes : ouvrage accompagné de planches faites d'après nature. 2: 196–199. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.43796. Retrieved 7 October 2015.

- ↑ Read, G. "Platynereis dumerilii (Audouin & Milne Edwards, 1834). In: Read, G.; Fauchald, K. (Ed.) (2015)". World Register of Marine Species. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- 1 2 Fauvel, Pierre (1914). "Annélides polychètes non-pélagiques provenant des campagnes de l'Hirondelle et de la Princesse-Alice (1885-1910)". Résultats des campagnes scientifiques accompliés par le Prince Albert I. 46: 1–432.

- 1 2 Fischer, Albrecht; Dorresteijn, Adriaan (March 2004). "The polychaete Platynereis dumerilii (Annelida): a laboratory animal with spiralian cleavage, lifelong segment proliferation and a mixed benthic/pelagic life cycle". BioEssays. 26 (3): 314–325. doi:10.1002/bies.10409.

- ↑ Jha, A. N.; Hutchinson, T. H.; Mackay, J. M.; Elliott, B. M.; Pascoe, P. L.; Dixon, D. R. (1995). "The chromosomes Of Platynereis dumerilii (Polychaeta: Nereidae)". Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. 75 (03): 551. doi:10.1017/S002531540003900X.

- 1 2 Fischer, Albrecht (1999). "Reproductive and developmental phenomena in annelids: a source of exemplary research problems". Hydrobiologia. 402: 1–20. doi:10.1023/A:1003719906378.

- ↑ Zeeck, Erich; Harder, Tilman; Beckmann, Manfred (1998). "Uric acid: the sperm-release pheromone of the marine polychaete Platynereis dumerilii". Journal of Chemical Ecology. 24 (1): 13–22. doi:10.1023/A:1022328610423.

- 1 2 3 4 Fischer, Antje HL; Henrich, Thorsten; Arendt, Detlev (2010). "The normal development of Platynereis dumerilii (Nereididae, Annelida)". Frontiers in Zoology. 7 (1): 31. doi:10.1186/1742-9994-7-31.

- 1 2 Jékely, Gáspár; Colombelli, Julien; Hausen, Harald; Guy, Keren; Stelzer, Ernst; Nédélec, François; Arendt, Detlev (20 November 2008). "Mechanism of phototaxis in marine zooplankton". Nature. 456 (7220): 395–399. doi:10.1038/nature07590.

- 1 2 Randel, Nadine; Asadulina, Albina; Bezares-Calderón, Luis A; Verasztó, Csaba; Williams, Elizabeth A; Conzelmann, Markus; Shahidi, Réza; Jékely, Gáspár (27 May 2014). "Neuronal connectome of a sensory-motor circuit for visual navigation". eLife. 3. doi:10.7554/eLife.02730.

- ↑ Arendt, D.; Tessmar-Raible, K.; Snyman, H.; Dorresteijn, A.W.; Wittbrodt, J. (29 October 2004). "Ciliary Photoreceptors with a Vertebrate-Type Opsin in an Invertebrate Brain". Science. 306 (5697): 869–871. doi:10.1126/science.1099955.

- ↑ Randel, N.; Bezares-Calderon, L. A.; Gühmann, M.; Shahidi, R.; Jekely, G. (10 May 2013). "Expression Dynamics and Protein Localization of Rhabdomeric Opsins in Platynereis Larvae". Integrative and Comparative Biology. 53 (1): 7–16. doi:10.1093/icb/ict046.

- 1 2 Gühmann, Martin; Jia, Huiyong; Randel, Nadine; Verasztó, Csaba; Bezares-Calderón, Luis A.; Michiels, Nico K.; Yokoyama, Shozo; Jékely, Gáspár (August 2015). "Spectral Tuning of Phototaxis by a Go-Opsin in the Rhabdomeric Eyes of Platynereis". Current Biology. 25 (17): 2265–2271. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2015.07.017.

- ↑ Kojima, Daisuke; Terakita, Akihisa; Ishikawa, Toru; Tsukahara, Yasuo; Maeda, Akio; Shichida, Yoshinori (12 September 1997). "A Novel Go-mediated Phototransduction Cascade in Scallop Visual Cells". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 272 (37): 22979–82. doi:10.1074/jbc.272.37.22979. PMID 9287291.

- ↑ Gomez, MP; Nasi, E (15 July 2000). "Light transduction in invertebrate hyperpolarizing photoreceptors: possible involvement of a Go-regulated guanylate cyclase.". The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 20 (14): 5254–63. PMID 10884309.