Robert Townsend (spy)

| Robert Townsend | |

|---|---|

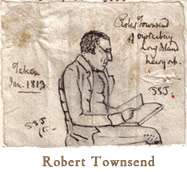

Only surviving portrait of Robert Townsend | |

|

| |

| Born | November 25, 1753 |

| Died | March 7, 1838 (aged 84) |

| Nationality | American |

| Religion | Quaker |

| Children | Robert Townsend, Jr. |

Robert Townsend (November 25, 1753 – March 7, 1838)[1][2] was a member of the Culper Ring during the American Revolution. Townsend operated in New York City with the aliases “Samuel Culper, Jr.” and “723,” and gathered information as a service to General George Washington. He is one of the least known operatives in the spy ring, once demanding that Abraham Woodhull (aka “Samuel Culper”) never tell his name to anyone, not even Washington.[3]

Background

Townsend was the third son of eight children of Samuel and Sarah Townsend from Oyster Bay, New York. Samuel was a Whig-slanted politician who owned a store in Oyster Bay. Little is known about Robert’s early life. His mother was an Episcopalian and his father was a liberal Quaker. He held patriotic feelings towards his country but was a Loyalist. Robert matured in an atmosphere in which his father routinely acted in ways that were considered dangerous by traditional Quakers.[4]

Despite his father’s political battles, young Robert showed little interest in public service. Samuel arranged for Robert to apprentice during his mid-teens with the House of Templeton & Stewart, a merchant firm. During this time, Robert lived and worked among soldiers and residents of Holy Ground,[5] New York City’s biggest red light district.[6] Templeton & Stewart catered to the working-class residents of this district. Ultimately, Townsend’s early years were dedicated to making a fortune and not demonstrating his underlying patriotism, which would have undermined his financial goals.[7]

Townsend fared well during the war in financial terms, operating a store even as he was spying for Washington. Between May 1781 and July 1783, he brought in £16,786, while his expenditures amounted to £15,161, for a profit of £1,625 over that span of time.[8]

Into the Spy Ring

A number of factors led Townsend to the Culper Spy Ring, including the influence of Thomas Paine’s Common Sense, British harassment of his family, and his relationship with Woodhull.

Townsend's Quaker upbringing placed him at odds with the thought of fighting the British forces occupying America. Strict Quaker philosophy called for an adherence to pacifism. In this case, violence was prohibited. However, Pennsylvania experienced a break between "political" Quakers and "religious" Quakers during the 1750s. Essentially, the latter accused the former of breaking with traditional values, resulting in the resigning of "political" Quakers from office and leading to a wave of purification within the Quaker movement. The renewed and obedient Quakers pledged to embrace non-violence and to never revolt against a legal government. Thus, Quakers emerged as the strongest supporters of British rule.[9]

Townsend was torn between his moderate-Quaker upbringing and this fervent Quaker revival, but he ultimately turned his back on pacifism as a result of Thomas Paine's pamphlet Common Sense. Paine had also been brought up in the Quaker tradition, and he advocated in Common Sense the early Quaker views of struggling against corruption and narcissism. However, Paine also advocated resistance as the means to achieve those goals, putting him directly at odds with the newly reformed Quaker movement. Paine argued that the pacifists-at-any-price were not authentic Quakers. His pamphlet inspired a small number of Quakers to join the struggle against Britain, including Townsend. Thus, a few months after Paine's pamphlet was published, Townsend volunteered for a logistics post in the Continental Army, which would not require him to kill.[10]

Another factor that led to Townsend joining the fight against British rule was the treatment of his family by British soldiers in Oyster Bay. A number of British officers thought that anti-British sentiment had been ingrained into the colonists' spirit, and they believed that "it should be thrash'd out of them [because] New England has poyson'd the whole."[11] This led to numerous incidents of violence and pillage directed at colonists. On November 19, 1778, one such instance drove Townsend to the Patriot cause.[12] Colonel John Graves Simcoe of the Queen's Rangers and roughly 300 of his men were stationed in Oyster Bay during the winter months. Simcoe took the Townsend home as his headquarters, and he and his men used the home when and however they wanted. Townsend's father Samuel was distraught after his prized apple orchard was torn down by Simcoe's men. Adding to the insult, the Townsends were forced to swear allegiance to the King or go to prison.[13]

A final factor was Townsend's relationship with Abraham Woodhull. Woodhull knew Townsend as a result of their both lodging at a boarding house run by Woodhull's brother-in-law. Woodhull was also a descendant of Oyster Bay's founder Captain John Underhill, and Townsend may have been directed to the boardinghouse by Underhill. Woodhull may have also known about Townsend's father's Whiggish political beliefs, as he was well known throughout Long Island.[14] Woodhull as a recruiter, and Townsend as the recruited, knew and trusted each other well enough by June 1779, that Townsend eagerly accepted when Woodhull made his pitch to Townsend to join a new spy ring for Washington.[15]

Washington's intentions for Townsend

These are George Washington's instructions for Woodhull (Culper, Sr.) and Townsend (Culper, Jr.)

Culper Junior, to remain in the City, to collect all the useful information he can-to do this he should mix as much as possible among the officers and refugees, visit the coffee houses, and all public places. He is to pay particular attention to the movements by land and water in and about the city especially. How their transports are secured against attempt to destroy them-whether by armed vessels upon the flanks, or by chains, booms, or any contrivances to keep off fire rafts.

The number of men destined for the defense of the City and environs, endeavoring to designate the particular corps, and where each is posted.

To be particular in describing the place where the works cross the island in the rear of the City-and how many redoubts are upon the line from the river to river, how many Cannon in each, and of what weight and whether the redoubts are closed or open next the city.

Whether there are any works upon the Island of New York between those near the City and the works at Fort Knyphausen or Washington, and if any, whereabouts and of what kind.

To be very particular to find out whether any works are thrown up on Harlem River, near Harlem Town, and whether Horn's Hook is fortified. If so, how many men are kept at each place, and what number and what sized cannon are in those works.

To enquire whether they have dug pits within and in front of the lines and works in general, three or four feet deep, in which sharp pointed stakes are pointed. These are intended to receive and wound men who attempt a surprise at night.

The state of the provisions, forage and fuel to be attended to, as also the health and spirits of the Army, Navy and City.

These are the principal matters to be observed within the Island and about the City of New York. Many more may occur to a person of C. Junr's penetration which he will note and communicate.

Culper Senior's station to be upon Long Island to receive and transmit the intelligence of Culper Junior...

There can be scarcely any need of recommending the greatest caution and secrecy in a business so critical and dangerous. The following seem to be the best general rules: To entrust none but the persons fixed upon to transmit the business. To deliver the dispatches to none upon our side but those who shall be pitched upon for the purpose of receiving them and to transmit them and any intelligence that may be obtained to no one but the Commander-in-Chief.[16]

As "Culper, Jr."

Wasting little time to begin spy activities, Townsend sent his first dispatch on June 19, 1779 — nine days after Woodhull informed Washington that he had a contact in New York. This first piece of intelligence was designed to look like a letter between two Loyalists. In it, Townsend stated that he received information from a Rhode Islander who gathered from British troops that two British divisions "are to make excursion into Connecticut...and very soon."[17]

Counterfeiting plot discovery

One of Townsend's most valuable and memorable discoveries concerned a plot by the British to ruin the American economy by flooding the country with counterfeit dollars. American political and military leaders were well aware of these intentions and understood the potential ramifications of a worthless dollar. In early 1780, Townsend received some intelligence about the British belief that the war would not last much longer as a result of a disastrous depreciation of the dollar.

The most crucial part of Townsend's report was that the British had procured "several reams of paper made for the last emission struck by Congress." This was terrible news for American leaders: the British had previously been forced to counterfeit money on paper that was similar to the official paper, but now they had the authentic paper. Thus, distinguishing between real and fake money would be virtually impossible. As a result, Congress was forced to recall all its bills in circulation—a major ordeal, but one that saved the war-effort by not allowing counterfeit money to flood the market.[18]

Counterintelligence

Townsend warned his superiors of spies in their midst. At one point, he warned Benjamin Tallmadge that Christoper Duychenik was an agent of New York City Mayor David Mathews. Townsend warned that Mathews was under the direction of Governor William Tryon. Townsend also believed that if these men found out about the intelligence report, they would immediately suspect Townsend, indicating Townsend's potential association with high-level officials.[19]

Disinformation

After the French had joined the war on the side of the colonists, a French fleet was set to land and disembark troops at Newport, Rhode Island. The problem with this plan was that the British controlled Long Island and New York City and had large amounts of influence in Long Island Sound. The British got wind of the French plans and began preparing to intercept the smaller French fleet before the French soldiers could make landfall. George Washington learned of the British plans through the Culper Spy Ring, and he was able to successfully bluff the British forces into believing that an attack was planned on New York City, feeding the enemy false information on his plans. Thus, Washington was able to keep the British occupied while the French were able to safely land their forces.[20]

Suspicion

A number of events caused Townsend to become extremely suspicious and led to his using great caution regarding spy activities.

One involved his nephew, James Townsend. After Washington and Woodhull had a brief falling-out, James became the new courier between Robert and Tallmadge. James' cover story was that he was a Tory visiting family in rebel-controlled territory and was seeking to recruit men for the British army. When James visited the Deausenberry family, he acted the part well enough to convince the secret Patriots that he was really a Tory. John Deausenberry dragged James to the local Patriot headquarters, but after Washington's personal intervention, James was set free. This event not only caused anger towards his nephew for Robert, but illustrated how easy it was to get caught. As a result of this event, Townsend often refused to report intelligence in writing for the remainder of his spying career.[21]

Another event revolved around the arrest of Hercules Mulligan by Benedict Arnold (by then serving the British). Mulligan eventually became an agent of the Culper Ring and was responsible for a number of intelligence reports. Mulligan had previously been arrested for agitating anti-British sentiment, and Arnold had him arrested for having questionable American contacts. Although he was released after no evidence showed him to be a spy, his short captivity further convinced Townsend of the dangers he faced. This event led Tallmadge to direct Culper Ring activities more towards tactical intelligence for Tallmadge's dragoons rather than undercover operations in New York.[22]

Final Culper report

As the end of the war drew near, and American forces focused on Yorktown and Lord Charles Cornwallis, the Culper Ring became less significant for Washington. However, even after the British Parliament overruled King George III and ordered a cessation of arms, Washington remained skeptical of British intentions. Reports suggested that British forces in New York still continued to fortify their lines. Nevertheless, Culper activity was limited and ended for a short time. However, when a British delegate reached Paris in 1782 to discuss peace negotiations, Washington reactivated the Ring. Upon this request to reactivate, Townsend wrote what is likely his last report on September 19, 1782:

The last packet...has indeed brought the clearest and unequivocal Proofs that the independence of America is unconditionally to be acknowledged, nor will there be any conditions insisted on for those who have joined the King's Standard...Sir Guy himself says that he thinks it not improbable that the next Packet may bring orders for an evacuation of N. York.

A fleet is getting ready to sail for the Bay of Fundy about the first of October to transport a large number of Refugees to that Quarter...Indeed, I never saw such general distress and dissatisfaction in my life as is painted in the countenance of every Tory at N.Y.[23]

Life after the Culper Ring

After the war, Townsend ended his business connections in New York and moved back to Oyster Bay. Townsend never married, sharing his family's home and growing old with his sister Sally.[24]

Townsend likely had a son, Robert Townsend, Jr., and it is unclear who the child's mother was. One possibility is Townsend's housekeeper, Mary Banvard, whom Robert Sr. left $500 in his will.[25] Another possibility is that the mother was a Culper Ring member known today only as Agent 355,[24] however this possibility is unlikely.[26] Questions remain about whether Robert, Jr. was indeed Townsend's son. Solomon Townsend once claimed that Townsend's brother, William, was actually the father.[25]

Robert Townsend died on March 7, 1838, at the age of eighty-four. He managed to take his alternate identity to the grave. The identity of Samuel Culper, Jr. was discovered in 1930 by New York historian Morton Pennypacker.[27] The Townsend home in Oyster Bay is now a museum known as the Raynham Hall Museum.

In popular culture

- Robert Townsend is portrayed by actor Nick Westrate on the AMC period drama Turn: Washington's Spies.

- Robert Townsend is in the television show White Collar in the episode "Identity Crisis"

See also

- Intelligence in the American Revolutionary War

- Intelligence operations in the American Revolutionary War

Notes

- ↑ Alexander Rose. “Washington’s Spies." (New York: Bantam Dell, 2006) 135

- ↑ Alexander Rose. “Washington’s Spies." (New York: Bantam Dell, 2006) 277

- ↑ Lynn Groh. “The Culper Spy Ring.” (Philadelphia: The Westminster Press, 1969) 13

- ↑ Alexander Rose. "Washington’s Spies." (New York: Bantam Dell, 2006) 133-143

- ↑ http://www.cathleenschine.com/journalism/ny_ground/

- ↑ http://www.oldsaltblog.com/2008/10/the-holy-ground-songs-sailors-and-women-of-easy-virtue/

- ↑ Alexander Rose. "Washington’s Spies." (New York: Bantam Dell, 2006) 143

- ↑ Alexander Rose, "Washington's Spies." (New York: Bantum Dell) 154

- ↑ Alexander Rose. Washington's Spies." (New York: Bantum Dell) 154-155

- ↑ Alexander Rose. Washington's Spies." (New York: Bantum Dell) 156-158

- ↑ Alexander Rose. Washington's Spies." (New York: Bantum Dell) 160

- ↑ Alexander Rose. Washington's Spies." (New York: Bantum Dell) 161

- ↑ Lynn Groh. “The Culper Spy Ring.” Philadelphia: The Westminster Press, 1969) 16-17

- ↑ Alexander Rose. Washington's Spies." (New York: Bantum Dell) 133

- ↑ Alexander Rose. Washington's Spies." (New York: Bantum Dell) 1164

- ↑ Alexander Rose. Washington's Spies." (New York: Bantum Dell) 176-178

- ↑ Alexander Rose. Washington's Spies." (New York: Bantum Dell) 164-165

- ↑ Alexander Rose. Washington's Spies." (New York: Bantum Dell) 179-184

- ↑ Alexander Rose. Washington's Spies." (New York: Bantum Dell) 170

- ↑ http://raynhamhallmuseum.org/history.asp

- ↑ Alexander Rose. Washington's Spies." (New York: Bantum Dell) 185-187

- ↑ Alexander Rose. Washington's Spies." (New York: Bantum Dell) 226-227

- ↑ Lynn Groh. “The Culper Spy Ring.” (Philadelphia: The Westminster Press, 1969) 131-132

- 1 2 Lynn Groh. “The Culper Spy Ring.” (Philadelphia: The Westminster Press, 1969) 133

- 1 2 Alexander Rose. Washington's Spies." (New York: Bantum Dell) 276

- ↑ The Mystery of Agent 355

- ↑ Lynn Groh. “The Culper Spy Ring.” (Philadelphia: The Westminster Press, 1969) 134