Science and technology in Hungary

Science and technology in Hungary has a long history.

Science

Early education history

The "Berg-Schola", the world's first institute of technology, was founded in Selmecbánya, Kingdom of Hungary[1] (today Banská Štiavnica, Slovakia), in 1735. Its legal successor is the University of Miskolc in Hungary.

BME University is considered the world's oldest institute of technology which has university rank and structure. It was the first institute in Europe to train engineers at university level.[2] The legal predecessor of the university was founded in 1782 by Emperor Joseph II, and was named Latin: Institutum Geometrico-Hydrotechnicum ("Institute of Geometry and Hydrotechnics").

Scientists and inventors

Important names in the 18th century are Maximilian Hell (astronomer), János Sajnovics (linguist), Matthias Bel (polyhistor), Samuel Mikoviny (engineer) and Wolfgang von Kempelen (polyhistor and co-founder of comparative linguistics). Ányos Jedlik physicist and engineer invented the first electric motor(1828), the dynamo, the self-excitation, the impulse generator, and the cascade connection. Important name in 19th century physics is Joseph Petzval,one of the founders of modern optics. The invention of the transformer (by Ottó Bláthy Miksa Déri and Károly Zipernowsky), the AC electricity meter and the electricity distribution systems with parallel-connected power sources decided the future of electrification in the War of Currents, which resulted in the global triumph of alternate current systems over the former direct current systems. Roland von Eötvös discovered the weak equivalence principle (one of the cornerstones in Einsteinian relativity). Rado von Kövesligethy discovered laws of black body radiation before Planck and Wien.[3][4] Hungary is famous for its excellent mathematics education which has trained numerous outstanding scientists. Famous Hungarian mathematicians include father Farkas Bolyai and son János Bolyai, designer of modern geometry (non-Euclidean geometry) 1820–1823. János Bolyai is together with John von Neumann considered as the greatest Hungarian mathematician ever. The most prestigious Hungarian scientific award is named in honor of János Bolyai. Paul Erdős, famed for publishing in over forty languages and whose Erdős numbers are still tracked;[5] and John von Neumann, Quantum Theory, Game theory a pioneer of digital computing and the key mathematician in the Manhattan Project. Many Hungarian scientists, including Zoltán Bay, Victor Szebehely (gave a practical solution to the three-body problem, Newton solved the two-body problem), Mária Telkes, Imre Izsak, Erdős, von Neumann, Leó Szilárd, Eugene Wigner and Edward Teller emigrated to the US. The other cause of scientist emigration was the Treaty of Trianon, by which Hungary, diminished by the treaty, became unable to support large-scale, costly scientific research; therefore some Hungarian scientists made valuable contributions in the United States. Thirteen Hungarian or Hungarian-born scientists received the Nobel Prize: von Lenárd, Bárány, Zsigmondy, von Szent-Györgyi, de Hevesy, von Békésy, Wigner, Gábor, Polányi, Oláh, Harsányi, and Herskó. All emigrated, mostly because of persecution of communist and/or fascist regimes. Names in psychology are János Selye founder of Stress-theory and Csikszentmihalyi founder of Flow- theory. Tamás Roska is co-inventor of CNN (Cellular neural network) Some highly actual internationally well-known figures of today include: mathematician László Lovász, physicist Albert-László Barabási, physicist Ferenc Krausz, biochemist Árpád Pusztai and the highly controversial former NASA-physicist Ferenc Miskolczi, who denies the green-house effect.[6] According to Science Watch: In Hadron research Hungary has most citations per paper in the world.[7] In 2011 neuroscientists György Buzsáki, Tamás Freund and Péter Somogyi were awarded one million Euro with The Brain Prize ("Danish Nobel Prize")" for ".. brain circuits involved in memory..."[8] After the fall of the communist dictatorship (1989), a new scientific prize, Bolyai János alkotói díj, has been established (1997), politically unbiased and of the highest international standard.

Hungarian inventions

- The English word "coach" came from the Hungarian kocsi ("wagon from Kocs" referring to the village in Hungary where coaches were first made).[9][10]

- Wolfgang von Kempelen invented a manually operated speaking machine in 1769.

- János Irinyi invented the noiseless match.

- In 1827 Ányos Jedlik invented the electric motor. He created the first device to contain the three main components of practical direct current motors: the stator, rotor and commutator. He built the first generator which used, instead of permanent magnets, two electromagnets opposite to each other to induce the magnetic field around the rotor.[1][2] It was also the discovery of the principle of "dynamo self-excitation"

- David Schwarz invented and designed the first flyable rigid airship (aluminium-made). Later, he sold his patent for German Graf Zeppelin, who built the so-called Zeppelin airship.

- Donát Bánki and János Csonka invented the Carburetor.

- Ottó Bláthy, Miksa Déri and Károly Zipernowsky invented the modern transformer in 1885.[11][11]

- Ottó Bláthy invented the Turbogenerator and Wattmeter.

- Kálmán Kandó invented the Three-phase Alternating Current Electric locomotive, and was a pioneer in the development of electric railway traction.

- Tivadar Puskás invented the Telephone Exchange.

- Dezső Korda invented the Rotating Capacitor (Tuning Capacitor).

- József Galamb was the inventor of many parts of the Ford Model T and co-developer of the assembly line

- Sándor Just invented the Tungsten electric bulb (1904)

- Imre Bródy invented the krypton electric bulb.

- Loránd Eötvös: weak equivalence principle and surface tension

- Kálmán Tihanyi: Invented and described the "charge-storage" physical phenomena, a pioneer in developing Electronic Television and camera-tube (1926) and invented the Plasma TV (1936) and Infrared camera (1929).

- József Mihályi was co-designer or designer and inventor for KODAK the following cameras: Kodak Ekstra, Kodak Medalist, Kodak Super Six-20[12] and Kodak Bantam Special.[13]

- Béla Barényi designed the Volkswagen Beetle and is the father of passive safety in automobiles.

- Ervin Kováts invented the concept of Kovats retention index, a concept used in gas chromatography

- Csaba Horváth constructed the first high performance liquid chromatograph

- Ferenc Anisits created the modern diesel engine.

- Albert Szent-Györgyi discovered Vitamin C and created the first artificial vitamin. (Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1937)

- Theodore Kármán - Mathematical tools to study fluid flow and mathematical background of supersonic flight and inventor of swept-back wings, "father of Supersonic Flight"

- Albert Fonó invented the ramjet propulsion

- György Jendrassik invented the Turboprop propulsion

- Leó Szilárd: hypothesized the nuclear chain reaction (therefore he was the first who realized the feasibility of an atomic bomb), patented the Nuclear reactor, invented the Electron microscope and the linear accelerator (the first particle accelerator) and later invented the cyclotron[14]

- Tamás Péter Bródy invented the active-matrix thin film transistor technology which underpins the LCD and OLED displays commonly used today.

- Dennis Gabor invented the Holography (Nobel Prize in Physics in 1971)

- László Bíró invented ballpoint pen

- Edward Teller hypothesized the thermonuclear fusion and the theory of the hydrogen bomb

- John Kemeny developed the BASIC programming language with Thomas E. Kurtz

- Ferenc Pavlics was one of two co-developers of NASA Apollo Lunar rover

- Antal Bejczy developed Mars Rover Sojourner

- Ernő Rubik invented the so-called Rubik's Cube

- ArchiCAD, 3-D software was developed by Bojár (1987)

- Charles Simonyi was chief-architect at Microsoft and oversaw the creation of Microsoft's flagship Office suite of applications.[15][16]

- Gömböc, a new geometrical body, was invented in 2006 by Hungarian scientists Gábor Domokos and Péter Várkonyi

- Endre Mester invented the Low level laser therapy or "light therapy"

- Prezi, a web-based presentation application and storytelling tool, developed by Adam Somlai-Fischer and Peter Halacsy in 2007.

- Áron Losonczy invented the LiTraCon, a Translucent Concrete building material.

- Dániel Rátai invented the three-dimensional monitor: Leonar3Do.[17]

- The three-dimensional scanner microscope 3D Alba (international patent in 2007) was developed by Katona Gergely and Rózsa Balázs[18]

In August 1939, Szilárd approached his old friend and collaborator Albert Einstein and convinced him to sign the Einstein–Szilárd letter, lending the weight of Einstein's fame to the proposal. The letter led directly to the establishment of research into nuclear fission by the U.S. government and ultimately to the creation of the Manhattan Project. Szilárd, with Enrico Fermi, patented the nuclear reactor).

Technology

Early milestones in technology and infrastructure (1700–1918)

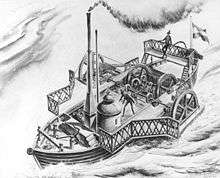

The first steam engine of continental Europe was built in Újbánya - Köngisberg, Kingdom of Hungary (Today Nová Baňa Slovakia) in 1722. It was a Newcomen type engine, it served on pumping water from mines.[19][20][21][22]

Railways

The first Hungarian steam-locomotive railway line was opened on 15 July 1846, between Pest and Vác.[26] By 1910, the total length of the rail networks of Hungarian Kingdom had reached 22,869 km (14,210 mi); the Hungarian network linked more than 1,490 settlements. This has ranked Hungarian railways as the sixth-most dense in the world (ahead of countries as Germany or France).[27]

Locomotive engine and railway vehicle manufacturers before World War One (engines and wagons, bridge and iron structures) were the MÁVAG company in Budapest (steam engines and wagons) and the Ganz company in Budapest (steam engines, wagons, the production of electric locomotives and electric trams started from 1894).[28] and the RÁBA Company in Győr.

The Ganz Works identified the significance of induction motors and synchronous motors commissioned Kálmán Kandó (1869–1931) to develop it. In 1894, Kálmán Kandó developed high-voltage three-phase AC motors and generators for electric locomotives. The first-ever electric rail vehicle manufactured by Ganz Works was a 6 HP pit locomotive with direct current traction system. The first Ganz made asynchronous rail vehicles (altogether 2 pieces) were supplied in 1898 to Évian-les-Bains (Switzerland), with a 37-horsepower (28 kW), asynchronous-traction system. The Ganz Works won the tender of electrification of railway of Valtellina Railways in Italy in 1897. Italian railways were the first in the world to introduce electric traction for the entire length of a main line, rather than just a short stretch. The 106-kilometre (66 mi) Valtellina line was opened on 4 September 1902, designed by Kandó and a team from the Ganz works.[29] The electrical system was three-phase at 3 kV 15 Hz. The voltage was significantly higher than used earlier, and it required new designs for electric motors and switching devices.[30][31] In 1918,[32] Kandó invented and developed the rotary phase converter, enabling electric locomotives to use three-phase motors whilst supplied via a single overhead wire, carrying the simple industrial frequency (50 Hz) single phase AC of the high voltage national networks.[33]

Electrified tramways

The first electric tramway was built in Budapest in 1887, which was the first tramway in Austria-Hungary. By the turn of the 20th century, 22 Hungarian cities had electrified tramway lines in Kingdom of Hungary.

Date of electrification of tramway lines in the Kingdom of Hungary:

- Hungary: Budapest (1887); Pressburg/Pozsony/Bratislava (1895); Szabadka/Subotica, Szombathely, Miskolc (1897); Temesvár/Timișoara (1899); Sopron (1900); Szatmárnémeti/Satu Mare (1900); Nyíregyháza (1905); Nagyszeben/Sibiu (1905); Nagyvárad/Oradea (1906); Szeged (1908); Debrecen (1911); Újvidék/Novi Sad (1911); Kassa/Košice (1913); Pécs (1913)

- Croatia: Fiume (1899); Pula (1904); Opatija – Lovran (1908); Zagreb (1910); Dubrovnik (1910).[34][35][36][37]

Electrified Commuter Railway lines

- Budapest (See: BHÉV): Ráckeve line (1887), Szentendre line (1888), Gödöllő line (1888), Csepel line (1912)[38]

Underground

The Budapest metro Line 1 (originally the "Franz Joseph Underground Electric Railway Company") is the second oldest underground railway in the world[39] (the first being the London Underground's Metropolitan Line), and the first on the European mainland. It was built from 1894 to 1896 and opened in Budapest on 2 May 1896.[40] In 2002, it was listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[41]

Automotive industry

Automotive industry: Prior to World War I, the Kingdom of Hungary had four car manufacturer companies; Hungarian car production started in 1900. Automotive factories in the Kingdom of Hungary manufactured motorcycles, cars, taxicabs, trucks and buses. These were: the Ganz company[42][43] in Budapest, RÁBA Automobile[44] in Győr, MÁG (later Magomobil)[45][46] in Budapest, and MARTA (Hungarian Automobile Joint-stock Company Arad)[47] in Arad.

Aeronautical industry

The first Hungarian hydrogen filled experimental ballons were built by István Szabik and József Domin in 1784. The first Hungarian designed and produced airplane (powered by inline engine) was flew in 1909 at Rákosmező.[48] The International Air-race was organized in Budapest, Rákosmező in June 1910. The earliest Hungarian radial engine powered airplane was built in 1913. Between 1913-18, the Hungarian aircraft industry began developing. The 3 greatest: UFAG Hungarian Aircraft Factory (1914), Hungarian General Aircraft Factory (1916), Hungarian Lloyd Aircraft, Engine Factory (at Aszód (1916),[49] and Marta in Arad (1914).[50] During the WW I, fighter planes, bombers and reconnaissance planes were produced in these factories. The most important aeroengine factories were Weiss Manfred Works, GANZ Works, and Hungarian Automobile Joint-stock Company Arad.

Electrical Industry and Electronics

Power plants, generators and transformers

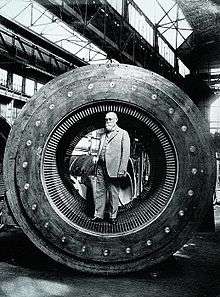

In 1878, the Ganz company's general manager András Mechwart (1853–1942) founded the Department of Electrical Engineering headed by Károly Zipernowsky (1860–1939). Engineers Miksa Déri (1854–1938) and Ottó Bláthy (1860–1939) also worked at the department producing direct-current machines and arc lamps.

In the autumn of 1884, Károly Zipernowsky, Ottó Bláthy and Miksa Déri (ZBD), three engineers associated with the Ganz factory, had determined that open-core devices were impracticable, as they were incapable of reliably regulating voltage.[51] In their joint 1885 patent applications for novel transformers (later called ZBD transformers), they described two designs with closed magnetic circuits where copper windings were either a) wound around iron wire ring core or b) surrounded by iron wire core.[52] The two designs were the first application of the two basic transformer constructions in common use to this day, which can as a class all be termed as either core form or shell form (or alternatively, core type or shell type), as in a) or b), respectively (see images).[53][54][55][56] The Ganz factory had also in the autumn of 1884 made delivery of the world's first five high-efficiency AC transformers, the first of these units having been shipped on September 16, 1884.[57] This first unit had been manufactured to the following specifications: 1,400 W, 40 Hz, 120:72 V, 11.6:19.4 A, ratio 1.67:1, one-phase, shell form.[57] In both designs, the magnetic flux linking the primary and secondary windings traveled almost entirely within the confines of the iron core, with no intentional path through air (see Toroidal cores below). The new transformers were 3.4 times more efficient than the open-core bipolar devices of Gaulard and Gibbs.[58]

The ZBD patents included two other major interrelated innovations: one concerning the use of parallel connected, instead of series connected, utilization loads, the other concerning the ability to have high turns ratio transformers such that the supply network voltage could be much higher (initially 1,400 to 2,000 V) than the voltage of utilization loads (100 V initially preferred).[59][60] When employed in parallel connected electric distribution systems, closed-core transformers finally made it technically and economically feasible to provide electric power for lighting in homes, businesses and public spaces.[61][62] Bláthy had suggested the use of closed cores, Zipernowsky had suggested the use of parallel shunt connections, and Déri had performed the experiments;[63] The other essential milestone was the introduction of 'voltage source, voltage intensive' (VSVI) systems'[64] by the invention of constant voltage generators in 1885.[65] Ottó Bláthy also invented the first AC electricity meter.[66][67][68][69] Transformers today are designed on the principles discovered by the three engineers. They also popularized the word 'transformer' to describe a device for altering the emf of an electric current,[61][70] although the term had already been in use by 1882.[71][72] In 1886, the ZBD engineers designed, and the Ganz factory supplied electrical equipment for, the world's first power station that used AC generators to power a parallel connected common electrical network, the steam-powered Rome-Cerchi power plant.[73] The reliability of the AC technology received impetus after the Ganz Works electrified a large European metropolis: Rome in 1886.[73]

Turbogenerators

The first turbo-generators were water turbines which propelled electric generators. The first Hungarian water turbine was designed by the engineers of the Ganz Works in 1866, the mass production with dynamo generators started in 1883.[74] The manufacturing of steam turbo generators started in the Ganz Works in 1903.

In 1905, the Láng Machine Factory company also started the production of steam turbines for alternators.[75]

Light Bulbs, Radio tubes and X-ray

Tungsram is a Hungarian manufacturer of light bulbs and vacuum tubes since 1896. On 13 December 1904, Hungarian Sándor Just and Croatian Franjo Hanaman were granted a Hungarian patent (No. 34541) for the world's first tungsten filament lamp. The tungsten filament lasted longer and gave brighter light than the traditional carbon filament. Tungsten filament lamps were first marketed by the Hungarian company Tungsram in 1904. This type is often called Tungsram-bulbs in many European countries.[76] Their experiments also showed that the luminosity of bulbs filled with an inert gas was higher than in vacuum. The tungsten filament outlasted all other types (especially the former carbon filaments). The British Tungsram Radio Works was subsidiary of the Hungarian Tungsram in pre WW2 days.

Despite the long experimentation with vacuum tubes at Tungsram company, the mass production of radio tubes begun during the ww1,[77] and the production of X-ray tubes started also during the WW1 in Tungsram Company.[78]

Home appliances

The Orion Electronics was founded in 1913. Its main profiles were the production of electrical switches, sockets, wires, incandescent lamps, electric fans, electric kettles, and various household electronics.

Telecommunication

The first telegraph station on Hungarian territory was opened in December 1847 in Pressburg/ Pozsony /Bratislava/. In 1848, – during the Hungarian Revolution – another telegraph centre was built in Buda to connect the most important governmental centres. The first telegraph connection between Vienna and Pest – Buda (later Budapest) was constructed in 1850.[79] In 1884, 2,406 telegraph post offices operated in the Kingdom of Hungary.[80] By 1914 the number of telegraph offices reached 3,000 in post offices, and a further 2,400 were installed in the railway stations of the Kingdom of Hungary.[81]

The first Hungarian telephone exchange was opened in Budapest (May 1, 1881).[82] All telephone exchanges of the cities and towns in the Kingdom of Hungary were linked in 1893.[79] By 1914, more than 2,000 settlements had telephone exchange in the Kingdom of Hungary.[81]

The Telefon Hírmondó (Telephone Herald) service was established in 1893. Two decades before the introduction of radio broadcasting, residents of Budapest could listen to news, cabaret, music and opera at home and in public spaces daily. It operated over a special type of telephone exchange system and its own separate network. The technology was later licensed in Italy and the United States. (see: telephone newspaper).

The first Hungarian telephone factory (Factory for Telephone Apparatuses) was founded by János Neuhold in Budapest in 1879, which produced telephones microphones, telegraphs, and telephone exchanges.[83][84][85]

In 1884, the Tungsram company also started to produce microphones, telephone apparatuses, telephone switchboards and cables.[86]

The Ericsson company also established a factory for telephones and switchboards in Budapest in 1911.[87]

Navigation and Shipbuilding

The first Hungarian steamship was built by Antal Bernhard in 1817, called S.S. "Carolina". It was also the first steamship in Habsburg ruled states.[88] The daily passenger traffic between the two sides of the Danube by the Carolina started in 1820.[89] The regular cargo and passenger transports between Pest and Vienna began in 1831.[88] However it was Count István Széchenyi (with the help of Austrian ship's company Erste Donaudampfschiffahrtsgesellschaft (DDSG) ), who established the Óbuda Shipyard on the Hungarian Hajógyári Island in 1835, which was the first industrial scale steamship building company in the Habsburg Empire.[90] The most important seaport for the Hungarian part of the k.u.k. was Fiume (Rijeka, today part of Croatia), where the Hungarian shipping companies, such as the Adria, operated. The largest Hungarian shipbuilding company was the Ganz-Danubius. In 1911, The Ganz Company merged with the Danubius shipbuilding company, which largest shipbuilding company in Hungary. Since 1911, the unified company adopted the "Ganz - Danubius" brand name. As Ganz Danubius, the company became involved in shipbuilding before, and during, World War I. Ganz was responsible for building the dreadnought Szent István, supplied the machinery for the cruiser Novara.

Diesel-electric Military Submarines:

The Ganz-Danubius company started to build U-boats at its shipyard in Budapest, for final assembly at Fiume. Several U-Boats of the U-XXIX class, U-XXX class, U-XXXI class and U-XXXII class were completed ,[91] and a number of other types were laid down, remaining incomplete at the war's end.[92] The company built some ocean liners too.

In 1915, the Whitehead company established one of its largest enterprise, the Hungarian Submarine Building Corporation (or in its German name: Ungarische Unterseebotsbau AG (UBAG)) in Fiume, Kingdom of Hungary (Now Rijeka, Croatia).[93][94] SM U-XX, SM U-XXI, SM U-XXII and SM U-XXIII Type diesel-electric submarines were produced by the UBAG Corporation in Fiume.[95][96]

Communist Era (1947–1989)

References

- ↑ http://oldwww.uni-miskolc.hu/uni/univ/booklet/MandU.html

- ↑ http://www.moveonnet.eu/directory/institution?id=HUBUDAPES02

- ↑ Wolfschmidt, Gudrun (ed.): Cultural Heritage of Astronomical Observatories – From Classical Astronomy to Modern Astrophysics Proceedings of the International ICOMOS Symposium in Hamburg, 14–17 October 2008. ICOMOS – International Council on Monuments and Sites. Berlin: hendrik Bäßler-Verlag (Monuments and Sites XVIII) 2009.pp 155–157

- ↑ Astron. Nachr. /AN 328 (2007), No. 7 – Short Contributions AG2007 Würzburg 1 A Pioneer of the Theory of Stellar Spectra – Radó von Kövesligethy Lajos Balázs, Magda Vargha and E. Zsoldos Konkoly Observatory of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences P.O.Box 67, H-1525 Budapest: The first successful spectral equation of black body radiation was the theory of continuous spectra of celestial bodies by Radó von Kövesligethy (published 1885 in Hungarian, 1890 in German). Kövesligethy made several assumptions on the matter-radiation interaction. Based on these assumptions, he derived a spectral equation with the following properties: the spectral distribution of radiation depends only on the temperature, the total irradiated energy is finite (15 years before Planck!), the wavelength of the intensity maximum is inversely proportional to the temperature (eight years before Wien!). Using his spectral equation, he estimated the temperature of several celestial bodies, including the Sun. As a byproduct he developed a theory of the spectroscopic instruments

- ↑ The Contribution of Hungarians to Universal Culture (includes inventors), Embassy of the Republic of Hungary, Damascus, Syria, 2006.

- ↑ Miskolczi, F.M. (2007) Greenhouse effect in semi-transparent planetary atmospheres, Quarterly Journal of the Hungarian Meteorological Service Vol. 111, No. 1, January–March 2007, pp. 1–40

- ↑ Science Watch November 2010

- ↑ http://www.thebrainprize.org

- ↑ coach. CollinsDictionary.com. Collins English Dictionary - Complete & Unabridged 11th Edition. Retrieved November 07, 2012.

- ↑ Definition "coach" in Merriam-Webster Dictionary.

- 1 2 "IEC – Techline Otto Blathy, Miksa Déri, Károly Zipernowsky". Iec.ch. Retrieved 20 September 2009.

- ↑ ■Design Patent 2333807 by Joseph Mihalyi filed in 1936, granted 1943 {shown on Google Patents}

- ↑ Kodak Camera Design

- ↑ http://www.physics.org/explorelink.asp?id=1037&q=scanning%20tunneling%20microscope¤tpage=2&age=0&knowledge=0&item=14

- ↑ Lohr, Steve (17 September 2002). "A Microsoft Pioneer Leaves to Strike Out on His Own". The New York Times. Retrieved 21 May 2008.

- ↑ Fildes, Jonathan (26 October 2006). "'Nerd' outlines space ambitions". BBC News. Retrieved 21 May 2008.

- ↑ Dániel Rátai participated with his invention at the finals of the Intel – International Science and Engineering Fair world competition in 2005 in Phoenix, Arizona. Rátai's invention garnered six first prizes from the jury composed of international experts: IEEE Computer Society, First Award; Patent and Trademark Office Society, First Award; Intel Foundation Achievement Awards; Computer Science – Presented by Intel Foundation, Best of Category; Computer Science – Presented by Intel Foundation, First Award; Seaborg SIYSS Award. “Big corporations and research institutions have spent billions of dollars over decades to solve this problem. Meanwhile, this 19-year-old kid has cobbled this gizmo together using straws, Christmas tree lights and wire," one American juror's commented."

- ↑ Székesfehérvár MJV – Hírportál – 3D Alba – Hungarian invention the three dimensional scanner microscope

- ↑ Rolt and Allen, p:145

- ↑ Conrad Matschoss: Great engineers, page:93

- ↑ L. T. C. Rolt, John Scott Allen: The steam engine of Thomas Newcomen, page:61

- ↑ William Chambers: Chambers's encyclopaedia -PAGE: 176

- ↑ http://vasutgepeszet.hu/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/201404_03-06_vegl.pdf

- ↑ (Béla Czére, Ákos Vaszkó): Nagyvasúti Vontatójármüvek Magyarországon, Közlekedési Můzeum, Közlekedési Dokumentációs Vállalat, Budapest, 1985, ISBN 9635521618

- ↑ Wolfgang Lübsen: Die Orientbahn und ihre Lokomotiven. in: Lok-Magazin 57, Dezember 1972, S. 448–452

- ↑ Mikulas Teich, Roy Porter: The Industrial Revolution in National Context: Europe and the USA (page: 266.)

- ↑ Tibor Iván Berend (2003). History Derailed: Central and Eastern Europe in the Long Nineteenth Century (in Hungarian). University of California Press. p. 152; 330. ISBN 978-0-520-23299-0.

- ↑ "HIPO HIPO – KÁLMÁN KANDÓ (1869–1931)". Sztnh.gov.hu. 2004-01-29. Retrieved 2013-03-25.

- ↑ Michael C. Duffy (2003). Electric Railways 1880-1990. IET. p. 137. ISBN 978-085296805-5.

- ↑ "Kalman Kando". Retrieved 2011-10-26.

- ↑ "Kalman Kando". Retrieved 2009-12-05.

- ↑ Michael C. Duffy (2003). Electric Railways 1880-1990. IET. p. 137. ISBN 9780852968055.

- ↑ Hungarian Patent Office. "Kálmán Kandó (1869–1931)". www.mszh.hu. Retrieved 2008-08-10.

- ↑ History of Public Transport in Hungary. Book: Zsuzsa Frisnyák: A magyarországi közlekedés krónikája, 1750–2000

- ↑ Tramways in Croatia: Book: Vlado Puljiz, Gojko Bežovan, Teo Matković, dr. Zoran Šućur, Siniša Zrinščak: Socijalna politika Hrvatske

- ↑ Trams & Tramways in Romania

- ↑ Tramways in Slovakia: Book: Július Bartl: Slovak History: Chronology & Lexicon – p. 112

- ↑ István Tisza and László Kovács: A magyar állami, magán- és helyiérdekű vasúttársaságok fejlődése 1876–1900 között, Magyar Vasúttörténet 2. kötet. Budapest: Közlekedési Dokumentációs Kft., 58–59, 83–84. o. ISBN 9635523130 (1996)(English: The development of Hungarian private and state owned commuter railway companies between 1876 – 1900, Hungarian railway History Volume II.

- ↑ Kogan Page: Europe Review 2003/2004, fifth edition, Wolden Publishing Ltd, 2003, page 174

- ↑ "The History of BKV, Part 1". Bkv.hu. 1918-11-22. Retrieved 2013-03-25.

- ↑ UNESCO

- ↑ Iván Boldizsár: NHQ; the New Hungarian Quarterly - Volume 16, Issue 2; Volume 16, Issues 59-60 - Page 128

- ↑ Hungarian Technical Abstracts: Magyar Műszaki Lapszemle - Volumes 10-13 - Page 41

- ↑ Joseph H. Wherry: Automobiles of the World: The Story of the Development of the Automobile, with Many Rare Illustrations from a Score of Nations (Page:443)

- ↑ The history of the biggest pre-War Hungarian car maker

- ↑ COMMERCE REPORTS VOLUME 4 - Page 223 (printed in 1927)

- ↑ G.N. Georgano: The New Encyclopedia of Motorcars, 1885 to the Present. S. 59.

- ↑ The American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics (AIAA): History of Flight from Around the World: Hungary article.

- ↑ Mária Kovács: SHORT HISTORY OF HUNGARIAN AVIATION

- ↑ http://www.nyugatijelen.com/riport/az_aradi_autogyartas_sikertortenetebol.php

- ↑ Hughes, p. 95

- ↑ Uppenborn, F. J. (1889). History of the Transformer. London: E. & F. N. Spon. pp. 35–41.

- ↑ Del Vecchio, Robert M.; et al. (2002). Transformer Design Principles: With Applications to Core-Form Power Transformers. Boca Raton: CRC Press. pp. 10–11, Fig. 1.8. ISBN 90-5699-703-3.

- ↑ Knowlton, p. 562

- ↑ Károly, Simonyi. "The Faraday Law With a Magnetic Ohm's Law". Természet Világa. Retrieved Mar 1, 2012.

- ↑ Lucas, J.R. "Historical Development of the Transformer" (PDF). IEE Sri Lanka Centre. Retrieved Mar 1, 2012.

- 1 2 Halacsy, A. A.; Von Fuchs, G. H. (April 1961). "Transformer Invented 75 Years Ago". IEEE Transactions of the American Institute of Electrical Engineers. 80 (3): 121–125. doi:10.1109/AIEEPAS.1961.4500994. Retrieved Feb 29, 2012.

- ↑ Jeszenszky, Sándor. "Electrostatics and Electrodynamics at Pest University in the Mid-19th Century" (PDF). University of Pavia. Retrieved Mar 3, 2012.

- ↑ "Hungarian Inventors and Their Inventions". Institute for Developing Alternative Energy in Latin America. Retrieved Mar 3, 2012.

- ↑ "Bláthy, Ottó Titusz". Budapest University of Technology and Economics, National Technical Information Centre and Library. Retrieved Feb 29, 2012.

- 1 2 "Bláthy, Ottó Titusz (1860 - 1939)". Hungarian Patent Office. Retrieved Jan 29, 2004.

- ↑ Zipernowsky, K.; Déri, M.; Bláthy, O.T. "Induction Coil" (PDF). U.S. Patent 352 105, issued Nov. 2, 1886. Retrieved July 8, 2009.

- ↑ Smil, Vaclav (2005). Creating the Twentieth Century: Technical Innovations of 1867—1914 and Their Lasting Impact. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 71.

- ↑ American Society for Engineering Education. Conference - 1995: Annual Conference Proceedings, Volume 2, (PAGE: 1848)

- ↑ Thomas Parke Hughes: Networks of Power: Electrification in Western Society, 1880-1930 (PAGE: 96)

- ↑ Eugenii Katz. "Blathy". People.clarkson.edu. Archived from the original on June 25, 2008. Retrieved 2009-08-04.

- ↑ Ricks, G.W.D. (March 1896). "Electricity Supply Meters". Journal of the Institution of Electrical Engineers. 25 (120): 57–77. doi:10.1049/jiee-1.1896.0005. Student paper read on January 24, 1896 at the Students' Meeting.

- ↑ The Electrician, Volume 50. 1923

- ↑ Official gazette of the United States Patent Office: Volume 50. (1890)

- ↑ Nagy, Árpád Zoltán (Oct 11, 1996). "Lecture to Mark the 100th Anniversary of the Discovery of the Electron in 1897 (preliminary text)". Budapest. Retrieved July 9, 2009.

- ↑ Oxford English Dictionary (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. 1989.

- ↑ Hospitalier, Édouard (1882). The Modern Applications of Electricity. Julius Maier (trans.). New York: D. Appleton & Co. p. 103.

- 1 2 "Ottó Bláthy, Miksa Déri, Károly Zipernowsky". IEC Techline. Retrieved Apr 16, 2010.

- ↑ http://www.sze.hu/~mgergo/EnergiatudatosEpulettervezes/2013_1_feladat/ErosErika/V%EDzenergia%20hasznos%EDt%E1s%20szigetk%F6zi%20szemmel%20EL%D5AD%C1SANYAG.pdf

- ↑ United States. Congress (1910). Congressional Serial Set. U.S. Government Printing Office. pp. 41; 53.

- ↑ http://web.archive.org/web/20050530094858/http://www.tungsram.hu/tungsram/downloads/tungsram/tu_short_history_1896-1996.pdf

- ↑ See: The History of Tungsram 1896-1945" Page: 32

- ↑ See: The History of Tungsram 1896-1945" Page: 33

- 1 2 "Google Drive – Megtekintő". Docs.google.com. Retrieved 2013-03-25.

- ↑ "Telegráf – Lexikon ::". Kislexikon.hu. Retrieved 2013-03-25.

- 1 2 Dániel Szabó, Zoltán Fónagy, István Szathmári, Tünde Császtvay: Kettős kötődés : Az Osztrák-Magyar Monarchia (1867–1918)|

- ↑ Telephone History Institute: Telecom History - Issue 1. page 14.

- ↑ E und M: Elektrotechnik und Maschinenbau. Volume 24. page 658.

- ↑ Eötvös Loránd Matematikai és Fizikai Társulat Matematikai és fizikai lapok. Volumes 39-41. 1932. Publisher: Hungarian Academy of Sciences.

- ↑ Contributor Budapesti Történeti Múzeum: Title: Tanulmányok Budapest múltjából. Volume 18. page 310. Publisher Budapesti Történeti Múzeum, 1971.

- ↑ Károly Jeney; Ferenc Gáspár; English translator:Erwin Dunay (1990). The History of Tungsram 1896-1945 (PDF). Tungsram Rt. p. 11. ISBN 978-3-939197-29-4.

- ↑ IBP, Inc. (2015). Hungary Investment and Business Guide (Volume 1) Strategic and Practical Information World Business and Investment Library. lulu.com. p. 128. ISBN 9781514528570.

- 1 2 Iván Wisnovszky, Study trip to the Danube Bend, Hydraulic Documentation and Information Centre, 1971, p. 13

- ↑ "185 éve indult el az első dunai gőzhajó". mult-kor.hu. 15 July 2005. Retrieved 2014-05-09.

- ↑ Victor-L. Tapie: The Rise and Fall of the Habsburg Monarchy PAGE: 267

- ↑ R.H. Gibson; Maurice Prendergast (2002). The German Submarine War 1914-1918. Periscope Publishing Ltd. p. 386. ISBN 9781904381082.

- ↑ http://www.gwpda.org/naval/ahsubs.htm Sieche article on KuK U-Boats

- ↑ Paul G. Halpern (2015). The Naval War in the Mediterranean: 1914-1918 (Routledge Library Editions: Military and Naval History ed.). Routledge. p. 158. ISBN 978-131739186-9.

- ↑ Lawrence Sondhaus (1994). The Naval Policy of Austria-Hungary, 1867-1918: Navalism, Industrial Development, and the Politics of Dualism. Purdue University Press. p. 287. ISBN 978-155753034-9.

- ↑ Lawrence Sondhaus (1994). The Naval Policy of Austria-Hungary, 1867-1918: Navalism, Industrial Development, and the Politics of Dualism. Purdue University Press. p. 303. ISBN 978-155753034-9.

- ↑ Paul E. Fontenoy (2007). Submarines: An Illustrated History of Their Impact Weapons and warfare series. ABC-CLIO. p. 170. ISBN 978-185109563-6.