Schweipolt Fiol

Schweipolt Fiol (also Sebald Vehl or Veyl; born approximately in 1460? - died 1525 or 1526) was a German-born 15th century pioneer of printing in Eastern Europe, founder of the Slavic Cyrillic script typography. The exact date of his birth and death are unknown.

Fiol spent a considerable part of his life in Poland, particularly Kraków, the capital of the Polish Kingdom at the time. The city was famous for its university. The burgeoning of the arts and sciences contributed to the early emergence of book printing here: as early as 1473-1477 there was a print shop in Kraków, which published numerous theological works.

Fiol was a multifaceted and gifted man: he worked as a mining engineer and jeweler, and then took over a print shop. It is this print shop, owned by Fiol, which first published in Cyrillic such Eastern Slavic religious books as Horologion, Octoechos, and the two Triodi.

The very first book printed in Cyrillic script, Oktoikh (Octoechos), was published by Fiol in 1491 in Kraków.[1]

Biography

The exact date of his birth is unknown. He was born in Neustadt an der Aisch in Franconia. Then he moved to Kraków in 1479 and was soon enrolled in a department of Goldsmiths. He worked as a gold embroiderer (German: perlenhaftir).[2][3]

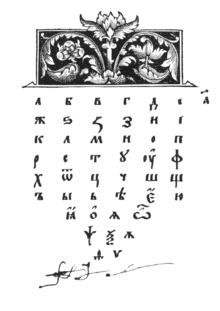

On March 9, 1489, the King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania Casimir issued Fiol the privilege to the invention of a machine for pumping water from mines.[3] The invention has been under interest of a wealthy merchant and banker John Thurzo (1437-1508), who owned a number of mines, including the lead mines in Olkusz. Subsequently Thurzo, with the Kraków patrician Jan Teshnarom had sponsored Fiol's printing house. To start printing it was necessary to cut out the appropriate Cyrillic script.

On October 26, 1489 Fiol signed a contract with Karbesom Jacob, who pledged to "engrave letters and adjust font Russian." At the same time, he went to Nuremberg, probably in order to make punches and matrices for the subsequent embossing.

Documentary evidence about Fiol referred to on September 18, 1490: Fiol accused Johann and Nikolaus Svedlera of Neuburg of the theft of paper kept in his workshop in Kraków. Later, in turn, they filed for Fiola to court for libel. However, evidences was not provided by Fiol, but he said he saw the theft with his own eyes. The court's decision in this case was unknown.

The final version of the Cyrillic script and some of the letters commissioned by Fiol was cut out by student of Kraków University, Rudolf Borsdorf from Braunschweig who quickly supplied Fiol with 230 completely finished and adjusted letters and superscript icons (Ludolfus Ludolfi de Brunszwyczk).[3]

We also know that Rudolph pledged not to make such fonts for anyone else, even for himself, and not teach how to make them, as Fiol did not want to let someone else print Church Slavonic books.[4]

Famous German poet and humanist Conrad Celtis, lived in the years 1489-1491 in Kraków, and in his works, supported Fiols' publishing.[5]

In July 1491 Fiol pleaded with Mr. Otto for money. On August 1, 1491 the book printer was convicted and sent to prison on November 21. Fiol was released with a bail of 1000 Hungarian florins, provided by his patrons.[5]

On March 22, 1492 Fiol was convicted of heretical statements. On March 27, 1492 the master was justified in ecclesiastical court, perhaps due to the intercession of John Thurzo. On January 13, 1492 the Archbishop of Gniezno, Jan Thurzo had recommended him to refrain from sharing and printing Russian books.[5]

From 1502 Fiol lived in Reichenstein, and later moved to the town of Levoca, where he was mining. In his last years he lived in Kraków, living on a pension granted to him by the Thurzo family. Schweipolt Fiol died at the end of 1525 or early 1526.[5]

Fiol was married to Margaret, the eldest daughter of a wealthy citizen of Kraków, Nicholas Lyubchitsa. Since Margaret is not mentioned in the will from May 7, 1525, we can assume that either she died before or at this point, they were divorced.[4]

Printing in Poland

Printing in Poland began in the late 15th century, when following the creation of the Gutenberg Bible in 1455, printers from Western Europe spread the new craft abroad.

The Polish capital at the time was in Kraków, where scholars, artists and merchants from Western Europe had already been present. Other cities which were part of the Polish kingdom followed later. Cities of northern Polish province of Royal Prussia,[6] like the Hanseatic League city of Danzig (Gdańsk), had established printing houses early on.

The first printing shop was possibly opened in Kraków by Augsburg-based Günther Zainer in 1465. In 1491, Schweipolt Fiol printed the first book in Cyrillic script. The next recorded printing shop was a Dutch one known by the name Typographus Sermonum Papae Leonis I. that might have been established in 1473 on Polish territory, but its exact location has yet to be determined.[7]

The oldest known print from Poland is considered to be the Almanach cracoviense ad annum 1474 (Cracovian Almanac for the Year 1474) which is a single-sheet astronomical wall calendar for the year 1474 printed and published in 1473 by Kasper Straube.[8] The only surviving copy of the Almanach cracoviense measures 37 cm by 26.2 cm, and is in the collection of the Jagiellonian University.

The first print written in Polish language is believed to be Hortulus Animae polonice, a Polish version of Hortulus Animae written by Biernat of Lublin, printed and published in 1513 by Florian Ungler in Kraków. The last known copy was lost during World War II.

One of the first commercial printers in Poland is considered to be Johann Haller who worked in Kraków in the early 16th century (since 1505) who in 1509 printed Nicolaus Copernicus's Theophilacti Scolastici Simocatti Epistole morales, rurales at amatoriae, interpretatione latina.[8]

Other well known early printers in Poland were:

- Hieronymus Vietor from Silesia who worked in Vienna and Kraków

- Printers from the Szafenberg family

- Florian Ungler

In the late 16th century there were 7 printing shops in Kraków, and in 1610 ten printing shops. A decline started in around 1615 leaving only three secular printing shops in 1650, accompanied by a few ecclesial ones.

Only one printing shop is recorded in Warszawa in 1707, owned by the Piarists. This situation improved during the realm of the last Polish king, Stanisław August Poniatowski, which marked a political and cultural revival in Poland. Unfortunately his attempts to reform the state led to the Partitions of Poland carried out by Prussia, Austria and Russia.

Printing technology

The world's first movable type printing technology was invented and developed in China by the Han Chinese printer Bi Sheng between the years 1041 and 1048. In the West, the invention of an improved movable type mechanical printing technology in Europe is credited to the German printer Johannes Gutenberg in 1450.[9]

The exact date of Gutenberg's press is debated based on existing screw presses. Gutenberg, a goldsmith by profession, developed a printing system by both adapting existing technologies and making inventions of his own. His newly devised hand mould made possible the rapid creation of metal movable type in large quantities Johannes Gutenberg's work on the printing press began in approximately 1436 when he partnered with Andreas Dritzehn—a man he had previously instructed in gem-cutting—and Andreas Heilmann, owner of a paper mill.[10] However, it was not until a 1439 lawsuit against Gutenberg that an official record exists; witnesses' testimony discussed Gutenberg's types, an inventory of metals (including lead), and his type molds.[10]

Having previously worked as a professional goldsmith, Gutenberg made skillful use of the knowledge of metals he had learned as a craftsman. He was the first to make type from an alloy of lead, tin, and antimony, which was critical for producing durable type that produced high-quality printed books and proved to be much better suited for printing than all other known materials. To create these lead types, Gutenberg used what is considered one of his most ingenious inventions,[10][38] a special matrix enabling the quick and precise molding of new type blocks from a uniform template. His type case is estimated to have contained around 290 separate letter boxes, most of which were required for special characters, ligatures, punctuation marks, etc.[11]

Gutenberg is also credited with the introduction of an oil-based ink which was more durable than the previously used water-based inks. As printing material he used both paper and vellum (high-quality parchment). In the Gutenberg Bible, Gutenberg made a trial of coloured printing for a few of the page headings, present only in some copies.[12]

A later work, the Mainz Psalter of 1453, presumably designed by Gutenberg but published under the imprint of his successors Johann Fust and Peter Schöffer, had elaborate red and blue printed initials.[12]

Publishing activities

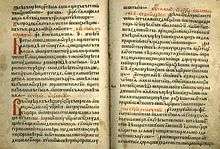

It happened that the Eastern Slavic Cyrillic printing house was founded not on the territory of one of Eastern Slavic countries, and in the capital and the largest economic center of the then Kingdom of Poland - Kraków, which at that time was home to many Ukrainian and Belarusians. There at the end of the 15th century, came the first four books printed in Cyrillic Church Slavonic. Two of them - the Book of Hours and Osmoglasnik (Octoechos) - are marked on the end-of-print in Crakow in 1491 by Schweipolt Fiol. Thus, the printed script Lenten Triodion (in one of its copies, it is not output) and Pentecostarion (the page with the symbol names Fiol is preserved only in the copy that was recently discovered in the city of Brașov).[4]

Scientists assume that customers, who ordered printing liturgical texts, have been associated with the Kyiv Metropolis or one of its dioceses. Experts believe that the model for the (very modest) designs of these publications were Slavic manuscripts, particularly from Carpathian churches.[13]

Books

In total in Fiol's printing house in Kraków, he published four editions of Church Slavonic books:

- "Octoechos" (Osmoglasnik, 1491)

- "Book of Hours" (1491)

- "Lenten Triodion" (1492—1493)

- "Pentecostarion" (unknown)

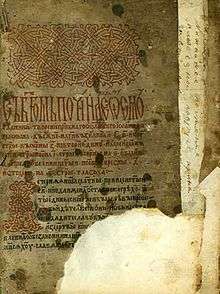

"Octoechos" and "Book of Hours" has the following colophon, in which the text is typed without spaces, making it difficult to understand and produced several variants of its interpretation. For example, this lack of clarity has allowed the Polish literary critic K. Estrayher to say that publishers could be two people: the Slav Sviatopolk and a German, a native franc.[14]

Once documents found to reside in 1478-1499 in Kraków, Fiol, who called himself franc, this reading has lost all meaning. In the Ukrainian historiography, still Fiol called Sviatopolk of Lemko, of which there is no documentary evidence.[4]

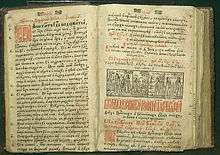

"Octoechos" printed in the format in folio, made in the technique of two-color printing, and is made up of twenty two[15] 8-sheet notebooks. The last 3 sheets are blank, with 172 total pages. Some of the pages are decorated with complex patterns, in the beginning of each chapter, capital letters are painted with vermilion, decorated with a modest ornament. On the second page of the book before the start of the text displayed under a braided headband is a braided initial. In addition, incunabula contains 12 lines and simple tie in drawing, small in terms of size, the initials of pawn shops.[16]

In "Pentecostarion" there is no colophon, but there is typographical Fiol mark. Anonymous printed in the same font of "Lenten Triodion." 28 preserved copies of "Pentecostarion", of which at least 4 are complete. "Pentecostarion" consists of 366 pages, the most complete specimen was found in October 1971 in the church of St. Nicholas Schei and is at the Museum of Romanian culture in Brasov (Romania), only 21 have survived.[16]

References

- ↑ Treasures of the National Library - Moscow, retrieved on November 3, 2007.

- ↑ Мастера perlenhaftir вышивали ткани золотом и серебром и украшали их драгоценными камнями

- 1 2 3 Галенчанка Г. Фіёль // Вялікае Княства Літоўскае. — Т. 2: Кадэцкі корпус — Яцкевіч. — Мінск: Беларуская Энцыклапедыя імя П.Броўкі, 2005. — 788 с.: іл. — с. 702. ISBN 985-11-0378-0. (Belarusian)

- 1 2 3 4 Ісаєвич Я. Початки кириличного друкарства // Українське книговидання: витоки, розвиток, проблеми. — Львів: Інститут українознавства ім. І. Крип’якевича НАН України, 2002. — 520 с. — с. 88-91 (Belarusian)

- 1 2 3 4 American Slavic and East European Review, Vol. 18, No. 4, Dec., 1959, Association for Slavic, East European, and Eurasian Studies ISSN 1049-7544 (Belarusian)

- ↑ Daniel Stone,A History of East Central Europe, University of Washington Press, 2001, p. 30, ISBN 0-295-98093-1 Google Books

- ↑ [Wieslaw Wydra, "Die ersten in polnischer Sprache gedruckten Texte, 1475–1520", Gutenberg-Jahrbuch, Vol. 62 (1987), pp.88–94 (88)]

- 1 2 Davies, Norman (2005). "Anjou: The Hungarian Connection". God's Playground: A History of Poland in Two Volumes. Vol. I. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 118. ISBN 0-19-925339-0.

- ↑ The invention of typography—Gutenberg (1450?)

- 1 2 3 [Meggs, Philip B. A History of Graphic Design. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 1998. (pp 58–69) ISBN 0-471-29198-6](Belarusian)

- ↑ [Mahnke, Helmut (2009), Der kunstreiche Johannes Gutenberg und die Frühzeit der Druckkunst, Norderstedt: Books on Demand, ISBN 978-3-8370-5041-7]

- 1 2 [Kapr, Albert (1996), Johannes Gutenberg. The Man and his Invention, Aldershot: Scolar, ISBN 1-85928-114-1](Belarusian)

- ↑ Щоденна всеукраїнська газета «День», Врятований із забуттяIван Огієнко та Фіоль Швайпольт, 30 листопада, 2007

- ↑ Estreicher K. Gunter Zainer i Świętopołk Fioł. — Warszawa, 1867. — S. 52-56. (odb. z «Biblioteka Warszawka»)

- ↑ Except for the last twenty-second notebook.

- 1 2 Первенец славянского книгопечатания - Октоих 1491 г. Книжные памятники Архангельского Севера(Belarusian)

- Szwejkowska H., Książka drukowana XV - XVIII wieku. Zarys historyczny, Wyd. 3 popr., PWN Wrocław ; Warszawa 1980.

- Norman Davies, God's Playground: A History of Poland: in Two Volumes, S. 118

- Про обставини видання кириличних першодруків див.: Грушевський М. Історія української літератури, т. 5, с. 129-138; Немировский Е.Л. Начало славянского книгопечатания, Москва 1971.

Literature

- Немировский Е. Л. Начало славянского книгопечатания. — М., 1971.

- Немировский Е. Л. Описание изданий типографии Швайпольта Фиоля // Описание старопечатных изданий кирилловского шрифта. — М., 1979.

- Немировский Е. Л. Начало славянского книгопечатания кирилловским шрифтом // Книга: исследования и материалы. — М., 1991. — Сб. 63.

- Wiener allgemeine Literatur-Zeitung, Dritter Jahrgang, 1815