Reasoned action approach

The reasoned-action approach (RAA) is an integrative framework for the prediction (and change) of human social behavior. The reasoned-action approach states that attitudes towards the behavior, perceived norms, and perceived behavioral control determine people’s intentions, while people’s intentions predict their behaviors.[1]

History

The reasoned-action approach is the latest version of the theoretical ideas of Martin Fishbein & Icek Ajzen, following the earlier theory of reasoned action [2] and the theory of planned behavior.[3] Those theoretical ideas have since 1975 resulted in over a thousand empirical studies in behavioral science journals. Martin (Marty) Fishbein died in November 2009.

Model

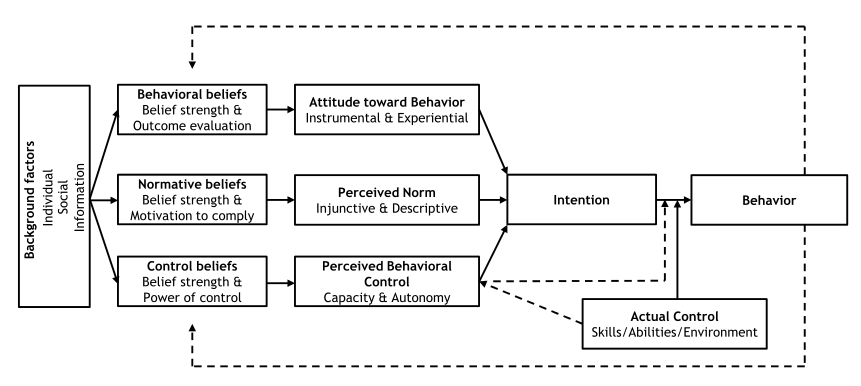

Behavior is determined by the intention and moderated by actual control. Intention is determined by attitude, perceived norm, and perceived behavioral control. Perceived behavioral control influences behavior directly and indirectly through intention. Actual control feeds back to perceived control. Performing the behavior feeds back to the beliefs underlying the three determinants of intention. All possible influences on behavior that are not in the model are treated as background variables and are supposed to be mediated by the determinants in the model.

Concepts

The reasoned-action approach uses a number of concepts, each of which is briefly defined here:

- Behaviors: observable events composed of four elements: the action performed, the target at which the action is directed, the context in which it is performed, and the time at which it is performed.

- Intentions: the person’s estimate of the likelihood or perceived probability of performing a given behavior.

- Perceived behavioral control: people’s perceptions of the degree to which they are capable of, or have control over, performing a given behavior.

- Capacity: the belief that one can, is able to, or is capable of, performing the behavior (comparable to Albert Bandura’s concept of self-efficacy); autonomy: perceived degree of control over performing the behavior.

- Actual control: relevant skills and abilities as well as barriers to and facilitators of behavioral performance.

- Attitude: a latent disposition or tendency to respond with some degree of favorableness or unfavorableness to a psychological object.

- Instrumental aspect: anticipated positive or negative consequences;

- Experiential aspect: perceived positive or negative experiences.

- Perceived norm: perceived social pressure to perform or not to perform a given behavior.

- Injunctive norm: perceptions concerning what should or ought to be done;

- Descriptive norms: perceptions that others are or are not performing the behavior in question.

Attitude, perceived norm, and perceived behavioral control are all based on beliefs: behavioral beliefs, normative beliefs, and control beliefs. Attitude is the result of the strength of behavioral beliefs reflecting positive and negative outcomes (and experiences) of the behavior, each multiplied by outcome evaluations in terms of good – bad. Perceived norm is the result of the strength of injunctive beliefs reflecting the expectations of various relevant others in the environment, each multiplied by the motivation to comply with these expectations, and of descriptive beliefs reflecting the behaviors of various relevant others, each multiplied by the degree of identification with these others. Perceived behavioral control is the result of the strength of control beliefs reflecting perceived skills, barriers and facilitators, each multiplied by the degree of power of control over these factors. These underlying beliefs have to be identified through a careful elicitation procedure, combining qualitative and quantitative research methods.

Measures

Concepts in the reasoned-action approach can be measured directly, and indirectly through the underlying beliefs.

Direct measures

These are a number of examples of the ways in which measurement items are constructed to measure the variables specified in the RAA.

- Behavior: (in terms of target, action, context, and time) i.e. "I (adolescent) always use condoms when having sex, at least during my teenage years", true – false.

- Intention: i.e. "I intend to [behavior]", likely – unlikely.

- Attitude: i.e. "My doing [behavior] would be" bad – good (instrumental), pleasant - unpleasant (experiential).

- Perceived norms: i.e. "Most people who are important to me think I should [behavior]", agree – disagree (injunctive); "most people like me do [behavior]", likely – unlikely (descriptive).

- Perceived behavioral control: i.e. "I am confident that I can do [behavior]", true – false (capacity); "my doing [behavior] is up to me", disagree – agree (autonomy).

Indirect measures

In their 2010 book, Fishbein & Ajzen[1] provide detailed examples of indirect measures in the Appendix, pp. 449–463.

Evaluation

The question of rationality

The reasoned-action approach has been criticized for being too rational. Fishbein & Ajzen[1] argue that to be a misunderstanding of the theory. There is nothing in their theory to suggest that people are rational; the theory only assumes that people have behavioral, normative and control beliefs which may be completely irrational but will determine behavior.

Reasoned versus automatic behavior

Another critical comment implies that most behavior is not intentional. Fishbein & Ajzen[1] argue that beliefs and intention can be activated automatically. They also suggest that alternative concepts, such as willingness,[4] are in fact measures of intentions. Implicit associations are often different from explicit attitude measures, but there is little evidence to suggest that they predict behavior more adequately.[5]

The question of sufficiency

A further criticism on the reasoned-action approach concerns the sufficiency assumption, which suggests that the theory captures all relevant determinants of intention. Ajzen[3] stated that the theory is open to the inclusion of additional predictors if it can be shown that they capture a significant proportion of the variance in intention or behavior after the theory’s current variables have been taken into account. Several researchers have indeed offered possible extensions, for example self-identity, next to the three current variables claiming these contribute significant additional explained variance in intention and behavior. In the reasoned-action approach, Fishbein and Ajzen[1] have indeed included new variables, but within the current three determinants (p. 282). They formulate strict criteria for a so-called 'fourth' variable and argue that none of the variables proposed fulfill these criteria.

Culture

With respect to social-cognitive theories in general, authors have criticized the 'Western' character of theories and argued that theories are not culture-free.[6] However, finding, in a specific cultural setting, specific beliefs that are not part of a general theory does not in itself invalidate the usefulness of the theory. Fishbein & Ajzen[1] have repeatedly stressed the importance of an open elicitation procedure to identify all relevant underlying beliefs. The theory of reasoned action and the theory of planned behavior have successfully been applied in many different cultural settings.

Applying to changing behavior

In the reasoned-action approach change is seen as a planned process in three phases: elicitation of the relevant beliefs, changing intentions by changing salient beliefs, and changing behavior by changing intentions and increasing skills or decreasing environmental barriers. The basic idea behind selecting any potential change method is that the salient beliefs are to be changed. Fishbein & Ajzen[1] recognize methods such as persuasive communication, use of arguments, framing, active participation, modeling, and group discussion,[7] but indicate that these methods will only have effect when salient behavioral, normative, or control beliefs are changed. Obviously, it is important that the salient beliefs are identified and measured correctly. Witte[8] suggests to first organize the results of the beliefs elicitation in a list of relevant categories (for example, behavioral beliefs, normative beliefs, self-efficacy beliefs, values) and then to decide which beliefs need to be changed, which need to be reinforced, and which need to be introduced.

Applications

The reasoned-action approach, mostly as the theory of planned behavior, is applied in many different settings and with many different behaviors, such as: health-related behaviors, sustainable behaviors, pro-social behaviors, traffic behaviors, organizational behaviors, political behaviors, and discriminatory behaviors.[1][7] A number of meta-analyses support the claims of the theory.[9][10][11][12][13][14]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (2010). Predicting and changing behavior: The Reasoned Action Approach. New York: Taylor & Francis.

- ↑ Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, attitude, intention and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Reading, MA: Addison Wesley.

- 1 2 Ajzen, I., 1991. The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50, 179–211.

- ↑ Gibbons, F.X., Gerrard, M., Cleveland, M.J., Wills, T.A. & Brody, G., 2004. Perceived discrimination and substance use in African American parents and their children: A panel study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 86(4), 517-529.

- ↑ Greenwald, A.G., Poehlman, T.A., Uhlmann, E.L. & Banaji, M.R., 2009. Understanding and using the Implicit Association Test: III. Meta-analysis of predictive validity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97(1), 17 -41.

- ↑ Pasick, R. J., Burke, N. J., Barker, J. C., Joseph, G., Bird, J. A., Otero-Sabogal, R., et al., 2009. Behavioral theory in a diverse society: like a compass on Mars. Health Education and Behavior, 36, 11S–35S.

- 1 2 Bartholomew, L. K., Parcel, G. S., Kok, G., Gottlieb, N. H., & Fernández, M.E., 2011. Planning health promotion programs; an Intervention Mapping approach, 3rd Ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- ↑ Witte, K. (1995). Fishing for success: Using the persuasive health message framework to generate effective campaign messages. In E. Maibach & R. L. Parrott (Eds.), Melissa Meazzo,Designing health messages: Approaches from communication theory and public health practice (pp. 145–166). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- ↑ Godin, G. & Kok, G., 1996. The Theory of Planned Behavior: A review of its applications to health-related problems. American Journal of Health Promotion, 11, 87-98.

- ↑ Albarracín, D., Johnson, B.T.; Fishbein, M., Muellerleile, P.A., 2001. Theories of reasoned action and planned behavior as models of condom use: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 127(1), 142-161.

- ↑ Armitage, C.J. & Conner, M., 2001. Efficacy of the Theory of Planned Behavior: A meta-analytic review. British Journal of Social Psychology, 40(4), 471–499.

- ↑ Webb, Th., Joseph, J., Yardley, L. & Michie, S., 2010. Using the Internet to promote health behavior change: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of theoretical basis, use of behavior change techniques, and mode of delivery on efficacy. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 10 (Feb 17); 12(1):e4.

- ↑ McEachan , R.R.C., Conner, M. , Taylor, N.J. & Lawton, R.J., 2011. Prospective prediction of health-related behaviors with the Theory of Planned Behavior: a meta-analysis. Health Psychology Review, 5(2), 97-144.

- ↑ van der Linden, S. (2011). "Charitable Intent: A Moral or Social Construct? A Revised Theory of Planned Behavior Model". Current Psychology. 30 (4): 355–374. doi:10.1007/s12144-011-9122-1.

External links

- http://www.annenbergpublicpolicycenter.org/events/martin-fishbein-memorial-seminar-series/

- The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 2012 640