Qullqa

.jpg)

A qullqa (Quechua pronunciation: [ˈqʊʎˌqa] "deposit, storehouse";[1] (spelling variants: colca, collca, qolca, qollca) was a storage building found along roads and near the cities and political centers of the Inca Empire.[2] To an extent "unprecedented in the annals of world prehistory" the Incas stored food which could be distributed to the populace in times of need and also luxury items intended primarily for the nobility. The uncertainty of agriculture at the high altitudes which comprised most of the Inca Empire probably stimulated the construction of large numbers of qullqas.[3]

Background

The pre-Columbian Andean civilizations, of which the Inca Empire was the last, faced severe challenges in feeding the millions of people who were its subjects. The heartland of the empire and much of its land was at elevations between 3,000 metres (9,800 ft) and 4,000 metres (13,000 ft) and subject to frost, hail, and drought. Tropical crops could not be grown in the short growing seasons and a staple crop, maize, could not be grown above about 3,200 metres (10,500 ft) in elevation. The people at higher elevations grew potatoes, quinoa and a few other root and pseudocereal crops. Herding llamas and alpacas for meat, wool, and as beasts of burden was important.[4]

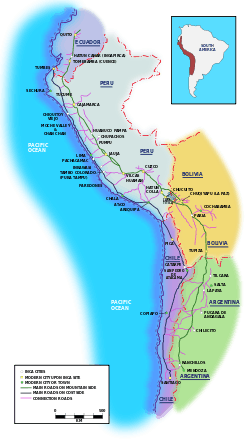

The response of the Incas to the challenges of their environment was a huge and well-organized system of qullqas to collect and store food and other items during good harvest years for distribution during poor harvest years. Large numbers of qullqas were constructed near every major governmental center and near state-owned farms, temples, and royal estates. Qullqas were built at every "tambo", the inns located a day's march, about 22 kilometres (14 mi), from each other along many of the 40,000 kilometres (25,000 mi) of royal highways.[5]

The qullqas also were used to supply Incan officials and armies on the move as they relied on the qullqas for food rather than foraging -- to the deprivation of the agricultural population -- which was the common means by which armies around the world supplied their needs until the modern era.

Size, Numbers and Location

_by_Guaman_Poma.jpg)

The average interior diameter of a small qullqa is 3.23 metres (10.6 ft); larger qullqas have a diameter of around 3.5–4.0 metres (11.5–13.1 ft). These smaller qullqa could have held 3.7 cubic metres (100 US bushels) of maize, and those larger qullqa could have held about 5.5 cubic metres (160 US bushels) maize.[6]

The largest number of qullqas, 2,573 of them, was built in the Mantaro Valley. Half of them were placed in the center of this grain-producing area, another half scattered among 48 compounds along the river.In total, the qullqas of the Mantaro Valley have a storage area of 170 thousand square meters, being the largest storage facility in pre-Columbian America.[7] These warehouse in Mantaro Valley supplied and equipped 35,000 auxiliaries.[8]

Each provincial center of the Empire had hundreds of qullqas built row after row on nearby hills.[7] Some of the qullqas built around Cusco also supplied local artisans and their products.[9] These storehouse, qullqa, are found in most of the best-preserved administrative center, along with usnu, inkawasi, aqllawasi, and temple of the sun.[10]

Other

Qullqa is an economic asset and strategic asset for Inka people. These storehouse kept tributes, and also could supply Inka armies because they are built along the roads.[2] It is also made to make sure when to start planting, predict rainfall, and the size of harvest.[11]

Qullqa and tampu served as storehouse showed the banking power of Inka empire.[12]

Qullqa is also the local name for the constellation Pleiades.[13] The Inca deity Qullqa, personified in the Pleiades, was the patron of warehousing and preserving seeds for the next season.[14] Of all the stellar pantheon worshipped by Incas, Qullqa was the "mother", the senior over all heavenly patrons of earthly things.[15]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Teofilo Laime Ajacopa, Diccionario Bilingüe Iskay simipi yuyayk'ancha, La Paz, 2007 (Quechua-Spanish dictionary)

- 1 2 Parsons, Timothy (2010). The Rule of Empires: Those Who Built Them, Those Who Endured Them, and Why They Always Fall. Oxford University Press. p. 137. ISBN 9780199746194.

- ↑ Moseley, Michael E. (2001), The Incas and their Ancestors, New York: Thames and Hudson, p. 77

- ↑ Moseley, p. 77

- ↑ McEwan, Gordon R. (2006), The Incas: New Perspectives," New York: W. W. Norton and Company, pp. 115, 119, 121

- ↑ D'Altroy, Terence N. (1992). Provincial power in the Inka empire. Smithsonian Institution Press. p. 175. ISBN 9781560981152.

- 1 2 D'Altroy, Terence N. (2003). The Incas. Wiley. p. 281. ISBN 9781405116763.

- ↑ Parsons, Timothy (2010). The Rule of Empires: Those Who Built Them, Those Who Endured Them, and Why They Always Fall. Oxford University Press. p. 139. ISBN 9780199746194.

- ↑ D'Altroy, Terence N. (2003). The Incas. Wiley. p. 124. ISBN 9781405116763.

- ↑ International Sociological Association (1981). "Comparative Urban Research". Volumes 8-9.

- ↑ Besom, Thomas (2013). Inka Human Sacrifice and Mountain Worship: Strategies for Empire Unification. University of New Mexico Press. p. 85. ISBN 978-0-8263-5308-5.

- ↑ Arnold, Denise Y., Christine A Hastorf (2008). HEADS OF STATE: ICONS, POWER, AND POLITICS IN THE ANCIENT AND MODERN ANDES. Left Coast Press. p. 138. ISBN 9781598741711.

- ↑ D'Altroy, Terence N. (2003). The Incas. Wiley. p. 28. ISBN 9781405116763.

- ↑ D'Altroy, Terence N. (2003). The Incas. Wiley. p. 146. ISBN 9781405116763.

- ↑ D'Altroy, Terence N. (2003). The Incas. Wiley. p. 150. ISBN 9781405116763.

References

- Terence N. D'Altroy (2003). The Incas. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 1-4051-1676-5.

- Teofilo Laime Ajacopa, Diccionario Bilingue Iskay Simipi Yuyayk'ancha, La Paz, 2007 (Quechua-Spanish Dictionary)

- Timothy Parsons (2010). The Rule of Empires: Those Who Built Them, Those Who Endured Them, and Why They Always Fall. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199746194

- Terence N. D'Altroy (1992). Provincial Power in The Inca Empire. Smithsonian Institution Press. ISBN 9781560981152.

- International Sociological Association (1981). Comparative Urban Research, Volumes 8-9.

- Denise Y. Arnold, Christine A. Hastorf (2008). Heads of State: Icons, Power, and Politics in The Ancient and Modern Andes. Lest Coast Press. ISBN 9781598741711.