Rivaroxaban

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Xarelto |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Micromedex Detailed Consumer Information |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of administration | oral |

| ATC code | B01AX06 (WHO) |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 80% to 100%; Cmax = 2 – 4 hours (10 mg oral)[1] |

| Metabolism | CYP3A4 , CYP2J2 and CYP-independent mechanisms[1] |

| Biological half-life | 5 – 9 hours in healthy subjects aged 20 to 45[1][2] |

| Excretion | 2/3 metabolized in liver and 1/3 eliminated unchanged[1] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| Synonyms | Xarelto, BAY 59-7939 |

| CAS Number |

366789-02-8 |

| PubChem (CID) | 6433119 |

| IUPHAR/BPS | 6388 |

| DrugBank |

DB06228 |

| ChemSpider |

8051086 |

| UNII |

9NDF7JZ4M3 |

| ChEMBL |

CHEMBL198362 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.210.589 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C19H18ClN3O5S |

| Molar mass | 435.882 g/mol |

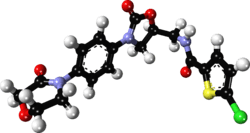

| 3D model (Jmol) | Interactive image |

| |

| |

| | |

Rivaroxaban (BAY 59-7939) is an oral anticoagulant invented and manufactured by Bayer;[3][4] in a number of countries it is marketed as Xarelto.[1] In the United States, it is marketed by Janssen Pharmaceutica.[5] It is the first available orally active direct factor Xa inhibitor. Rivaroxaban is well absorbed from the gut and maximum inhibition of factor Xa occurs four hours after a dose. The effects last approximately 8–12 hours, but factor Xa activity does not return to normal within 24 hours so once-daily dosing is possible.

Medical uses

In those with non-valvular atrial fibrillation it appears to be as effective as warfarin in preventing nonhemorrhagic strokes and embolic events.[6] Rivaroxaban is associated with lower rates of serious and fatal bleeding events than warfarin though rivaroxaban is associated with higher rates of bleeding in the gastrointestinal tract.[7]

In September 2008, Health Canada granted marketing authorization for rivaroxaban for the prevention of venous thromboembolism (VTE) in people who have undergone elective total hip replacement or total knee replacement surgery.[8]

In September 2008, the European Commission granted marketing authorization of rivaroxaban for the prevention of venous thromboembolism in adults undergoing elective hip and knee replacement surgery.[9]

On July 1, 2011, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved rivaroxaban for prophylaxis of deep vein thrombosis (DVT), which may lead to pulmonary embolism (PE), in adults undergoing hip and knee replacement surgery.[5]

On November 4, 2011, the U.S. FDA approved rivaroxaban for stroke prevention in people with non-valvular atrial fibrillation.[10]

In July 2012 the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence recommended rivaroxaban for the prevention and treatment of venous thromboembolism.[11]

Adverse effects

As with any anticoagulant the most serious adverse effect is bleeding, including severe internal bleeding.[12][13][14] There is currently no antidote for rivaroxaban (unlike warfarin, the action of which can be reversed with vitamin K or prothrombin complex concentrate), meaning that serious bleeding may be difficult to manage. A possible antidote (andexanet alfa) is being investigated.[15] Post-marketing assessments showed signs of liver toxicity associated with rivaroxaban, although studies are required to adequately quantify the risk.[16][17]

Xarelto has a boxed warning to make clear that people using the drug should not discontinue it before talking with their health care professional. Discontinuing the drug can increase the risk of stroke.[18]

In 2015, rivaroxaban accounted for the highest number of reported cases of serious injury among regularly monitored drugs to the FDA's Adverse Events Reporting System (AERS).[19]

Mechanism of action

Rivaroxaban is an oxazolidinone derivative optimized for inhibiting both free Factor Xa and Factor Xa bound in the prothrombinase complex.[3] It is a highly selective direct Factor Xa inhibitor with oral bioavailability and rapid onset of action. Inhibition of Factor Xa interrupts the intrinsic and extrinsic pathway of the blood coagulation cascade, inhibiting both thrombin formation and development of thrombi. Rivaroxaban does not inhibit thrombin (activated Factor II), and no effects on platelets have been demonstrated.[1]

Rivaroxaban has predictable pharmacokinetics across a wide spectrum of patients (age, gender, weight, race) and has a flat dose response across an eightfold dose range (5–40 mg).[20] Clinical trial data have shown that it allows predictable anticoagulation with no need for dose adjustments and routine coagulation monitoring.[1] However, these trials have excluded people with significant liver disease and end-stage kidney disease; therefore, the safety of rivaroxaban in these populations is unknown.

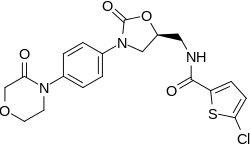

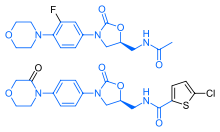

Chemistry

Rivaroxaban bears a striking structural similarity to the antibiotic linezolid: both drugs share the same oxazolidinone-derived core structure. Accordingly, rivaroxaban was studied for any possible antimicrobial effects and for the possibility of mitochondrial toxicity, which is a known complication of long-term linezolid use. Studies found that neither rivaroxaban nor its metabolites have any antibiotic effect against Gram-positive bacteria. As for mitochondrial toxicity, in vitro studies found the risk to be low.[21]

Related drugs

A number of anticoagulants inhibit the activity of Factor Xa. Unfractionated heparin (UFH), low molecular weight heparin (LMWH), and fondaparinux inhibit the activity of factor Xa indirectly by binding to circulating antithrombin (AT III). These agents must be injected. Warfarin, phenprocoumon, and acenocoumarol are orally active vitamin K antagonists (VKA) which decrease the liver's production of a number of coagulation factors, including Factor X. In recent years, a new series of oral, direct acting inhibitors of Factor Xa have entered clinical development. These include rivaroxaban, apixaban, betrixaban, LY517717, darexaban (YM150), and edoxaban (DU-176b).[22]

Research

In October 2014, Portola Pharmaceuticals announced the completion of Phase I and Phase II clinical trials for andexanet alfa as an antidote for Factor Xa inhibitors with few adverse effects, as well as the start of Phase III trials. The compound has yet to be approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.[23]

Researchers at the Duke Clinical Research Institute have been accused of withholding clinical data used to evaluate the blood thinner drug Xarelto.[24] Xarelto was tested at Duke in a 2011 clinical trial known as the ROCKET AF trial.[25] The original 2011 clinical trial was published in the New England Journal of Medicine[26] and headed by Manesh Patel, M.D. and Robert Califf, M.D. (current Commissioner of the FDA[27])[26] found Xarelto to be more effective than the standard prescription of warfarin in reducing the likelihood of ischemic strokes in patients with atrial fibrillation, or abnormal heart rhythms.[26] The validity of the study, however, was called into question in 2014 when pharmaceutical sponsors Bayer and Johnson & Johnson revealed that the INRatio blood monitoring devices used to evaluate the effectiveness of the drugs studied in the ROCKET AF trial were not functioning properly.[24][25][28]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Xarelto: Summary of Product Characteristics". Bayer Schering Pharma AG. 2008. Retrieved 2009-02-11.

- ↑ Abdulsattar, Y; Bhambri, R; Nogid, A (May 2009). "Rivaroxaban (xarelto) for the prevention of thromboembolic disease: an inside look at the oral direct factor xa inhibitor.". P & T : a peer-reviewed journal for formulary management. 34 (5): 238–44. PMID 19561868.

- 1 2 Roehrig S, Straub A, Pohlmann J, et al. (September 2005). "Discovery of the novel antithrombotic agent 5-chloro-N-({(5S)-2-oxo-3- [4-(3-oxomorpholin-4-yl)phenyl]-1,3-oxazolidin-5-yl}methyl)thiophene- 2-carboxamide (BAY 59-7939): an oral, direct factor Xa inhibitor". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 48 (19): 5900–8. doi:10.1021/jm050101d. PMID 16161994.

- ↑ Perzborn, Elisabeth; Roehrig, Susanne; Straub, Alexander; Kubitza, Dagmar; Misselwitz, Frank (17 December 2010). "The discovery and development of rivaroxaban, an oral, direct factor Xa inhibitor". Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 10 (1): 61–75. doi:10.1038/nrd3185.

- 1 2 "FDA Approves XARELTO® (rivaroxaban tablets) to Help Prevent Deep Vein Thrombosis in Patients Undergoing Knee or Hip Replacement Surgery" (Press release). Janssen Pharmaceutica. 2011-07-01. Retrieved 2011-07-01.

- ↑ Gómez-Outes, A; Terleira-Fernández, AI; Calvo-Rojas, G; Suárez-Gea, ML; Vargas-Castrillón, E (2013). "Dabigatran, Rivaroxaban, or Apixaban versus Warfarin in Patients with Nonvalvular Atrial Fibrillation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Subgroups.". Thrombosis. 2013: 640723. doi:10.1155/2013/640723. PMC 3885278

. PMID 24455237.

. PMID 24455237. - ↑ Brown DG, Wilkerson EC, Love WE (March 2015). "A review of traditional and novel oral anticoagulant and antiplatelet therapy for dermatologists and dermatologic surgeons". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 72 (3): 524–34. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.10.027. PMID 25486915.

- ↑ "Bayer's Xarelto Approved in Canada" (Press release). Bayer. 2008-09-16. Retrieved 2010-01-31.

- ↑ "Bayer's Novel Anticoagulant Xarelto now also Approved in the EU" (Press release). Bayer. 2008-02-10. Retrieved 2010-01-31.

- ↑ "FDA approves Xarelto to prevent stroke in people with common type of abnormal heart rhythm". U.S. Food and Drug Association. 4 November 2011. Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- ↑ http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/TA261 NICE guidance TA261

- ↑ "Medication Guide--Xarelto" (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 1 September 2014.

- ↑ "Xarelto Side Effects". WebMD. Retrieved 1 September 2014.

- ↑ "Xarelto Side Effects Center". RxList. Retrieved 1 September 2014.

- ↑ Mo Y, Yam FK (Feb 2015). "Recent advances in the development of specific antidotes for target-specific oral anticoagulants". Pharmacotherapy. 35 (2): 198–207. doi:10.1002/phar.1532. PMID 25644580.

- ↑ Raschi, Emanuel; Poluzzi, Elisabetta; Koci, Ariola; Salvo, Francesco; Pariente, Antoine; Biselli, Maurizio; Moretti, Ugo; Moore, Nicholas; De Ponti, Fabrizio (2015-08-01). "Liver injury with novel oral anticoagulants: assessing post-marketing reports in the US Food and Drug Administration adverse event reporting system". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 80 (2): 285–293. doi:10.1111/bcp.12611. ISSN 1365-2125. PMC 4541976

. PMID 25689417.

. PMID 25689417. - ↑ Russmann, Stefan; Niedrig, David F.; Budmiger, Mathias; Schmidt, Caroline; Stieger, Bruno; Hürlimann, Sandra; Kullak-Ublick, Gerd A. (2014-08-01). "Rivaroxaban postmarketing risk of liver injury". Journal of Hepatology. 61 (2): 293–300. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2014.03.026. ISSN 1600-0641. PMID 24681117.

- ↑ "XARELTO (rivaroxaban) label" (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Association.

- ↑ Schroeder, C. "ISMP Ranks Xarelto Most Dangerous Drug in the United States". DrugNews. DrugNews. Retrieved 10 August 2016.

- ↑ Eriksson BI, Borris LC, Dahl OE, et al. (November 2006). "A once-daily, oral, direct Factor Xa inhibitor, rivaroxaban (BAY 59-7939), for thromboprophylaxis after total hip replacement". Circulation. 114 (22): 2374–81. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.642074. PMID 17116766.

- ↑ European Medicines Agency (2008). "CHP Assessment Report for Xarelto (EMEA/543519/2008)" (PDF). Retrieved 2009-06-11.

- ↑ Turpie AG (January 2008). "New oral anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation". European Heart Journal. 29 (2): 155–65. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehm575. PMID 18096568.

- ↑ Schroeder, C. "Possible Antidote Could Help Blood Thinner Patients In Bleeding Emergencies". DrugNews. Retrieved 20 August 2015.

- 1 2 Thomas, Katie. "Document Claims Drug Makers Deceived a Top Medical Journal". The New York Times. The New York Times. Retrieved 3 May 2016.

- 1 2 Patel, Vir. "Duke clinical trial under scrutiny in drug case". The Chronicle. Duke Student Publishing Company.

- 1 2 3 "Rivaroxaban versus Warfarin in Nonvalvular Atrial Fibrillation". The New England Journal of Medicine. Massachusetts Medical Society.

- ↑ "Meet Robert M. Califf, M.D., Commissioner of Food and Drugs". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 3 May 2016.

- ↑ "Point-of-Care Warfarin Monitoring in the ROCKET AF Trial". The New England Journal of Medicine. Massachusetts Medical Society.

External links

- Rivaroxaban bound to proteins in the PDB

- Xarelto – Prescribing Information (European Union)

- Xarelto – Prescribing Information (United States)