Port Mann Bridge

| Port Mann Bridge (2012) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Coordinates | 49°13′16″N 122°48′46″W / 49.221031°N 122.812697°WCoordinates: 49°13′16″N 122°48′46″W / 49.221031°N 122.812697°W |

| Carries | Ten lanes of British Columbia Highway 1, pedestrians and bicycles |

| Crosses | Fraser River |

| Locale |

Coquitlam Surrey |

| Maintained by | Transportation Investment Corporation (TI Corp) |

| Preceded by | Port Mann Bridge (1964) |

| Characteristics | |

| Design | Cable-stayed bridge |

| Total length | 2,020 metres (6,630 ft) |

| Width | 65 metres (213 ft) |

| Height | 163 metres (535 ft) |

| Longest span | 470 metres (1,540 ft) |

| Clearance below | 42 metres (138 ft) |

| History | |

| Designer | T.Y. Lin International |

| Construction begin | February 2009 |

| Construction end | September 2015 |

| Construction cost | $820 million[1] |

| Opened | September 18, 2012 |

| References | |

| [2] | |

| Port Mann Bridge (1964) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Carries | Five lanes of British Columbia Highway 1 |

| Crosses | Fraser River |

| Locale |

Coquitlam Surrey |

| Maintained by | British Columbia Ministry of Transportation |

| Followed by | Port Mann Bridge (second, 2012) |

| Characteristics | |

| Design | Tied-arch bridge |

| Total length | 2093 m |

| Longest span | 366 m |

| History | |

| Designer | CBA Engineering |

| Construction begin | 1957 |

| Construction end | 1963 |

| Construction cost | $25 million[1] |

| Opened | June 12, 1964 |

| Closed | November 17, 2012 |

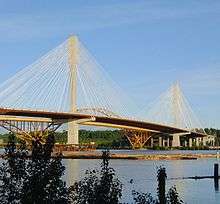

The Port Mann Bridge is a 10-lane cable-stayed bridge that opened to traffic in 2012. It is currently the second longest cable-stayed bridge in North America and was the widest bridge in the world until the opening of the new Bay Bridge in California.[3][4][5] The new bridge replaced a steel arch bridge that spanned the Fraser River, connecting Coquitlam to Surrey in British Columbia near Vancouver. The old bridge consisted of three spans with an orthotropic deck carrying five lanes of Trans-Canada Highway traffic, with approach spans of three steel plate girders and concrete deck. The total length of the previous Port Mann was 2,093 m (6,867 ft), including approach spans. The main span was 366 m (1,201 ft), plus the two 110 m (360 ft) spans on either side.[6] Volume on the old bridge was 127,000 trips per day.[7] Approximately 8 percent of the traffic on the Port Mann bridge was truck traffic.[8] The previous bridge was the longest arch bridge in Canada and third-longest in the world at the time of its inauguration.

History

The old Port Mann Bridge opened on June 12, 1964, originally carrying four lanes. It was named after the community of Port Mann, through which the south end of the bridge passed.[9] At the time of construction, it was the most expensive piece of highway in Canada. The first "civilian" to drive across the bridge was CKNW reporter Marke Raines. He was not authorized to cross, so he drove quickly.[10] In 2001 an eastbound HOV lane was added by moving the centre divider and by cantilevering the bridge deck outwards in conjunction with a seismic upgrade.[11]

Replacement

On January 31, 2006, the British Columbia Ministry of Transportation introduced the Gateway Program as a means to address growing congestion.[12] The project originally envisioned twinning the Port Mann Bridge by building a second bridge adjacent to it,[12] but the project was changed to building a 10-lane replacement bridge, planned to be the widest in the world, and demolishing the original bridge.

The Port Mann / Highway 1 project added another HOV lane and will provide cycling and pedestrian access. The multi-use pedestrian/bicycle path opened July 1, 2015. A bus service was reintroduced over the Port Mann Bridge for the first time in over 20 years. However, critics claimed that the new bridge only delayed the reintroduction of bus service on the bridge.[13][14] The new bus rapid transit service is now operated in the HOV lanes along Highway 1 from Langley to Burnaby.[15]

The estimated construction cost was $2.46 billion, including the cost of the Highway 1 upgrade, a total of 37 kilometres (23 mi). Of this, the bridge itself comprised roughly a third ($820 million).[1] The total cost, including operation and maintenance, was expected to be $3.3 billion. Now that the new bridge is completed, the existing bridge, which was more than 45 years old, has been taken down.[16]

The project was intended to be funded by using a public-private partnership, and Connect B.C. Development Group was chosen as the preferred developer. The Connect B.C. Group included the Macquarie Group, Transtoll Inc., Peter Kiewit Sons Co., and Flatiron Constructors.[17] Although a memorandum of understanding had been signed by the province, final terms could not be agreed upon. As a consequence, the province decided to fund the entire cost of replacement.[18]

The new bridge is 2.02 kilometres (1.26 mi) long, up to 65 metres (213 ft) wide, carries 10 lanes of traffic, and has a 42 metres (138 ft) clearance above the river's high water level (the same length and clearance as the old bridge). The towers are approximately 75 metres (246 ft) tall above deck level, with the total height approximately 163 metres (535 ft) from top of footing. The main span (between the towers) is 470 metres (1,540 ft) long, the second longest cable-stayed span in the western hemisphere. The main bridge (between the end of the cables) has a length of 850 metres (2,790 ft) with two towers and 288 cables. The new bridge was built to accommodate the future installation of light rapid transit.[19]

On September 18, 2012, the new Port Mann Bridge opened to eastbound traffic. At 65 metres (213 ft) wide, it was the world's widest long-span bridge, according to the Guinness World Records,[20] overtaking the world-famous Sydney Harbour Bridge, which, at 49 metres (161 ft), held the record since 1932.

Work to dismantle the old Port Mann Bridge began in December 2012. Crews removed sections of the bridge piece by piece in opposite order in which they were originally constructed, starting with the road deck, followed by the bridge approach's girders, and concluding with the steel arch. It was fully removed by October 2015.[21]

Opposition to twinning plan

A number of groups lobbied to improve public transit rather than build a new bridge. Burnaby city council, Vancouver city council, and directors of the GVRD (now Metro Vancouver) passed resolutions opposing the Port Mann / Highway 1 expansion.[22][23] Opponents of the expansion included local environmental groups, urban planners,[24] and Washington State's Sightline Institute.[25]

Opponents argued that increasing highway capacity would increase greenhouse gas emissions and only relieve congestion for a few years before increased traffic congested the area again,[26] and that expanding road capacity would encourage suburban sprawl. The Livable Region Coalition urged the Minister of Transportation, Kevin Falcon, to consider rapid transit lines and improved bus routes instead of building the new bridge.[27] The David Suzuki Foundation claimed the plan violated the goals of Metro Vancouver's Livable Region Strategic Plan.[28]

Issues

On February 10, 2012, during construction of the replacement bridge, an overhead gantry crane collapsed, causing a 90-tonne concrete box-girder segment to drop into the water below. While no one was injured, the accident delayed subsequent construction.[29] WorkSafeBC inspectors evaluated the safety practices on the construction site.

On December 19, 2012, cold weather caused ice to accumulate on the supporting cables, periodically dropping to the car deck below.[30] ICBC, the vehicle insurance entity in British Columbia, reported 60 separate claims of ice damage during the incident. In addition, one driver required an ambulance due to injuries. The RCMP closed the bridge between 1:30 p.m. and 6 p.m. while engineers investigated.[31]

Tolling

In order to recover construction and operating costs, the bridge is electronically tolled. The toll rates increased to $1.60 for motorcycle, $3.15 for cars, $6.30 for small trucks and $9.45 for large trucks on August 15, 2015.[32] Through increased prices and greater traffic, Transportation Investment Corporation (TI Corp), the public Crown corporation responsible for toll operations on the Port Mann Bridge, forecasts its revenue will grow by 85% between fiscal years 2014 and 2017.[33] These fees are assessed using radio-frequency identification (RFID) decals or licence plate photos. A B.C. licensed driver who owes more than $25 in tolls outstanding 90 days is penalized $20 and is unable to purchase vehicle insurance or renew drivers permits without payment of the debt.[34] Out-of-province drivers will also be contacted for payment by a US-based contractor.[35] A licence plate processing fee of $2.30 per trip will be added to the toll rate for unregistered users who do not pay their toll within seven days of their passage.[36] Monthly passes, which allow unlimited crossing on the bridge, are available for purchase.[37] Users may set up an account for online payment of tolls.[38] Users who opt for this method receive a decal with an embedded RFID to place on their vehicle's windshield or headlight and avoid paying a processing fee.[39] Tolls are expected to be removed by the year of 2050 or after collecting $3.3 billion.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Port Mann Bridge. |

References

- 1 2 3 Richard Gilbert (January 16, 2012), Engineer questions the decision to replace Port Mann bridge, Journal of Commerce, retrieved August 6, 2014

- ↑ "Facts & Trivia". Pmh1project.com. Retrieved December 7, 2012.

- ↑ http://www.guinnessworldrecords.com/world-records/6000/widest-bridge

- ↑ "Port Mann Improvement". BC Government. Retrieved December 29, 2012.

- ↑ "Port Mann Bridge sets Guinness record". CTV News. Retrieved December 29, 2012.

- ↑ "Port mann bridge". Buckland & Taylor Ltd. Retrieved February 10, 2007.

- ↑ "Gateway Program Definition Report" (PDF). Ministry of Transportation of British Columbia. January 31, 2005. Retrieved February 11, 2007.

- ↑ "Travel Characteristics of Traffic on the Highway 1 Corridor" (PDF). Greater Vancouver Transportation Authority. July 2, 2004. Retrieved January 1, 2008.

- ↑ "Surrey Archives". Retrieved December 27, 2012.

- ↑ Davis, Chuck. "1964 Chronology". The History of Metropolitan Vancouver. Retrieved February 10, 2007.

- ↑ http://www.kwhconstructors.com/brochures/KWH%20-%20Port%20Mann%20Bridge%20Widening%20-%20Construction%20-%202000.pdf

- 1 2 "Gateway Program Definition Report" (PDF). Ministry of Transportation of British Columbia. January 31, 2005. Retrieved February 11, 2007.

- ↑ Doherty, Eric. "Taken for a Ride: Technical and Media Manipulation in the Gateway Program's response to Transportation for a Sustainable Region: Transit or Freeway Expansion" (PDF). Livable Region Coalition. Retrieved September 1, 2011.

- ↑ Gillis, Damien. "Rapid Bus on Port Mann Bridge Now". Retrieved September 1, 2011.

- ↑ "Port Mann Bridge to have high speed bus service". CBC. October 5, 2007. Archived from the original on November 24, 2009. Retrieved February 18, 2009.

- ↑ "Single 10-lane bridge to replace Port Mann". CBC. February 4, 2009. Retrieved February 4, 2009.

- ↑ Agreement in Principle Reached for Port Mann Project - Ministry of Transportation and Infrastructure

- ↑ "Province to foot entire cost of new Port Mann Bridge". CBC. February 27, 2009. Archived from the original on February 28, 2009. Retrieved March 1, 2009.

- ↑ "Port Mann/Highway 1 Improvement Project" (PDF). Partnerships BC. March 2011. Retrieved July 4, 2016.

- ↑ "Port Mann Bridge sets Guinness record". CTV News. Retrieved September 20, 2012.

- ↑ "Old Port Mann Bridge has been finally dismantled". The Province. October 20, 2015. Retrieved July 4, 2016.

- ↑ "Burnaby Public Consultation on Provincial Gateway Program" (PDF). City of Burnaby. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 28, 2007. Retrieved February 11, 2007.

- ↑ "Standing Committee Minutes" (PDF). City of Vancouver. Retrieved February 11, 2007.

- ↑ Ward, Doug (June 20, 2006). "Planners oppose Gateway Program". The Vancouver Sun. Retrieved February 11, 2007.

- ↑ "B.C. gets top marks". North Shore Outlook. June 14, 2007. Retrieved June 15, 2007.

- ↑ "Gateway project will fail, planning prof warns". Steven Rees. October 2004. Retrieved June 15, 2007.

- ↑ "Questions about the B.C. Government's Port Mann and Highway 1 proposal for the Vancouver Region" (PDF). The Livable Region Coalition. October 2004. Retrieved February 11, 2007.

- ↑ "Proposed twinning of the Port Mann Bridge and Highway 1 expansion" (PDF). David Suzuki Foundation. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 18, 2007. Retrieved February 11, 2007.

- ↑ Evan Duggan (February 10, 2012). "Crane collapses on new Port Mann, drops 90 tonnes of concrete into water". Vancouver Sun. Retrieved February 12, 2012.

- ↑ IAN AUSTIN AND STEPHANIE IP (February 19, 2012). "Port Mann Bridge fix sought after 'ice bombs' shatter windshields". The Province. Retrieved February 19, 2012.

- ↑ "RAW: Port Mann closed after injuries". CBC BC News. February 19, 2012. Retrieved February 19, 2012.

- ↑ "Port Mann toll rates have changed". TReO. Retrieved August 26, 2015.

- ↑ "Failing to pay your toll". TReO (Transportation Investment Corporation). January 2, 2015. Retrieved January 2, 2015.

- ↑ "Failing to pay your toll" (PDF). TReO, Transportation Investment Corporation. January 2, 2015. Retrieved January 2, 2015.

- ↑ Kelly Sinoski (February 10, 2012). "Errant U.S. drivers to be tracked in B.C.". Vancouver Sun. Retrieved February 12, 2012.

- ↑ "TReO › Ways to save". Treo.ca. Retrieved December 21, 2012.

- ↑ "TReO › Ways to save". Treo.ca. Retrieved December 21, 2012.

- ↑ "TReO › Register Your Vehicle". Account.treo.ca. Retrieved December 21, 2012.

- ↑ "TReO › Vehicle Decals". Treo.ca. Retrieved December 21, 2012.