Tala (music)

| Hindustani classical music | |

|---|---|

| Concepts | |

| Instruments | |

|

melody: Vocals • Sitar • Sarod • Surbahar • Rudra veena • Violin • Sarangi • Esraj/Dilruba • Bansuri • Shehnai • Santoor • Harmonium • Jal tarang drone: Tanpura • Shruti box • Swarmandal | |

| Genres | |

|

classical: Dhrupad • Dhamar • Khyal • Tarana • Sadra semiclassical: Thumri • Dadra • Qawwali • Ghazal • Chaiti • Kajri | |

| Thaats | |

|

Bilaval • Khamaj • Kafi • Asavari • Bhairav • Bhairavi • Todi • Purvi • Marwa • Kalyan |

Taala, Taal or Taalantainmah (Sanskrit tāla, literally a "clap"), is the term used in Indian classical music for the rhythmic pattern of any composition and for the entire subject of rhythm, roughly corresponding to metre in Western music, though closer conceptual equivalents are to be found in the older system of rhythmic mode and its relations with the "foot" of classical poetry, or with other Asian classical systems such as the notion of usul in the theory of Ottoman/Turkish music.

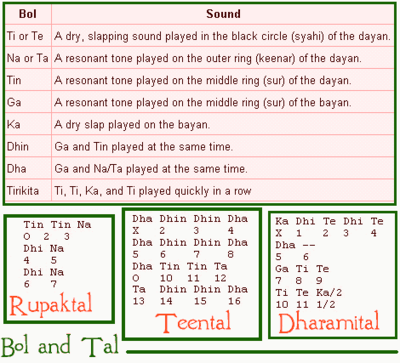

A tala is a regular, repeating rhythmic phrase, particularly as rendered on a percussive instrument with an ebb and flow of various intonations represented as a theka, a sequence of drum-syllables or bol. Indian classical music, both northern and southern, has complex, all-embracing rules for the elaboration of possible patterns and each such pattern has its own name, though in practice a few talas are very common while others are rare. The most common instrument for keeping rhythm in Hindustani music is the tabla (also transliterated as Tabala), while in Carnatic music it is the mridangam (also transliterated as mridang). Some of commonly attributing tala or more often boles of theka are as follow; "char matra" (dhin dha teen na) "chaau matra" (dha dhi na dha tee na) "saat matra" (ten ten na dhin na dhin na) "aath matra" (dha ge na te na ka dhi nee) and many more such matras are formed .

Terminology

Each repeated cycle of a tala is called an avartan. This is counted additively in sections (vibhag or anga) which roughly correspond to bars or measures but may not have the same number of beats (matra, akshara) and may be marked by accents or rests. So the Hindustani Jhoomra tal has 14 beats, counted 3+4+3+4, which differs from Dhamar tal, also of 14 beats but counted 5+2+3+4. The spacing of the vibhag accents makes them distinct, otherwise, again, since Rupak tal consists of 7 beats, two cycles of it of would be indistinguishable from one cycle of the related Dhamar tal.[1] However the most common Hindustani tala, Teental, is a regularly-divisible cycle of four measures of four beats each.

The first beat of any tala, called sam (pronounced as the English word 'sum' and meaning even or equal, archaically meaning nil) is always the most important and heavily emphasised. It is the point of resolution in the rhythm where the percussionist's and soloist's phrases culminate: a soloist has to sound an important note of the raga there, and a North Indian classical dance composition must end there. However, melodies do not always begin on the first beat of the tala but may be offset, for example to suit the words of a composition so that the most accented word falls upon the sam. The term talli, literally "shift", is used to describe this offset in Tamil. A composition may also start with an anacrusis on one of the last beats of the previous cycle of the tala, called ateeta eduppu in Tamil.

The tāla is indicated visually by using a series of rhythmic hand gestures called kriyas that correspond to the angas or "limbs", or vibhag of the tāla. These movements define the tala in Carnatic music, and in the Hindustani tradition too, when learning and reciting the tala, the first beat of any vibhag is known as tali ("clap") and is accompanied by a clap of the hands, while an "empty" (khali) vibhag is indicated with a sideways wave of the dominant clapping hand (usually the right) or the placing of the back of the hand upon the base hand's palm instead. But northern definitions of tala rely far more upon specific drum-strokes, known as bols, each with its own name that can be vocalized as well as written. In one common notation the sam is denoted by an 'X' and the khali, which is always the first beat of a particular vibhag, denoted by '0' (zero).[2]

A tala does not have a fixed tempo (laya) and can be played at different speeds. In Hindustani classical music a typical recital of a raga falls into two or three parts categorized by the quickening tempo of the music; Vilambit (delayed, i.e., slow), Madhya (medium tempo) and Drut (fast). Carnatic music adds an extra slow and fast category, categorised by divisions of the pulse; Chauka (1 stroke per beat), Vilamba (2 strokes per beat), Madhyama (4 strokes per beat), Dhuridha (8 strokes per beat) and lastly Adi-dhuridha (16 strokes per beat).

Tāla in Carnatic music

Carnatic music uses various classification systems of tālas such as the Chapu (4 talas), Chanda (108 talas) and Melakarta (72 talas). The Suladi Sapta Tāla system (35 talas) is used here, according to which there are seven families of tāla. A tāla cannot exist without reference to one of five jatis, differentiated by the length in beats of the laghu, thus allowing thirty-five possible tālas. With all possible combinations of tala types and laghu lengths, there are 5 x 7 = 35 talas having lengths ranging from 3 (Tisra-jati Eka tala) to 29 (sankeerna jati dhruva tala) aksharas. The seven tala families and the number of aksharas for each of the 35 talas are;

| Tala | Anga Notation | Tisra (3) | Chatusra (4) | Khanda (5) | Misra (7) | Sankeerna (9) |

| Dhruva | lOll | 11 | 14 | 17 | 23 | 29 |

| Matya | lOl | 8 | 10 | 12 | 16 | 20 |

| Rupaka | Ol | 5 | 6 | 7 | 9 | 11 |

| Jhampa | lUO | 6 | 7 | 8 | 10 | 12 |

| Triputa | lOO | 7 | 8 | 9 | 11 | 13 |

| Ata | llOO | 10 | 12 | 14 | 18 | 22 |

| Eka | l | 3 | 4 | 5 | 7 | 9 |

In practice, only a few talas have compositions set to them. The most common tala is Chaturasra-nadai Chaturasra-jaati Triputa tala, also called Adi tala (Adi meaning primordial in Sanskrit). Nadai is a term which means subdivision of beats. Many kritis and around half of the varnams are set to this tala. Other common talas include:

- Chaturasra-nadai Chaturasra-jaati Rupaka tala (or simply Rupaka tala).[3] A large body of krtis is set to this tala.

- Khanda Chapu (a 10-count) and Misra Chapu (a 14-count), both of which do not fit very well into the suladi sapta tala scheme. Many padams are set to Misra Chapu, while there are also krtis set to both the above talas.

- Chatusra-nadai Khanda-jati Ata tala (or simply Ata tala).[3] Around half of the varnams are set to this tala.

- Tisra-nadai Chatusra-jati Triputa tala (Adi Tala Tisra-Nadai).[3] A few fast-paced kritis are set to this tala. As this tala is a twenty-four beat cycle, compositions in it can be and sometimes are sung in Rupaka talam.

Strokes in tāla

The Suladi Saptha Tāla system uses three of six possible angas in different arrangements;

- Anudhrutam, a single beat, notated 'U', a downward clap of the open hand with the palm facing down.

- Dhrutam, a pattern of 2 beats, notated 'O', a downward clap with the palm facing down followed by a second downward clap with the palm facing up.

- Laghu, a pattern with a variable number of beats, 3, 4, 5, 7 or 9, depending on the jati. It is notated 'l' and consists of a downward clap with the palm facing down followed by counting from little finger to thumb and back, depending on the jati.

Jatis

Each taal can incorporate one of five jatis. (For convenience, the term 'tāla' is commonly used to denote the tāla-jati.) Each tala family has a default jati associated with it; the tala name mentioned without qualification refers to the default jati;

- Dhruva tala is by default chaturasra jati

- Matya tala is chaturasra jati

- Rupaka tala is chaturasra jati

- Jhampa tala is misra jati[3]

- Triputa tala is chaturasra jati (like this, it is also known as Adi tala)

- Ata tala is kanda jati

- Eka tala is chaturasra jati

| Jati | Number of Aksharas |

| Chaturasra | 4 |

| Thisra | 3 |

| Khanda | 5 |

| Misra | 7 |

| Sankeerna | 9 |

For example, one cycle of khanda-jati rupaka tala comprises a 2-beat dhrutam followed by a 5-beat laghu. The cycle is, thus, 7 aksharas long. Chaturasra nadai khanda-jati Rupaka tala has 7 aksharam, each of which is 4 matras long; each avartana of the tala is 4 x 7 = 28 matras long. For Misra nadai Khanda-jati Rupaka tala, it would be 7 x 7 = 49 matra.

Gati (nadai in Tamil, nadaka in Telugu, nade in Kannada)

The number of maatras in an akshara is called the nadai. This number can be 3, 4, 5, 7 or 9, and take the same name as the jatis. The default nadai is Chatusram:

| Gati | Maatras | Phonetic representation of beats | |

| Tisra | 3 | Tha Ki Ta | |

| Chatusra | 4 | Tha Ka Dhi Mi | |

| Khanda | 5 | Tha Ka Tha Ki Ta | |

| Misra | 7 | Tha Ki Ta Tha Ka Dhi Mi | |

| Sankeerna | 9 | Tha Ka Dhi Mi Tha Ka Tha Ki Ta |

Sometimes, pallavis are sung as part of a Ragam Thanam Pallavi exposition in some of the rarer, more complicated talas; such pallavis, if sung in a non-Chatusra-nadai tala, are called nadai pallavis. In addition, pallavis are often sung in chauka kale(slowing the tala cycle by a magnitude of four times), although this trend seems to be slowing.

Tala in Hindustani music

Talas have a vocalised and therefore recordable form wherein individual beats are expressed as phonetic representations of various strokes played upon the tabla. Various Gharanas (literally "Houses" which can be inferred to be "styles" - basically styles of the same art with cultivated traditional variances) also have their own preferences. For example, the Kirana Gharana uses Ektaal more frequently for Vilambit Khayal while the Jaipur Gharana uses Trital. Jaipur Gharana is also known to use Ada Trital, a variation of Trital for transitioning from Vilambit to Drut laey.

The Khyal vibhag has no beats on the bayan, i.e. no bass beats this can be seen as a way to enforce the balance between the usage of heavy (bass dominated) and fine (treble) beats or more simply it can be thought of another mnemonic to keep track of the rhythmic cycle (in addition to Sam). The khali is played with a stressed syllable that can easily be picked out from the surrounding beats.

Some rare talas even contain a "half-beat". For example, Dharami is an 11 1/2 beat cycle where the final "Ka" only occupies half the time of the other beats. This tala's 6th beat does not have a played syllable - in western terms it is a "rest".

Common Hindustani talas

Some talas, for example Dhamaar, Ek, Jhoomra and Chau talas, lend themselves better to slow and medium tempos. Others flourish at faster speeds, like Jhap or Rupak talas. Trital or Teental is one of the most popular, since it is as aesthetic at slower tempos as it is at faster speeds.

There are many taals in Hindustani music, some of the more popular ones are:

| Name | Beats | Division | Vibhaga |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tintal (or Trital or Teental) | 16 | 4+4+4+4 | X 2 0 3 |

| Jhoomra | 14 | 3+4+3+4 | X 2 0 3 |

| Tilwada | 16 | 4+4+4+4 | X 2 0 3 |

| Dhamar | 14 | 5+2+3+4 | X 2 0 3 |

| Ektal and Chautal | 12 | 2+2+2+2+2+2 | X 0 2 0 3 4 |

| Jhaptal | 10 | 2+3+2+3 | X 2 0 3 |

| Keherwa | 8 | 4+4 | X 0 |

| Rupak (Mughlai/Roopak) | 7 | 3+2+2 | X 2 3 |

| Dadra | 6 | 3+3 | X 0 |

Change of rhythm/Taal Mala:- Change of rhythm/Taal Mala is that in a raaga every line has different Taal i.e. starting of raaga from 10 matras, next line 12 matras, other lines has 14/16 matras. Taals are increased in ascending orders in Taal Mala. The doubling/tripling of the raaga in Taal Mala will be increased in ascending orders. As raaga has matras like as 10,12,14,16. when a singer does doubling (dogun) of the raagas in increasing/ascending orders i.e. 18,20,22,24....If taal mala is sung in even, change of rhythm will be increased in even numbers only and likewise for odd also. It is also mentioned in Gurmat Gyan Group, Raag Ratan, Taal Ank.

Additional talas

Rarer Hindustani talas

| Name | Beats | Division | Vibhaga |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adachoutal | 14 | 2+2+2+2+2+2+2 | X 2 0 3 0 4 0 |

| Brahmtal | 28 | 2+2+2+2+2+2+2+2+2+2+2+2+2+2 | X 0 2 3 0 4 5 6 0 7 8 9 10 0 |

| Dipchandi | 14 | 3+4+3+4 | X 2 0 3 |

| Shikar | 17 | 6+6+2+3 | X 0 3 4 |

| Sultal | 10 | 2+2+2+2+2 | x 0 2 3 0 |

| Ussole e Fakhta | 5 | 1+1+1+1+1 | x 3 |

| Farodast | 14 | 3+4+3+4 | X 2 0 3 |

Rarer Carnatic talas

Other than these 35 talas there are 108 so-called anga talas. The following is the exhaustive pattern of beats used in constructing them.

| Anga | Symbol | Aksharakala | Mode of Counting |

| Anudrutam | U | 1 | 1beat |

| Druta | O | 2 | 1 beat + Visarijitam (wave of hand) |

| Druta-virama | (OU) | 3 | |

| Laghu (Chatusra-jati) | l | 4 | 1 beat + 3 finger count |

| Laghu-virama | U) | 5 | |

| Laghu-druta | O) | 6 | |

| Laghu-druta-virama | OU) | 7 | |

| Guru | 8 | 8 | A beat followed by circular movement of the right hand in the clockwise direction with closed fingers. |

| Guru-virama | (8U) | 9 | |

| Guru-druta | (8O) | 10 | |

| Guru-druta-virama | (8OU) | 11 | |

| Plutam | ) | 12 | 1 beat + kryshya (waving the right hand from right to left) + 1 sarpini (waving the right hand from left to right) - each of 4 aksharakalas OR a Guru followed by the hand waving downwards |

| Pluta-virana | U) | 13 | |

| Pluta-druta | O) | 14 | |

| Pluta-druta-virama | OU) | 15 | |

| Kakapadam | + | 16 | 1 beat + patakam (lifting the right hand) + kryshya + sarpini - each of 4 aksharakalas) |

Compositions are rare in these lengthy talas. They are mostly used in performing the Pallavi of Ragam Thanam Pallavis. Some examples of anga talas are:

Sarabhanandana tala

| 8 | O | l | l | O | U | U) | |

| O | O | O | U | O) | OU) | U) | O |

| U | O | U | O | U) | O | (OU) | O) |

Simhanandana tala : It is the longest tala.

| 8 | 8 | l | ) | l | 8 | O | O |

| 8 | 8 | l | ) | l | ) | 8 | l |

| l | + |

Another type of tala is the chhanda tala. These are talas set to the lyrics of the Thirupugazh by the Tamil composer Arunagirinathar. He is said to have written 16000 hyms each in a different chhanda tala. Of these, only 1500-2000 are available.

See also

Notes

- 1 2 Kaufmann(1968)

- ↑ Chandrakantha Music of India http://chandrakantha.com/faq/tala_thalam.html

- 1 2 3 4 A practical course in Karnatik music by Prof. P. Sambamurthy, Book II, The Indian Music Publishing House, Madras

References

- Oxford Journals: A Study in East Indian Rhythm, Sargeant and Lahiri, Musical Quarterly.1931; XVII: 427-438

- Ancient Traditions—Future Possibilities: Rhythmic Training Through the Traditions of Africa, Bali and India, Author: Matthew Montfort, Mill Valley: Panoramic Press, 1985. ISBN 0-937879-00-2 (Spiral Bound Book)

- Humble, M (2002): The Development of Rhythmic Organization in Indian Classical Music, MA dissertation, School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London.

- Manfred Junius: Die Tālas der nordindischen Musik (The Talas of North Indian Music), München (Munich), Salzburg: Katzbichler, 1983.

- Kaufmann, Walter (1968), The Ragas of North India, Calcutta: Oxford and IBH Publishing Company.

External links

- A Visual Introduction to Rhythms (taal) in Hindustani Classical Music

- Colvin Russell: Tala Primer - A basic introduction to tabla and tala.

- KKSongs Talamala: Recordings of Tabla Bols, database for Hindustani Talas.

- Ancient Future: MIDI files of the common (major) Hindustani Talas.

- Basics of Hindustani Classical Music for Listeners: a downloadable PDF, and an online video talk. Includes "What is Taal"? and the difference between a Taal and a Theka.

| Indian classical music |

|---|

| Concepts |