Robert E. Lee

| General Robert E. Lee | |

|---|---|

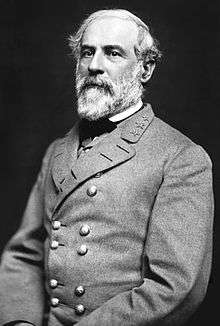

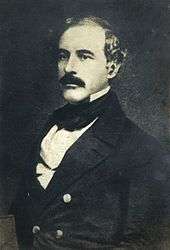

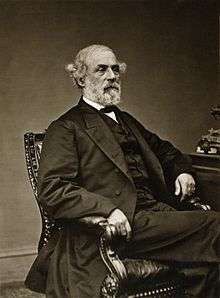

Julian Vannerson's photograph of Robert E. Lee in March 1864 | |

| Birth name | Robert Edward Lee |

| Nickname(s) | Bobby Lee (never to his face), Uncle Robert, Marse Robert, Granny Lee, the King of Spades, the Old Man, the Marble Man |

| Born |

January 19, 1807 Stratford Hall, Virginia, U.S. |

| Died |

October 12, 1870 (aged 63) Lexington, Virginia, U.S. |

| Buried at | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/branch | |

| Years of service |

|

| Rank | |

| Commands held | |

| Battles/wars | |

| Other work | President of Washington and Lee University |

| Signature |

|

Robert Edward Lee (January 19, 1807 – October 12, 1870) was an American general known for commanding the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia in the American Civil War from 1862 until his surrender in 1865. The son of Revolutionary War officer Henry "Light Horse Harry" Lee III, Lee was a top graduate of the United States Military Academy and an exceptional officer and military engineer in the United States Army for 32 years. During this time, he served throughout the United States, distinguished himself during the Mexican–American War, and served as Superintendent of the United States Military Academy.

When Virginia declared its secession from the Union in April 1861, Lee chose to follow his home state, despite his personal desire for the country to remain intact and despite an offer of a senior Union command.[1] During the first year of the Civil War, Lee served as a senior military adviser to President Jefferson Davis. Once he took command of the main field army in 1862 he soon emerged as a shrewd tactician and battlefield commander, winning most of his battles, all against far superior Union armies.[2][3] Lee's strategic foresight was more questionable, and both of his major offensives into Union territory ended in defeat.[4][5][6] Lee's aggressive tactics, which resulted in high casualties at a time when the Confederacy had a shortage of manpower, have come under criticism in recent years.[7] Lee surrendered his entire army to Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865. By this time, Lee had assumed supreme command of the remaining Southern armies; other Confederate forces swiftly capitulated after his surrender. Lee rejected the proposal of a sustained insurgency against the Union and called for reconciliation between the two sides.

After the war, as President of what is now Washington and Lee University, Lee supported President Andrew Johnson's program of Reconstruction and intersectional friendship, while opposing the Radical Republican proposals to give freed slaves the vote and take the vote away from ex-Confederates. He urged them to rethink their position between the North and the South, and the reintegration of former Confederates into the nation's political life. Lee became the great Southern hero of the War, a postwar icon of the "Lost Cause of the Confederacy" to some. But his popularity grew even in the North, especially after his death in 1870.[8] Barracks at West Point built in 1962 are named after him.

Early life and career

Robert Edward Lee was born at Stratford Hall Plantation in Westmoreland County, Virginia, to Major General Henry Lee III (Light Horse Harry) (1756–1818), Governor of Virginia, and his second wife, Anne Hill Carter (1773–1829). His birth date has traditionally been recorded as January 19, 1807, but according to the historian Elizabeth Brown Pryor, "Lee's writings indicate he may have been born the previous year."[9]

the family seat, Lee's birthplace

"Lee Corner" properties

One of Lee's great grandparents, Henry Lee I, was a prominent Virginian colonist of English descent.[10] Lee's family is one of Virginia's first families, originally arriving in Virginia from England in the early 1600s with the arrival of Richard Lee I, Esq., "the Immigrant" (1618–64), from the county of Shropshire.[11] His mother grew up at Shirley Plantation, one of the most elegant homes in Virginia.[12] Lee's father, a tobacco planter, suffered severe financial reverses from failed investments.[13]

Little is known of Lee as a child; he rarely spoke of his boyhood as an adult.[14] Nothing is known of his relationship with his father who, after leaving his family, mentioned Robert only once in a letter. When given the opportunity to visit his father's Georgia grave, he remained there only briefly yet, while as president of Washington College, he defended his father in a biographical sketch while editing Light Horse Harry's memoirs.[15] In 1809, Harry Lee was put in debtors prison; soon after his release the following year, Harry and Anne Lee and their five children moved to a small house on Cameron Street in Alexandria, Virginia, both because there were then high quality local schools there, and because several members of her extended family lived nearby.[16] In 1811, the family, including the newly born sixth child, Mildred, moved to a house on Oronoco Street, still close to the center of town and with the houses of a number of Lee relatives close by.[17] In 1812, Harry Lee was badly injured in a political riot in Baltimore and traveled to the West Indies. He would never return, dying when his son Robert was eleven years old.[18] Left to raise six children alone in straitened circumstances, Anne Lee and her family often paid extended visits to relatives and family friends.[19] Robert Lee attended school at Eastern View, a school for young gentlemen, in Fauquier County, and then at the Alexandria Academy, free for local boys, where he showed an aptitude for mathematics. Although brought up to be a practicing Christian, he was not confirmed in the Episcopal Church until age 46.[20]

Anne Lee's family was often supported by a relative, William Henry Fitzhugh, who owned the Oronoco Street house and allowed the Lees to stay at his home in Fairfax County, Ravensworth. When Robert was 17 in 1824, Fitzhugh wrote to the Secretary of War, John C. Calhoun, urging that Robert be given an appointment to the United States Military Academy at West Point. Fitzhugh wrote little of Robert's academic prowess, dwelling much on the prominence of his family, and erroneously stated the boy was 18. Instead of mailing the letter, Fitzhugh had young Robert deliver it.[21] In March 1824, Robert Lee received his appointment to West Point, but due to the large number of cadets admitted, Lee would have to wait a year to begin his studies there.[22]

Lee entered West Point in the summer of 1825. At the time, the focus of the curriculum was engineering; the head of the Army Corps of Engineers supervised the school and the superintendent was an engineering officer. Cadets were not permitted leave until they had finished two years of study, and were rarely allowed off the Academy grounds. Lee graduated second in his class behind Charles Mason,[23] who resigned from the Army a year after graduation, and Lee did not incur any demerits during his four-year course of study, a distinction shared by five of his 45 classmates. In June 1829, Lee was commissioned a brevet second lieutenant in the Corps of Engineers.[24] After graduation, while awaiting assignment, he returned to Virginia to find his mother on her deathbed; she died at Ravensworth on July 26, 1829.[25]

| Ancestors of Robert E. Lee | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Military engineer career

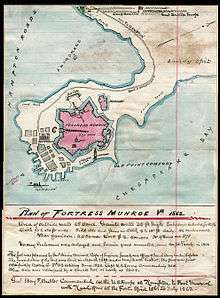

On August 11, 1829, Brigadier General Charles Gratiot ordered Lee to Cockspur Island, Georgia. The plan was to build a fort on the marshy island which would command the outlet of the Savannah River. Lee was involved in the early stages of construction as the island was being drained and built up.[26] In 1831, it became apparent that the existing plan to build what became known as Fort Pulaski would have to be revamped, and Lee was transferred to Fort Monroe at the tip of the Virginia Peninsula (today in Hampton, Virginia).[27]

While home in the summer of 1829, Lee had apparently courted Mary Custis whom he had known as a child. Lee obtained permission to write to her before leaving for Georgia, though Mary Custis warned Lee to be "discreet" in his writing, as her mother read her letters, especially from men.[28] Custis refused Lee the first time he asked to marry her; her father did not believe the son of the disgraced Light Horse Harry Lee was a suitable man for his daughter.[29] She accepted him with her father's consent in September 1830, while he was on summer leave,[30] and the two were wed on June 30, 1831.[31]

Lee's duties at Fort Monroe were varied, typical for a junior officer, and ranged from budgeting to designing buildings.[32] Although Mary Lee accompanied her husband to Hampton Roads, she spent about a third of her time at Arlington, though the couple's first son, Custis Lee was born at Fort Monroe. Although the two were by all accounts devoted to each other, they were different in character: Robert Lee was tidy and punctual, qualities his wife lacked. Mary Lee also had trouble transitioning from being a rich man's daughter to having to manage a household with only one or two slaves.[33] Beginning in 1832, Robert Lee had a close but platonic relationship with Harriett Talcott, wife of his fellow officer Andrew Talcott.[34]

Lee's early duty station

Lee's hand-drawn sketch

Life at Fort Monroe was marked by conflicts between artillery and engineering officers. Eventually the War Department transferred all engineering officers away from Fort Monroe, except Lee, who was ordered to take up residence on the artificial island of Rip Raps across the river from Fort Monroe, where Fort Wool would eventually rise, and continue work to improve the island. Lee duly moved there, then discharged all workers and informed the War Department he could not maintain laborers without the facilities of the fort.[35]

In 1834, Lee was transferred to Washington as General Gratiot's assistant.[36] Lee had hoped to rent a house in Washington for his family, but was not able to find one; the family lived at Arlington, though Lieutenant Lee rented a room at a Washington boarding house for when the roads were impassable.[37] In mid-1835, Lee was assigned to assist Andrew Talcott in surveying the southern border of Michigan.[38] While on that expedition, he responded to a letter from an ill Mary Lee, which had requested he come to Arlington, "But why do you urge my immediate return, & tempt one in the strongest manner[?] ... I rather require to be strengthened & encouraged to the full performance of what I am called on to execute."[27] Lee completed the assignment and returned to his post in Washington, finding his wife ill at Ravensworth. Mary Lee, who had recently given birth to their second child, remained bedridden for several months. In October 1836, Lee was promoted to first lieutenant.[39]

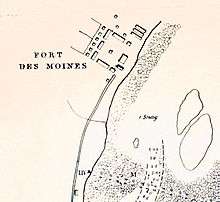

Lee served as an assistant in the chief engineer's office in Washington, D.C. from 1834 to 1837, but spent the summer of 1835 helping to lay out the state line between Ohio and Michigan. As a first lieutenant of engineers in 1837, he supervised the engineering work for St. Louis harbor and for the upper Mississippi and Missouri rivers. Among his projects was the mapping of the Des Moines Rapids on the Mississippi above Keokuk, Iowa, where the Mississippi's mean depth of 2.4 feet (0.7 m) was the upper limit of steamboat traffic on the river. His work there earned him a promotion to captain. Around 1842, Captain Robert E. Lee arrived as Fort Hamilton's post engineer.[40]

Marriage and family

While Lee was stationed at Fort Monroe, he married Mary Anna Randolph Custis (1808–73), great-granddaughter of Martha Washington by her first husband Daniel Parke Custis, and step-great-granddaughter of George Washington, the first president of the United States. Mary was the only surviving child of George Washington Parke Custis, George Washington's stepgrandson, and Mary Lee Fitzhugh Custis, daughter of William Fitzhugh[41] and Ann Bolling Randolph. Robert and Mary married on June 30, 1831, at Arlington House, her parents' house just across from Washington, D.C. The 3rd U.S. Artillery served as honor guard at the marriage. They eventually had seven children, three boys and four girls:

- George Washington Custis Lee (Custis, "Boo"); 1832–1913; served as Major General in the Confederate Army and aide-de-camp to President Jefferson Davis, captured during the Battle of Sailor's Creek; unmarried

- Mary Custis Lee (Mary, "Daughter"); 1835–1918; unmarried

- William Henry Fitzhugh Lee ("Rooney"); 1837–91; served as Major General in the Confederate Army (cavalry); married twice; surviving children by second marriage

- Anne Carter Lee (Annie); June 18, 1839 – October 20, 1862; died of typhoid fever, unmarried

- Eleanor Agnes Lee (Agnes); 1841 – October 15, 1873; died of tuberculosis, unmarried

- Robert Edward Lee, Jr. (Rob); 1843–1914; served as Captain in the Confederate Army (Rockbridge Artillery); married twice; surviving children by second marriage

- Mildred Childe Lee (Milly, "Precious Life"); 1846–1905; unmarried

All the children survived him except for Annie, who died in 1862. They are all buried with their parents in the crypt of the Lee Chapel at Washington and Lee University in Lexington, Virginia.

Lee was a great-great-great grandson of William Randolph and a great-great grandson of Richard Bland.[42] He was also related to Helen Keller through Helen's mother, Kate, and was a distant relative of Admiral Willis Augustus Lee.

On May 1, 1864, General Lee was at the baptism of General A.P. Hill's daughter, Lucy Lee Hill, to serve as her godfather. This is referenced in the painting Tender is the Heart by Mort Künstler.[43]

Mexican–American War

Lee distinguished himself in the Mexican–American War (1846–48). He was one of Winfield Scott's chief aides in the march from Veracruz to Mexico City. He was instrumental in several American victories through his personal reconnaissance as a staff officer; he found routes of attack that the Mexicans had not defended because they thought the terrain was impassable.

He was promoted to brevet major after the Battle of Cerro Gordo on April 18, 1847.[44] He also fought at Contreras, Churubusco, and Chapultepec and was wounded at the last. By the end of the war, he had received additional brevet promotions to Lieutenant Colonel and Colonel, but his permanent rank was still Captain of Engineers and he would remain a Captain until his transfer to the cavalry in 1855.

For the first time, Robert E. Lee and Ulysses S. Grant met and worked with each other during the Mexican–American War. Both Lee and Grant participated in Scott's march from the coastal town of Vera Cruz to Mexico City. Grant gained wartime experience as a quartermaster, Lee as an engineer who positioned troops and artillery. Both did their share of actual fighting. At Vera Cruz, Lee earned a commendation for "greatly distinguished" service. Grant was among the leaders at the bloody assault at Molino del Rey, and both soldiers were among the forces that entered Mexico City. Close observations of their commanders constituted a learning process for both Lee and Grant.[45] The Mexican–American War concluded on February 2, 1848.

After the Mexican War, Lee spent three years at Fort Carroll in Baltimore harbor. During this time, his service was interrupted by other duties, among them surveying and updating maps in Florida. Cuban revolutionary Narciso López intended to forcibly liberate Cuba from Spanish rule. In 1849, searching for a leader for his filibuster expedition, he approached Jefferson Davis, then a United States senator. Davis declined and suggested Lee, who also declined. Both decided it was inconsistent with their duties.[46][47]

Early 1850s: West Point and Texas

The 1850s were a difficult time for Lee, with his long absences from home, the increasing disability of his wife, troubles in taking over the management of a large slave plantation, and his often morbid concern with his personal failures.[48]

In 1852, Lee was appointed Superintendent of the Military Academy at West Point;[49] he was reluctant to enter what he called a "snake pit", but the War Department insisted and he obeyed. His wife occasionally came to visit. During his three years at West Point, Brevet Colonel Robert E. Lee improved the buildings and courses and spent much time with the cadets. Lee's oldest son, George Washington Custis Lee, attended West Point during his tenure. Custis Lee graduated in 1854, first in his class.[50]

Lee was enormously relieved to receive a long-awaited promotion as second-in-command of the Second Cavalry regiment in Texas in 1855. It meant leaving the Engineering Corps and its sequence of staff jobs for the combat command he truly wanted. He served under Colonel Albert Sidney Johnston at Camp Cooper, Texas; their mission was to protect settlers from attacks by the Apache and the Comanche.

Late 1850s: Arlington plantation and the Custis slaves

Mary Custis' inheritance in 1857

the Lees worshiped here

In 1857, his father-in-law George Washington Parke Custis died, creating a serious crisis when Lee took on the burden of executing the will. Custis's will encompassed vast landholdings and hundreds of slaves balanced against massive debts, and required Custis's former slaves "to be emancipated by my executors in such manner as to my executors may seem most expedient and proper, the said emancipation to be accomplished in not exceeding five years from the time of my decease."[51] The estate was in disarray, and the plantations had been poorly managed and were losing money.

Lee tried to hire an overseer to handle the plantation in his absence, writing to his cousin, "I wish to get an energetic honest farmer, who while he will be considerate & kind to the negroes, will be firm & make them do their duty."[52] But Lee failed to find a man for the job, and had to take a two-year leave of absence from the army in order to run the plantation himself. He found the experience frustrating, since many of the slaves had been given to understand that they were to be made free as soon as Custis died, and protested angrily at the delay.[53] In May 1858, Lee wrote to his son Rooney, "I have had some trouble with some of the people. Reuben, Parks & Edward, in the beginning of the previous week, rebelled against my authority—refused to obey my orders, & said they were as free as I was, etc., etc.—I succeeded in capturing them & lodging them in jail. They resisted till overpowered & called upon the other people to rescue them."[52] Less than two months after they were sent to the Alexandria jail, Lee decided to remove these three men and three female house slaves from Arlington, and sent them under lock and key to the slave-trader William Overton Winston in Richmond, who was instructed to keep them in jail until he could find "good & responsible" slaveholders to work them until the end of the five-year period.[52]

The Norris case

In 1859, three of the Arlington slaves—Wesley Norris, his sister Mary, and a cousin of theirs—fled for the North, but were captured a few miles from the Pennsylvania border and forced to return to Arlington. On June 24, 1859, the anti-slavery newspaper New York Daily Tribune published two anonymous letters (dated June 19, 1859[54] and June 21, 1859[55]), each claiming to have heard that Lee had the Norrises whipped, and each going so far as to claim that the overseer refused to whip the woman but that Lee took the whip and flogged her personally. Lee privately wrote to his son Custis that "The N. Y. Tribune has attacked me for my treatment of your grandfather's slaves, but I shall not reply. He has left me an unpleasant legacy."[56]

Wesley Norris himself spoke out about the incident after the war, in an 1866 interview printed in an abolitionist newspaper, the National Anti-Slavery Standard. Norris stated that after they had been captured, and forced to return to Arlington, Lee told them that "he would teach us a lesson we would not soon forget." According to Norris, Lee then had the three of them firmly tied to posts by the overseer, and ordered them whipped with fifty lashes for the men and twenty for Mary Norris. Norris claimed that Lee encouraged the whipping, and that when the overseer refused to do it, called in the county constable to do it instead. Unlike the anonymous letter writers, he does not state that Lee himself personally whipped any of the slaves. According to Norris, Lee "frequently enjoined [Constable] Williams to 'lay it on well,' an injunction which he did not fail to heed; not satisfied with simply lacerating our naked flesh, Gen. Lee then ordered the overseer to thoroughly wash our backs with brine, which was done."[53][57]

The Norris men were then sent by Lee's agent to work on the railroads in Virginia and Alabama. According to the interview, Norris was sent to Richmond in January 1863 "from which place I finally made my escape through the rebel lines to freedom." But Federal authorities reported that Norris came within their lines on September 5, 1863, and that he "left Richmond...with a pass from General Custis Lee."[58][59] Lee freed the Custis slaves, including Wesley Norris, after the end of the five-year period in the winter of 1862, filing the deed of manumission on December 29, 1862.[60][61]

Biographers of Lee have differed over the credibility of the account of the punishment as described in the letters in the Tribune and in Norris's personal account. They broadly agree that Lee had a group of escaped slaves recaptured, and that after recapturing them he hired them out off of the Arlington plantation as a punishment; but they disagree over the likelihood that Lee flogged them, and over the charge that he personally whipped Mary Norris. In 1934, Douglas S. Freeman described them as "Lee's first experience with the extravagance of irresponsible antislavery agitators" and asserted that "There is no evidence, direct or indirect, that Lee ever had them or any other Negroes flogged. The usage at Arlington and elsewhere in Virginia among people of Lee's station forbade such a thing."[62]

In 2000, Michael Fellman, in The Making of Robert E. Lee, found the claims that Lee had personally whipped Mary Norris "extremely unlikely," but found it not at all unlikely that Lee had ordered the runaways whipped: "corporal punishment (for which Lee substituted the euphemism 'firmness') was (believed to be) an intrinsic and necessary part of slave discipline. Although it was supposed to be applied only in a calm and rational manner, overtly physical domination of slaves, unchecked by law, was always brutal and potentially savage."[63]

In 2003, Bernice-Marie Yates's The Perfect Gentleman, cited Freeman's denial and followed his account in holding that, because of Lee's family connections to George Washington, he "was a prime target for abolitionists who lacked all the facts of the situation."[64]

Lee biographer Elizabeth Brown Pryor concluded in 2008 that "the facts are verifiable," based on "the consistency of the five extant descriptions of the episode (the only element that is not repeatedly corroborated is the allegation that Lee gave the beatings himself), as well as the existence of an account book that indicates the constable received compensation from Lee on the date that this event occurred."[65][66]

In 2014, Michael Korda wrote that "Although these letters are dismissed by most of Lee's biographers as exaggerated, or simply as unfounded abolitionist propaganda, it is hard to ignore them. [...] It seems incongruously out of character for Lee to have whipped a slave woman himself, particularly one stripped to the waist, and that charge may have been a flourish added by the two correspondents; interestingly enough, it was not repeated by Wesley Norris when his account of the incident was published in 1866. [...] [A]lthough it seems unlikely that he would have done any of the whipping himself, he may not have flinched from observing it to make sure his orders were carried out exactly."[67]

Lee's views on slavery

Since the end of the Civil War, it has often been suggested Lee was in some sense opposed to slavery. In the period following the war, Lee became a central figure in the Lost Cause interpretation of the war. The argument that Lee had always somehow opposed slavery helped maintain his stature as a symbol of Southern honor and national reconciliation. Freeman's analysis places Lee's attitude toward slavery and abolition in a historical context:

This [opinion] was the prevailing view among most religious people of Lee's class in the border states. They believed that slavery existed because God willed it and they thought it would end when God so ruled. The time and the means were not theirs to decide, conscious though they were of the ill-effects of Negro slavery on both races. Lee shared these convictions of his neighbors without having come in contact with the worst evils of African bondage. He spent no considerable time in any state south of Virginia from the day he left Fort Pulaski in 1831 until he went to Texas in 1856. All his reflective years had been passed in the North or in the border states. He had never been among the blacks on a cotton or rice plantation. At Arlington, the servants had been notoriously indolent, their master's master. Lee, in short, was only acquainted with slavery at its best, and he judged it accordingly. At the same time, he was under no illusion regarding the aims of the Abolitionists or the effect of their agitation.[68]

A key source cited by defenders and critics is Lee's 1856 letter to his wife:[68]

... In this enlightened age, there are few I believe, but what will acknowledge, that slavery as an institution, is a moral & political evil in any Country. It is useless to expatiate on its disadvantages. I think it however a greater evil to the white man than to the black race, & while my feelings are strongly enlisted in behalf of the latter, my sympathies are more strong for the former. The blacks are immeasurably better off here than in Africa, morally, socially & physically. The painful discipline they are undergoing, is necessary for their instruction as a race, & I hope will prepare & lead them to better things. How long their subjugation may be necessary is known & ordered by a wise Merciful Providence.— Robert E. Lee, to Mary Anna Lee, December 27, 1856

The evidence cited in favor of the claim that Lee opposed slavery included his direct statements and his actions before and during the war, including Lee's support of the work by his wife and her mother to liberate slaves and fund their move to Liberia,[69] the success of his wife and daughter in setting up an illegal school for slaves on the Arlington plantation,[70] the freeing of Custis' slaves in 1862, and, as the Confederacy's position in the war became desperate, his petitioning slaveholders in 1864–65 to allow slaves to volunteer for the Army with manumission offered as a reward for outstanding service.[71][72]

However, despite his stated opinions, Lee's troops under his command were allowed to actively raid settlements during major operations like the 1863 invasion of Pennsylvania to freely capture Free Blacks for enslavement.[73][74][75][76][77][78]

In December 1864 Lee was shown a letter by Louisiana Senator Edward Sparrow, written by General St. John R. Liddell, which noted Lee would be hard-pressed in the interior of Virginia by spring, and the need to consider Patrick Cleburne's plan to emancipate the slaves and put all men in the army who were willing to join. Lee was said to have agreed on all points and desired to get black soldiers, saying "he could make soldiers out of any human being that had arms and legs."[79]

Harpers Ferry and Texas, 1859–61

Both Harpers Ferry and the secession of Texas were monumental events leading up to the Civil War. Robert E. Lee was at both events. Lee initially remained loyal to the Union after Texas seceded.

Harpers Ferry

John Brown led a band of 21 abolitionists who seized the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, in October 1859, hoping to incite a slave rebellion. President James Buchanan gave Lee command of detachments of militia, soldiers, and United States Marines, to suppress the uprising and arrest its leaders.[80] By the time Lee arrived that night, the militia on the site had surrounded Brown and his hostages. At dawn, Brown refused the demand for surrender. Lee attacked, and Brown and his followers were captured after three minutes of fighting. Lee's summary report of the episode shows Lee believed it "was the attempt of a fanatic or madman". Lee said Brown achieved "temporary success" by creating panic and confusion and by "magnifying" the number of participants involved in the raid.[81]

Texas

In 1860, Lt. Col. Robert E. Lee relieved Major Heintzelman at Fort Brown, and the Mexican authorities offered to restrain "their citizens from making predatory descents upon the territory and people of Texas...this was the last active operation of the Cortina War". Rip Ford, a Texas Ranger at the time, described Lee as, "dignified without hauteur, grand without pride...he evinced an imperturbable self-possession, and a complete control of his passions...possessing the capacity to accomplish great ends and the gift of controlling and leading men."[82]

When Texas seceded from the Union in February 1861, General David E. Twiggs surrendered all the American forces (about 4,000 men, including Lee, and commander of the Department of Texas) to the Texans. Twiggs immediately resigned from the U. S. Army and was made a Confederate general. Lee went back to Washington and was appointed Colonel of the First Regiment of Cavalry in March 1861. Lee's colonelcy was signed by the new President, Abraham Lincoln. Three weeks after his promotion, Colonel Lee was offered a senior command (with the rank of Major General) in the expanding Army to fight the Southern States that had left the Union. Fort Mason, Texas was Lee's last command with the United States Army.[83]

Civil War

Lee privately opposed the Confederacy in letters in early 1861, denouncing secession as "nothing but revolution" and an unconstitutional betrayal of the efforts of the Founding Fathers. Writing to his eldest son in January, Lee stated:

The South, in my opinion, has been aggrieved by the acts of the North, as you say. I feel the aggression, and am willing to take every proper step for redress. It is the principle I contend for, not individual or private benefit. As an American citizen, I take great pride in my country, her prosperity and institutions, and would defend any State if her rights were invaded. But I can anticipate no greater calamity for the country than a dissolution of the Union. It would be an accumulation of all the evils we complain of, and I am willing to sacrifice everything but honor for its preservation. I hope, therefore, that all constitutional means will be exhausted before there is a resort to force. Secession is nothing but revolution. The framers of our Constitution never exhausted so much labor, wisdom, and forbearance in its formation, and surrounded it with so many guards and securities, if it was intended to be broken by every member of the Confederacy at will. It was intended for "perpetual union," so expressed in the preamble, and for the establishment of a government, not a compact, which can only be dissolved by revolution, or the consent of all the people in convention assembled.[84]

Despite his opposition to secession in principle, Lee's objection on the basis of constitutionality was ultimately outweighed by a sense of personal honor, reservations about the legitimacy of a strife-ridden "Union that can only be maintained by swords and bayonets," and duty to defend his native Virginia if attacked.[85] Lee held no illusions about the prospect of civil war and was one of few to correctly foresee the protracted and devastating nature of the conflict.[86]

The commanding general of the Union Army, Winfield Scott, told Lincoln he wanted Lee for a top command. Lee accepted a promotion to colonel on March 28.[87] He had earlier been asked by one of his lieutenants if he intended to fight for the Confederacy or the Union, to which Lee replied, "I shall never bear arms against the Union, but it may be necessary for me to carry a musket in the defense of my native state, Virginia, in which case I shall not prove recreant to my duty."[88] Meanwhile, Lee ignored an offer of command from the Confederate States of America. After Lincoln's call for troops to put down the rebellion, it was obvious that Virginia would quickly secede. Lee on April 18 was offered by presidential advisor Francis P. Blair a role as major general to command the defense of Washington. He replied:

- Mr. Blair, I look upon secession as anarchy. If I owned the four millions of slaves in the South I would sacrifice them all to the Union; but how can I draw my sword upon Virginia, my native state?[89]

Lee resigned from the U.S. Army on April 20 and took up command of the Virginia state forces on April 23.[23] While historians have usually called his decision inevitable ("the answer he was born to make", wrote one; another called it a "no-brainer") given the ties to family and state, an 1871 letter from his eldest daughter, Mary Custis Lee, to a biographer described Lee as "worn and harassed" yet calm as he deliberated alone in his office.[90] Aside from Mary, a secessionist, his family was overwhelmingly pro-Union. While Lee's immediate family followed him to the Confederacy, others, such as cousins and fellow officers Samuel Phillips and John Fitzgerald Lee, remained loyal to the Union, as did 40 percent of Virginian officers.[91]

Early role

At the outbreak of war, Lee was appointed to command all of Virginia's forces, but upon the formation of the Confederate States Army, he was named one of its first five full generals. Lee did not wear the insignia of a Confederate general, but only the three stars of a Confederate colonel, equivalent to his last U.S. Army rank.[92] He did not intend to wear a general's insignia until the Civil War had been won and he could be promoted, in peacetime, to general in the Confederate Army.

Lee's first field assignment was commanding Confederate forces in western Virginia, where he was defeated at the Battle of Cheat Mountain and was widely blamed for Confederate setbacks.[93] He was then sent to organize the coastal defenses along the Carolina and Georgia seaboard, appointed commander, "Department of South Carolina, Georgia and Florida" on November 5, 1861. Between then and the fall of Fort Pulaski, April 11, 1862, he put in place a defense of Savannah that proved successful in blocking Federal advance on Savannah. Confederate fort and naval gunnery dictated night time movement and construction by the besiegers. Federal preparations required four months. In those four months, Lee developed a defense in depth. Behind Fort Pulaski on the Savannah River, Fort Jackson was improved, and two additional batteries covered river approaches.[94] In the face of the Union superiority in naval, artillery and infantry deployment, Lee was able to block any Federal advance on Savannah, and at the same time, well-trained Georgia troops were released in time to meet McClellan's Peninsula Campaign. The City of Savannah would not fall until Sherman's approach from the interior at the end of 1864.

At first, the press spoke to the disappointment of losing Fort Pulaski. Surprised by the effectiveness of large caliber Parrott Rifles in their first deployment, it was widely speculated that only betrayal could have brought overnight surrender to a Third System Fort. Lee was said to have failed to get effective support in the Savannah River from the three sidewheeler gunboats of the Georgia Navy. Although again blamed by the press for Confederate reverses, he was appointed military adviser to Confederate President Jefferson Davis, the former U.S. Secretary of War. While in Richmond, Lee was ridiculed as the 'King of Spades' for his excessive digging of trenches around the capitol. These trenches would later play a pivotal role in battles near the end of the war.[95]

Commander, Army of Northern Virginia

Following the wounding of Gen. Joseph E. Johnston at the Battle of Seven Pines, on June 1, 1862, Lee assumed command of the Army of Northern Virginia, his first opportunity to lead an army in the field. Early in the war, his men called him "Granny Lee" because of his allegedly timid style of command.[96] Confederate newspaper editorials of the day objected to his appointment due to concerns that Lee would not be aggressive and would wait for the Union army to come to him. He oversaw substantial strengthening of Richmond's defenses during the first three weeks of June. In the spring of 1862, as part of the Peninsula Campaign, the Union Army of the Potomac under General George B. McClellan advanced upon Richmond from Fort Monroe, eventually reaching the eastern edges of the Confederate capital along the Chickahominy River. Lee then launched a series of attacks, the Seven Days Battles, against McClellan's forces. Lee's assaults resulted in heavy Confederate casualties. They were marred by clumsy tactical performances by his division commanders, but his aggressive actions unnerved McClellan, who retreated to a point on the James River and abandoned the Peninsula Campaign. These successes led to a rapid turnaround of Confederate public opinion, and the newspaper editorials changed their attitude toward Lee's aggressiveness. After the Seven Days Battles until the end of the war his men called him simply "Marse Robert", a term of respect and affection.

This Unionist setback—followed by a drop in Northern morale—impelled Lincoln to adopt a new policy of relentless, committed warfare.[97][98] Three weeks after the Seven Days Battles, Lincoln informed his cabinet that he intended to issue an executive order to free slaves as a military necessity.[99] After McClellan's retreat, Lee defeated another Union army at the Second Battle of Bull Run. Within 90 days of taking command, Lee had run McClellan off the Peninsula, defeated John Pope at Second Manassas, and the battle lines had moved from 6 miles (9.7 km) outside Richmond, to 20 miles (32 km) outside Washington. Lee then invaded Maryland, hoping to replenish his supplies and possibly influence the Northern elections to fall in favor of ending the war. McClellan's men found a lost Confederate despatch, Special Order 191, that revealed Lee's plans. McClellan always exaggerated Lee's numerical strength, but now he knew the Confederate army was divided and could be destroyed by an all-out attack at Antietam. McClellan, however, was too slow in moving, not realizing Lee had been informed by a spy that McClellan had the plans. Lee urgently recalled Stonewall Jackson, concentrating his forces west of Antietam Creek, near Sharpsburg, Maryland. In the bloodiest day of the war, with both sides suffering enormous losses, Lee withstood the Union assaults. He withdrew his battered army back to Virginia while President Abraham Lincoln used the Confederate reversal as an opportunity to announce the Emancipation Proclamation[100] which put the Confederacy on the diplomatic and moral defensive, and would ultimately devastate the Confederacy's slave-based economy.[101]

Disappointed by McClellan's failure to destroy Lee's army, Lincoln named Ambrose Burnside as commander of the Army of the Potomac. Burnside ordered an attack across the Rappahannock River at Fredericksburg. Delays in building bridges across the river allowed Lee's army ample time to organize strong defenses, and the frontal assault on December 13, 1862, was a disaster for the Union. There were 12,600 Union casualties to 5,000 Confederate; one of the most one-sided battles in the Civil War.[102] Lee reportedly stated after the Confederate victory, "It is well that war is so terrible--we should grow too fond of it".[102] At Fredericksburg, according to historian Michael Fellman, Lee had completely entered into the "spirit of war, where destructiveness took on its own beauty."[102] After the bitter Union defeat at Fredericksburg, President Lincoln named Joseph Hooker commander of the Army of the Potomac. Hooker's advance to attack Lee in May 1863, near Chancellorsville, Virginia, was defeated by Lee and Stonewall Jackson's daring plan to divide the army and attack Hooker's flank. It was a victory over a larger force, but it also came with high casualties. It was particularly costly in one respect: Lee's finest corps commander, Stonewall Jackson, was accidentally fired upon by his own troops. Weakened by his wounds, he died some days later, most likely of pneumonia.[103]

Battle of Gettysburg

The critical decisions came in May–June 1863, after Lee's smashing victory at the Battle of Chancellorsville. The western front was crumbling, as multiple uncoordinated Confederate armies were unable to handle General Ulysses S. Grant's campaign against Vicksburg. The top military advisers wanted to save Vicksburg, but Lee persuaded Davis to overrule them and authorize yet another invasion of the North. The immediate goal was to acquire urgently needed supplies from the rich farming districts of Pennsylvania; a long-term goal was to stimulate peace activity in the North by demonstrating the power of the South to invade. Lee's decision proved a significant strategic blunder and cost the Confederacy control of its western regions, and nearly cost Lee his own army as Union forces cut him off from the South. Lee had to fight his way out at Gettysburg.[104]

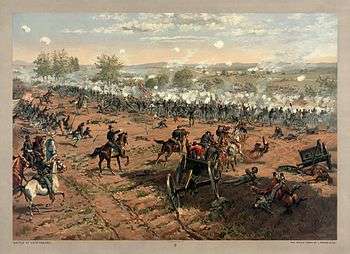

In the summer of 1863, Lee invaded the North again, marching through western Maryland and into south central Pennsylvania. He encountered Union forces under George G. Meade at the three-day Battle of Gettysburg in Pennsylvania in July; the battle would produce the largest number of casualties in the American Civil War. With some of his subordinates being new and inexperienced in their commands, J.E.B. Stuart's cavalry being out of the area, and Lee being slightly ill, he was less than comfortable with how events were unfolding. While the first day of battle was controlled by the Confederates, key terrain that should have been taken by General Ewell was not. The second day ended with the Confederates unable to break the Union position, and the Union being more solidified. Lee's decision on the third day, against the sound judgment of his best corps commander General Longstreet, to launch a massive frontal assault on the center of the Union line was disastrous. The assault known as Pickett's Charge was repulsed and resulted in heavy Confederate losses. The general rode out to meet his retreating army and proclaimed, "All this has been my fault."[105] Lee was compelled to retreat. Despite flooded rivers that blocked his retreat, he escaped Meade's ineffective pursuit. Following his defeat at Gettysburg, Lee sent a letter of resignation to President Davis on August 8, 1863, but Davis refused Lee's request. That fall, Lee and Meade met again in two minor campaigns that did little to change the strategic standoff. The Confederate Army never fully recovered from the substantial losses incurred during the 3-day battle in southern Pennsylvania. The historian Shelby Foote stated, "Gettysburg was the price the South paid for having Robert E. Lee as commander."

Ulysses S. Grant and the Union offensive

In 1864 the new Union general-in-chief, Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, sought to use his large advantages in manpower and material resources to destroy Lee's army by attrition, pinning Lee against his capital of Richmond. Lee successfully stopped each attack, but Grant with his superior numbers kept pushing each time a bit farther to the southeast. These battles in the Overland Campaign included the Wilderness, Spotsylvania Court House and Cold Harbor.

Grant eventually was able to stealthily move his army across the James River. After stopping a Union attempt to capture Petersburg, Virginia, a vital railroad link supplying Richmond, Lee's men built elaborate trenches and were besieged in Petersburg, a development which presaged the trench warfare of World War I. He attempted to break the stalemate by sending Jubal A. Early on a raid through the Shenandoah Valley to Washington, D.C., but was defeated early on by the superior forces of Philip Sheridan. The Siege of Petersburg lasted from June 1864 until March 1865, with Lee's outnumbered and poorly supplied army shrinking daily because of desertions by disheartened Confederates.

General-in-chief

On January 31, 1865, Lee was promoted to general-in-chief of Confederate forces.

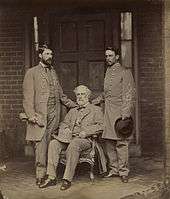

As the South ran out of manpower the issue of arming the slaves became paramount. By late 1864, the army so dominated the Confederacy that civilian leaders were unable to block the military's proposal, strongly endorsed by Lee, to arm and train slaves in Confederate uniform for combat. Lee explained, "We should employ them without delay ... [along with] gradual and general emancipation." The first units were in training as the war ended.[106][107] As the Confederate army was devastated by casualties, disease and desertion, the Union attack on Petersburg succeeded on April 2, 1865. Lee abandoned Richmond and retreated west. Lee then made an attempt to escape to the southwest and join up with Joseph E. Johnston's Army of Tennessee in North Carolina. However, his forces were soon surrounded and he surrendered them to Grant on April 9, 1865, at the Battle of Appomattox Court House.[108] Other Confederate armies followed suit and the war ended. The day after his surrender, Lee issued his Farewell Address to his army.

Lee resisted calls by some officers to reject surrender and allow small units to melt away into the mountains, setting up a lengthy guerrilla war. He insisted the war was over and energetically campaigned for inter-sectional reconciliation. "So far from engaging in a war to perpetuate slavery, I am rejoiced that slavery is abolished. I believe it will be greatly for the interests of the South."[109]

Summaries of Lee's Civil War battles

The following are summaries of Civil War campaigns and major battles where Robert E. Lee was the commanding officer:[110]

| Battle | Date | Result | Opponent | Confederate troop strength | Union troop strength | Confederate casualties | Union casualties | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cheat Mountain | September 11–13, 1861 | Defeat | Reynolds | 5,000 | 3,000 | ~90 | 88 | Lee's first battle of the Civil War. Severely criticized, Lee was nicknamed "Granny Lee". Lee was sent to SC and GA to supervise fortifications.[111] |

| Seven Days | June 25 – July 1, 1862 | Victory

|

McClellan | 95,000 | 91,000 | 20,614 | 15,849 | Lee acquitted himself well, and remained in field command for the duration of the war under the direction of Jefferson Davis. Union troops remained on the Lower Peninsula and at Fortress Monroe, which became a terminus on the Underground Railroad, and the site terming escaped slaves as "contribands", no longer returned to their rebel owners. |

| Second Manassas | August 28–30, 1862 | Victory | Pope | 49,000 | 76,000 | 9,197 | 16,054 | Union forces continued to occupy northern Virginia |

| South Mountain | September 14, 1862 | Defeat | McClellan | 18,000 | 28,000 | 2,685 | 1,813 | Confederates lost control of westernmost Virginian congressional districts which would later be the core counties of West Virginia. |

| Antietam | September 16–18, 1862 | Defeat | McClellan | 52,000 | 75,000 | 13,724 | 12,410 | Confederates lost an opportunity to gain foreign recognition, Lincoln moved forward on his preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. |

| Fredericksburg | December 11, 1862 | Victory | Burnside | 72,000 | 114,000 | 5,309 | 12,653 | With Lee's troops and supplies depleted, Confederates remained in place south of the Rappahannock. Union forces did not withdraw from northern Virginia. |

| Chancellorsville | May 1, 1863 | Victory | Hooker | 57,000 | 105,000 | 12,764 | 16,792 | Union forces withdrew to ring of defenses around Washington, DC. |

| Gettysburg | July 1, 1863 | Defeat | Meade | 75,000 | 83,000 | 23,231 –28,063 | 23,049 | The Confederate army was physically and spiritually exhausted. Meade was criticized for not immediately pursuing Lee's army. This battle become known as the High Water Mark of the Confederacy.[112] Lee would never personally invade the North again after this battle. Rather he was determined to defend Richmond and eventually Petersburg at all costs. |

| Wilderness | May 5, 1864 | Inconclusive | Grant | 61,000 | 102,000 | 11,400 | 18,400 | Lee's tactical victory, yet Grant continued his offensive, circling east and south advancing on Richmond and Petersburg |

| Spotsylvania | May 12, 1864 | Inconclusive[113] | Grant | 52,000 | 100,000 | 12,000 | 18,000 | Although beaten and unable to take Lee's defenses, Grant continued the Union offensive, circling east and south advancing on Richmond and Petersburg |

| Cold Harbor | June 1, 1864 | Victory | Grant | 62,000 | 108,000 | 2,500 | 12,000 | Although Grant was able to continue his offensive, Grant referred to the Cold Harbor assault as his "greatest regret" of the war in his memoirs. |

| Fussell's Mill | August 14, 1864 | Victory | Hancock | 20,000 | 28,000 | 1,700 | 2,901 | Union attempt to break Confederate siege lines at Richmond, the Confederate capital |

| Appomattox Campaign | March 29, 1865 | Defeat | Grant | 50,000 | 113,000 | no record available | 10,780 | General Robert E. Lee surrendered to General Ulysses S. Grant.[114] After the surrender Grant gave Lee's army much-needed food rations, they were paroled to return to their homes, never to take up arms against the Union again. |

After the war

After the war, Lee was not arrested or punished, but he did lose the right to vote as well as some property. Lee supported President Johnson's plan of Reconstruction, but joined with Democrats in opposing the Radical Republicans who demanded punitive measures against the South, distrusted its commitment to the abolition of slavery and, indeed, distrusted the region's loyalty to the United States.[115][116] Lee generally supported civil rights for all, as well as a system of free public schools for blacks, but forthrightly opposed allowing blacks to vote. "My own opinion is that, at this time, they [black Southerners] cannot vote intelligently, and that giving them the [vote] would lead to a great deal of demagogism, and lead to embarrassments in various ways," Lee stated.[117] Emory Thomas says Lee had become a suffering Christ-like icon for ex-Confederates. President Grant invited him to the White House in 1869, and he went. Nationally he became an icon of reconciliation between the North and South, and the reintegration of former Confederates into the national fabric.[118]

Lee's prewar family home, the Custis-Lee Mansion, was seized by Union forces during the war and turned into Arlington National Cemetery. The family was compensated in 1883.[119]

Lee hoped to retire to a farm of his own, but he was too much a regional symbol to live in obscurity. From April to June 1865, he and his family resided in Richmond at the Stewart-Lee House.[120] He accepted an offer to serve as the president of Washington College (now Washington and Lee University) in Lexington, Virginia, and served from October 1865 until his death. The Trustees used his famous name in large-scale fund-raising appeals and Lee transformed Washington College into a leading Southern college expanding its offerings significantly and added programs in commerce, journalism, and integrated the Lexington Law School. Lee was well liked by the students, which enabled him to announce an "honor system" like West Point's, explaining "We have but one rule here, and it is that every student be a gentleman." To speed up national reconciliation Lee recruited students from the North and made certain they were well treated on campus and in town.[121]

Several glowing appraisals of Lee's tenure as college president have survived, depicting the dignity and respect he commanded among all. Previously, most students had been obliged to occupy the campus dormitories, while only the most mature were allowed to live off-campus. Lee quickly reversed this rule, requiring most students to board off-campus, and allowing only the most mature to live in the dorms as a mark of privilege; the results of this policy were considered a success. A typical account by a professor there states that "the students fairly worshipped him, and deeply dreaded his displeasure; yet so kind, affable, and gentle was he toward them that all loved to approach him. ... No student would have dared to violate General Lee's expressed wish or appeal; if he had done so, the students themselves would have driven him from the college."[122]

While at Washington College, Lee told a colleague that the greatest mistake of his life was taking a military education.[123]

President Johnson's amnesty pardons

On May 29, 1865, President Andrew Johnson issued a Proclamation of Amnesty and Pardon to persons who had participated in the rebellion against the United States. There were fourteen excepted classes, though, and members of those classes had to make special application to the President. Lee sent an application to Grant and wrote to President Johnson on June 13, 1865:

Being excluded from the provisions of amnesty & pardon contained in the proclamation of the 29th Ulto; I hereby apply for the benefits, & full restoration of all rights & privileges extended to those included in its terms. I graduated at the Mil. Academy at West Point in June 1829. Resigned from the U.S. Army April '61. Was a General in the Confederate Army, & included in the surrender of the Army of N. Virginia 9 April '65.[124]

On October 2, 1865, the same day that Lee was inaugurated as president of Washington College in Lexington, Virginia, he signed his Amnesty Oath, thereby complying fully with the provision of Johnson's proclamation. Lee was not pardoned, nor was his citizenship restored.[124]

Three years later, on December 25, 1868, Johnson proclaimed a second amnesty which removed previous exceptions, such as the one that affected Lee.[125]

Postwar politics

Lee, who had opposed secession and remained mostly indifferent to politics before the Civil War, supported President Johnson's plan of Presidential Reconstruction that took effect in 1865–66. However, he opposed the Congressional Republican program that took effect in 1867. In February 1866, he was called to testify before the Joint Congressional Committee on Reconstruction in Washington, where he expressed support for President Andrew Johnson's plans for quick restoration of the former Confederate states, and argued that restoration should return, as far as possible, the status quo ante in the Southern states' governments (with the exception of slavery).[126]

Lee told the Committee, "...every one with whom I associate expresses kind feelings towards the freedmen. They wish to see them get on in the world, and particularly to take up some occupation for a living, and to turn their hands to some work." Lee also expressed his "willingness that blacks should be educated, and ... that it would be better for the blacks and for the whites." Lee forthrightly opposed allowing blacks to vote: "My own opinion is that, at this time, they [black Southerners] cannot vote intelligently, and that giving them the [vote] would lead to a great deal of demagogism, and lead to embarrassments in various ways."[127] Lee also recommended the deportation of African Americans from Virginia and even mentioned that Virginians would give aid in the deportation. "I think it would be better for Virginia if she could get rid of them [African Americans]. ... I think that everyone there would be willing to aid it."[128][129]

In an interview in May 1866, Lee said, "The Radical party are likely to do a great deal of harm, for we wish now for good feeling to grow up between North and South, and the President, Mr. Johnson, has been doing much to strengthen the feeling in favor of the Union among us. The relations between the Negroes and the whites were friendly formerly, and would remain so if legislation be not passed in favor of the blacks, in a way that will only do them harm."[130]

In 1868, Lee's ally Alexander H. H. Stuart drafted a public letter of endorsement for the Democratic Party's presidential campaign, in which Horatio Seymour ran against Lee's old foe Republican Ulysses S. Grant. Lee signed it along with thirty-one other ex-Confederates. The Democratic campaign, eager to publicize the endorsement, published the statement widely in newspapers.[131] Their letter claimed paternalistic concern for the welfare of freed Southern blacks, stating that "The idea that the Southern people are hostile to the negroes and would oppress them, if it were in their power to do so, is entirely unfounded. They have grown up in our midst, and we have been accustomed from childhood to look upon them with kindness."[132] However, it also called for the restoration of white political rule, arguing that "It is true that the people of the South, in common with a large majority of the people of the North and West, are, for obvious reasons, inflexibly opposed to any system of laws that would place the political power of the country in the hands of the negro race. But this opposition springs from no feeling of enmity, but from a deep-seated conviction that, at present, the negroes have neither the intelligence nor the other qualifications which are necessary to make them safe depositories of political power."[133]

In his public statements and private correspondence, Lee argued that a tone of reconciliation and patience would further the interests of white Southerners better than hotheaded antagonism to federal authority or the use of violence. Lee repeatedly expelled white students from Washington College for violent attacks on local black men, and publicly urged obedience to the authorities and respect for law and order.[134] In 1869–70 he was a leader in successful efforts to establish state-funded schools for blacks.[135] He privately chastised fellow ex-Confederates such as Jefferson Davis and Jubal Early for their frequent, angry responses to perceived Northern insults, writing in private to them as he had written to a magazine editor in 1865, that "It should be the object of all to avoid controversy, to allay passion, give full scope to reason and to every kindly feeling. By doing this and encouraging our citizens to engage in the duties of life with all their heart and mind, with a determination not to be turned aside by thoughts of the past and fears of the future, our country will not only be restored in material prosperity, but will be advanced in science, in virtue and in religion."[136]

Illness and death

On September 28, 1870, Lee suffered a stroke. He died two weeks later, shortly after 9 a.m. on October 12, 1870, in Lexington, Virginia, from the effects of pneumonia. According to one account, his last words on the day of his death, were "Tell Hill he must come up. Strike the tent",[137] but this is debatable because of conflicting accounts and because Lee's stroke had resulted in aphasia, possibly rendering him unable to speak.

At first no suitable coffin for the body could be located. The muddy roads were too flooded for anyone to get in or out of the town of Lexington. An undertaker had ordered three from Richmond that had reached Lexington, but due to unprecedented flooding from long-continued heavy rains, the caskets were washed down the Maury River. Two neighborhood boys, C.G. Chittum and Robert E. Hillis, found one of the coffins that had been swept ashore. Undamaged, it was used for the General's body, though it was a bit short for him. As a result, Lee was buried without shoes.[138] He was buried underneath Lee Chapel at Washington and Lee University, where his body remains.

Legacy

Among Southerners, Lee came to be even more revered after his surrender than he had been during the war, when Stonewall Jackson had been the great Confederate hero. In an address before the Southern Historical Society in Atlanta, Georgia in 1874, Benjamin Harvey Hill described Lee in this way:

He was a foe without hate; a friend without treachery; a soldier without cruelty; a victor without oppression, and a victim without murmuring. He was a public officer without vices; a private citizen without wrong; a neighbour without reproach; a Christian without hypocrisy, and a man without guile. He was a Caesar, without his ambition; Frederick, without his tyranny; Napoleon, without his selfishness, and Washington, without his reward.[139]

His reputation continued to grow. By the end of the 19th century, his popularity had spread to the North.[140] Lee's admirers have pointed to his character and devotion to duty, and his brilliant tactical successes in battle after battle against a stronger foe.

According to my notion of military history there is as much instruction both in strategy and in tactics to be gleaned from General Lee's operations of 1862 as there is to be found in Napoleon's campaigns of 1796.

Military historians continue to pay attention to his battlefield tactics and maneuvering, though many think he should have designed better strategic plans for the Confederacy. However, it should be noted that he was not given full direction of the Southern war effort until late in the conflict.

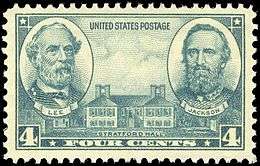

Robert E. Lee has been commemorated on U.S. postage stamps at least five times, the first one being a commemorative stamp that also honored Stonewall Jackson, issued in 1936. A second 'regular issue' stamp was issued in 1955. He was commemorated with a 32-cent stamp issued in the American Civil War Issue of June 29, 1995. His horse Traveller is pictured in the background. Explanatory text is imprinted on the back of each stamp, issued in a sheet of 20 commemorative Civil War stamps. Stamp Ventures printed the stamps in the gravure process. An image of the stamp is available at Arago online at the link in the footnote.[142]

Washington and Lee University in Lexington, Virginia was commemorated on its 200th anniversary on November 23, 1948, with a 3-cent postage. The central design is a view of the university, flanked by portraits of generals George Washington and Robert E. Lee.[143] Lee was again commemorated on a commemorative stamp in 1970, along with Jefferson Davis and Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson, depicted on horseback on the 6-cent Stone Mountain Memorial commemorative issue, modeled after the actual Stone Mountain Memorial carving in Georgia. The stamp was issued on September 19, 1970 in conjunction with the dedication of the Stone Mountain Confederate Memorial in Georgia on May 9, 1970. The design of the stamp replicates the memorial, the largest high relief sculpture in the world. It is carved on the side of Stone Mountain 400 feet above the ground.[144]

Barracks at West Point built in 1962 are named after him.

On September 29, 2007, General Lee's three Civil War-era letters were sold for $61,000 at auction by Thomas Willcox, much less than the record of $630,000 for a Lee item in 2002. The auction included more than 400 documents of Lee's from the estate of the parents of Willcox that had been in the family for generations. South Carolina sued to stop the sale on the grounds that the letters were official documents and therefore property of the state, but the court ruled in favor of Willcox.[145]

On January 30, 1975, Senate Joint Resolution 23, A joint resolution to restore posthumously full rights of citizenship to General R. E. Lee was introduced into the Senate by Senator Harry F. Byrd, Jr. (I-VA), the result of a five-year campaign to accomplish this. The resolution, which enacted Public Law 94-67, was passed, and the bill was signed by President Gerald Ford on September 5.[146][147][148]

Monuments, memorials and commemorations

Since it was built in 1884, the most prominent monument in New Orleans has been a 60-foot (18 m)-tall monument to General Lee. A 16.5-foot (5.0 m) statue of Lee stands tall upon a towering column of white marble in the middle of Lee Circle. The statue of Lee, which weighs more than 7,000 pounds, faces the North. Lee Circle is situated along New Orleans' famous St. Charles Avenue. The New Orleans streetcars roll past Lee Circle and New Orleans' best Mardi Gras parades go around Lee Circle (the spot is so popular that bleachers are set up annually around the perimeter for Mardi Gras). Around the corner from Lee Circle is New Orleans' Confederate Museum, which contains the second largest collection of Confederate memorabilia in the world.[149] In a tribute to Lee Circle (which had formerly been known as Tivoli Circle), former Confederate soldier George Washington Cable wrote:

In Tivoli Circle, New Orleans, from the centre and apex of its green flowery mound, an immense column of pure white marble rises in the ... majesty of Grecian proportions high up above the city's house-tops into the dazzling sunshine ... On its dizzy top stands the bronze figure of one of the worlds greatest captains. He is alone. Not one of his mighty lieutenants stand behind, beside or below him. His arms are folded on that breast that never knew fear, and his calm, dauntless gaze meets the morning sun as it rises, like the new prosperity of the land he loved and served so masterly, above the far distant battle fields where so many thousands of his gray veterans lie in the sleep of fallen heroes. (Silent South, 1885, The Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine)

Arlington House, The Robert E. Lee Memorial, also known as the Custis–Lee Mansion,[150][151] is a Greek revival mansion in Arlington, Virginia, that was once Lee's home. It overlooks the Potomac River and the National Mall in Washington, D.C. During the Civil War, the grounds of the mansion were selected as the site of Arlington National Cemetery, in part to ensure that Lee would never again be able to return to his home. The United States designated the mansion as a National Memorial to Lee in 1955, a mark of widespread respect for him in both the North and South.[152]

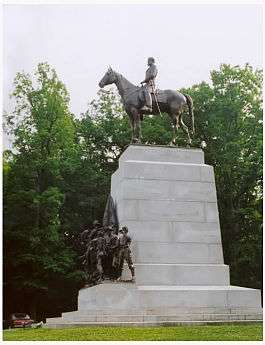

In Richmond, Virginia, a large equestrian statue of Lee by French sculptor Jean Antonin Mercié is the centerpiece of the city's famous Monument Avenue, which boasts four other statues to famous Confederates. This monument to Lee was unveiled on May 29, 1890; over 100,000 people attended this dedication. Lee is also shown mounted on Traveller in Gettysburg National Military Park on top of the Virginia Monument; he is facing roughly in the direction of Pickett's Charge. Lee's portrayal on a mural on Richmond's Flood Wall on the James River, considered offensive by some, was removed in the late 1990s, but currently is back on the flood wall. Also in Virginia, the Robert Edward Lee Sculpture at Charlottesville was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1997.[153]

In Baltimore's Wyman Park, a large double equestrian statue of Lee and Jackson is located directly across from the Baltimore Museum of Art. Designed by Laura Gardin Fraser and dedicated in 1948, Lee is depicted astride his horse Traveller next to Stonewall Jackson who is mounted on "Little Sorrel." Architect John Russell Pope created the base, which was dedicated on the anniversary of the eve of the Battle of Chancellorsville.[154] The Baltimore area of Maryland is also home to a large nature park called Robert E. Lee Memorial Park.

An equestrian statue of Lee is located in Robert E. Lee Park, in Dallas; and in Austin, a statue of Lee is on display at the main mall of the University of Texas at Austin. A statue of Robert E. Lee is one of two statues (the other is Washington) representing Virginia in Statuary Hall in the Capitol in Washington, D.C. Lee is one of the figures depicted in bas-relief carved into Stone Mountain near Atlanta. Accompanying him on horseback in the relief are Stonewall Jackson and Jefferson Davis.[155]

The birthday of Robert E. Lee is celebrated or commemorated in several states. In Virginia, Lee–Jackson Day is celebrated on the Friday preceding Martin Luther King, Jr. Day which is the third Monday in January.[156] In Texas, he is celebrated as part of Confederate Heroes Day on January 19, Lee's birthday.[157] In Alabama, Arkansas, and Mississippi, his birthday is celebrated on the same day as Martin Luther King, Jr. Day,[158][159][160] while in Georgia, this occurs on the day after Thanksgiving.[161]

One United States college and one junior college are named for Lee: Washington and Lee University in Lexington, Virginia; and Lee College in Baytown, Texas, respectively. Lee Chapel at Washington and Lee University marks Lee's final resting place. Throughout the South, many primary and secondary schools were also named for him as well as private schools such as Robert E. Lee Academy in Bishopville, South Carolina.

In 1900, Lee was one of the first 29 individuals selected for the Hall of Fame for Great Americans (the first Hall of Fame in the United States), designed by Stanford White, on the Bronx, New York, campus of New York University, now a part of Bronx Community College.[162][163]

Robert E Lee Monument, Charlottesville, Virginia, Leo Lentelli, sculptor, 1924

Robert E Lee Monument, Charlottesville, Virginia, Leo Lentelli, sculptor, 1924 Robert E Lee, Virginia Monument, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, Frederick William Sievers, sculptor, 1917

Robert E Lee, Virginia Monument, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, Frederick William Sievers, sculptor, 1917 Lee by Mercié, Monument Avenue, Richmond, Virginia, 1890

Lee by Mercié, Monument Avenue, Richmond, Virginia, 1890 Statue of Lee on the grounds of the University of Texas at Austin

Statue of Lee on the grounds of the University of Texas at Austin Statue of Lee in Dallas, Texas

Statue of Lee in Dallas, Texas

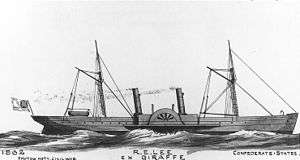

In 1862, the newly formed Confederate Navy purchased a 642-ton iron-hulled side-wheel gunboat, built in at Glasgow, Scotland, and gave her the name of CSS Robert E. Lee in honor of this Confederate General. During the next year, she became one of the South's most famous Confederate blockade runners, successfully making more than twenty runs through the Union blockade.[164]

The Mississippi River steamboat Robert E. Lee was named for Lee after the Civil War. It was the participant in an 1870 St. Louis – New Orleans race with the Natchez VI, which was featured in a Currier and Ives lithograph. The Robert E. Lee won the race.[165] The steamboat inspired the 1912 song Waiting for the Robert E. Lee by Lewis F. Muir and L. Wolfe Gilbert.[166] In more modern times, the USS Robert E. Lee, a George Washington-class ballistic missile submarine built in 1958, was named for Lee,[167] as was the M3 Lee tank, produced in 1941 and 1942.

The Commonwealth of Virginia issues an optional license plate honoring Lee, making reference to him as 'The Virginia Gentleman'.[168] In February 2014, a road on Fort Bliss previously named for Lee was renamed to honor Buffalo Soldiers.[169][170]

A recent biographer, Jonathan Horn, outlines the unsuccessful efforts in Washington to memorialize Lee in the naming of the Arlington Memorial Bridge after both Grant and Lee.[171]

In popular culture

Lee serves as a main character in the Shaara Family novels The Killer Angels (Gettysburg), Gods and Generals, and The Last Full Measure, as well as the film adaptations of Gettysburg and Gods and Generals. He is played by Martin Sheen in the former and his descendant Robert Duvall in the latter. Lee is portrayed as a hero in the historical children's novel Lee and Grant at Appomattox by MacKinlay Kantor. His part in the Civil War is told from the perspective of his horse in Richard Adams' book Traveller.

Lee is an obvious subject for American Civil War alternate histories. Ward Moore's Bring the Jubilee, Kantor's If the South Had Won the Civil War (1960), and Harry Turtledove's The Guns of the South, all have Lee ending up as President of a victorious Confederacy and freeing the slaves (or laying the groundwork for the slaves to be freed in a later decade). Although Bring and If relegate him to a set of passing references, Lee is more of a main character in the Guns. He is also the prime character of Turtledove's "Lee at the Alamo," which can be read on-line,[172] and sees the opening of the Civil War drastically altered so as to affect Lee's personal priorities considerably. Turtledove's "War Between the Provinces" series is an allegory of the Civil War told in the language of fairy tales, with Lee appearing as a knight named "Duke Edward of Arlington." Lee is also a knight in "The Charge of Lee's Brigade" in Alternate Generals volume 1, written by Turtledove's friend S.M. Stirling and featuring Lee, whose Virginia is still a loyal British colony, fighting for the Crown against the Russians in Crimea. In Lee Allred's "East of Appomattox" in Alternate Generals volume 3, Lee is the Confederate Minister to London circa 1868, desperately seeking help for a CSA which has turned out poorly suited to independence. Robert Skimin's Grey Victory features Lee as a supporting character preparing to run for the presidency in 1867.

On September 18, 1960, the American actor George Macready portrayed Lee in the episode "Johnny Yuma at Appomattox" of the ABC television series The Rebel, starring Nick Adams in the title role.[173]

Robert Symonds played Lee in the 1982 miniseries The Blue and the Gray .

In the 1986 TV series North and South Book II , Lee was portrayed by actor William Schallert .

The Dodge Charger featured in the CBS television series The Dukes of Hazzard was named The General Lee.[174][175] In the 2005 film based on this series, the car drives past a statue of the General, and its drivers salute him.

Dates of Rank

| Rank | Date | Unit | Component |

|---|---|---|---|

| July 1, 1829[176] | Corps of Engineers | United States Army | |

| September 21, 1836[177] | Corps of Engineers | United States Army | |

| August 7, 1838[177] | Corps of Engineers | United States Army | |

| April 18, 1847[177] | Corps of Engineers | United States Army | |

| August 20, 1847[177] | Corps of Engineers | United States Army | |

| September 13, 1847[178] | Corps of Engineers | United States Army | |

| March 3, 1855[178] | 2nd Cavalry Regiment | United States Army | |

| March 16, 1861[178] | 1st Cavalry Regiment | United States Army | |

| Major General | April 22, 1861[179] | Virginia Militia | |

| May 14, 1861[180] | Confederate States Army | ||

| June 14, 1861[181] | Confederate States Army | ||

| January 23, 1865[182] | Confederate States Army |

- § Breveted for conduct in the Battle of Cerro Gordo

- † Breveted for conduct in Battles of Contreras and Churubusco

- ‡ Breveted for conduct in Battle of Chapultepec

See also

References

- ↑ Pryor, Elizabeth Brown (2008). "Robert E. Lee's 'Severest Struggle'". American Heritage.

- ↑ Bunting, Josiah (2004). Ulysses S. Grant. New York: Time Books. p. 62. ISBN 9780805069495.

- ↑ Jay Luvaas, "Lee and the Operational Art: The Right Place, the Right Time," Parameters: US Army War College, Sept 1992, Vol. 22#3 pp. 2-18

- ↑ McPherson, James M. (1988). Battle Cry of Freedom: the Civil War Era. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 538, 650. ISBN 9780195168952.