Shaykhism

| |

|---|

|

|

|

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| The Fourteen Infallibles | |||

|

|||

| Principles | |||

| Other beliefs | |||

| Practices | |||

| Holy cities | |||

| Groups | |||

|

|

|||

| Scholarship | |||

| Hadith collections | |||

| Related topics | |||

| Related portals | |||

|

|||

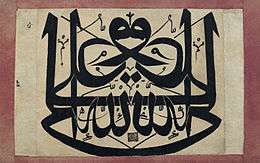

Shaykhism (Arabic: الشيخية) is an Islamic religious movement founded by Shaykh Ahmad[1] in early 19th century Qajar Iran. It began from pure Shi‘a doctrine of the end times and the day of resurrection. Today the Shaykhi populations retain a minority following in Iran and Iraq.[2] In the mid 19th century many Shaykhis converted to the Bábí and Bahá'í religions, which regard Shaykh Ahmad highly.[3][4]

Shaykhí teachings

Eschatology

The primary force behind Shaykh Ahmad's teachings is the Twelver Shi'a belief in the occultation of the Twelfth Imam. Twelver Shi'ah believe there were twelve Imams starting with Ali and ending with Muhammad al-Mahdi. While the first eleven Imams died, the twelfth is said to have disappeared, to return "before the day of judgment" and "fill the Earth with justice and make the truth triumphant". This messianic figure is called the Mahdi.

The source of knowledge and certainty

Shaykhí teachings on knowledge are similar in appearance to that of the Sufis, save that where the Sufi "wayfarer" arrogates to himself the role of interpreting and adjudicating truth, Shaykh Ahmad was clear that the final arbiter for interpretation and clarity was the 12th Imam.

"For Shaykh Ahmad, then, the Shi`ite learned man is not simply a mundane thinker dependent on nothing more than the divine text and his intellectual tools for its interpretation. The Learned must have a spiritual pole (qutb), a source of grace (ghawth), who will serve as the locus of God's own gaze in this world. Both pole and ghawth are frequently-used Sufi terms for great masters who can by their grace help their followers pursue the spiritual path. For Shaykh Ahmad, the pole is the Twelfth Imam himself, the light of whose being is in the heart of the Learned. The oral reports, he notes, say that believers benefit from the Imam in his Occultation just as the earth benefits from the sun even when it goes behind a cloud. Were the light of the Imam, as guardian (mustahfiz), to be altogether extinguished, then the Learned would not be able to see in the darkness."[5]

Mystical symbology and the origin of the Prophet

Shaykh Ahmad's perspectives on accepted Islamic doctrines diverged in several areas, most notably on his mystical interpretation of prophesy. The sun, moon and stars of the Qur'an's eschatological surahs are seen as allegorical, where common Muslim interpretation is that events involving celestial bodies will happen literally at the Day of Judgment. In other writings, Shaykh Ahmad synthesizes rather dramatic descriptions of the origin of the prophets, the primal word, and other religious themes through allusions and mystical language. Much of this language is oriented around trees, specifically the primal universal tree of Eden, described in Jewish scripture as being two trees. This primal tree is, in some ways, the universal spirit of the prophets themselves:

The symbol of the preexistent tree appears elsewhere in Shaykh Ahmad's writings. He says, for instance, that the Prophet and the Imams exist both on the level of unconstrained being or preexistence, wherein they are the Complete Word and the Most Perfect Man, and on the level of constrained being. On this second, limited plane, the cloud of the divine Will subsists and from it emanates the Primal Water that irrigates the barren earth of matter and of elements. Although the divine Will remains unconstrained in essential being, its manifest aspect has now entered into limited being. When God poured down from the clouds of Will on the barren earth, he thereby sent down this water and it mixed with the fallow soil. In the garden of the heaven known as as-Saqurah, the Tree of Eternity arose, and the Holy Spirit or Universal Intellect, the first branch that grew upon it, is the first creation among the worlds.[6]

This notion of beings with both divine and ephemeral natures presages a similar doctrine of the Manifestation in Bábism and the Bahá'í faiths, religions whose origins are rooted in the Shaykhi spiritual tradition.

Leadership of the movement

Shaykh Ahmad

Shaykh Ahmad, at about age forty, began to study in earnest in the Shi'a centres of religious scholarship such as Karbala and Najaf. He attained sufficient recognition in such circles to be declared a mujtahid, an interpreter of Islamic Law. He contended with Sufi and Neo-Platonist scholars, and attained a positive reputation among their detractors. Most interestingly, he declared that all knowledge and sciences were contained (in essential form) within the Qur'an, and that to excel in the sciences, all knowledge must be gleaned from the Qur'an. His views resulted in his denunciation by several learned clerics, and he engaged in many debates before moving on to Persia where he settled for a time in the province of Yazd. It was in Isfahan that most of this was written.

Sayyid Kazim Rashti

Shaykh Ahmad led the sect for only two years before his death. His undisputed[7] successor also led the Shaykhís until his own death (1843). Siyyid Kázim said that he would not live to see the Promised One, but, according to the Bábís, his appearance was so imminent that Siyyid Kázim appointed no successor, instead instructing his followers to spread across the land and search him out.

Sayyid Kazim did not explicitly appoint a successor. Rather, convinced that the Mahdi was in the world, he encouraged his followers to seek him out.[8] Many of the Shaykhis expected Mullá Husayn, one of his favorite pupils, to take on the mantle. Mullá Husayn, however, declined the honor, insisting on obedience to Sayyid Kazim's final commands to go out in search of the Mahdi. Many of the followers of Shaykh Ahmad spread out as did Mullah Husayn. By 1844, two perspectives had emerged and camps arose based on the differing claims of two individuals.

Mullah Husayn and Siyyid Alí-Muhammad (The Báb)

On May 23, 1844, during his search for the Mahdi, Mullá Husayn encountered a young man in Shiraz named Siyyid Alí-Muhammad. Ali-Muhammad had visited some of Siyyid Kazim's classes, and later tellings assert that Siyyid Kazim implied a connection between his own predictions about the Mahdi and this Alí-Muhammad attending his class. Ali-Muhammad, in that same May 23 meeting, took the title of the Báb and claimed to be the gate between the Shi'a and the hidden Twelfth Imam. He only claimed to be the Imam in person a short time before his death in 1850. Mullá Husayn ultimately accepted this claim, as did many leading Shaykhi students. Most of these went on to become the earliest Bábís. The Báb was ultimately labeled a heretic, thrown into prison and was executed July 9, 1850. Most of the Bábís turned to the well known Bábí community leader Bahá'u'lláh who founded the Bahá'í Faith in claiming that he was the one prophesied by the Báb. Both Babís and Bahá'ís regard Shaykhi thought as a precursor to their own religious traditions. A full account of Shaykhi-Babi links and the influence of Shaykhi thought on the Bab may be found in D. MacEoin, The Messiah of Shiraz. A firsthand account of the history and relationship between Siyyid Kazim, Mullah Husayn and the Báb from a Bábí perspective is can be found in Nabíl's Narrative (also known as "The Dawn-Breakers") by Muhammad-i-Zarandí (surnamed Nabíl-i-A'zam), translated into English by Shoghi Effendi Rabbani, Guardian of the Baha'i Faith, 1921-1957.

Karim Khan

Haji Karim Khan Kirmani (1809/1810-1870/1871) became the leader of the main Shaykhi group that did not follow the Bab. He became the foremost critic of the Bab, writing four essays against him.[9] Baha'u'llah in turn described Karim as "foolishness masquerading as knowledge"[10] Karim repudiated some of the more radical teachings of Ahsai and Rashti and moved the Shaykhi school back towards the mainstream Usuli teachings. Karim Khan Kirmani was succeeded by his son Shaykh Muhammad Khan Kirmani (1846–1906), then by Muhammad's brother Shaykh Zaynal 'Abidln Kirmani (1859–1946). Shaykh Zayn al-'Abidin Kirmani was succeeded by Shaykh Abu al-Qasim Ibrahimi (1896–1969), who was succeeded by his son 'Abd al-Rida Khan Ibrahimi who was a leader until his death.[11]

Relationship to Bábism and the Bahá'í Faith

Bábis and then Bahá'ís see Shaykhism as a spiritual ancestor of their movement, preparing the way for the Báb and eventually Bahá'u'lláh. In this view Shaykhism has outlived its eschatological purpose and is no longer anymore relevant.[12]

Modern Shaykhism

The current leader of the Shaykhiya is Ali al-Musawi, who heads a community with followers in Iraq - mainly Basrah and Karbala - Iran and the Persian Gulf. Basrah has a significant Shaykhi minority, and their mosque is one of the largest in the city holding up to 12,000 people. The Shaykhiya were resolutely apolitical and hence were allowed relative freedom under Saddam Hussein. Since the 2003 Invasion of Iraq and subsequent Iraqi Civil War they have been targeted by Iraqi nationalists who accused them of being Saudis on the grounds that Ahmad al-Ahsai was from present-day Saudi Arabia. They responded by creating an armed militia and asking all local political groups to sign a pact allowing them to live in peace. This was done at the al-Zahra conference in April 2006.[13] In a move away from their traditional apolitical stance, a Shaykhi political party stood in the Basra governorate election, 2009; they came third, winning 5% of the votes and 2 out of 35 seats.[14]

In Iran Shaykhism is regarded as the third Twelver Shi'a denomination after Usulism and Akhbarism. In their public explanations the Shaykhis have come so close to normative Usuli doctrine that Usulis have expressed some wonder at why the Shaykhis have maintained their separate existence.

References

- ↑ MacEoin, D.M. "SHAIKH AḤMAD AḤSĀʾĪ". Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- ↑ "The Encyclopedia of World History". bartleby.com. 2001. Retrieved 2006-10-10.

- ↑ Amanat, Abbas (1989). Resurrection and Renewal: The Making of the Babi Movement in Iran. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. pp. 174, 261–272.

- ↑ Effendi, Shoghi (1944). God Passes By. Wilmette, Illinois, USA: Bahá'í Publishing Trust. p. 92. ISBN 0-87743-020-9.

- ↑ Cole, Juan (September 1997). "Individualism and the Spiritual Path in Shaykh Ahmad al-Ahsa'i". H-Net (H-Baha'i), Occasional Papers in Shaykhi, Babi and Baha'i Studies.

- ↑ Cole, Juan (1994). "The World as Text: Cosmologies of Shaykh Ahmad al-Ahsa'i". University of Michigan - Studia Islamica 80 (1994):1-23.

- ↑ Nabíl-i-Zarandí (1932). Shoghi Effendi (Translator), ed. The Dawn-Breakers: Nabíl’s Narrative (Hardcover ed.). Wilmette, Illinois, USA: Bahá'í Publishing Trust. p. 16. ISBN 0-900125-22-5.

- ↑ Nabíl-i-Zarandí (1932). Shoghi Effendi (Translator), ed. The Dawn-Breakers: Nabíl’s Narrative (Hardcover ed.). Wilmette, Illinois, USA: Bahá'í Publishing Trust. p. 47. ISBN 0-900125-22-5.

- ↑ Scholarship on the Baha'i Faith, Moojan Momen

- ↑ See Kitab-i-Aqdas, 170

- ↑ Henry Corbin History of Islamic Philosophy, Vol. II; page 353

- ↑ Smith, P. (1999). A Concise Encyclopedia of the Bahá'í Faith. Oxford, UK: Oneworld Publications. pp. 216–217 & 312. ISBN 1-85168-184-1.

- ↑ Where Is Iraq Heading? Lessons from Basra, International Crisis Group, 2007-06-25, accessed on 2007-07-03

- ↑ The Candidate Lists Are Out: Basra More Fragmented, Sadrists Pursuing Several Strategies?, Historiae, 2008-12-12

External links

- Early Shaykhism: Some Bibliographical Notes, Translations and Studies by Stephen Lambden

- Collected Works of Shaykh Ahmad al-Ahsa'i at H-Bahai Discussion Network

- Al-Abrar; Digital Library of Shaykhia