The Blacker the Berry (novel)

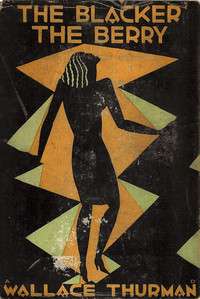

Dust jacket by Aaron Douglas | |

| Author | Wallace Thurman |

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre | African-American Literature |

| Publisher | The Macaulay Company |

Publication date | 1929 |

| Media type | Print Hardcover |

| Pages | 254 |

The Blacker the Berry: A Novel of Negro Life (1929) is a novel by American author Wallace Thurman, associated with the Harlem Renaissance. It was considered groundbreaking for its exploration of colorism and racial discrimination within the black community, where lighter skin was often favored, especially for women.

The novel tells the story of Emma Lou Morgan, a young black woman with dark skin. It begins in Boise, Idaho and follows Emma Lou in her journey to college at USC and a move to Harlem, New York City for work. Set during the Harlem Renaissance, the novel explores Emma Lou's experiences with colorism, discrimination by lighter-skinned African Americans due to her dark skin. She learns to come to terms with her skin color in order to find satisfaction in her life.

Plot summary

- Part 1 Emma Lou

Born in Boise, Idaho, Emma Lou Morgan is an African-American girl who has extremely dark skin. Her mother's family have lighter skin that shows European ancestry; the "blue-black" hue came from her father, who left her and her mother soon after her birth. Believing that her color will reduce her marriageability, her mother's people try to help her lighten her skin with bleaching and commercially available creams, but nothing works. When her mother says "a black boy could get along but a black girl would never know anything but sorrow and disappointment," [1] Emma Lou wishes she had been a boy. The only "Negro pupil in the entire school," she feels extra conspicuous at graduation amongst the white faces and white robes.

Emma Lou's Uncle Joe encourages her to go to the University of Southern California (USC), where she'll be among black students, and he encourages her to study education and move South to teach. He believes that smaller towns like Boise "encouraged stupid color prejudice such as she encountered among the blue vein circle in her home town."[1] Emma Lou’s maternal grandmother was closely associated with the "blue veins", black people whose skin was light enough to show veins. Uncle Joe thought life would be better for Emma Lou in Los Angeles, where people had more to think about.

At USC, Emma Lou intends to meet the "right" crowd among other Negro students. On registration day she meets a black girl named Hazel Mason; unfortunately, when she speaks Emma Lou decides that she is the wrong sort, definitely lower-class. Other girls, though pleasant, never invite her into their circles or sorority, especially when they recognize that they've seen her with Hazel, whose "minstrel" demeanor is not good for the black image. When Hazel drops out of school, Grace Giles become Emma Lou's friend but informs her that the sorority only accepts wealthy, light-skinned girls. Emma Lou begins to notice that black leaders tend to have light skin or light-skinned wives. By summer vacation, she feels more trapped by her skin.

Back in Boise, Emma Lou meets Weldon Taylor at a picnic. Although darker than her ideal, he attracts her, and she ends up going too far with him that night, thinking she is in love. Over the next two weeks, she is thrilled to be with Taylor, for "his presence and his love making."[1] He had been to college but temporarily dropped out to build up his tuition fund, traveling from town to town, finding work and a new girl each time. When he announced that he was leaving Boise to become a Pullman porter, Emma Lou blamed her color. She puts in the rest of her college time, then moves to New York City to find work—and hopefully, a better life.

- Part 2 Harlem

In Harlem, Emma Lou meets a young man named John whom she decides is "too dark." She heads to an employment agency seeking work as a stenographer; lacking experience, she pads her account of her skills. She is sent to a real-estate office for an interview, only to be told that they have someone else in mind. She returns to the agency and the manager, Mrs. Blake, invites her to lunch, and Emma Lou is "warmed toward any suggestion of friendliness" and excited to have the chance "to make a welcome contact."[1]

Mrs. Blake tells her about work prospects, saying that black businessmen preferred to hire light-skinned, pretty girls; she advises Emma Lou to go to Columbia Teachers' College and train for a job in the public-school system. After lunch, Emma is walking on Seventh Avenue and while stopping to check her reflection, she notices a few young black men nearby and hears one comment, "There’s a girl for you ‘Fats’", to which the reply is: "Man, you know I don’t haul no coal."[1]

- Part 3 Alva

Determined to stay in New York, Emma Lou finds a job as a maid to Arline Strange, an actress "in an alleged melodrama about Negro life in Harlem."[1] She thinks all the characters are caricatures. Arline and her brother from Chicago take Emma Lou to her first cabaret one night, where he makes her a drink from his hip flask. Emma Lou, entranced by the dancing, gets to be part of it when a man from another table, Alva, invites her. When the lights go up, he returns her to sit with Arline and her brother. The next morning, Alva and his roommate Braxton discuss the previous evening, agreeing that Alva did Emma Lou a favor in dancing with her.

Intrigued by the cabaret, Emma Lou talks to the stage director about being in the dance chorus. He tells her plainly the girls are chosen in part for appearance, and notes they all have lighter skin than hers. She decides to look for a new place to live, hoping to meet "the right sort of people."[1]

One evening she goes to a casino, where she recognizes Alva. When she approaches him and asks if he remembers her, he politely acts like he does: he talks to her, dances with her, and even gives her his phone number. She calls him a couple of times before they make plans. Braxton is critical of Alva's seeing her, but he thinks, "She’s just as good as the rest, and you know what they say, ‘The Blacker the berry, the sweeter the juice.’"[1]

- Part 4 Rent Party

After avoiding taking Emma Lou to parties or dances, not wanting his friends to meet her (preferring to be seen with light-skinned Geraldine), Alva finally takes her to a "rent party. Used to manipulating young women for money, Alva liked Geraldine for herself. Emma Lou was very excited about the party, and worried that she would encounter more discrimination. Once there, they happened on to a conversation revolving around race: the differences between being a mulatto and a Negro, and individuals who are prejudiced or "color struck."[1]

At the rent party, Emma had consumed more alcohol than usual, and the next morning her landlady demands that she find somewhere else to stay. As the woman speaks, Emma Lou remembers a little more about Alva bringing her home after the party and realizes that the woman might be right that her behavior hadn't met the boardinghouse's respectable standards. Emma Lou thought more about Alva, who seemed kinder than others in her life, but she was aware of his manipulation.

Alva has his own trouble with Braxton: he has no job and pays no rent. When Braxton finally moves out, Alva doesn't want Emma Lou to move in. One night the couple goes to a theatre, but Emma Lou doesn't have a good time: "You’re always taking me some place, or placing me in some position where I’ll be insulted."[1] One night, after an argument with Emma Lou, Alva returns to his room to find Geraldine sleeping in his bed; when she wakens, she announces that she's pregnant by him.

- Part 5 Pyrrhic Victory

Two years later, Emma Lou works as a personal maid/companion to Clere Sloane, a retired actress married to Campbell Kitchen, a white writer very interested in Harlem. He encouraged Emma Lou to seek more education in order to achieve economic independence. She has few friends and still feels very out-of-place. When she tries to see Alva after they had stopped seeing each other for a time, Geraldine answers the door and Emma Lou leaves without comment.

Geraldine and Alva's son has been born disfigured and possibly retarded and seems to bring them endless trouble; they often wish he would die. Geraldine blames Alva—another man would have made a better baby—and her mother blames both of them for not bothering to marry before his birth (or conception). Alva has become a money-wasting alcoholic; Geraldine works hard, trying to build up an escape fund.

Having moved to the Y.W.C.A., Emma Lou has found some new friends and is studying teaching. She continues to work hard but to feel no better about her appearance, although her friend Gwendolyn Johnson tries to help her. She starts seeing Benson Brown, a light-skinned man described as a "yaller nigger."[1] His appearance seems reason enough to see him. But when she learns that Geraldine had abandoned Alva and their son, she goes to check on them and he soon he has her talking care of little Alva Jr. After 6 months, she begins teaching at a Harlem public school, wearing lots of dark-skin-concealing makeup but being teased for it by colleagues. She nurtures the child better than his parents ever did, but she and Alva have a rocky relationship.

As Emma Lou gains more economic independence, she discovers that it isn't everything; she's still not happy. She decides to leave Alva and his son. When she returns to the Y.W.C.A. she contacts Benson, who announces that he and Gwendolyn have been dating and have decided to marry. They even invite her to the wedding.

Emma Lou realizes she has spent her life running: she ran from Boise's color prejudice; she left Los Angeles for similar reasons. But she decides never to run again. She knows there are many people like her and that she has to accept herself.[1]

Characters

- Emma Lou Morgan: a young African-American woman. Growing up in Boise, Idaho, she encounters discrimination by lighter-skinned blacks among her family and community. She takes after her father in appearance, who abandoned her and her lighter-skinned mother.

- Uncle Joe: Emma Lou is closer to him than others in her mother's family; she follows his advice to go to Los Angeles for college.

- Weldon Taylor: Back in Boise, Emma Lou meets Weldon Taylor at a picnic. He is darker skinned, and she sleeps with him and thinks she is in love. He leaves to become a Pullman porter, and Emma Lou mistakingly blames him leaving because of her color.

- Hazel Mason: The first black student whom Emma Lou meets at USC. Judging her to be the "wrong" kind of Negro, Emma tries to limit their association.

- Alva: one of Emma Lou’s love interests in Harlem. He is a lighter-skinned man who manipulates women to use their money to get by. Married twice already, he has become alcoholic.

- Braxton: Alva’s roommate. He does not approve of Alva's seeing Emma Lou because of her skin color.

- Geraldine: one of Alva’s companions; she bears his son, who is born disfigured. She abandons them both.

- John: Emma Lou’s first love interest in Harlem.

- Arline Strange: an actress. Emma Lou works as her maid, helping with make-up and costumes.

- Gwendolyn Johnson: Emma Lou’s friend from the Y.W.C.A. She eventually marries Benson Brown, whom Emma Lou had dated.

- Benson Brown: a man Emma Lou meets after she moves to the Y.W.C.A. He is lighter-skinned and promising, the "right" sort of African-American man.[1]

Influence

Thurman's novel has been widely discussed. Through Emma Lou Morgan, he expressed the idea that dark skin presented more problems for a woman than a man. The young woman struggles with people's reactions to her.

Variations in skin tone has historically related to European and Native American ancestry among African Americans, and the tangled history of slave societies, and benefits that some mixed-race children received from white fathers. The topic of behavior related to differing skin tones has since been treated by other artists and writers, and the issue of skin bias has been studied as a sociological and psychological issue among academics.[2]

Despite the calls for Black Power and "Black is beautiful" in the mid-twentieth century, studies have found that skin tone bias continues. It is more openly discussed, studied and, at times, mocked.[2] The director Spike Lee has explored this topic, particularly in his film School Daze (1988), about students at a prestigious college (modeled on Spelman College and Morehouse College).

In 2001 Maxine S. Thompson and Verna M. Keith presented the results of a study on gender, skin tone and self efficacy. They found darker skin more problematic for women, for whom skin tone had more effect on self-esteem, especially for lower and working class women. Higher class women could escape the effects of skin color by other accomplishments. Skin tone presented less of a self-esteem issue for men, but did affect their sense of self-efficacy.[2]

In 2004 Daniel Scott III published an article noting that Thurman was interested in Harlem in the 1920s as a place for personal transformation. He was aware that people were attracted there from all over the United States, and brought expectations with them. The experience of living there opened them to new possibilities, which he expressed in his first novel. People were stimulated by meeting many new strangers, and by opportunities afforded by clubs, cabarets, concert halls, theatres and other venues.[3]

The novel's line "the blacker the berry, the sweeter the juice" is referenced in Tupac Shakur's 1993 song Keep Ya Head Up, as well as Pharoahe Monch's 2007 song Let's Go. Kendrick Lamar's 2015 song The Blacker the Berry is named for the novel.

See also

- Harlem Renaissance

- Wallace Thurman

- African-American literature

- Encyclopedia of the Harlem Renaissance

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Thurman , Wallace. The Blacker the Berry. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, Inc., 2008.

- 1 2 3 Thompson, Maxine S.; Keith, Verna M. (2001). "The Blacker the Berry: Gender, Skin Tone, Self-Esteem, and Self-Efficacy". Gender and Society. 15 (3): 336–357. doi:10.1177/089124301015003002.

- ↑ Scott, Daniel M. (2004). "Harlem Shadows: Re-Evaluating Wallace Thurman's The Blacker the Berry". MELUS. 29 (3/4): 323–339. JSTOR 4141858.

Further reading

- Crawford, Margo Natalie. Dilution Anxiety and the Black Phallus, Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 2008.

- Durr, Marlese, and Shirley A. Hill, editors, Race, Work, and Family in the Lives of African Americans, Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, 2006.

- Farebrother, Rachel. The Collage Aesthetic in the Harlem Renaissance, Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2009.

- Macon, Wanda Celeste. Adolescent Characters' Sexual Behavior in Selected Fiction of Six Twentieth Century African American Authors, 1992.

- Ogbar, Jeffrey O.G. The Harlem Renaissance Revisited: Politics, Arts, and Letters, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010.

- Tarver, Australia, and Paula C Barnes, Eds. New Voices on the Harlem Renaissance: Essays on Race, Gender, and Literary Discourse', Madison, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 2006.