Samarra

Coordinates: 34°11′54″N 43°52′27″E / 34.19833°N 43.87417°E

| Sāmarrā' سامَرّاء | |

|---|---|

| City | |

|

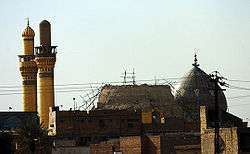

The Shrine of two Shiʿi Imams in Samarra. | |

Sāmarrā' | |

| Coordinates: 34°11′54″N 43°52′27″E / 34.19833°N 43.87417°E | |

| Country |

|

| Governorate | Saladin Governorate |

| Population (2003 est) | |

| • Total | 348,700 |

| Official name | Samarra Archaeological City |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | ii, iii, iv |

| Designated | 2007 (33rd session) |

| Reference no. | 276 |

| State Party |

|

| Region | Arab States |

| Endangered | 2007–present |

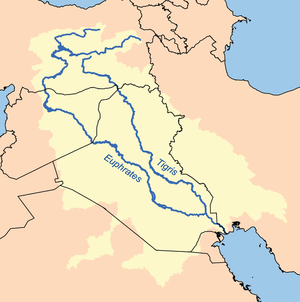

Sāmarrā (Arabic: سامَرّاء) is a city in Iraq. It stands on the east bank of the Tigris in the Saladin Governorate, 125 kilometers (78 mi) north of Baghdad. In 2003 the city had an estimated population of 348,700. Samarra was once in the "Sunni Triangle" of violence during the Iraqi Civil War of 2006-2007

In the medieval times, Samarra was the capital of the Abbasid Caliphate and the only remaining Islamic capital that retains its original plan, architecture and artistic relics.[1] In 2007, UNESCO named Samarra one of its World Heritage Sites.[2]

History

Ancient Samarra

The remains of prehistoric Samarra were first excavated between 1911 and 1914 by the German archaeologist Ernst Herzfeld. Samarra became the type site for the Samarra culture. Since 1946, the notebooks, letters, unpublished excavation reports and photographs have been in the Freer Gallery of Art in Washington, DC.

The civilization flourished alongside the Ubaid period, as one of the first town states in the Near East. It lasted from 5,500 BCE and eventually collapsed in 3,900 BCE.

A city of Sur-marrati (refounded by Sennacherib in 690 BC according to a stele in the Walters Art Museum) is insecurely identified with a fortified Assyrian site of Assyrian at al-Huwaysh on the Tigris opposite modern Samarra. The State Archives of Assyria Online identifies Surimarrat as the modern site of Samarra.[4]

Ancient place names for Samarra noted by the Samarra Archaeological Survey are Greek Souma (Ptolemy V.19, Zosimus III, 30), Latin Sumere, a fort mentioned during the retreat of the army of Julian in 363 AD (Ammianus Marcellinus XXV, 6, 4), and Syriac Sumra (Hoffmann, Auszüge, 188; Michael the Syrian, III, 88), described as a village.

The possibility of a larger population was offered by the opening of the Qatul al-Kisrawi, the northern extension of the Nahrawan Canal which drew water from the Tigris in the region of Samarra, attributed by Yaqut al-Hamawi (Muʿjam, see under "Qatul") to Khosrau I (531–578). To celebrate the completion of this project, a commemorative tower (modern Burj al-Qa'im) was built at the southern inlet south of Samarra, and a palace with a "paradise" or walled hunting park was constructed at the northern inlet (modern Nahr ar-Rasasi) near ad-Dawr. A supplementary canal, the Qatul Abi al-Jund, excavated by the Abbasid Caliph Harun al-Rashid, was commemorated by a planned city laid out in the form of a regular octagon (modern Husn al-Qadisiyya), called al-Mubarak and abandoned unfinished in 796.

Abbasid capital

In 836 the Abbasid Caliph Al-Mu'tasim founded a new capital at the banks of the Tigris. Here he built extensive palace complexes surrounded by garrison settlements for his guards, mostly drawn from Central Asia and Iran (most famously the Turks, as well as the Khurasani Ishtakhaniyya, Faraghina and Ushrusaniyya regiments) or North Africa (like the Maghariba). Although quite often called Mamluk slave soldiers, their status was quite elevated; some of their commanders bore Sogdian titles of nobility.[5]

The city was further developed under Caliph al-Mutawakkil, who sponsored the construction of lavish palace complexes, such as al-Mutawakkiliyya, and the Great Mosque of Samarra with its famous spiral minaret or Malwiya, built in 847. For his son al-Mu'tazz he built the large palace Bulkuwara.

Samarra remained the residence of the caliph until 892, when al-Mu'tadid eventually returned to Baghdad. The city declined but maintained a mint until the early 10th century.

The Nestorian patriarch Sargis (860–72) moved the patriarchal seat of the Church of the East from Baghdad to Samarra, and one or two of his immediate successors may also have sat in Samarra so as to be close to the seat of power.[6]

After the collapse of the Abbasid empire in about 940 Samarra was abandoned. Its population returned to Baghdad and the city rapidly declined. Its field of ruins is the only world metropolis of late antiquity which is available for serious archaeology.

Islamic significance

The city is also home to al-Askari Shrine, containing the mausolea of the Ali al-Hadi and Hasan al-Askari, the tenth and eleventh Shiʿi Imams, respectively, as well as the place from where Muhammad al-Mahdi, known as the "Hidden Imam", went into The Occultation in the belief of the Twelvers. This has made it an important pilgrimage centre for the Twelvers. In addition, Hakimah and Narjis, female relatives of the Muhammad and the Imams, held in high esteem by Muslims, are buried there, making this mosque one of the most significant sites of worship.

The Sunnis also pray in the mosques similar to the Shi'a; they also conduct pilgrimages to these sites, coming as far as from South and Southeast Asia, but they do not believe this to be obligatory, but rather an affair providing spiritual blessings.

Modern era

.jpg)

In the eighteenth century, one of the most bloody battles of the 1730–35 Ottoman–Persian War, the Battle of Samarra, took place, where over 50,000 Turks and Persians became casualties. The engagement decided the fate of Ottoman Iraq and kept it under Istanbul's suzerainty until the first world war.

During the 20th century, Samarra gained new importance when a permanent lake, Lake Tharthar, was created through the construction of the Samarra Barrage, which was built in order to prevent the frequent flooding of Baghdad. Many local people were displaced by the dam, resulting in an increase in Samarra's population.

Samarra is a key city in Saladin Governorate, a major part of the so-called Sunni Triangle where insurgents were active during the Iraq War.

Though Samarra is famous for its Shi'i holy sites, including the tombs of several Shi'i Imams, the town was traditionally and until very recently, dominated by Sunni Arabs. Tensions arose between Sunnis and the Shi'a during the Iraq War. On February 22, 2006, the golden dome of the al-Askari Mosque was bombed, setting off a period of rioting and reprisal attacks across the country which claimed hundreds of lives. No organization claimed responsibility for the bombing. On June 13, 2007, insurgents attacked the mosque again and destroyed the two minarets that flanked the dome's ruins.[7] On July 12, 2007, the clock tower was blown up. No fatalities were reported. Shiʿi cleric Muqtada al-Sadr called for peaceful demonstrations and three days of mourning.[8] He stated that he believed no Sunni Arab could have been behind the attack, though according to the New York Times the attackers were likely Sunnis linked to Al-Qaeda.[9] The mosque compound and minarets had been closed since the 2006 bombing. An indefinite curfew was placed on the city by the Iraqi police.[10][11]

Ever since the end of Iraqi civil war in 2007, the Shia population of the holy city has increased exponentially. However, violence has continued, with bombings taking place in 2011 and 2013. In June 2014, the city was attacked by the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) as part of the Northern Iraq offensive. ISIL forces captured the municipality building and university, but were later repulsed.[12]

Samarra in popular culture

The metaphor of "Having an appointment in Samarra", signifying death, is a literary reference to an ancient Babylonian myth,[13] transcribed by W. Somerset Maugham,[14] in which Death is both the narrator and a central character. The story, "The Appointment in Samarra", subsequently formed the germ of a popular novel[15] by John O'Hara. The original story was re-told in verse by F. L. Lucas in his poem 'The Destined Hour' in From Many Times and Lands (1953).[16]

References

- ↑ UNESCO, Samarra Archaeological City, http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/276

- ↑ "Unesco names World Heritage sites". BBC News. 2007-06-28. Retrieved 2010-05-23.

- ↑ Stanley A. Freed, Research Pitfalls as a Result of the Restoration of Museum Specimens, Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, Volume 376, The Research Potential of Anthropological Museum Collections pages 229–245, December 1981.

- ↑ SAAO

- ↑ Babaie, Sussan (2004). Slaves of the Shah. New York: I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd. pp. 4–5. ISBN 1 86064 721 9.

- ↑ Mari, 80–1 (Arabic), 71–2 (Latin)

- ↑ Thomas E. Ricks (6 January 2010). The Gamble: General Petraeus and the American Military Adventure in Iraq. Penguin Publishing Group. p. 228. ISBN 978-1-101-19206-1.

- ↑ "Explosion Topples Minarets At Iraqi Shi'ite Shrine". RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty. 2007-06-13. Retrieved 2015-08-22.

- ↑ John F. Burns; Jon Elsen (2007-06-14). "Several Mosques Attacked, but Iraq Is Mostly Calm - New York Times". nytimes.com. Retrieved 2015-08-22.

- ↑ Qassim Abdul-Zahra (June 13, 2007). "Iraqi police say famous shrine attacked". Associated Press.

- ↑ "Blast hits key Iraq Shia shrine". BBC. 2007-06-13. Retrieved 2012-04-21.

- ↑ Hassan, Ghazwan (5 June 2014). "Iraq dislodges insurgents from city of Samarra with airstrikes". Reuters. Retrieved 27 June 2014.

- ↑ This is recorded in the Babylonian Talmud, Sukkah 53a.

- ↑ "The Appointment in Samarra" (as retold by W. Somerset Maugham [1933])

- ↑ John O'Hara, Appointment in Samarra, Harcourt, Brace & Co., 1934. ISBN 0-375-71920-2

- ↑ Lucas, F. L., ‘The Destined Hour’ in From Many Times and Lands (London, 1953); reprinted in Every Poem Tells a Story: A Collection of Stories in Verse, ed. Raymond Wilson (London, 1988; ISBN 0-670-82086-5 / 0-670-82086-5)

Selected Bibliography

- De la Vaissière, Étienne (2007): Samarcande et Samarra. Élites d’Asie central dans l’empire abbaside (Studia Iranica, Cahier 35), Paris.

- Gordon, Matthew S. (2001): The Breaking of a Thousand Swords. A History of the Turkish Military of Samarra (A.H. 200-275, 815-889 C.E.), Albany.

- Northedge, Alastair (2005): The historical topography of Samarra, London.

- Robinson, Chase (ed.) (2001): A Medieval Islamic City Reconsidered: An Interdisciplinary Approach to Samarra (Oxford Studies in Islamic Art 14). Oxford.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Samarra. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Samarra. |

- Ernst Herzfeld Papers, Series 7: Records of Samarra Expeditions, 1906-1945 Smithsonian Institution, Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery Archives, Washington, DC

- Ernst Herzfeld Papers, Series 7: Records of Samarra Expeditions, 1906-1945 Collections Search Center, S.I.R.I.S., Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC

- Iraq Image - Samarra Satellite Observation

- Samarra Archaeological Survey

- The Appointment in Samarra

- Destruction of Askari Mosque

- Samarra on Google Earth