Stellarator

A stellarator is a device used to confine hot plasma with magnetic fields in order to sustain a controlled nuclear fusion reaction. It is one of the earliest controlled fusion devices, first invented by Lyman Spitzer in 1958[1] and built the next year at what later became the Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory. The name refers to the possibility of harnessing the power source of the sun, a stellar object.[2]

Stellarators were popular in the 1950s and 1960s, but the much better results from tokamak designs led to them falling from favor in the 1970s. More recently, in the 1990s, problems with the tokamak concept have led to renewed interest in the stellarator design,[3] and a number of new devices have been built. Some important modern stellarator experiments are Wendelstein 7-X in Germany, the Helically Symmetric Experiment (HSX) in the USA, and the Large Helical Device in Japan.

Description

Background

Early fusion research generally followed two major lines of study; devices that were based on momentary compression of the fusion fuel to high densities, like the pinch devices being studied primarily in the UK, and devices that used lower densities but longer confinement times, like the magnetic mirror and stellarator. In the latter systems, the key problem was confining the plasma for long times without the hottest, most valuable, particles escaping from the device.

As plasma is electrically charged, and thus subject to Lorentz force, it can be confined by an appropriate arrangement of magnetic fields. The simplest to understand is a solenoid, consisting of a helix of wire wrapped around a cylindrical support. A plasma inside the solenoid will experience a force toward a guiding center of its orbit which moves only parallel to the applied field. However, in this case the plasma would see no force along the long axis, and would rapidly flow out the ends of the solenoid and escape.

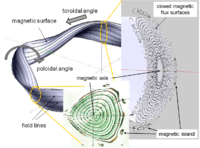

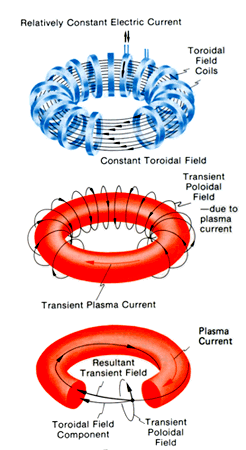

One solution to that problem is to simply bend the solenoid around into a ring, closing the ends. However, in this case the magnetic field is no longer uniform. The electrical windings on the inside edge of the toroid are closer together, and further apart on the outside edge. This leads to a weaker field on the outside than the inside. A particle's orbit will have larger curvature on the inner limb of the orbit than on the outer, leading to a net migration away from the center of the torus. These particles will eventually drift out of the confinement area.

Stellarator

Spitzer's innovation was a change in geometry. He suggested extending the torus with straight sections to form a racetrack shape, and then twisting one end by 180 degrees to produce a figure-8 shaped device. When a particle is on the outside of the center on one of the curved sections, by the time it flows through the straight area and into the other curved section it is now on the inside of the center. This means that the upward drift on one side is counteracted by the downward drift on the other.

To allow the tubes to cross without hitting, the torus sections on either end were rotated slightly, so the ends were not aligned with each other. This arrangement was less than perfect, as a particle on the inner portion at one end would not end up at the outer portion at the other, but at some other point rotated from the perfect location due to the tilt of the two ends. As a result, the stellarator is not "perfect" in terms of canceling out the drift, but the net result is to so greatly reduce drift that long confinement times appeared possible.

Newer designs

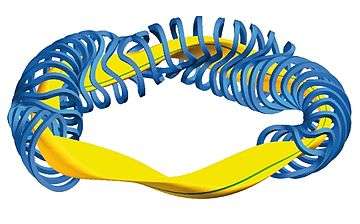

The basic idea of the stellarator is to use areas of differing magnetic fields to cancel out the net forces on a particle as it travels around the confinement area. Spitzer's concept used the mechanical arrangement of the confinement area to achieve this goal, while more modern systems use a variety of mechanical shapes or magnets to the same end. A common arrangement uses a series of coils arranged in a helix around the toroid, creating an electrical analog of the mechanical layout.

In contrast, pinch devices and the tokamak rely solely on magnetic fields for confinement, but add additional confining forces to the mix by running an electric current through the plasma itself. These currents can produce powerful confining forces, but are themselves a source of instability in the plasma. As currents were ramped up during the 1980s it appeared that they might represent a serious problem to further improvements in confinement, and the all-magnetic stellarator designs saw renewed interest.

Configurations

Several different configurations of stellarator exist, including:

- Torsatron

- A stellarator with continuous helical coils. It can also have the continuous coils replaced by a number of discrete coils producing a similar field.

- Heliotron

- A stellarator in which a helical coil is used to confine the plasma, together with a pair of poloidal field coils to provide a vertical field. Toroidal field coils can also be used to control the magnetic surface characteristics. The Large Helical Device in Japan uses this configuration.

- Modular stellarator

- A stellarator with a set of modular (separated) coils and a twisted toroidal coil.[4] e.g. Helically Symmetric Experiment (HSX) (and Helias (below))

- Heliac

- A helical axis stellarator, in which the magnetic axis (and plasma) follows a helical path to form a toroidal helix rather than a simple ring shape. The twisted plasma induces twist in the magnetic field lines to effect drift cancellation, and typically can provide more twist than the Torsatron or Heliotron, especially near the centre of the plasma (magnetic axis). The original Heliac consists only of circular coils, and the flexible heliac[5] (H-1NF, TJ-II, TU-Heliac) adds a small helical coil to allow the twist to be varied by a factor of up to 2.

- Helias

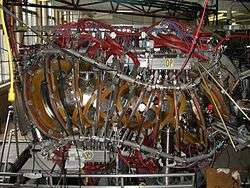

- A helical advanced stellarator, using an optimized modular coil set designed to simultaneously achieve high plasma, low Pfirsch-Schluter currents and good confinement of energetic particles; i.e., alpha particles for reactor scenarios.[6] The Helias has been proposed to be the most promising stellarator concept for a power plant, with a modular engineering design and optimised plasma, MHD and magnetic field properties. The Wendelstein 7-X device is based on a five field-period Helias configuration.

Comparison to tokamaks

The tokamak provides the required twist to the magnetic field lines not by manipulating the field with external currents, but by driving a current through the plasma itself. The field lines around the plasma current combine with the toroidal field to produce helical field lines, which wrap around the torus in both directions.

Although they also have a toroidal magnetic field topology, stellarators are distinct from tokamaks in that they are not azimuthally symmetric. They have instead a discrete rotational symmetry, often fivefold, like a regular pentagon.

It is generally argued that the development of stellarators is less advanced than tokamaks, although the intrinsic stability they provide has been sufficient for active development of this concept.

The three-dimensional nature of the field, the plasma, and the vessel make it much more difficult to do either theoretical or experimental diagnostics with stellarators. It is much harder to design a divertor (the section of the wall that receives the exhaust power from the plasma) in a stellarator, the out-of-plane magnetic coils (common in many modern stellarators and possibly all future ones) are much harder to manufacture than the simple, planar coils which suffice for a tokamak, and the utilization of the magnetic field volume and strength is generally poorer than in tokamaks.

However, stellarators, unlike tokamaks, do not require a toroidal current, so that the expense and complexity of current drive and/or the loss of availability and periodic stresses of pulsed operation can be avoided, and there is no risk of toroidal current disruptions. It might be possible to use these additional degrees of design freedom to optimize a stellarator in ways that are not possible with tokamaks.

Recent results

Optimization to reduce transport losses

The goal of magnetic confinement devices is to minimise energy transport across a magnetic field. Toroidal devices are relatively successful because the magnetic properties seen by the particles are averaged as they travel around the torus. The strength of the field seen by a particle, however, generally varies, so that some particles will be trapped by the mirror effect. These particles will not be able to average the magnetic properties so effectively, which will result in increased energy transport. In most stellarators, these changes in field strength are greater than in tokamaks, which is a major reason that transport in stellarators tends to be higher than in tokamaks.

University of Wisconsin electrical engineering Professor David Anderson and research assistant John Canik proved in 2007 that the Helically Symmetric eXperiment (HSX) can overcome this major barrier in plasma research. The HSX is the first stellarator to use a quasisymmetric magnetic field. The team designed and built the HSX with the prediction that quasisymmetry would reduce energy transport. As the team's latest research showed, that is exactly what it does. "This is the first demonstration that quasisymmetry works, and you can actually measure the reduction in transport that you get," says Canik. [7] [8]

The newer Wendelstein 7-X in Germany was designed to be close to omnigeneity (a property of the magnetic field such that the mean radial drift is zero), which is a necessary but not sufficient condition for quasisymmetry;[9] that is, all quasisymmetric magnetic fields are omnigenous, but not all omnigenous magnetic fields are quasisymmetric.

See also

References

- ↑ Lyman Spitzer Jr. (1958). "The Stellarator Concept". The Physics of Fluids. 1 (4): 253. doi:10.1063/1.1705883.

- ↑ Daniel Clery (2015). "The bizarre reactor that might save nuclear fusion". Science. doi:10.1126/science.aad4746.

- ↑ "After ITER, Many Other Obstacles for Fusion Power". Science. January 17, 2013.

- ↑ Wakatani, M. (1998). Stellarator and Heliotron Devices. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-507831-4.

- ↑ Harris, J. H.; Cantrell, J. L.; Hender, T. C.; Carreras, B. A.; Morris, R. N. (1985). "A flexible heliac configuration". Nuc. Fusion. 25 (5): 623. doi:10.1088/0029-5515/25/5/005.

- ↑ Basics of Helias-type Stellarators at the Wayback Machine (archived 21 June 2013)

- ↑ Canik, J. M.; et al. (23 February 2007). "Experimental Demonstration of Improved Neoclassical Transport with Quasihelical Symmetry". Physical Review Letters. 98 (8): 085002. Bibcode:2007PhRvL..98h5002C. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.98.085002. PMID 17359105.

- ↑ New stellerator a step forward in plasma research (news article on phys.org)

- ↑ "Omnigeneity - FusionWiki". fusionwiki.ciemat.es. Retrieved 2016-01-31.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Stellarators. |

- Stellarator News from ORNL

- Stellarators Around the World - inc UST-2

- Spherical Stellarator

- Low-cost Stellarator