Southern American English

Southern American English or Southern U.S. English is a collection of related American English dialects spoken throughout the Southern United States, though increasingly in more rural areas and primarily by white Americans.[1] Commonly in the United States, the dialects are together simply referred to as Southern.[2][3][4] Other, much more recent ethno-linguistic terms within the U.S. include Southern White Vernacular English and Rural White Southern English.[5][6]

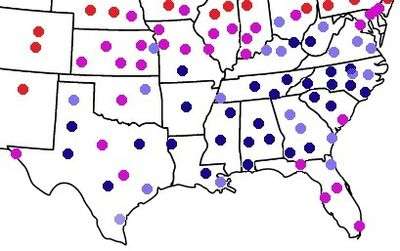

A regional Southern American English consolidated and expanded throughout all the traditional Southern States since the last quarter of the nineteenth century until around World War II,[7][8] largely superseding the older Southern American English dialects. With this more unified and younger pronunciation system, Southern American English now comprises the largest accent group in the United States.[9] As of 2006, its Southern accent is strongly reported throughout the U.S. states of Virginia, Kentucky, North Carolina, South Carolina (excluding the Charleston area), Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Tennessee, Arkansas, and Louisiana, as well as much of Texas, southern Missouri, West Virginia, and metropolitan Jacksonville in Florida; the Southern accent's character is also documented to a weaker extent (often identified as a South Midland accent) throughout Oklahoma, Maryland, Kansas, the southern halves of Illinois and Indiana, the Miami Valley in Ohio, and in some speakers in Delaware, southern Pennsylvania, and Greater St. Louis in eastern Missouri.[10]

Southern American English as a regional dialect can be divided into various sub-dialects, the most phonologically advanced ones being southern varieties of Appalachian English and scattered varieties of Texan English. African American Vernacular English (AAVE) has many common points with Southern English dialects due to the strong historical ties of African Americans to the region.

|

|

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

|

|

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

|

|

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

Geography

The dialects collectively known as Southern American English stretch across the south-eastern and south-central United States, but exclude the southernmost areas of Florida and the extreme western and south-western parts of Texas as well as the Rio Grande Valley (Laredo to Brownsville). This linguistic region includes Alabama, Georgia, Tennessee, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Louisiana, and Arkansas, as well as most of Texas, Virginia, Kentucky, Oklahoma, West Virginia, and northern and central Florida. Southern American English dialects can also be found in extreme southern parts of Missouri, Maryland, Delaware, and Illinois.[11][12]

Southern dialects originated in large part from a mix of immigrants from the British Isles, who moved to the American South in the 17th and 18th centuries, and the creole or post-creole speech of African slaves. Upheavals such as the Great Depression, the Dust Bowl and World War II caused mass migrations of those and other settlers throughout the United States.

Phonology of the Southeastern super-region

Headed by William Labov, the 2006 Atlas of North American English (ANAE) identifies the South itself, as well a large area of states bordering all along the South, as constituting a "Southeastern super-region",[15] with even remote (including arguably Northern) areas that phonologically exhibit some noticeable "Southern character".[15] Essentially all of the modern-day Southern dialects, plus dialects marginal to the South, are thus considered a subset of this super-region.[note 1] Thus, a modern Southeastern dialectal super-region is defined by essentially the whole American South, including all of the Gulf region (even Florida), the Mid- and South Atlantic regions, and a transitional Midland dialect area between the South and the North, lying above the strict Southern region and comprising most of Oklahoma, Kansas, Missouri, southeastern Nebraska, Southern Illinois, Southern Indiana, and Southern Ohio.[16] Put perhaps in clearer terms, the Southeastern super-dialect region encompasses all of these most general regional American dialects:

- Southern dialect(s)

- Midland dialect

- Mid-Atlantic dialect

- English of the areas inside or just outside the Southern region, but without yet any well-studied "unique defining character", such as northern Florida.[17]

These are the minimal necessary features that identify a speaker from the Southeastern super-region:

- Fronting of /aʊ/ and /oʊ/: The gliding vowels /aʊ/ (as in cow or ouch) and /oʊ/ (as in goat or bone) both start considerably forward in the mouth, approximately [ɛɔ~æɒ] and [ɜu], respectively. /oʊ/ may even end in a very forward position[18]—something like [ɜy~œʏ]. However, this fronting does not occur in younger speakers before /l/ (as in goal or colt) or before a syllable break between two vowels (as in going or poet), in which /oʊ/ remains back in the mouth as [ɔu~ɒu].[19]

- Lacking or transitioning cot–caught merger: The historical distinction between the two vowels sounds /ɔː/ and /ɒ/, in words like caught and cot or stalk and stock is mainly preserved.[15] In much of the South during the 1900s, there was a trend to lower the vowel found in words like stalk and caught, often with an upglide, so that the most common result today is the gliding vowel [ɑɒ]. However, the cot–caught merger is becoming increasingly common throughout the United States, thus affecting Southeastern and even some Southern dialects, towards a merged vowel [ɑ].[20] In the South, this merger, or a transition towards this merger, is especially documented in central, northern, and (particularly) western Texas.[21]

- Card–cord merger: The vowel in /ɑːr/ (as in part or star) is often rounded to [ɒɻ],[22] perhaps even merging with /ɔːr/, so that words like stork and stark become identical in sound.

- Pin–pen merger in transition: The vowels [ɛ] and [ɪ] often merge when before nasal consonants, so that pen and pin, for instance, or hem and him, are pronounced the same, as pin or him, respectively.[15] The merger is towards the sound [ɪ]. This merger is now firmly completed throughout the Southern dialect region; however, it is not found in some vestigial varieties of the older South, and other geographically Southern U.S. varieties that have eluded the Southern Vowel Shift, such as the Yat dialect of New Orleans or the anomalous dialect of Savannah, Georgia. The pin–pen merger has also spread beyond the South in recent decades and is now found in isolated parts of the West and the southern Midwest as well.

- Rhoticity: The pronunciation of the r sound only before or between vowels (but not after vowels) was historically widespread in the South, particularly in former plantation areas. This phenomenon, non-rhoticity, was considered prestigious before World War II, after which the social perception in the South reversed. Now, rhoticity (sometimes called r-fulness), in which all r sounds are pronounced, has become dominant throughout the entire Southeastern super-region, as in most American English, and even more so among younger and female white Southern speakers; the only major exception is among African American Southerners, whose modern vernacular dialect continues to be mostly non-rhotic.[23] The sound quality of the Southern r is the distinctive "bunch-tongued r", produced by strongly constricting the root and/or midsection of the tongue.[24]

The South

| Pure vowels (Monophthongs) | ||

|---|---|---|

| English diaphoneme | Southern phoneme | Example words |

| /æ/ | [æ~æjə] | act, pal, trap |

| [eə~æjə] | ham, land, yeah | |

| /ɑː/ | [ɑ] | blah, bother, father, lot, top, wasp |

| /ɒ/ | ||

| [ɔo~ɑɒ~ɑ] | all, dog, bought, loss, saw, taught | |

| /ɔː/ | ||

| /ɛ/ | [ɛ~ɛjə] preceding a nasal consonant: [ɪ~ɪ(ʲ)ə] |

dress, met, bread |

| /ə/ | [ə] | about, syrup, arena |

| /ɪ/ | [ɪ~ɪjə] | hit, skim, tip |

| /iː/ | [ɪi] | beam, chic, fleet |

| /ɨ/ | [ɪ~ɪ̈~ə] | island, gamut, wasted |

| /ʌ/ | [ɜ] | bus, flood, what |

| /ʊ/ | [ʊ̈~ʏ] | book, put, should |

| /uː/ | [ʊu~ɵu~ʊ̈y] | food, glue, new |

| Diphthongs | ||

| /aɪ/ | [äː~äɛ] | ride, shine, try |

| ([ɐi~äɪ~äɛ]) | bright, dice, psych | |

| /aʊ/ | [æɒ~ɛjɔ] | now, ouch, scout |

| /eɪ/ | [ɛi] | lake, paid, rein |

| /ɔɪ/ | [oi] | boy, choice, moist |

| /oʊ/ | [ɜʊ~ɜʊ̈~ɜʏ] preceding /l/ or a hiatus: [ɔu] |

goat, oh, show |

| R-colored vowels | ||

| /ɑr/ | rhotic Southern dialects: [ɒɚˠ~ɑɚˠ] non-rhotic Southern dialects: [ɒː~ɑː] |

barn, car, park |

| /ɛər/ | rhotic: [e̞ɚˠ~ɛ(ʲ)ɚˠ] non-rhotic: [ɛ(ʲ)ə] |

bare, bear, there |

| /ɜr/ | [ɚˠ~ɐɚˠ] (older: [ɜ~ə]) | burn, first, herd |

| /ər/ | rhotic:[ɚˠ] non-rhotic:[ə] |

better, martyr, doctor |

| /ɪər/ | rhotic: [iɚˠ] non-rhotic: [iə] |

fear, peer, tier |

| /ɔr/ | rhotic: [o(u)ɚˠ] non-rhotic: [o(u)ə] |

hoarse, horse, poor score, tour, war |

| /ɔər/ | ||

| /ʊər/ | ||

| /jʊər/ | rhotic: [juɚˠ~jɚˠ] non-rhotic: [juə] |

cure, Europe, pure |

The South proper as a present-day dialect region generally includes all of the pronunciation features of the larger Southeastern super-region, plus additional features listed below, which are together popularly recognized in the United States as a "Southern accent". However, there is still actually wide variation in Southern speech regarding potential differences based on factors like a speaker's exact sub-region, age, ethnicity, etc. The following phonological phenomena focus on the developing sound system of the more recent Southern dialects of the United States that altogether largely (though certainly not entirely) superseded the older Southern regional patterns:

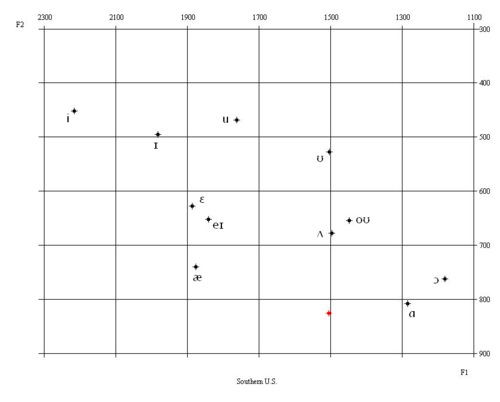

- Southern Vowel Shift (or Southern Shift): A chain shift regarding vowels is fully completed, or occurring, in most Southern dialects, especially younger ones, and at the most advanced stage in the "Inland South" (i.e. away from the coastline) and "Texas South" (i.e. most of central and northern Texas). This 3-stage chain movement of vowels, called the Southern Shift, is first triggered by Stage 1 that dominates the entire Southern region, followed by Stage 2 that covers almost all of that area, and Stage 3 that is concentrated only in speakers of certain core sub-regions. Stage 1 (defined below) may have begun in some Southern dialects as early as the first half of the 1800s with a glide weakening of /aɪ/ to [aɛ] or [aə]; however, it was still largely incomplete or absent in the mid-1800s, before expanding rapidly from the last quarter of the 1800s into the middle 1900s;[27] today, this glide weakening or even total glide deletion is the pronunciation norm throughout all of the Southern United States.

- Stage 1 (/aɪ/ → [aː] and /æ/ → [ɛ(j)ə]):

- The starting point, or first stage, of the Southern Shift is the transition of the gliding vowel (diphthong) /aɪ/ (

listen) towards a "glideless" long vowel [aː~äː] (

listen) towards a "glideless" long vowel [aː~äː] ( listen), so that, for example, the word ride commonly approaches a sound that most other American English speakers would hear as rod or rad. Stage 1 is now complete for a majority of Southern dialects.[28] Southern speakers particularly exhibit the Stage 1 shift at the ends of words and before voiced consonants, but not before voiceless consonants, where the diphthong instead retains its glide, so that ride is [ɹäːd], but right is [ɹäɪt]. Inland (i.e. non-coastal) Southern speakers, however, delete the glide of /aɪ/ in all contexts, as in the stereotyped pronunciation "nahs whaht rahss" for nice white rice; these most shift-advanced speakers are largely found today in an Appalachian area that comprises eastern Tennessee, western North Carolina and northern Alabama, as well as in central Texas.[29] Some traditional East Coast Southern accents do not exhibit this Stage 1 glide deletion,[30] particularly in Charleston, SC and possibly Atlanta and Savannah, GA (cities that are, at best, considered marginal to the modern Southern dialect region).

listen), so that, for example, the word ride commonly approaches a sound that most other American English speakers would hear as rod or rad. Stage 1 is now complete for a majority of Southern dialects.[28] Southern speakers particularly exhibit the Stage 1 shift at the ends of words and before voiced consonants, but not before voiceless consonants, where the diphthong instead retains its glide, so that ride is [ɹäːd], but right is [ɹäɪt]. Inland (i.e. non-coastal) Southern speakers, however, delete the glide of /aɪ/ in all contexts, as in the stereotyped pronunciation "nahs whaht rahss" for nice white rice; these most shift-advanced speakers are largely found today in an Appalachian area that comprises eastern Tennessee, western North Carolina and northern Alabama, as well as in central Texas.[29] Some traditional East Coast Southern accents do not exhibit this Stage 1 glide deletion,[30] particularly in Charleston, SC and possibly Atlanta and Savannah, GA (cities that are, at best, considered marginal to the modern Southern dialect region). - This new glideless [aː~äː] vowel encroaches on the territory of the "short a" vowel, /æ/ (as in rat or bad), thus pushing /æ/ generally higher and fronter in the mouth (and also possibly giving it a complex gliding quality, often starting higher and then gliding lower); thus /æ/ can range variously away from its original position: [æ(j)ə~æɛæ~ɛ(j)ə>ɛ]. An example is that, to other English speakers, the Southern pronunciation of yap sounds something like yeah-up.

- The starting point, or first stage, of the Southern Shift is the transition of the gliding vowel (diphthong) /aɪ/ (

- Stage 2 (/eɪ/ → [ɛɪ] and /ɛ/ → [e(j)ə]):

- By removing the existence of [aɪ], Stage 1 leaves open a lower space for /eɪ/ (as in name and day) to occupy, causing Stage 2: the pulling of the diphthong /eɪ/ into a lower starting position, towards [ɛɪ] or to an even lower and/or more retracted sound.

- At the same time, the pushing of /æ/ into the vicinity of /ɛ/ (as in red or belt), forces /ɛ/ itself into a higher and fronter position, occupying the [e] area (previously the vicinity of /eɪ/). /ɛ/ also often acquires an in-glide: thus, [e(j)ə]. An example is that, to other English speakers, the Southern pronunciation of yep sounds something like yay-up. Stage 2 is most common in heavily stressed syllables. Southern accents originating from cities that formerly had the greatest influence and wealth in the South (Richmond, VA; Charleston, SC; Atlanta, Macon, and Savannah, GA; and all of Florida) do not traditionally participate in Stage 2.[31]

- Stage 3 (/i/ → [ɪi] and /ɪ/ → [iə]): By the same pushing and pulling domino effects described above, /ɪ/ (as in hit or lick) and /i/ (as in beam or meet) follow suit by both possibly becoming diphthongs whose nuclei switch positions. /ɪ/ may be pushed into a diphthong with a raised beginning, [iə], while /i/ may be pulled into a diphthong with a lowered beginning, [ɪi]. An example is that, to other English speakers, the Southern pronunciation of fin sounds something like fee-in, while meal sounds something like mih-eel. Like the other stages of the Southern shift, Stage 3 is most common in heavily stressed syllables and particularly among Inland Southern speakers.[31]

- Southern vowel breaking ("Southern drawl"): All three stages of the Southern Shift often result in the short front pure vowels being "broken" into gliding vowels, making one-syllable words like pet and pit sound as if they might have two syllables (as something like pay-it and pee-it respectively). This short front vowel gliding phenomenon is popularly recognized as the "Southern drawl". The "short a", "short e", and "short i" vowels are all affected, developing a glide up from their original starting position to [ɪ], and then often back down to a schwa vowel: /æ/ → [æjə~ɛjə]; /ɛ/ → [ɛjə~ejə]; and /ɪ/ → [ɪjə~ijə], respectively. This phenomenon is on the decline, being most typical of Southern speakers born before 1960,[32] though mostly after the mid-1800s.

- Stage 1 (/aɪ/ → [aː] and /æ/ → [ɛ(j)ə]):

- Unstressed, word-final /ŋ/ → [n]: The phoneme /ŋ/ in an unstressed syllable at the end of a word fronts to [n], so that singing /ˈsɪŋɪŋ/ is sometimes written phonetically as singin [ˈsɪŋɪn].[33] This is common in vernacular English dialects around the world.

- Lax and tense vowels often neutralize before /l/, making pairs like feel/fill and fail/fell homophones for speakers in some areas of the South. Some speakers may distinguish between the two sets of words by reversing the normal vowel sound, e.g., feel in Southern may sound like fill, and vice versa.[34]

- The back vowel /u/ (in goose or true) is fronted in the mouth to the vicinity of /ʉ/ or even farther forward, which is then followed by a slight gliding quality; different gliding qualities have been reported, including both backward and (especially in the eastern half of the South) forward glides.[35]

- Back Upglide (Chain) Shift: In Southern regional (and Southeastern super-regional) dialects, /aʊ/ shifts forward and upward to [æʊ] (also possibly realized, variously, as [æjə~æo~ɛɔ~eo]); thus allowing the back vowel /ɔː/ to fill an area similar to the former position of /aʊ/ in the mouth, becoming lowered and developing an upglide [ɑɒ]; this, in turn, allows (though only for the most advanced Southern speakers) the upgliding /ɔɪ/, before /l/, to lose its glide [ɔː] (for instance, causing the word boils to sound something like the British or New York City pronunciations of

balls).[36]

balls).[36] - The vowel /ʌ/, as in bug, luck, strut, etc., is realized as [ɜ], occasionally fronted to [ɛ̈] or raised in the mouth to [ə]. In former plantation areas, a more backed form, [ʌ], is common among older speakers.[37]

- /z/ becomes [d] before /n/, for example [ˈwʌdn̩t] wasn't, [ˈbɪdnɪs] business,[38] but hasn't may keep the [z] to avoid merging with hadn't.

- Many nouns are stressed on the first syllable that are stressed on the second syllable in most other American accents.[32] These may include police, cement, Detroit, Thanksgiving, insurance, behind, display, hotel, motel, recycle, TV, guitar, July, and umbrella. Today, younger Southerners tend to keep this initial stress for a more reduced set of words, perhaps including only insurance, defense, and umbrella.[39]

- Lacking or incomplete happy tensing: The tensing of unstressed, word-final /ɪ/ (the second vowel sound in words like happy, money, Chelsea, etc.) to a higher and fronter vowel like [i] is typical throughout the United States, except in the South. The South maintains a sound not obviously tensed: [ɪ] or [ɪ~i].[40]

- Words ending in unstressed /oʊ/ may be pronounced more like /ə/, making yellow sound like yella or tomorrow like tomorra.

Inland South and Texas

ANAE identifies the "Inland South" as a large linguistic area of the South located mostly in southern Appalachia (specifically naming the cities of Greenville SC, Asheville NC, Knoxville and Chatanooga TN, and Birmingham and Linden AL), inland from both the Gulf and Atlantic Coasts, and the originating region of the Southern Vowel Shift. The Inland South, along with the "Texas South" (an urban core of central Texas: Dallas, Lubbock, Odessa, and San Antonio)[10] are considered the two major locations in which the Southern regional sound system is the most evolved, and therefore the core areas of the current-day South as a dialect region.[41]

The accents of Texas are actually diverse, for example with important Spanish influences on its vocabulary;[42] however, much of the state is still an unambiguous region of modern rhotic Southern speech, strongest in the cities of Dallas, Lubbock, Odessa, and San Antonio,[10] which all firmly demonstrate the first stage of the Southern Shift, if not also further stages of the shift.[43] Texan cities that are noticeably "non-Southern" dialectally are Abilene and Austin; only marginally Southern are Houston, El Paso, and Corpus Christi.[44] In western and northern Texas, the cot–caught merger is very close to completed.[45]

Atlanta, Charleston, and Savannah

The Atlas of North American English identifies Atlanta, Georgia as a dialectal "island of non-Southern speech",[46] Charleston, South Carolina likewise as "not markedly Southern in character", and the traditional local accent of Savannah, Georgia as "giving way to regional [Midland] patterns",[47] despite these being three prominent Southern cities. The dialect features of Atlanta are best described today as sporadic from speaker to speaker, with such variation increased due to a huge movement of non-Southerners into the area during the 1990s.[48] Modern-day Charleston speakers have leveled in the direction of a more generalized Midland accent, away the city's now-defunct but traditional Lowcountry accent, whose features were "diametrically opposed to the Southern Shift... and differ in many other respects from the main body of Southern dialects".[49] The Savannah accent is also becoming more Midland-like. The following vowel sounds of Atlanta, Charleston, and Savannah have been unaffected by typical Southern phenomena like the Southern drawl and Southern Vowel Shift:[48]

- /æ/ as in bad (the "default" General American nasal short-a system is in use, in which /æ/ is tensed only before /n/ or /m/).[49]

- /aɪ/ as in bide (however, some Atlanta and Savannah speakers do variably show Southern /aɪ/ glide weakening).

- /eɪ/ as in bait.

- /ɛ/ as in bed.

- /ɪ/ as in bid.

- /iː/ as in bead.

- /ɔː/ as in bought (which is lowered, as in most of the U.S., and approaches [ɒ~ɑ]; the cot–caught merger is mostly at a transitional stage in these cities).

However, the modern accents of Atlanta, Charleston, and Savannah do incorporate many of the general Southeastern super-regional features listed above and can be regarded roughly as varieties of Midland English;[48][50] some speakers from all three cities (though most consistently Charleston and least consistently in Savannah) demonstrate the Southeastern fronting of /oʊ/. The status of the pin–pen merger is highly variable in all three cities.[50] Non-rhoticity (r-dropping) is now rare in these cities, yet still documented in some speakers.[51]

Southern Louisiana

Southern Louisiana, as well as some of southeast Texas (Houston to Beaumont), and coastal Mississippi, feature a number of dialects influenced by other languages beyond English. Most of southern Louisiana constitutes Acadiana, dominated for hundreds of years by monolingual speakers of Cajun French,[52] which combines elements of Acadian French with other French and Spanish words. This French dialect is spoken by many of the older members of the Cajun ethnic group and is said to be dying out. A related language called Louisiana Creole also exists.

Acadiana

Since the early 1900s, Cajuns of southern Louisiana, though historically monolingual French speakers, began to develop their own vernacular dialect of English, which retains some influences and words from Acadian/Cajun French, such as "cher" (dear) or "nonc" (uncle). This dialect fell out of fashion after World War II, but experienced a renewal in primarily male speakers born since the 1970s, who have been the most appealed by, and the biggest appealers for, a successful Cajun cultural renaissance.[52] Speakers of Cajun Vernacular English demonstrate these major features, among many others:[53]

- Non-rhoticity (or r-dropping), for the most part.

- High nasalization, even in vowels before nasal consonants.

- Deletion of any word's final consonant(s): Examples are that hand becomes [hæ̃], food becomes [fuː], rent becomes [ɹɪ̃], New York becomes [nuˈjɔə], and so on.[53]

- Universal glide weakening: A particular process of glide weakening is common in the South for certain gliding vowels; however, Cajun English is distinct in that every single English gliding vowel is subject to glide weakening or deletion. For instance, /oʊ/ (as in Joe), /eɪ/ (as in jay), and /ɔɪ/ (as in joy) have somewhat or entirely reduced glides: [oː], [eː], and [ɔː], respectively.[53]

- Cot–caught merger towards [ä].[53]

New Orleans

One historical English dialect spoken only by those raised in the Greater New Orleans area is non-rhotic and noticeably shares more pronunciation commonalities (due to very strong historical ties) with the New York accent than with other Southern accents. Since at least the 1980s, this local New Orleans dialect has popularly been called "Yat", from the common local greeting "Where you at?". The New York City English features shared with this dialect include:[48]

- Non-rhoticity.

- Short-a split system (so that bad and back, for example, have different vowels).

- /ɔː/ as high, often with a glide [ɔə].

- /ɑːr/ as rounded [ɒː~ɔː].

- Coil–curl merger (traditionally, though now in decline).

Yat also lacks the typical vowel changes of the Southern Shift and the pin–pen merger that are commonly heard elsewhere throughout the South. Yat is associated with the working and lower middle classes, though a spectrum with fewer notable Yat features is often heard the higher one's socioeconomic status; such New Orleans affluence is associated with the New Orleans Uptown and the Garden District, and its speech patterns are sometimes considered a separate variety altogether from the Yat dialect.[54]

Additionally, many unique terms such as "neutral ground"[55] for the median of a divided street (Louisiana/Southern Mississippi) or "banquette"[56] for a sidewalk (southern Louisiana/eastern Texas) are found in New Orleans and elsewhere in coastal Louisiana.

Phonology of the older South

Prior to becoming a phonologically unified dialect region, the South was once home to an array of much more diverse accents at the local level. Features of the deeper interior South largely became the basis for the newer Southern regional dialect and Southeastern super-regional dialect discussed above; thus, older Southern American English primarily refers to the English spoken in the coastal and former plantation areas of the South, best documented before the Civil War, on the decline during the early 1900s, and basically non-existent in speakers born since the Civil Rights Era.[57]

Very little unified these older Southern dialects, since they never formed a single homogeneous dialect region to begin with. Some older Southern accents were rhotic (most strongly in Appalachia and west of the Mississippi), while the majority were non-rhotic (most strongly in plantation areas); however, wide variation existed. Some older Southern accents showed (or approximated) Stage 1 of the Southern Vowel Shift—namely, the glide weakening of /aɪ/—however, it is virtually unreported before the very late 1800s.[58] In general, the older Southern dialects clearly lacked the Mary–marry–merry, cot–caught, horse–hoarse, wine–whine, full–fool, fill–feel, and do–dew mergers, all of which are now common to, or encroaching on, all varieties of present-day Southern American English. Older Southern sound systems included those local to:[5]

- Plantation South (the Black Belt excluding the Lowcountry): phonologically characterized by /aɪ/ glide weakening, non-rhoticity (for some accents, including a coil–curl merger), and the Southern trap–bath split (a version of the trap–bath split unique to older Southern U.S. speech that causes words like lass [ɫæs~ɫæɛæs] not to rhyme with words like pass [pʰæes]).

- Eastern and central Virginia (often identified as the "Tidewater accent"): further characterized by Canadian raising and some vestigial resistance to the vein–vain merger.

- Lowcountry (of South Carolina and Georgia; often identified as the traditional "Charleston accent"): characterized by no /aɪ/ glide weakening, non-rhoticity (including the coil-curl merger), the Southern trap–bath split, Canadian raising, the cheer–chair merger, /eɪ/ pronounced as [e(ə)], and /oʊ/ pronounced as [o(ə)].

- Outer Banks and Chesapeake Bay (often identified as the "Hoi Toider accent"): characterized by no /aɪ/ glide weakening (with the on-glide strongly backed, unlike any other U.S. dialect), the card–cord merger, /aʊ/ pronounced as [aʊ~äɪ], and up-gliding of pure vowels especially before /ʃ/ (making fish sound almost like feesh and ash like aysh). It is the only dialect of the older South still extant on the East Coast, due to being passed on through generations of geographically isolated islanders.

- Appalachian and Ozark Mountains: characterized by strong rhoticity and a tor–tore–tour merger (which still exist in that region), the Southern trap–bath split, plus the original and most advanced instances of the Southern Vowel Shift now defining the whole South.

Grammar and vocabulary

Newer features

- Use of the contraction y'all as the second person plural pronoun.[60] Its uncombined form – you all – is used less frequently.[61]

- When addressing a group, y'all is general (I know y'all) and is used to address the group as a whole, whereas all y'all is used to emphasize specificity of each and every member of the group ("I know all y'all.") The possessive form of Y'all is created by adding the standard "-'s".

- "I've got y'all's assignments here." /ˈjɔːlz/

- Y'all is distinctly separate from the singular you. The statement "I gave y'all my truck payment last week," is more precise than "I gave you my truck payment last week." You (if interpreted as singular) could imply the payment was given directly to the person being spoken to – when that may not be the case.

- Some people misinterpret the phrase "all y'all" as meaning that Southerners use the "y'all" as singular and "all y'all" as plural. However, "all y'all" is used to specify that all members of the second person plural (i.e., all persons currently being addressed and/or all members of a group represented by an addressee) are included; that is, it operates in contradistinction to "some of y'all", thereby functioning similarly to "all of you" in standard English.

- When addressing a group, y'all is general (I know y'all) and is used to address the group as a whole, whereas all y'all is used to emphasize specificity of each and every member of the group ("I know all y'all.") The possessive form of Y'all is created by adding the standard "-'s".

- In rural southern Appalachia an "n" is added to pronouns indicating "one" "his'n" "his one" "her'n" "her one" "Yor'n" "your one" i.e. "his, hers and yours". Another example is yernses. It may be substituted for the 2nd person plural possessive yours.

- "That book is yernses." /ˈjɜːrnzᵻz/

- Use of dove as past tense for dive, drug as past tense for drag, brung as past tense for bring, and drunk as past tense for drink.

Shared newer and older features

These grammatical features are characteristic of both older Southern American English and newer Southern American English.

- Use of done as an auxiliary verb between the subject and verb in sentences conveying the past tense.

- I done told you before.

- Use of done (instead of did) as the past simple form of do, and similar uses of the past participle in place of the past simple, such as seen replacing saw as past simple form of see.

- I only done what you done told me.

- I seen her first.

- Use of other non-standard preterites, Such as drownded as the past tense of drown, knowed as past tense of know, choosed as the past tense of choose, degradated as the past tense of degrade.

- I knowed you for a fool soon as I seen you.

- Use of was in place of were, or other words regularizing the past tense of be to was.

- You was sittin' on that chair.

- Use of been instead of have been in perfect constructions.

- I been livin' here darn near my whole life.

- Use of double modals (might could, might should, might would, used to could, etc.--also called "modal stacking") and sometimes even triple modals that involve oughta (like might should oughta)

- I might could climb to the top.

- I used to could do that.

- Use of (a-)fixin' to, or just "fixing to" in more modern Southern, to indicate immediate future action in place of intending to, preparing to, or about to.

- He's fixin' to eat.

- They're fixing to go for a hike.

- Preservation of older English me, him, etc. as reflexive datives.

- I'm fixin' to paint me a picture.

- He's gonna catch him a big one.

- Saying this here in place of this or this one, and that there in place of that or that one.

- This here's mine and that there is yours.

- Existential It, a feature dating from Middle English which can be explained as substituting it for there when there refers to no physical location, but only to the existence of something.

- It's one lady that lives in town.

- Use of ever in place of every.

- Ever'where's the same these days.

- Use of "over yonder" in place of "over there" or "in or at that indicated place", especially to refer to a particularly different spot, such as in "the house over yonder". Additionally, "yonder" tends to refer to a third, larger degree of distance beyond both "here" and "there", indicating that something is a longer way away, and to a lesser extent, in a wide or loosely defined expanse, as in the church hymn "When the Roll Is Called Up Yonder".[62]

Relationship to African American English

Discussion of "Southern dialect" in the United States popularly refers to those English varieties spoken by white Southerners;[6] however, as a geographic term, it may also encompass the dialects developed among other social or ethnic groups in the South, most prominently including African Americans. Today, African American Vernacular English (AAVE) is a fairly unified variety of English spoken by working- and middle-class African Americans throughout the United States. AAVE exhibits an evident relationship with both older and newer Southern dialects, though the exact nature of this relationship is poorly understood.[63] It is clear that AAVE was influenced by older speech patterns of the Southern United States, where Africans and African Americans were held as slaves until the American Civil War. These slaves originally spoke a diversity of indigenous African languages but picked up English to communicate with one another, their white masters, and the white servants and laborers they often closely worked alongside. Many features of AAVE suggest that it largely developed from nonstandard dialects of colonial English (with some features of AAVE absent from other modern American dialects, yet still existing in certain modern British dialects). However, there is also evidence of the influence of West African languages on AAVE vocabulary and grammar.

It is uncertain to what extent early white Southern English borrowed elements from early African American English versus the other way around. Like many white accents of English once spoken in Southern plantation areas—namely, the Lowcountry, Virginia Piedmont and Tidewater, lower Mississippi Valley, and western Black Belt—the modern-day AAVE accent is mostly non-rhotic (or "r-dropping" ). The presence of non-rhoticity in both black English and older white Southern English is not merely coincidence, though, again, which dialect influenced which is unknown. It is better documented, however, that white Southerners borrowed some morphological processes from black Southerners.

Many grammatical features were used alike by older speakers of white Southern English and African American English more so than by contemporary speakers of the same two varieties. Even so, contemporary speakers of both continue to share these unique grammatical features: "existential it", the word y'all, double negatives, was to mean were, deletion of had and have, them to mean those, the term fixin' to, stressing the first syllable of words like hotel or guitar, and many others.[64] Both dialects also continue to share these same pronunciation features: /ɪ/ tensing, /ʌ/ raising, upgliding /ɔː/, the pin–pen merger, and the most defining sound of the current Southern accent (though rarely documented in older Southern accents): the glide weakening of /aɪ/. However, while this glide weakening has triggered among white Southerners a complicated "Southern Vowel Shift", black speakers in the South and elsewhere on the other hand are "not participating or barely participating" in much of this shift.[65] AAVE speakers also do not front the vowel starting positions of /oʊ/ and /uː/, thus aligning these characteristics more with the speech of nineteenth-century white Southerners than twentieth-century white Southerners.[66]

One strong possibility for the divergence of black American English and white Southern American English (i.e., the disappearance of older Southern American English) is that the civil rights struggles caused these two racial groups "to stigmatize linguistic variables associated with the other group".[67] This may explain some of the differences outlined above, including why all traditionally non-rhotic white Southern accents have shifted to now becoming intensely rhotic.

See also

- Accent perception

- African-American English

- Chicano English

- Drawl

- High Tider

- Regional vocabularies of American English

- Southern literature

- Texan English

Notes

- ↑ The only notable exceptions of the South being a subset of the "Southeastern super-region" are two Southern metropolitan areas, described as such because they participate in Stage 1 of the Southern Vowel Shift, but lack the other defining Southeastern features: Savannah, Georgia and Amarillo, Texas.

References

- ↑ Thomas (2006:4, 11)

- ↑ Stephen J. Nagle & Sara L. Sanders (2003). English in the Southern United States. Cambridge University Press. p. 35. ISBN 9781139436786[This page differentiates between "Traditional Southern" and "New Southern"]

- ↑ "Southern". Dictionary.com. Dictionary.com, based on Random House, Inc. 2014[See definition 7.]

- ↑ "Southern". Merriam-Webster. Merriam-Webster, Inc. 2014[See under the "noun" heading.]

- 1 2 Thomas, Erik R. (2007) "Phonological and phonetic characteristics of African American Vernacular English," Language and Linguistics Compass, 1, 450–75. p. 453

- 1 2 (Thomas (2006)

- ↑ A Handbook of Varieties of English: Volume 1, p. 329

- ↑ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:241)

- ↑ "Do You Speak American: What Lies Ahead". PBS. Retrieved 2007-08-15.

- 1 2 3 Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:126, 131)

- ↑ Map from the Telsur Project. Retrieved 2009-08-03.

- ↑ Map from Craig M. Carver (1987), American Regional Dialects: A Word Geography, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. Retrieved 2009-08-03

- ↑ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:131, 139)

- ↑ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:131, 139)

- 1 2 3 4 Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:137)

- ↑ Southard, Bruce. "Speech Patterns". Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture. Oklahoma Historical Society. Retrieved October 29, 2015.

- ↑ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:141)

- ↑ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:263)

- ↑ Thomas (2006:14)

- ↑ Thomas (2006:9)

- ↑ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:61)

- ↑ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:261)

- ↑ Thomas (2006:16)

- ↑ Thomas (2006:15)

- ↑ Thomas (2006:1–2)

- ↑ Heggarty, Paul et al, eds. (2013). "Accents of English from Around the World". University of Edinburgh.

- ↑ A Handbook of Varieties of English: Volume 1, p. 332.

- ↑ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:244)

- ↑ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:245)

- ↑ A Handbook of Varieties of English: Volume 1, p. 301, 311-312

- 1 2 Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:248)

- 1 2 Thomas (2006:5)

- ↑ Stephen J. Nagle & Sara L. Sanders (2003). English in the Southern United States. Cambridge University Press. p. 151. ISBN 9781139436786.

- ↑ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:69–73)

- ↑ Thomas (2006:10)

- ↑ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:254)

- ↑ Thomas (2006:7)

- ↑ Wolfram (2004:55)

- ↑ A Handbook of Varieties of English: Volume 1, p. 331.

- ↑ Wells, John C. (1988). Accents of English 1: An Introduction. Cambridge University Press. p. 164.

- ↑ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:148, 150)

- ↑ American Varieties: Texan English. Public Broadcasting Service. MacNeil/Lehrer Productions. 2005.

- ↑ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:69)

- ↑ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:131)

- ↑ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:254)

- ↑ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:181)

- ↑ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:304)

- 1 2 3 4 Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:260–1)

- 1 2 Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:259–260)

- 1 2 Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:68)

- ↑ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:48)

- 1 2 Dubois, Sylvia and Barbara Horvath (2004). "Cajun Vernacular English: phonology." In Bernd Kortmann and Edgar W. Schneider (Ed). A Handbook of Varieties of English: A Multimedia Reference Tool. New York: Mouton de Gruyter. p. 412-4.

- 1 2 3 4 Dubois, Sylvia and Barbara Horvath (2004). "Cajun Vernacular English: phonology." In Bernd Kortmann and Edgar W. Schneider (Ed). A Handbook of Varieties of English: A Multimedia Reference Tool. New York: Mouton de Gruyter. p. 409-10.

- ↑ Alvarez, Louis (director) (1985). Yeah You Rite! (Short documentary film). USA: Center for New American Media.

- ↑ "neutral ground". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language: Fourth Edition. 2000. Retrieved 2008-09-08.

- ↑ "banquette". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language: Fourth Edition. 2000. Retrieved 2008-09-15.

- ↑ Thomas (2006:4)

- ↑ Thomas (2006:6)

- 1 2 http://www4.uwm.edu/FLL/linguistics/dialect/staticmaps/states.html

- ↑ Harvard Dialect Survey - word use: a group of two or more people.

- ↑ Hazen, Kirk and Fluharty, Ellen. "Linguistic Diversity in the South: Changing Codes, Practices and Ideology". Page 59. Georgia University Press; 1st Edition: 2004. ISBN .0-8203-2586-4

- ↑ Regional Note from The Free Dictionary

- ↑ Thomas (2006:19)

- ↑ Lanehart, Sonja L. (editor) (2001). Sociocultural and Historical Contexts of African American English. John Benjamins Publishing. pp. 113-114.

- ↑ Thomas (2006:19-20)

- ↑ Thomas (2006:4)

- ↑ Thomas (2006:4)

Sources

- Bernstein, Cynthia (2003). "Grammatical features of southern speech". In Stephen J. Nagel; Sara L. Sanders. English in the Southern United States. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-82264-5.

- Crystal, David (2000). The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-82348-X.

- Cukor-Avila, Patricia (2003). "The complex grammatical history of African-American and white vernaculars in the South". In In Stephen J. Nagel and Sara L. Sanders. English in the Southern United States. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-82264-5.

- Labov, William; Ash, Sharon; Boberg, Charles (2006), The Atlas of North American English, Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, ISBN 3-11-016746-8

- Hazen, Kirk & Fluharty, Ellen (2004). "Defining Appalachian English". In Bender, Margaret. Linguistic Diversity in the South. Athens: University of Georgia Press. ISBN 0-8203-2586-4.

- Wolfram, Walt; Schilling-Estes, Natalie (2004), American English (Second ed.), Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing

- Thomas, Erik R. (2003), "Rural White Southern Accents" (PDF), Atlas of North American English (online), Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 1–37. [Later published as a chapter in: Bernd Kortmann and Edgar W. Schneider (eds) (2004). A Handbook of Varieties of English: A Multimedia Reference Tool. New York: Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 300-324.]

External links

- "U.S. dialect map". UTA.fi.

- Beard, Robert. "Southernese". Glossary of Southernisms.

- "Southern Accent Tutorial, with Voices of Native Speakers". A Site About Nothing.

- "Southern Fried Vocab No. 10". Smarty's World. February 12, 2010.

- Guy, Yvette Richardson (Jan 22, 2010). "Great day, the things that grandparents say". The Post and Courier.