Russian political jokes

Russian political jokes (or, rather, Russophone political jokes) are a part of Russian humour and can be naturally grouped into the major time periods: Imperial Russia, Soviet Union and finally post-Soviet Russia. Quite a few political themes can be found among other standard categories of Russian joke, most notably Rabinovich jokes and Radio Yerevan.

Imperial Russia

In Imperial Russia, most political jokes were of the polite variety that circulated in educated society. Few of the political jokes of the time are recorded, but some were printed in a 1904 German anthology.[1]

- A man was reported to have said: "Nikolay is a moron!" and was arrested by a policeman. "No, sir, I meant not our respected Emperor, but another Nikolay!" - "Don't try to trick me: if you say "moron", you are obviously referring to our tsar!"

- A respected merchant, Sevenassov, wants to change his surname, and asks the Tsar for permission. The Tsar gives his decision in writing: "Permitted to subtract two asses".

There were also numerous politically themed Chastushki in Imperial Russia.

Soviet Union

Every nation enjoys political jokes, but in the Soviet Union telling political jokes could be regarded as type of extreme sport: according to Article 58 (RSFSR Penal Code), "anti-Soviet propaganda" was a potentially capital offense.

- A judge walks out of his chambers laughing his head off. A colleague approaches him and asks why he is laughing. "I just heard the funniest joke in the world!" "Well, go ahead, tell me!" says the other judge. "I can't – I just gave someone ten years for it!"

Ben Lewis claims that the political conditions in the Soviet Union were responsible for the unique humour produced there;[2][3] according to him, "Communism was a humour-producing machine. Its economic theories and system of repression created inherently amusing situations. There were jokes under fascism and the Nazis too, but those systems did not create an absurd, laugh-a-minute reality like communism."

Early Soviet times

Jokes from these times have a certain historical value, depicting the character of the epoch almost as well as long novels might.

- Midnight Petrograd... A Red Guards night watch spots a shadow trying to sneak by. "Stop! Who goes there? Documents!" The frightened person chaotically rummages through his pockets and drops a paper. The Guards chief picks it up and reads slowly, with difficulty: "U.ri.ne A.na.ly.sis"... "Hmm... a foreigner, sounds like ..." "A spy, looks like.... Let's shoot him on the spot!" Then he reads further: "'Proteins: none, Sugars: none, Fats: none...' You are free to go, proletarian comrade! Long live the World revolution!"

Communism

According to Marxist–Leninist theory, communism in the strict sense is the final stage of evolution of a society after it has passed through the socialism stage. The Soviet Union thus cast itself as a socialist country trying to build communism, which was supposed to be a classless society.

- The principle of the state capitalism of the period of transition to communism: the authorities pretend they are paying wages, workers pretend they are working. Alternatively, "So long as the bosses pretend to pay us, we will pretend to work." This joke persisted essentially unchanged through the 1980s.

Satirical verses and parodies made fun of official Soviet propaganda slogans.

- "Lenin has died, but his cause lives on!" (An actual slogan.)

- Punchline variant #1: Rabinovich notes: "I would prefer it the other way round."

- Variant #2: "What a coincidence: Brezhnev has died, but his body lives on". (An allusion to Brezhnev's mental feebleness coupled with the medically assisted staving off of his death. Additional comedic effect in the second variant is produced by the fact that the words 'cause' (delo) and 'body' (telo) rhyme in Russian.)

- Lenin coined a slogan about how communism would be achieved thanks to Communist Party rule and the modernization of the Russian industry and agriculture: "Communism is Soviet power plus electrification of the whole country!" The slogan was subjected to mathematical scrutiny by the people: "Consequently, Soviet power is communism minus electrification, and electrification is communism minus Soviet power."

- A chastushka ridiculing the tendency to praise the Party left and right:

- The winter's passed,

- The summer's here.

- For this we thank

- Our party dear!

Russian:

- Прошла зима,

- настало лето.

- Спасибо партии

- за это!

(Proshla zima, nastalo leto / Spasibo partii za eto!)

- One old bolshevik says to another: "No, my friend, we will not live long enough to see communism, but our children... our poor children!" (An allusion to the slogan, "Our children will live in Communism!")

Some jokes allude to notions long forgotten. These relics are still funny, but may look strange.

- Q: Will there be KGB in communism?

- A: As you know, under communism, the state will be abolished, together with its means of suppression. People will know how to self-arrest themselves.

- The original version was about the Cheka. To fully appreciate this joke, a person must know that during the Cheka times, in addition to the standard taxation to which the peasants were subjected, the latter were often forced to perform samooblozhenie ("self-taxation") – after delivering a normal amount of agricultural products, prosperous peasants, especially those declared to be kulaks were expected to "voluntarily" deliver the same amount again; sometimes even "double samooblozhenie" was applied.

- Q: How do you deal with mice in the Kremlin?

- A: Put up a sign saying "collective farm". Then half the mice will starve, and the rest will run away.[4]

This joke is an allusion to the consequences of the collectivization policy pursued by Joseph Stalin between 1928 and 1933.

Gulag

- Three men are sitting in a cell in the (KGB headquarters) Dzerzhinsky Square. The first asks the second why he has been imprisoned, who replies, "Because I criticized Karl Radek." The first man responds, "But I am here because I spoke out in favor of Radek!" They turn to the third man who has been sitting quietly in the back, and ask him why he is in jail. He answers, "I'm Karl Radek." (A variation of this joke substitutes "Former premier" for "Karl Radek".)

- Armenian Radio was asked: "Is it true that conditions in our labor camps are excellent?" Armenian Radio answers: "It is true. Five years ago a listener of ours raised the same question and was sent to one, reportedly to investigate the issue. He hasn't returned yet; we are told that he liked it there."

- "Comrade Brezhnev, is it true that you collect political jokes?" – "Yes" – "And how many have you collected so far?" – "Three and a half labor camps." (Compare with a similar East German joke about Stasi.)

Gulag Archipelago

Alexander Solzhenitsyn's book Gulag Archipelago has a chapter entitled "Zeks as a Nation", which is a mock ethnographic essay intended to "prove" that the inhabitants of the Gulag Archipelago constitute a separate nation according to "the only scientific definition of nation given by comrade Stalin". As part of this research, Solzhenitsyn analyzes the humor of zeks (gulag inmates). Some examples:[5]

- "He was sentenced to three years, served five, and then he got lucky and was released ahead of time." (The joke alludes to the common practice described by Solzhenitsyn of arbitrarily extending the term of a sentence or adding new charges.) In a similar vein, when someone asked for more of something, e.g. more boiled water in a cup, the typical retort was, "The prosecutor will give you more!" (In Russian: "Прокурор добавит!")

- "Is it hard to be in the gulag?" – "Only for the first 10 years."

- When the quarter-century term had become the standard sentence for contravening Article 58, the standard joke was: "OK, now 25 years of life are guaranteed for you!"

Armenian Radio

The Armenian Radio or "Radio Yerevan" jokes have the format, "ask us whatever you want, we will answer you whatever we want". They supply snappy or ambiguous answers to questions on politics, commodities, the economy or other subjects that were taboo during the Communist era. Questions and answers from this fictitious radio station are known even outside Russia.

- Q: What's the difference between a capitalist fairy tale and a Marxist fairy tale?

- A: A capitalist fairy tale begins, "Once upon a time, there was....". A Marxist fairy tale begins, "Some day, there will be...."

- Q: Is it true that there is freedom of speech in the Soviet Union, just like in the USA?

- A: In principle, yes. In the USA, you can stand in front of the White House in Washington, DC, and yell, "Down with Reagan!", and you will not be punished. Equally, you can also stand in Red Square in Moscow and yell, "Down with Reagan!", and you will not be punished. (A variation of this joke substitutes Richard Nixon for Ronald Reagan.)

- Q: What is the difference between the Constitutions of the USA and USSR? Both of them guarantee freedom of speech.

- A: Yes, but the Constitution of the USA also guarantees freedom after the speech.[6]

- Q: Is it true that the Soviet Union is the most progressive country in the world?

- A: Of course! Life was already better yesterday than it's going to be tomorrow!

Political figures

Politicians have no stereotype as such in Russian culture. Instead, historical and contemporary Russian leaders are portrayed with an emphasis on their unique characteristics. Nevertheless, quite a few jokes of them are reworkings of jokes made about earlier generations of leaders.

- Vladimir Lenin, Joseph Stalin, Nikita Khrushchev and Leonid Brezhnev are all travelling together in a railway carriage. Unexpectedly, the train stops. Lenin suggests: "Perhaps we should announce a subbotnik, so that workers and peasants will fix the problem." Stalin puts his head out of the window and shouts, "If the train does not start moving, the driver will be shot!" (An allusion to the Great Purge.) But the train doesn't start moving. Khrushchev then shouts, "Let's take the rails from behind the train and use them to lay the tracks in front". (An allusion to Khrushchev's various reorganizations.) But still the train doesn't move. Then Brezhnev says, "Comrades, Comrades, let's draw the curtains, turn on the gramophone and pretend we're moving!" (An allusion to the Brezhnev stagnation period.) A later continuation to this has Mikhail Gorbachev saying, "We were going the wrong way anyways!" and changing the train's direction (alluding to his policies of glasnost and perestroika), and Boris Yeltsin driving the train off the rails and through a field (allusion to the breakup of the Soviet Union). (A variation has Stalin, Khrushchev, and Brezhnev on the stopped train; Stalin has the train crew shot, Khrushchev "rehabilitates" the dead men, and Brezhnev pulls down the window shade and pretends the train is moving again.)

Lenin

Jokes about Vladimir Lenin, the leader of the Russian Revolution of 1917, typically made fun of characteristics popularized by propaganda: his supposed kindness, his love of children (Lenin never had children of his own), his sharing nature, his kind eyes, etc. Accordingly, in jokes Lenin is often depicted as sneaky and hypocritical. A popular joke set-up is Lenin interacting with the head of the secret police, Felix Edmundovich Dzerzhinsky, in the Smolny Institute, the seat of the revolutionary communist government in Petrograd, or with khodoki, peasants who came to see Lenin.

- During the famine of the civil war, a delegation of starving peasants comes to the Smolny, wanting to file a petition. "We have even started eating grass like horses," says one peasant. "Soon we will start neighing like horses!" "Come now! Don't worry!" says Lenin reassuringly. "We are drinking tea with honey here, and we're not buzzing like bees, are we?"

- (Concerning the omnipresent Lenin propaganda) A kindergarten group is on a walk in a park, and they see a baby hare. These are city kids who have never seen a hare. "Do you know who this is?" asks the teacher. No one knows. "Come on, kids", says the teacher, "He's a character in many of the stories, songs and poems we are always reading." Finally one kid works out the answer, pats the hare and says reverently, "So that's what you're like, Grandpa Lenin!"

- An artist is commissioned to create a painting celebrating Soviet–Polish friendship, to be called "Lenin in Poland." When the painting is unveiled at the Kremlin, there is a gasp from the invited guests; the painting depicts Nadezhda Krupskaya (Lenin's wife) naked in bed with Leon Trotsky. One guest asks, "But this is a travesty! Where is Lenin?" To which the painter replies, "Lenin is in Poland."

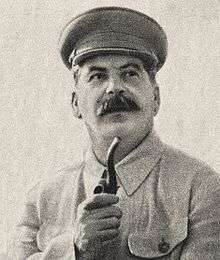

Stalin

Jokes about Stalin usually refer to his paranoia and contempt for human life. Stalin's words are typically pronounced with a heavy Georgian accent.

- Stalin attends the premiere of a Soviet comedy movie. He laughs and grins throughout the film, but after it ends he says, "Well, I liked the comedy. But that clown had a moustache just like mine. Shoot him." Everyone is speechless, until someone sheepishly suggests, "Comrade Stalin, maybe the actor shaves off his moustache?" Stalin replies, "Good idea! First shave, then shoot!"

- Stalin reads his report to the Party Congress. Suddenly someone sneezes. "Who sneezed?" Silence. "First row! On your feet! Shoot them!" They are shot, and he asks again, "Who sneezed, Comrades?" No answer. "Second row! On your feet! Shoot them!" They are shot too. "Well, who sneezed?" At last a sobbing cry resounds in the Congress Hall, "It was me! Me!" Stalin says, "Bless you, Comrade!"[7]

- A secretary is standing outside the Kremlin as Marshal Zhukov leaves a meeting with Stalin, and she hears him muttering under his breath, "Murderous moustache!". She runs in to see Stalin and breathlessly reports, "I just heard Zhukov say 'Murderous moustache'!" Stalin dismisses the secretary and sends for Zhukov, who comes back in. "Who did you have in mind with 'Murderous moustache'?" asks Stalin. "Why, Iosef Vissarionovich, Hitler, of course!" Stalin thanks him, dismisses him, and calls the secretary back. "And who did you think he was talking about?"

- An old crone had to wait for two hours to get on a bus. Bus after bus arrived full up with passengers, and she was unable to squeeze herself in as well. When she finally did manage to clamber aboard one of them, she wiped her forehead and exclaimed, "Finally, glory to God!" The driver said, "Mother, you must not say that. You must say 'Glory to comrade Stalin!'." "Excuse me, comrade," the woman replied. "I'm just a backward old woman. From now on I'll say what you told me to." After a while, she continued: "Excuse me, comrade, I am old and stupid. What shall I say if, God forbid, Stalin dies?" "Well, then you may say, 'Glory to God!'"[6]

- At a May Day parade, a very old Jew carries a placard which reads, "Thank you, comrade Stalin, for my happy childhood!" A Party representative approaches the old man. "What's that? Are you mocking our Party? Everyone can see that when you were a child, comrade Stalin hadn't yet been born!" The old man replies, "That's precisely why I'm grateful to him!"[6]

Khrushchev

Jokes about Khrushchev often relate to his attempts to reform the economy, especially to introduce maize. He was even called kukuruznik ('maizeman'). Other jokes target the crop failures resulting from his mismanagement of agriculture, his innovations in urban architecture, his confrontation with the US while importing US consumer goods, his promises to build communism in 20 years, or simply his baldness and crude manners. Unlike other Soviet leaders, in jokes Khrushchev is always harmless.

- Khrushchev visited a pig farm and was photographed there. In the newspaper office, a discussion is underway about how to caption the picture. "Comrade Khrushchev among pigs," "Comrade Khrushchev and pigs," and "Pigs surround comrade Khrushchev" are all rejected. Finally, the editor announces his decision: "Third from left – comrade Khrushchev."[6]

- Why was Khrushchev defeated? Because of the Seven "C"s: Cult of personality, Communism, China, Cuban Crisis, Corn, and Cuzka's mother (In Russian, this is the seven "K"s. To "show somebody Kuzka's mother" is a Russian idiom meaning "to give somebody a hard time". Khrushchev had used this phrase during a speech at the United Nations General Assembly, allegedly referring to the Tsar Bomba test over Novaya Zemlya.)

- Khrushchev, surrounded by his aides and bodyguards, surveys an art exhibition. "What the hell is this green circle with yellow spots all over?" he asked. His aide answered, "This painting, comrade Khrushchev, depicts our heroic peasants fighting for the fulfillment of the plan to produce two hundred million ton of grain.". "Ah-h… And what is this black triangle with red strips?". "This painting shows our heroic industrial workers in a factory.". "And what is this fat ass with ears?". "Comrade Khrushchev, this is not a painting, this is a mirror.".

Brezhnev

Leonid Brezhnev was depicted as dim-witted, suffering from dementia, always reading his speeches from paper, and prone to delusion of grandeur.

- "Leonid Ilyich is in surgery." / "His heart again?" / "No, chest expansion surgery, to make room for one more Gold Star medal." This makes reference to Brezhnev's elaborate collection of awards and medals.

- At the 1980 Olympics, Brezhnev begins his speech. "O!"—applause. "O!"—an ovation. "O!!!"—the whole audience stands up and applauds. An aide comes running to the podium and whispers, "Leonid Ilyich, those are the Olympic logo rings, you don't need to read all of them!"

- After a speech, Brezhnev confronts his speechwriter. "I asked for a 15-minute speech, but the one you gave me lasted 45 minutes!" The speechwriter replies: "I gave you three copies..."

- Somebody knocks at the door of Brezhnev's office. Brezhnev walks to the door, sets glasses on his nose, fetches a piece of paper from his pocket and reads, "Who's there?"

- "Leonid Ilyich!..." / "Come on, no formalities among comrades. Just call me 'Ilyich' ". (Note: In Soviet parlance, by itself "Ilyich" refers by default to Vladimir Lenin, and "Just call me 'Ilyich'" was a line from a well-known poem about Lenin, written by Mayakovsky.)

- Brezhnev makes a speech: "Everyone in the Politburo has dementia. Comrade Pelshe doesn't recognize himself: I say "Hello, comrade Pelshe", and he responds "Hello, Leonid Ilyich, but I'm not Pelshe." Comrade Gromyko is like a child – he's taken my rubber donkey from my desk. And during comrade Grechko's funeral – by the way, why is he absent? – nobody but me invited a lady for a dance when the music started playing."

Quite a few jokes capitalized on the cliché used in Soviet speeches of the time: "Dear Leonid Ilyich".

- The phone rings, and Brezhnev picks up the receiver (and reads from a slip of paper): "Hello, this is dear Leonid Ilyich...".

Geriatric interlude

During Brezhnev's time, the leadership of Communist Party became increasingly geriatric. By the time of his death, the median age of the Politburo was 70. Party General Secretary Leonid Brezhnev died in 1982. His successor, Yuri Andropov, died in 1984. His successor in turn, Konstantin Chernenko, died in 1985. Russians took great interest in observing the new sport at the Kremlin: hearse racing. Rabinovich said he did not have to buy tickets to the funerals, as he had a subscription to these events. As Andropov's bad health became common knowledge (he was eventually attached to a dialysis machine), several jokes made the rounds:

- "Comrade Andropov is the most turned-on man in Moscow!"

- "Why did Brezhnev go abroad, while Andropov did not? Because Brezhnev ran on batteries, but Andropov needed an outlet." (A reference to Brezhnev's pacemaker and Andropov's dialysis machine.)

- "What is the main difference between succession under the tsarist regime and under socialism?" "Under the tsarist regime, power was transferred from father to son, and under socialism – from grandfather to grandfather." (A play on words: in Russian, 'grandfather' is traditionally used in the sense of 'old man'.)

- TASS announcement: "Today, due to bad health and without regaining consciousness, Konstantin Ustinovich Chernenko took up the duties of Secretary General". (The first element in the sentence is the customary form of words at the beginning of state leaders' obituaries.)

- Another TASS announcement: "Dear comrades, of course you're going to laugh, but the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, and the entire Soviet nation, has again suffered a great loss." The phrase "of course you're going to laugh" (вы, конечно, будете смеяться) is a staple of the Odessa humor and way of speech, and the joke itself is a remake of a hundred-year-old one.[8]

- What are the new requirements for joining the Politburo? You must now be able to walk six steps without the assistance of a cane, and read three words without the assistance of paper.

Gorbachev

Mikhail Gorbachev was occasionally mocked for his poor grammar, but perestroika-era jokes usually made fun of his slogans and ineffective actions, his birth mark, Raisa Gorbachev's poking her nose everywhere, and Soviet-American relations.

- In a restaurant:

- ― Why are the meatballs cube-shaped?

- ― Perestroika! (restructuring)

- ― Why are they undercooked?

- ― Uskoreniye! (acceleration)

- ― Why have they got a bite out of them?

- ― Gospriyomka! (state approval)

- ― Why are you telling me all this so brazenly?

- ― Glasnost! (openness)

- A Soviet man is waiting in line to purchase vodka from a liquor store, but due to restrictions imposed by Gorbachev, the line is very long. The man loses his composure and screams, "I can't take this waiting in line anymore, I HATE Gorbachev, I am going to the Kremlin right now, and I am going to kill him!" After 40 minutes the man returns and elbows his way back to his place in line. The crowd begin to ask if he has succeeded in killing Gorbachev. "No, I got to the Kremlin all right, but the line to kill Gorbachev was even longer than here!".

- Baba Yaga and Koschei the Immortal are sitting by the window in the cabin on chicken legs and see Zmey Gorynych flying low, cawing "Perestroika! Uskoreniye!" Baba Yaga: "This old stupid worm! Told him not to eat communists already!"

- An American man and a Soviet man are arguing about which country is better. 'At the end of the day, I can march into the oval office, pound the President's desk and say "Mr. President I don't like the way you are running this country."', says the American. The Soviet man replies, 'I can do that too. I can march in to the Kremlin, pound the General Secretary's desk and say "Mr. Gorbachev, I don't like the way President Reagan is running his country!"'

KGB

Telling jokes about the KGB was considered to be like pulling the tail of a tiger.

- A hotel. A room for four with four strangers. Three of them soon open a bottle of vodka and proceed to get acquainted, then drunk, then noisy, singing, and telling political jokes. The fourth man desperately tries to get some sleep; finally, in frustration he surreptitiously leaves the room, goes downstairs, and asks the lady concierge to bring tea to Room 67 in ten minutes. Then he returns and joins the party. Five minutes later, he bends to a power outlet: “Comrade Major, some tea to Room 67, please.” In a few minutes, there’s a knock at the door, and in comes the lady concierge with a tea tray. The room falls silent; the party dies a sudden death, and the prankster finally gets to sleep. The next morning he wakes up alone in the room. Surprised, he runs downstairs and asks the concierge what happened to his companions. “You don’t need to know!” she answers. “B-but… but what about me?” asks the terrified fellow. “Oh, you… well… Comrade Major liked your tea gag a lot.”

- The KGB, the GIGN (or in some versions of the joke, the FBI) and the CIA are all trying to prove they are the best at catching criminals. The Secretary General of the UN decides to set them a test. He releases a rabbit into a forest, and each of them has to catch it. The CIA people go in. They place animal informants throughout the forest. They question all plant and mineral witnesses. After three months of extensive investigations, they conclude that the rabbit does not exist. The GIGN (or FBI) goes in. After two weeks with no leads they burn the forest, killing everything in it, including the rabbit, and make no apologies: the rabbit had it coming. The KGB goes in. They come out two hours later with a badly beaten bear. The bear is yelling: “Okay! Okay! I’m a rabbit! I’m a rabbit!” (A variation on this has scientists trying to discover the age of an ancient human skeleton to no avail. The KGB spends a few minutes alone with the skeleton; they come out and announce a date; the scientists find the date is true. How did the KGB find the date? The skeleton talked!)

Quite a few jokes and other humour capitalized on the fact that Soviet citizens were under KGB surveillance even when abroad:

- A quartet of violinists returns from an international competition. One of them was honored with the opportunity to play a Stradivarius violin, and cannot stop bragging about it. The violinist who came in last grunts: “What’s so special about that?” The first one thinks for a minute: “Let me put it to you this way: just imagine that you were given the chance to fire a couple of shots from Dzerzhinsky’s mauser…”

- In a prison, two inmates are comparing notes. “What did they arrest you for?” asks the first. “Was it a political or common crime?” “Of course it was political. I’m a plumber. They summoned me to the district Party committee to fix the sewage pipes. I looked and said, ‘Hey, the entire system needs to be replaced.’ So they gave me seven years.”[6]

- A frightened man came to the KGB. “My talking parrot has disappeared.” “That’s not the kind of case we handle. Go to the criminal police.” “Excuse me, of course I know that I must go to them. I am here just to tell you officially that I disagree with the parrot.”[6]

Daily Soviet life

- Q: Which is more useful – newspapers or television? A: Newspapers, of course. You can't wrap herring in a TV. (Variation: "You can't wipe your ass with a TV" – a reference to the shortage of toilet paper in USSR, which forced people to use newspapers instead.)

- We pretend to work, and they pretend to pay us! (A joke that circulated freely in factories and other places of state-run employment.)

- Five precepts of the Soviet intelligentsia (intellectuals):

- Don't think.

- If you think, then don't speak.

- If you think and speak, then don't write.

- If you think, speak and write, then don't sign.

- If you think, speak, write and sign, then don't be surprised.

- An old woman asks her granddaughter: "Granddaughter, please explain Communism to me. How will people live under it? They probably teach you all about it in school." "Of course they do, Granny. When we reach Communism, the shops will be full – there'll be butter, and meat, and sausage … you'll be able to go and buy anything you want..." "Ah!" exclaimed the old woman joyfully. "Just like under the Tsar!"[9]

- Every morning a man would come up to the newspaper stand, and buy a copy of Pravda, look at the front page and then toss it angrily into the nearby bin. The newspaper-seller was intrigued. "Excuse me," he said to the man, "Every morning you buy a copy of Pravda from me and chuck it in the bin without even unfolding it. What do you buy it for?" "I'm only interested in the front page,' replied the man. "I'm looking out for an obituary." – "But you don't get obituaries on the front page!" – "I assure you, this one will be on the front page."[10] (The US version of this joke features an anti-Franklin Delano Roosevelt newspaper buyer.)

- A regional Communist Party meeting is held to celebrate the anniversary of the Great October Socialist Revolution. The Chairman gives a speech: "Dear comrades! Let's look at the amazing achievements of our Party after the revolution. For example, Maria here, who was she before the revolution? An illiterate peasant; she had but one dress and no shoes. And now? She is an exemplary milkmaid known throughout the entire region. Or look at Ivan Andreev, he was the poorest man in this village; he had no horse, no cow, and not even an ax. And now? He is a tractor driver with two pairs of shoes! Or Trofim Semenovich Alekseev – he was a nasty hooligan, a drunk, and a dirty gadabout. Nobody would trust him with as much as a snowdrift in wintertime, as he would steal anything he could get his hands on. And now he's Secretary of the Party Committee!"[6]

Some jokes ridiculed the level of political indoctrination in the Soviet Union's education system:

- "My wife has been going to cooking school for three years." / "She must really cook well by now!" / "No, so far they've only got as far as the bit about the Twentieth CPSU Congress."

Quite a few jokes poke fun at the permanent shortages in various shops.

- A man walks into a shop and asks, "You wouldn't happen to have fish, would you?". The shop assistant replies, "You've got it wrong – ours is a butcher's shop: we wouldn't happen to have meat. You're looking for the fish shop across the road. There they wouldn't happen to have fish!"

- An American man and a Soviet man died on the same day and went to Hell together. The Devil told them: "You may choose to enter two different types of Hell: the first is the American-style one, where you can do anything you like, but only on condition of eating a bucketful of manure every day; the second is the Soviet-style hell, where you can ALSO do anything you like, but only on condition of eating TWO bucketfuls of manure a day." The American chose the American-style Hell, and the Soviet man chose the Soviet-style one. A few months later, they met again. The Soviet man asked the American: "Hi, how are you getting on?" The American said: "I'm fine, but I can't stand the bucketful of manure every day. How about you?" The Soviet man replied: "Well, I'm fine, too, except that I don't know whether we had a shortage of manure, or if somebody stole all the buckets."

A subgenre of the above-mentioned type of joke targets long sign-up queues for certain commodities, with wait times that could be counted in years rather than weeks or months.

- "Dad, can I have the car keys?" / "OK, but don't lose them. We will get the car in only seven years!"

- "I want to sign up for the waiting list for a car. How long is it?" / "Precisely ten years from today." / "Morning or evening?" / "Why, what difference does it make?" / "The plumber's due in the morning".

- An American dog, a Polish dog and a Soviet dog sit together. The American dog says 'In my country if you bark long enough, you will be heard and given some meat', the Polish dog replies 'What is "meat"?' and the Soviet dog says 'What is "bark"?'. This is a reference to the lack of free speech in the Soviet Union.

See also

References

- ↑ ir.spb.ru http://www.ir.spb.ru/naum-218.htm. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ "Hammer & tickle", Prospect Magazine, May 2006, essay by Ben Lewis on jokes in Communist countries,

- ↑ Ben Lewis (2008) "Hammer and Tickle", ISBN 0-297-85354-6 (a review online)

- ↑ A review of the Ben Lewis book

- ↑ Alexander Solzhenitsyn, Gulag Archipelago, Ch. 19, "Zeks as a Nation"

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 http://www.johndclare.net/Russ12_Jokes.htm One Hundred Russian Jokes

- ↑ Graham, Seth (2004) A Cultural Analysis of the Russo-Soviet Anekdot. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Pittsburgh.

- ↑ Валерий Смирнов, "Умер-шмумер, лишь бы был здоров!: как говорят в Одессе" , 2008, ISBN 9668788613, p. 147

- ↑ http://www.russian-jokes.com/political_jokes/communism_explained.shtml Communism Explained

- ↑ http://www.russian-jokes.com/political_jokes/why_do_you_buy_pravda.shtml Why do you buy Pravda?

- Tiny Revolution Russia: Twentieth Century Soviet and Russian History in Anecdotes and Jokes

- Emil Draitser, Forbidden Laughter (1980) ISBN 0-89626-045-3

- Christie Davies, Jokes and Their Relation to Society (1998) ISBN 3-11-016104-4, Chapter 5: "Stupidity and rationality: Jokes from the iron cage" (about jokes from beyond the Iron Curtain)

- Contemporary Russian Satire: A Genre Study

- Laughter through tears: Underground wit, humor, and satire in the Soviet Russian Empire

- Is That You Laughing Comrade? the World's Best Russian (Underground Jokes)

- Rodger Swearingen, What's so funny, comrade? (1961) ASIN B0007DX2Z0

- Dora Shturman, Sergei Tiktin (1985) "Sovetskii Soiuz v zerkale politicheskogo anekdota" ("Soviet Union in the Mirror of the Political Joke"), Overseas Publications Interchange Ltd., ISBN 0-903868-62-8 (Russian)

External links

- 1001 Soviet political anecdotes in Wikisource (Russian)

- A collection of Russian jokes (Russian)

- Political jokes about Tzars (Russian)