Slaughterhouse

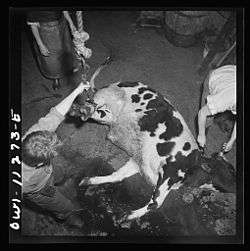

A slaughterhouse or abattoir ![]() i/ˈæbətwɑːr/ is a facility where animals are slaughtered for consumption as food for humans.[1] Slaughterhouses that process meat not intended for human consumption are sometimes referred to as knacker's yards or knackeries, used for animals that are not fit for consumption or can no longer work on a farm such as horses that can no longer work.

i/ˈæbətwɑːr/ is a facility where animals are slaughtered for consumption as food for humans.[1] Slaughterhouses that process meat not intended for human consumption are sometimes referred to as knacker's yards or knackeries, used for animals that are not fit for consumption or can no longer work on a farm such as horses that can no longer work.

Slaughtering animals on a large scale poses significant logistical problems, animal welfare problems, public health requirements, and environmental problems. [1] Due to public aversion in many cultures, determining where to build slaughterhouses is also troubling.

Animal welfare and animal rights groups frequently raise concerns about the methods of transport, preparation, herding, and killing within some slaughterhouses under the example of animal rights activists such as Howard Lyman and Ric O'Barry.[2]

Productivity

Quintessentially, about half of the animal can be turned into meat. Some parts of an animal are waste and the remaining half of the animal is turned into animal products such as leather, soaps, candles (tallow), and animal glue.

History

Until modern times, the slaughter of animals generally took place in a haphazard and unregulated manner in diverse places. Early maps of London show numerous stockyards in the periphery of the city, where slaughter occurred in the open air. A term for such open-air slaughterhouses was shambles, and there are streets named "The Shambles" in some English towns (e.g. Worcester, York) which got their name from having been the site on which butchers killed and prepared animals for consumption.

Reform movement

The slaughterhouse emerged as a coherent institution in the nineteenth century.[3] A combination of health and social concerns, exacerbated by the rapid urbanisation experienced during the Industrial Revolution, led social reformers to call for the isolation, sequester and regulation of animal slaughter. As well as the concerns raised regarding hygiene and disease, there were also criticisms of the practice on the grounds that the effect that killing had, both on the butchers and the observers, "educate[d] the men in the practice of violence and cruelty, so that they seem to have no restraint on the use of it." An additional motivation for eliminating private slaughter was to impose a careful system of regulation for the "morally dangerous" task of putting animals to death.

As a result of this tension, meat markets within the city were closed and abattoirs built outside city limits. An early framework for the establishment of public slaughterhouses was put in place in Paris in 1810, under the reign of the Emperor Napoleon. Five areas were set aside on the outskirts of the city and the feudal privileges of the guilds were curtailed.[4]

As the meat requirements of the growing number of residents in London steadily expanded, the meat markets both within the city and beyond attracted increasing levels of public disapproval. Meat had been traded at Smithfield Market as early as the 10th century. By 1726, it was regarded as "without question, the greatest in the world", by Daniel Defoe.[5] By the middle of the 19th century, in the course of a single year 220,000 head of cattle and 1,500,000 sheep would be "violently forced into an area of five acres, in the very heart of London, through its narrowest and most crowded thoroughfares".[6]

By the early 19th century, pamphlets were being circulated arguing in favour of the removal of the livestock market and its relocation outside of the city due to the extremely poor hygienic conditions[7] as well as the brutal treatment of the cattle.[8] In 1843, the Farmer's Magazine published a petition signed by bankers, salesmen, aldermen, butchers and local residents against the expansion of the livestock market.[6]

An Act of Parliament was finally passed in 1852. Under its provisions, a new cattle-market was constructed in Copenhagen Fields, Islington. The new Metropolitan Cattle Market was also opened in 1855, and West Smithfield was left as waste ground for about a decade, until the construction of the new market began in the 1860s under the authority of the 1860 Metropolitan Meat and Poultry Market Act.[9] The market was designed by architect Sir Horace Jones and was completed in 1868.

A cut and cover railway tunnel was constructed beneath the market to create a triangular junction with the railway between Blackfriars and Kings Cross.[10] This allowed animals to be transported into the slaughterhouse by train and the subsequent transfer of animal carcasses to the Cold Store building, or direct to the meat market via lifts.

At the same time, the first large and centralized slaughterhouse in Paris was constructed in 1867 under the orders of Napoleon III at the Parc de la Villette and heavily influenced the subsequent development of the institution throughout Europe.

Regulation and expansion

These slaughterhouses were regulated by law to ensure good standards of hygiene, the prevention of the spread of disease and the minimization of needless animal cruelty. The slaughterhouse had to be equipped with a specialized water supply system to effectively clean the operating area of blood and offal. Veterinary scientists, notably George Fleming and John Gamgee, campaigned for stringent levels of inspection to ensure that epizootics such as rinderpest (a devastating outbreak of the disease covered all of Britain in 1865) would not be able to spread. By 1874, three meat inspectors were appointed for the London area, and the Public Health Act 1875 required local authorities to provide central slaughterhouses (they were only given powers to close insanitary slaughterhouses in 1890).[11]

Attempts were also made at reforming the practice of slaughter itself, as the methods used came under increasing criticism for causing undue pain to the animals. The eminent physician, Benjamin Ward Richardson, spent many years in developing more humane methods of slaughter. He brought into use no less than fourteen possible anesthetics for use in the slaughterhouse and even experimented with the use of electric current at the Royal Polytechnic Institution.[12] As early as 1853, he designed a lethal chamber that would gas animals to death relatively painlessly, and he founded the Model Abattoir Society in 1882 to investigate and campaign for humane methods of slaughter.

The invention of refrigeration and the expansion of transportation networks by sea and rail allowed for the safe exportation of meat around the world. Additionally, Meat-packing millionaire Philip Danforth Armour’s invention of the 'disassembly line' greatly increased the productivity and profit margin of industrial meatpacking businesses: "according to some, animal slaughtering became the first mass-production industry in the United States." This expansion has been accompanied by increased concern about the physical and mental conditions of the workers along with controversy over the ethical and environmental implications of slaughtering animals for meat.[3]

Design

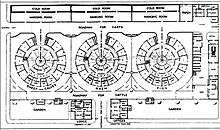

In the latter part of the 20th century, the layout and design of most U.S. slaughterhouses was influenced by the work of Dr. Temple Grandin.[13] She suggested that reducing the stress of animals being led to slaughter may help slaughterhouse operators improve efficiency and profit.[14] In particular she applied an understanding of animal psychology to design pens and corrals which funnel a herd of animals arriving at a slaughterhouse into a single file ready for slaughter. Her corrals employ long sweeping curves[15][16][17] so that each animal is prevented from seeing what lies ahead and just concentrates on the hind quarters of the animal in front of it. This design – along with the design elements of solid sides, solid crowd gate, and reduced noise at the end point – work together to encourage animals forward in the chute and to not reverse direction.[18]

As of 2011, Grandin claimed to have designed over 54% of the slaughterhouses in the United States as well as many others around the world.

Mobile design

By 2010 a mobile facility the Modular Harvest System had received USDA approval. It can be moved from ranch to ranch. It consists of three trailers, one for slaughtering, one for consumable body parts and one for other body parts. Preparation of individual cuts is done at a butchery or other meat preparation facility.[19]

International variations

The standards and regulations governing slaughterhouses vary considerably around the world. In many countries the slaughter of animals is regulated by custom and tradition rather than by law. In the non-Western world, including the Arab world, the Indian sub-continent, etc., both forms of meat are available: one which is produced in modern mechanized slaughterhouses, and the other from local butcher shops.

In some communities animal slaughter and permitted species may be controlled by religious laws, most notably halal for Muslims and kashrut for Jewish communities. This can cause conflicts with national regulations when a slaughterhouse adhering to the rules of religious preparation is located in some Western countries. In Jewish law, captive bolts and other methods of pre-slaughter paralysis are generally not permissible, due to it being forbidden for an animal to be stunned prior to slaughter. Various halal food authorities have more recently permitted the use of a recently developed fail-safe system of head-only stunning where the shock is non-fatal, and where it is possible to reverse the procedure and revive the animal after the shock. The use of electronarcosis and other methods of dulling the sensing has been approved by the Egyptian Fatwa Committee. This allows these entities to continue their religious techniques while keeping accordance to the national regulations.[20]

In some societies, traditional cultural and religious aversion to slaughter led to prejudice against the people involved. In Japan, where the ban on slaughter of livestock for food was lifted in the late 19th century, the newly found slaughter industry drew workers primarily from villages of burakumin, who traditionally worked in occupations relating to death (such as executioners and undertakers). In some parts of western Japan, prejudice faced by current and former residents of such areas (burakumin "hamlet people") is still a sensitive issue. Because of this, even the Japanese word for "slaughter" (屠殺 tosatsu) is deemed politically incorrect by some pressure groups as its inclusion of the kanji for "kill" (殺) supposedly portrays those who practice it in a negative manner.

Some countries have laws that exclude specific animal species or grades of animal from being slaughtered for human consumption, especially those that are taboo food. The former Indian Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee suggested in 2004 introducing legislation banning the slaughter of cows throughout India, as Hinduism holds cows as sacred and considers their slaughter unthinkable and offensive. This was often opposed on grounds of religious freedom. The slaughter of cows and the importation of beef into the nation of Nepal are strictly forbidden.

Some countries practices sustainable designs that allows minimal waste produced as effluents in nearby bodies of water. In the Philippines, some slaughterhouse were poorly designed as shown by contamination and pollution of nearby rivers [1]

Freezing Works

Refrigeration technology allowed meat from the slaughterhouse to be preserved for longer periods. This led to the concept as the slaughterhouse as a freezing works. Prior to this, canning was an option.[21] Freezing works are common in New Zealand, Australia and South Africa. The countries where meat is exported for a substantial profit the freezing works were built near docks, or near transport infrastructure.[22]

Law

Most countries have laws in regard to the treatment of animals at slaughterhouses. In the United States, there is the Humane Slaughter Act of 1958, a law requiring that all swine, sheep, cattle, and horses be stunned unconscious with application of a stunning device by a trained person before being hoisted up on the line. There is some debate over the enforcement of this act. This act, like those in many countries, exempts slaughter in accordance to religious law, such as kosher shechita and dhabiha halal. Most strict interpretations of kashrut require that the animal be fully sensible when its carotid artery is cut.

The novel The Jungle detailed unsanitary conditions, fictionalized, in slaughterhouses and the meatpacking industry during the 1800s. This led directly to an investigation commissioned directly by President Theodore Roosevelt, and to the passage of the Meat Inspection Act and the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906, which established the Food and Drug Administration. A much larger body of regulation deals with the public health and worker safety regulation and inspection.

Animal welfare concerns

In 1997 Gail Eisnitz, chief investigator for the Humane Farming Association (HFA),[23] released a book Slaughterhouse. Within, she unveils the interviews of slaughterhouse workers in the U.S. who say that, because of the speed with which they are required to work, animals are routinely skinned while apparently alive, and still blinking, kicking, and shrieking. Eisnitz argues that this is not only cruel to the animals, but also dangerous for the human workers, as cows weighing several thousands of pounds thrashing around in pain are likely to kick out and debilitate anyone working near them.[24]

This would imply that certain slaughterhouses throughout the country are not following the guidelines and regulations spelled out by the Humane Slaughter Act, requiring all animals to be put down and thus insusceptible to pain by some form, typically electronarcosis, before undergoing any form of violent action.

According to the HFA, Eiznitz interviewed slaughterhouse workers representing over two million hours of experience, who, without exception, told her that they have beaten, strangled, boiled, and dismembered animals alive, or have failed to report those who do. The workers described the effects the violence has had on their personal lives, with several admitting to being physically abusive or taking to alcohol and other drugs.[25]

The HFA alleges that workers are required to kill up to 1,100 hogs an hour, and end up taking their frustration out on the animals.[25] Eisnitz interviewed one worker, who had worked in ten slaughterhouses, about pig production. He told her:

Hogs get stressed out pretty easy. If you prod them too much, they have heart attacks. If you get a hog in the chute that's had the shit prodded out of him and has a heart attack or refuses to move, you take a meat hook and hook it into his bunghole. You try to do this by clipping the hipbone. Then you drag him backwards. You're dragging these hogs alive, and a lot of times the meat hook rips out of the bunghole. I've seen hams — thighs — completely ripped open. I've also seen intestines come out. If the hog collapses near the front of the chute, you shove the meat hook into his cheek and drag him forward.[26]

Fish

Historically, some doubted that fish could experience pain. However, laboratory experiments have shown that fish do react to painful stimuli (e.g. injections of bee venom) in a similar way to mammals.[27][28] The expansion of fish farming as well as animal welfare concerns in society has led to research into more humane and faster ways of killing fish.[29] In large-scale operations like fish farms, stunning fish with electricity or putting them into water saturated with nitrogen so that they cannot breathe, results in death more rapidly than just taking them out of the water. For sport fishing, it is recommended that fish be killed soon after catching them by hitting them on the head followed by bleeding out, or by stabbing the brain with a sharp object[30] (called pithing or ike jime in Japanese).

See also

- Ag-Gag

- Beef ring

- Bubbly Creek

- Controlled-atmosphere killing (CAK)

- Environmental impact of meat production

- Pig slaughter

- Pig scalder

- Union Stock Yards

References

- 1 2 3 Canencia, Oliva P; Dalugdug, Marlou D; Emano, Athena Marie; Mendoza, Richard; Walag, Angelo Mark P. (2016-08-31). "Slaughter waste effluents and river catchment watershed contamination in Cagayan de Oro City, Philippines". ResearchGate. 9 (2). ISSN 2220-6663.

- ↑ "Top 10 Animal Rights Activists". Belief Net.

- 1 2 "A Social History of the Slaughterhouse" (PDF). Human Ecology Review.

- ↑ Paula Young Lee (2008). Meat, Modernity, and the Rise of the Slaughterhouse. UPNE. p. 26.

- ↑ Defoe, Daniel (1726). A Tour Through the Whole Island of Great Britain. p. 342. ISBN 0-300-04980-3.

- 1 2 The Farmer's Magazine. London: Rogerson and Tuxford, 1849. 1849. p. 142.

- ↑ Dodd, George (1856). The Food of London: A Sketch of the Chief Varieties, Sources of Supply, Probable Quantities, Modes of Arrival, Processes of Manufacture, Suspected Adulteration, and Machinery of Distribution, of the Food for a Community of Two Millions and a Half. Longman, Brown, Green and Longmans. p. 228.

- ↑ Kean, Hilda (1998). "'Wild' domestic animals and the Smithfield Market". Animal rights: political and social change in Britain since 1800. Reaktion Books. p. 59. ISBN 1-86189-014-1.

- ↑ Thornbury, Walter (1878). "The Metropolitan Meat-Market". Old and New London: Volume 2. pp. 491–496. Retrieved 2008-02-01.

- ↑ Snowhill (London Railways) accessed 13 April 2009

- ↑ Chris Otter (2006). "The vital city: public analysis, dairies and slaughterhouses in nineteenth-century" (PDF). Cultural Geographies.

- ↑

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Power, D'Arcy (1901). "Richardson, Benjamin Ward". In Sidney Lee. Dictionary of National Biography, 1901 supplement. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Power, D'Arcy (1901). "Richardson, Benjamin Ward". In Sidney Lee. Dictionary of National Biography, 1901 supplement. London: Smith, Elder & Co. - ↑ Grandin, T. "Best Practices for Animal Handling and Stunning"", Meat & Poultry, April 2000, p.76.

- ↑ Grandin, T. and Deesing, M. "Humane Livestock Handling" 2008. Storey Publishing, North Adams, MA, USA.

- ↑ Grandin, Temple (September 2011). "Directions for laying out curved cattle handling facilities for ranches, feedlots, and properties". Dr. Temple Grandin's Web Page. Dr. Temple Grandin. Retrieved 2012-12-10. "Round crowd pens and curved single file chutes work better than straight ones, but they must be laid out correctly. A curved chute works more efficiently than a straight one because it prevents cattle from seeing people and other activities at the end of the chute." "A round crowd pen will work better than a straight crowd pen because, as cattle go around a 180° turn, they think they are going back to where they came from "

- ↑ Grandin, Temple (July 2011). "Sample Designs of Cattle Races and Corrals". Dr. Temple Grandin's Web Page. Dr. Temple Grandin. Retrieved 2012-12-10. Why does a curved chute and round crowd pen work better than a straight one? As the animals go around the curve, they think they are going back to where they came from. The animals can not see people and other moving objects at the end of the chute. It takes advantage of the natural circling behaviour of cattle and sheep.

- ↑ Grandin, Temple (1993). "Teaching Principles of Behavior and Equipment Design for Handling Livestock". J. Anim. Sci. J. Anim. Sci. Retrieved 2012-12-10. Some of the design principles that are taught are the use of solid sides on chutes and crowd pens to prevent animals from seeing out with their wide-angle vision and layout of curved chutes and round crowd pens. Some people believe the animals can smell or hear death, however, and these may be area that need improvement, such as the use of scent masking agents or acoustical barriers. As well, some animals in some situations may grow to learn that after their fellows are corralled in that area, their fellows never return. An improvement could be made by detouring off some of the animals so that they return to the pack (after the odors and sounds are masked so they will return untraumatized). A circular crowd pen and a curved chute reduced the time spent moving cattle by up to 50% (Vowles and Hollier, 1982 [Vowles, W. J., and T. J. Hollier. 1982. The influence of yard design on the movement of animals. Proc. Aust. Soc. Anim. Prod. 14:597]).

- ↑ Grandin, Temple (July 2010). "Improving the Movement of Cattle, Pigs, and Sheep during handling on farms, ranches, and slaughter plants". Dr Temple Grandin. Retrieved 2012-12-10. Cattle will move more easily through a curved race. Solid sides which prevent the cattle from seeing people and other distractions outside the fence should be installed on the chutes (races) and the crowd pen which leads up to the single file chute. The use of solid sides is especially important in slaughter plants, truck loading ramps, and other places where there is lots of activity outside the fence. Solid sides are essential in slaughter plants to block the animal's view of people and equipment. A curved chute (race) with solid sides at a ranch facility. It works better than a straight chute because cattle think they are going back to where they came from. The outer fence is solid to prevent the cattle from seeing distractions outside the fence... The facility must be located in a pasture that has no nearby equipment, moving vehicles or extra people, or put inside a building that has solid side walls. In many facilities, adding solid fences will improve animal movement... Solid sides in these areas help prevent cattle from becoming agitated when they see activity outside the fence -- such as people. Cattle tend to be calmer in a chute with solid sides. Cattle move more easily through the curved race system because they can not see people and other distractions ahead.

- ↑ Muhlke, Christine (23 May 2010). "FIELD REPORT; A Movable Beast". The New York Times. p. 22.

- ↑ "The Opinions of the Ulema on the Permissibility of Stunning Animals". Egyptian Fatwaa Committee. December 18, 1978.

- ↑ Techhistory.co.nz

- ↑ Teara.govt.nz

- ↑ Humane Farming Association Website

- ↑ Eisnitz, Gail A. Slaughterhouse. Prometheus Books, 1997, cited in Torres, Bob. Making a Killing. AK Press, 2007, p. 46.

- 1 2 "HFA Exposé Uncovers Federal Crimes", Humane Farming Association. Retrieved March 8, 2008.

- ↑ Eisnitz, p. 82, cites in Torres, Bob. Making a Killing. AK Press, 2007, p. 47.

- ↑ Sneddon, LU (2009). "Pain perception in fish: indicators and endpoints.". ILAR Journal. 50 (4): 38–42. PMID 19949250.

- ↑ Oidtmann, B; Hoffman, RW (Jul–Aug 2001). "Pain and suffering in fish". Berliner und Münchener tierärztliche Wochenschrift. 114 (7-8): 277–82. PMID 11505801.

- ↑ Lund, V; Mejdell, CM; Röcklinsberg, H; Anthony, R; Håstein, T (2007-05-04). "Expanding the moral circle: farmed fish as objects of moral concern.". Diseases of aquatic organisms. 72 (2): 109–118. doi:10.3354/dao075109. PMID 17578250.

- ↑ Davie, PS; Kopf, RK (August 2006). "Physiology, behaviour and welfare of fish during recreational fishing and after release.". New Zealand veterinary journal. 54 (4): 161–172. doi:10.1080/00480169.2006.36690. PMID 16915337.

External links

| Look up slaughterhouse in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Abattoir. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Slaughterhouses. |

- Slaughterhouse designer Temple Grandin's official site detailing her design principles, as well as many of the regulations affecting slaughter in the United States.

- Surveys of Stunning and Handling in Slaughter Plants Grandin's listing of various surveys, 1996–2011, US, Canada and Australia