Racism in the work of Charles Dickens

Although Charles Dickens is best known as a writer of coming-of-age novels about children and as a champion of the downtrodden poor,[1] he expresses (in common with many eminent writers of his time), both in his journalism and fiction, attitudes that can be interpreted as racist and xenophobic. While it cannot be said that he opposed fundamental freedoms of minorities in British society or supported legal segregation or employment discrimination, he defended the privileges of colonial Europeans and was dismissive of primitive cultures. The Oxford Dictionary of English Literature describes Dickens as nationalistic, often both stigmatising foreign European cultures and taking his attitude to "colonized people" to "genocidal extremes",[2] albeit based mainly on a vision of British virtue, rather than any concept of heredity. Ledger and Ferneaux do not believe he advocated any form of "scientific racism" regarding heredity – but still had the highest possible antipathy for the lifestyles of native peoples in British colonies, and believed that the sooner they were civilised, the better.[3]

Dickens scholar Grace Moore sees Dickens' racism as having abated in his later years, while cultural historian Patrick Brantlinger and journalist William Oddie see it as having intensified.[4] Moore contends that while Dickens later in life became far more sensitive to unethical aspects of British colonialism and came to plead mitigation of cruelties to natives, he never lost his distaste for those whose life style he regarded as primitive".

Controversies over Dickens' racism

Many scholars have noted the paradox between Dickens' support for various liberal causes and his racism, nationalist chauvinism and imperialist mentality. Biographer Peter Ackroyd in his 1990 biography of Dickens (the 2nd of four books on Dickens) duly notes Dickens' sympathy for the poor, opposition to child labour, campaigns for sanitation reform, and opposition to capital punishment. He also asserts that "In modern terminology Dickens was a "racist" of the most egregious kind, a fact that ought to give pause to those who persist in believing that he was necessarily the epitome of all that was decent and benign in the previous century."[5] Ackroyd also notes that Dickens did not believe that the North in the American Civil War was genuinely interested in the abolition of slavery, and he nearly publicly supported the South for that reason. Ackroyd twice notes that Dickens' major objection to missionaries was that they were more concerned with natives abroad than with the poor at home. For example, in his novel Bleak House Dickens mocks Mrs. Jellyby, who neglects her children for the natives of a fictional African country. The disjunction between Dickens' criticism of slavery and his crude caricatures of other races has also been noted by Patrick Brantlinger in his A Companion to the Victorian Novel. He cites Dickens' description of an Irish colony in America's Catskill mountains a mess of pigs, pots, and dunghills. Dickens views them as a "racially repellent" group.[6] Jane Smiley writing in the Penguin Lives bio of Dickens writes "we should not interpret him as the kind of left-liberal we know today-he was racist, imperialist, sometimes antisemitic, a believer in harsh prison conditions, and distrustful of trade unions.[7] An anthology of Dickens' essays from Household Words warns the reader in its introduction that in these essays "Women, the Irish, Chinese and Aborigines are described in biased, racist, stereotypical or otherwise less than flattering terms....We..encourage you to work towards a more positive understanding of the different groups that make up our community"[8] The Historical Encyclopedia of Anti-Semitism notes the paradox of Dickens both being a "champion of causes of the oppressed" who abhorred slavery and supported the European liberal revolutions of the 1840s, and his creation of the antisemitic caricature of the character of Fagin.[9]

Authors Sally Ledger and Holly Furneaux, in their book Dickens in Context examine this puzzle as to how one can square away Dickens' racialism with concern with the poor and the downcast. They argue this can be explained by saying that Dickens was a nativist and "cultural chauvinist" in the sense of being highly ethnocentric and ready to justify British imperialism, but not a racist in the sense of being a "biological determinist" as was the anthropologist Robert Knox. That is, Dickens did not regard the behaviour of races to be "fixed"; rather his appeal to "civilization" suggests not biological fixity but the possibility of alteration. However, "Dickens views of racial others, most fully developed in his short fiction, indicate that for him 'savages' functioned as a handy foil against which British national identity could emerge."[10]

The Oxford Encyclopedia of British Literature similarly notes that while Dickens praised middle-class values,

Dickens militancy about this catalog of virtues had nationalistic implications, since he praised these middle-class moral ideals as English national values. Conversely, he often stigmatized foreign cultures as lacking in these middle-class ideas, representing French, Italian, and American characters, in particular, as slothful and deceitful. His attitudes toward colonized peoples sometimes took these moral aspersions to genocidal extremes. In the wake of the so-called Indian Mutiny of 1857, he wrote..."I should do my utmost to exterminate the Race upon whom the stain of the late cruelties rested.." To be fair, Dickens did support the antislavery movement...and excoriated what he saw as English national vices[11]

William Oddie argues that Dickens's racism "grew progressively more illiberal over the course of his career" particularly after the Indian rebellion.[12] Grace Moore, on the other hand, argues that Dickens, a staunch abolitionist and opponent of imperialism, had views on racial matters that were a good deal more complex than previous critics have suggested in her work Dickens and Empire: [13] She suggests that overemphasising Dickens' racism obscures his continued commitment to the abolition of slavery.[14] Laurence Mazzeno has characterised Moore's approach as depicting Dickens' attitude to race as highly complex, "struggling to differentiate between ideas of race and class in his fiction...sometimes in step with his age, sometimes its fiercest critic."[15] Others have observed that Dickens also denied suffrage to blacks, writing in a letter "Free of course he must be; but the stupendous absurdity of making him a voter glares out of every roll of his eye".[16] Bernard Porter suggests that Dickens' race prejudice caused him to actually oppose imperialism rather than promote it citing the character of Mrs. Jellyby in Bleak House and the essay The Noble Savage as evidence.[17] However, Dickens did not join other liberals in condemning Jamaica's Governor Eyre's declaration of martial law after an attack on the capital's courthouse. In speaking on the controversy, Dickens' attacked "that platform sympathy with the black- or the native or the Devil.."[5]:971

In an essay on George Eliot, K.M. Newton notes:

Most of the major writers in the Victorian period can be seen as racist to a greater or lesser degree. According to Edward Said, even Marx and Mill are not immune: 'both of them seemed to have believed that such ideas as liberty, representative government, and individual happiness must not be applied to the Orient for reasons that today we would call racist'. In many of these writers antisemitism was the most obvious form of racism, and this continued beyond the Victorian period, as is evident in such figures as T. S. Eliot and Virginia Woolf.[18]

Fagin and Jews in Oliver Twist

One of the best known instances of racism is Dickens's portrait of Fagin in one of his most widely read early novels, Oliver Twist, first published in serial form between 1837 and 1839. This portayal has been seen by many as deeply antisemitic, though others such as Dickens's biographer G. K. Chesterton have argued against this notion. The novel refers to Fagin 257 times in the first 38 chapters as "the Jew", while the ethnicity or religion of the other characters is rarely mentioned. Paul Vallely wrote in The Independent that Dickens's Fagin in Oliver Twist —the Jew who runs a school in London for child pickpockets—is widely seen as one of the most grotesque Jews in English literature.[19] The character is thought to have been partly based on Ikey Solomon, a 19th-century Jewish criminal in London, who was interviewed by Dickens during the latter's time as a journalist.[20] Nadia Valdman, who writes about the portrayal of Jews in literature, argues that Fagin's representation was drawn from the image of the Jew as inherently evil, that the imagery associated him with the Devil, and with beasts.[21] The Historical Encyclopedia of Anti-Semitism argues that the image of Fagin is "drawn from stage melodrama and medieval images". Fagin is also seen as one who seduces young children into a life of crime, and as one who can "disorder representational boundaries".[9]

In 1854, the Jewish Chronicle asked why "Jews alone should be excluded from the 'sympathizing heart' of this great author and powerful friend of the oppressed." Eliza Davis, whose husband had purchased Dickens's home in 1860 when he had put it up for sale, wrote to Dickens in protest against his portrayal of Fagin, arguing that he had "encouraged a vile prejudice against the despised Hebrew", and that he had done a great wrong to the Jewish people.[22] Dickens had described her husband at the time of the sale as a "Jewish moneylender", though also someone he came to know as an honest gentleman.

Dickens protested that he was merely being factual about the realities of street crime, showing criminals in their "squalid misery", yet he took Mrs Davis's complaint seriously. He halted the printing of Oliver Twist, and changed the text for the parts of the book that had not been set, which is why Fagin is called "the Jew" 257 times in the first 38 chapters, but barely at all in the next 179 references to him. In his later novel Our Mutual Friend, he created the character of Riah (meaning "friend" in Hebrew), whose goodness, Vallely writes, is almost as complete as Fagin's evil. Riah says in the novel: "Men say, 'This is a bad Greek, but there are good Greeks. This is a bad Turk, but there are good Turks.' Not so with the Jews ... they take the worst of us as samples of the best ..." Davis sent Dickens a copy of the Hebrew bible in gratitude.[19] Dickens not only toned down Fagin's Jewishness in revised editions of Oliver Twist, but he removed Jewish elements from his depiction of Fagin in his public readings from the novel, omitting nasal voice mannerisms and body language he had included in earlier readings.[23]

Stage and screen adaptations

Joel Berkowitz reports that the earliest stage adaptations of Oliver Twist "followed by an almost unrelieved procession of Jewish stage distortions, and even helped to popularize a lisp for stage Jews that lasted until 1914"[24] It is widely believed that the most antisemitic adaptation of Oliver Twist is David Lean's film of 1948, with Alec Guinness as Fagin. Guinness was made-up to look like the illustrations from the novel's first edition. The film's release in the US was much delayed, due to Jewish protests, and was initially released with several of Fagin's scenes cut. This particular adaptation of the novel was banned in Israel.[25] Ironically, the film was also banned in Egypt for portraying Fagin too sympathetically.[26] When George Lucas's film Star Wars: Episode I – The Phantom Menace was released, he denied the claim made by some critics that the unscrupulous trader Watto (who has a hooked nose) was a Faginesque Jewish stereotype. However, animator Rob Coleman later admitted that he had viewed footage of Alec Guinness as Fagin in Oliver Twist to inspire his animators in creating Watto.[27]

The role of Fagin in Oliver Twist continues to be a challenge for actors who struggle with questions as to how to interpret the role in a post-Nazi era. Various Jewish writers, directors, and actors have searched for ways to "salvage" Fagin. In recent years, Jewish performers and writers have attempted to 'reclaim' Fagin as has been done with Shakespeare's Shylock in The Merchant of Venice. The composer of the 1960s musical Oliver!, Lionel Bart, was Jewish, and he wrote songs for the character with a Jewish rhythm and Jewish orchestration.[25] In spite of the musical's Jewish provenance, Jewish playwright Julia Pascal believes that performing the show today is still inappropriate, an example of a minority acting out on a stereotype to please a host society. Pascal says "U.S. Jews are not exposed to the constant low-level anti-Semitism that filters through British society". In contrast to Pascal, Yiddish expert David Schneider found the Dickens novel, wherein Fagin is simply "the Jew," a difficult read, but saw Fagin in the musical as "a complex character" who was not "the baddie."[25] Jewish stage producer Menachem Golan also created a less well-known Hebrew musical of Oliver Twist.[28] Some recent actors who have portrayed Fagin have tried to downplay Fagin's Jewishness, but actor Timothy Spall emphasised it while also making Fagin sympathetic. For Spall, Fagin is the first adult character in the story with actual warmth. He is a criminal, but is at least looking out for children more than the managers of Twist's workhouse. Spall says "The fact is, even if you were to turn Fagin into a Nazi portrayal of a Jew, there is something inherently sympathetic in Dickens's writing. I defy anyone to come away with anything other than warmth and pity for him."[29] Jewish actors who have portrayed Fagin on stage include Richard Kline,[30] Ron Moody in the Oscar-winning film of the musical Oliver!, and Richard Dreyfuss in a Disney live action TV production.

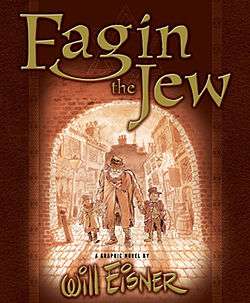

Will Eisner's 2003 graphic novel Fagin the Jew retells the story of Oliver Twist from Fagin's perspective, both humanising Fagin and making him authentically Jewish.[31]

Jewish filmmaker (and Holocaust survivor) Roman Polanski made a film adaptation of Oliver Twist in 2004. Concerning the portrait of Fagin in his film, Polanski said

"It's still a Jewish stereotype but without going overboard. He is not a Hassidic Jew. But his accent and looks are Jewish of the period. Ben said a very interesting thing. He said that with all his amoral approach to life, Fagin still provides a living for these kids. Of course, you can't condone pickpocketing. But what else could they do?"[32]

In the same interview, Polanski reluctantly notes that there are elements of Oliver Twist which echo his own childhood as an orphan in Nazi-occupied Poland. In reviewing the film, Norman Lebrecht argues that many previous adaptations of Oliver Twist have merely avoided the problem, but that Polanski found a solution "several degrees more original and convincing than previous fudges", noting that "Rachel Portman's attractive score studiously underplays the accompaniment of Jewish music to Jewish misery" and also that "Ben Kingsley endows the villain with tragic inevitability: a lonely old man, scrabbling for trinkets of security and a little human warmth", concluding that "It was certainly Dickens' final intention that 'the Jew' should be incidental in Oliver Twist and in his film Polanski has given the story a personal dimension that renders it irreproachably universal."[23]

African Americans in American Notes

Dickens's attitudes towards African Americans were also complex. In American Notes he fiercely opposed the inhumanity of slavery in the United States, and expressed a desire for African American emancipation. However, Grace Moore has noted how in the same work, he includes a comic episode with a black coach driver, presenting a grotesque description focused on the man's dark complexion and way of movement, which to Dickens amounts to an "insane imitation of an English coachman".[33] In 1868, in a letter alluding to the then-uneducated condition of the black population in America, Dickens railed against "the melancholy absurdity of giving these people votes", which "at any rate at present, would glare out of every roll of their eyes, chuckle in their mouths, and bump in their heads."[33]

Native Americans in The Noble Savage

_Going_To_and_Returning_From_Washington_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)

In his 1853 essay The Noble Savage, Dickens' attitude towards Native Americans is one of condescending pity, tempered (in the interpretation of Grace Moore)[34] by a counterbalancing concern with the arrogance of European colonialism. The term "noble savage" was in circulation since the 17th century, but Dickens regards it as an absurd oxymoron. He advocated that savages be civilised "off the face of the earth". In the The Noble Savage, Dickens ridicules the philosophical exaltation of an idyllic primitive man living in greater harmony with nature, an idea prevalent in what is called "romantic primitivism" (often erroneously attributed to Rousseau). Dickens rather touts the superiority of European culture and civilisation, while denouncing savages as murderous. Dickens essay was a response to painter George Catlin's exhibit of paintings of American natives (referred to by both Catlin and Dickens as "Indians") when it visited England. Dickens's expressed scorn for those unnamed individuals, who, like Catlin, he alleged, misguidedly exalted the so-called "noble savage". Dickens maintained the natives were dirty, cruel, and constantly fighting. Dickens's satire on Catlin and others like him who might find something to admire in the American natives or African Bushmen is a notable turning point in the history of the use of the phrase.[35] At the conclusion of the essay, note as he argues that although the virtues of the savage are mythical and his way of life inferior and doomed, he still "deserves to be treated no differently than if he were an Englishman of genius, such as Newton or Shakespeare."

Grace Moore in Dickens and Empire has argued that this essay is a transitional piece for Dickens. She sees Dickens' earlier writings as marked by a swing between conflicting opinions on race. The essay Noble Savage itself has an aggressive beginning, but concludes with a plea for kindness, while at the same time Dickens settles into a more stereotyped form of thinking, engaging in sweeping generalisations about peoples he had never encountered, in a way he avoided doing in earlier writings such as in his review of Narrative of the Niger Expedition. Finally, Moore notes that Dickens is in the same essay critical of many aspects of English society and suggests our own house should be put in order and criticises British arrogance in spreading her flawed view of civilisation across the globe.[13]:68–70

Professor Sian Griffiths has noted that Dickens' essay exhibits many of the same uncivil qualities he attributes to savages and writes:

"Dickens over-simplified defamation of Native American and African tribes seems largely prompted by what he saw as the over-simplified praise of the same people, evidenced in Caitlin's portraits...But by embracing the extreme opposing opinion, Dickens ultimately commits the same fault of failing to see the complexity of each individual human's character."[36]

Inuit in The Frozen Deep

Dickens in collaboration with Wilkie Collins, wrote The Frozen Deep, which premiered in 1856, an allegorical play about the missing Arctic Franklin expedition, and which attacked the character of the Inuit as covetous and cruel. The purpose of the play was to discredit explorer John Rae's report on the fate of the expedition, which concluded that the crew had turned to cannibalism, and was based largely on Inuit testimonies. Dickens initially had a positive assessment of the Inuit. The earlier Dickens, writing in "Our Phantom Ship on an Antediluvian Cruise", wrote of Eskimos as "gentle loving savages", but after The Times published a report by John Rae of the Eskimo discovery of the remains of the lost Franklin expedition with evidence that the crew resorted to cannibalism, Dickens reversed his stand. Dickens, in addition to Franklin's widow, refused to accept the report and accused the Eskimos of being liars, getting involved on Lady Franklin's side in an extended conflict with John Rae over the exact cause of the demise of the expedition. Lady Franklin wrote that the white Englishman could do no wrong exploring the wilderness and was considered able to "survive anywhere" and "to triumph over any adversity through faith, scientific objectivity, and superior spirit."[37] Dickens not only tried to discredit Rae and the Eskimos, but accused the Inuit of actively participating in Franklin's end. In "The Lost Arctic Voyagers", he wrote "It is impossible to form an estimate of the character of any race of savages from their deferential behaviour to the white man while he is strong. The mistake has been made again and again; and the moment the white man has appeared in the new aspect of being weaker than the savage, the savage has changed and sprung upon him." Explorer John Rae disputed with Dickens in two rebuttals (also published in Household Words). Rae defended the Inuit Eskimos as "a bright example to civilized people" and compared them favourably to the undisciplined crew of Franklin. Keal writes that Rae was no match for "Dickens the story teller", one of Lady Franklin's "powerful friends",[38] to the English he was a Scot who wasn't "pledged to the patriotic, empire-building aims of the military."[39] He was shunned by the English establishment as a result of his writing the report. Modern historians have vindicated Rae's belief that the Franklin crew resorted to cannibalism,[40] having already been decimated by scurvy and starvation; furthermore they were poorly prepared for wilderness survival contrary to Lady Hamilton's prejudices. in the play, the Rae character was turned into a suspicious, power-hungry nursemaid who predicted the expedition's doom in her effort to ruin the happiness of the delicate heroine.[37]

Reconciliation

During the filming of the 2008 Canadian documentary Passage, Gerald Dickens, Charles' great-great grandson was introduced to explain "why such a great champion of the underdog had sided with the establishment". Dickens' insult of the Inuit was a hurt they carried from generation to generation, Tagak Curley an Inuit statesman said to Gerald, "Your grandfather insulted my people. We have had to live with the pain of this for 150 years. This really harmed my people and is still harming them". Orkney historian Tom Muir is reported to have described Curley as "furious" and "properly upset". Gerald then apologised on behalf of the Dickens family, which Curley accepted on behalf of the Inuit people. Muir describes this as a "historic moment".[38]

Indians in The Perils of Certain English Prisoners

The Perils of Certain English Prisoners is an early work of fiction co-authored by Dickens and Wilkie Collins dealing allegorically with the Indian Rebellion of 1857. Patrick Brantlinger regards it as melodramatic and wildly inaccurate. It appeared in the 1857 Christmas number of Household Words.[41] In Perils Dickens describes the "native Sambo", a paradigm of the Indian mutineers,[42] as a "double-dyed traitor, and a most infernal villain" who takes part in a massacre of women and children, in an allusion to the Cawnpore Massacre.[43] Dickens was much incensed by the massacre in which over a hundred English prisoners, most of them women and children, were killed, and on 4 October 1857 Dickens wrote in a private letter to Baroness Burdett-Coutts: "I wish I were the Commander in Chief in India .... I should do my utmost to exterminate the Race upon whom the stain of the late cruelties rested ... proceeding, with all convenient dispatch and merciful swiftness of execution, to blot it out of mankind and raze it off the face of the earth."[44] Lillian Nayder has noted that Dickens collaborator, Wilkie Collins, lacked his hostility to the Indian people, nor faulted them for the mutiny to the degree that Dickens did. In Collins own work A Sermon for the Sepoys, he preaches to the Indian mutineers from an Indian sacred text, not a Christian one. Collins disassociates himself from Dickens privately expressed desire to exterminate the Indian race, but instead appeals to their capacity for moral goodness. Moreover, Collins' famous novel The Moonstone suggests that it is really the Indians who were mainly on the defensive during the mutiny, not the British, contrary to the prevalent impression given by the British press.[45]

Grace Moore observes that after a similar uprising in Jamaica, Dickens did not exhibit the same level of fury that he did towards the Indians in the Sepoy Rebellion. She attributes this to Dickens' greater awareness of the brutal actions of British soldiers toward natives in their colonies, and suggests that Dickens now regretted his former attitude. In taking this position, she directly argues against the views of Patrick Bratlinger and William Oldie who see racism as having gone unabated in the later writings of Dickens. However, Moore notes that while Dickens became increasingly aware of the unethical actions of British colonialists and how they provided a motivation for local rebellion, Dickens never lost his sense that there was nothing desirable about the life-style of foreign peoples, though[13]:Chapter 6

References

- ↑ For example published author Sue Wilkes describes him on her personal blog as "Champion of the poor" Dickens critique of the "stone-cold" heart of the upper classes is discussed in this review of the 2012 television presentation of Great Expectations

- ↑ Kastan, David Scott (2006). Oxford Encyclopedia of English Literature, vol 1. Oxford University Press. p. 157. ISBN 0-19-516921-2, 9780195169218

- ↑ Ledger, Sally; Holly Ferneaux (2011). Dickens in Context. Cambridge University Press. pp. 297–299. ISBN 0-521-88700-3, 9780521887007.

- ↑ Grace Moore, Dickens and Empire: Discourses Of Class, Race And Colonialism In The Works Of Charles Dickens (Nineteenth Century Series) (Ashgate: 2004).

- 1 2 Ackroyd, Peter (1990). Dickens. Harper Collins. p. 544. ISBN 0-06-016602-9. This is not the abridged edition published by Vintage as a tie-in to the BBC documentary

- ↑ Brantlinger, Patrick (2002). A Companion to the Victorian Novel. John Wiley & Sons. p. 91. ISBN 9780631220640.

- ↑ Smiley, Jane (2002). Penguin Lives: Charles Dickens. Penguin. p. 117. ISBN 9780670030774.

- ↑ Mendelawitz, Margaret (2011). Charles Dickens' Australia: Selected Essays from Household Words 1850–1859 ... Sydney University Press. p. vi. ISBN 9781920898687.

- 1 2 Levy, Richard (2005). Antisemitism: A Historical Encyclopedia of Prejudice and Persecution, Volume 1. ABC-CLIO. pp. 176–177 (Entry on "Dickens, Charles"). ISBN 9781851094394.

- ↑ Ledger, Sally; Holly Ferneaux (2011). Dickens in Context. Cambridge University Press. pp. 297–299. ISBN 9780521887007.

- ↑ Kastan, David Scott (2006). Oxford Encyclopedia of English Literature, vol 1. Oxford University Press. p. 157. ISBN 9780195169218.

- ↑ Dickens and Carlyle: the Question of Influence (London: Centenary) pp. 135–42, and “Dickens and the Indian Mutiny”, Dickensian 68 (January 1972), 3–15;

- 1 2 3 Dickens and Empire: Discourses Of Class, Race And Colonialism In The Works Of Charles Dickens (Nineteenth Century Series) (Ashgate: 2004).

- ↑ "Reappraising Dickens' Noble Savage" Dickensian 98.3 2002 p. 236-44

- ↑ Mazzeno, Laurence W. (2008). The Dickens industry: critical perspectives 1836–2005. Camden House. p. 247. ISBN 9781571133175.

- ↑ Colander, David; Robert E. Prasch; Falguni A. Sheth (2006). Race, Liberalism, and Economics. University of Michigan Press. p. 87. ISBN 9780472032242.

- ↑ Porter, Bernard (2007). Critics of Empire: British Radicals and the Imperial Challenge. I.B.Tauris. p. xxxii. ISBN 9781845115067.

- ↑ The Modern Language Review, July, 2008 "George Eliot and racism: how should one read 'The Modern Hep! Hep! Hep!'"? by K.M. Newton online at

- 1 2 Valley, Paul (7 October 2005). "Dickens' greatest villain: The faces of Fagin". The Independent. London: Independent Print Limited.

- ↑ Rutland, Suzanne D. The Jews in Australia. Cambridge University Press, 2005, p. 19. ISBN 978-0-521-61285-2; Newey, Vincent. The Scriptures of Charles Dickens.

- ↑ Valdman, Nadia. Antisemitism, A Historical Encyclopedia of Prejudice and Persecution. ISBN 1-85109-439-3

- ↑ Christopher Hitchens. "Charles Dickens’s Inner Child", Vanity Fair, February 2012

- 1 2 Norman Lebrecht (29 September 2005). "How Racist is Oliver Twist?". La Scena Musicale. Retrieved 14 March 2012.

- ↑ Joel Berkowitz. "Theatre entry at Jewish Virtual Library". Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved 14 March 2012.

- 1 2 3 Ben Quinn. "On the London Stage, New Depiction of Fagin Revives an Old Stereotype". All About Jewish Theatre. Retrieved 14 March 2012.

- ↑ Brooks, Xan (8 August 2000). "The ten best Alec Guinness movies". guardian.co.uk. London: Guardian News and Media Limited. Retrieved 31 March 2012.

- ↑ Silberman, Steve (May 1999). "G Force: George Lucas fires up the next generation of Star Warriors.". Wired (7.05). Retrieved 12 July 2009.

- ↑ e-bay listing of DVD

- ↑ John Nathan (18 December 2008). "This is how you play Fagin, Rowan". The Jewish Chronicle. Retrieved 11 March 2012.

- ↑ Anne Rackham. "Richard Kline gets back to his Jewish roots; but first, Fagin". Jewish News of Greater Phoenix. Retrieved 11 March 2012.

- ↑ TIME interview with author

- ↑ Sue Summers (1 October 2005). "Roman à clef". The Guardian, London. Retrieved 14 March 2012.

- 1 2 Grace Moore (28 November 2004). Dickens and Empire: Discourses of Class, Race and Colonialism in the Works of Charles Dickens. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-7546-3412-6. Retrieved 21 November 2010.

- ↑ Grace Moore, "Reappraising Dickens's 'Noble Savage'", The Dickensian 98:458 (2002): 236–243

- ↑ For an account of Dickens's article see Grace Moore, "Reappraising Dickens's 'Noble Savage'", The Dickensian 98:458 (2002): 236–243. Moore speculates that Dickens, although himself an abolitionist, was motivated by a wish to differentiate himself from what he believed was the feminine sentimentality and bad writing of Harriet Beecher Stowe, with whom he, as a reformist writer, was often associated.

- ↑ Sian Griffiths (11 January 2010). "Confronting a Prejudiced Dickens". Borrowed Horses- blog of published author and professor. Retrieved 13 March 2012.

- 1 2 Lady Jane Franklin; Erika Behrisch Elce (1 March 2009). As affecting the fate of my absent husband: selected letters of Lady Franklin concerning the search for the lost Franklin expedition, 1848–1860. McGill-Queen's Press – MQUP. pp. 25–. ISBN 978-0-7735-3479-7. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- 1 2 Keal, Graham (1 August 2008). "The incredible true story of forgotten Scots explorer John Rae". dailyrecord.co.uk. Scottish Daily Record and Sunday Mail Ltd. Retrieved 26 March 2012.

- ↑ Jen Hill (1 January 2009). White Horizon: The Arctic in the Nineteenth-Century British Imagination. SUNY Press. pp. 122–. ISBN 978-0-7914-7230-9. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- ↑ Robert Douglas-Fairhurst, "The Arctic heart of darkness: How heroic lies replaced hideous reality after the grim death of John Franklin", Times Literary Supplement, 11 November 2009.

- ↑ Patrick Brantlinger (1990). Rule of darkness: British literature and imperialism, 1830–1914. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-9767-4. Retrieved 13 February 2012.

- ↑ Stewart, Nicholas; Litvak, Dr. Leon. ""The Perils of Certain English Prisoners": Dickens' Defensive Fantasy of Imperial Stability". School of English, Queens University of Belfast. Retrieved 22 September 2009.

- ↑ Albert D. Pionke (1 June 2004). Plots of opportunity: representing conspiracy in Victorian England. Ohio State University Press. pp. 91–. ISBN 978-0-8142-0948-6. Retrieved 23 February 2012.

- ↑ Peter Scheckner (1989). An Anthology of Chartist poetry: poetry of the British working class, 1830s–1850s. Fairleigh Dickinson Univ Press. pp. 53–. ISBN 978-0-8386-3345-8. Retrieved 23 February 2012.

- ↑ Nayder, Laura (2002). Unequal partners: Charles Dickens, Wilkie Collins, and Victorian authorship. Cornell University Press. p. 167. ISBN 9780801439254.