The Greatest Story Ever Told

| The Greatest Story Ever Told | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | George Stevens |

| Produced by | George Stevens |

| Screenplay by |

James Lee Barrett George Stevens |

| Starring |

Max von Sydow Dorothy McGuire Charlton Heston Jose Ferrer Telly Savalas |

| Music by | Alfred Newman |

| Cinematography |

Loyal Griggs William C. Mellor |

| Edited by |

Harold F. Kress Argyle Nelson, Jr. Frank O'Neil |

Production company |

George Stevens Productions |

| Distributed by | United Artists |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 260 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $21 million[1] |

| Box office | $15,473,333[2] |

The Greatest Story Ever Told is a 1965 American epic film produced and directed by George Stevens. It is a retelling of the story of Jesus Christ, from the Nativity through the Resurrection. This film is notable for its large ensemble cast and for being the last film appearance of Claude Rains.

Cast

The major roles in the movie were following:

- Max von Sydow as Jesus

- Dorothy McGuire as the Virgin Mary

- Charlton Heston as John the Baptist

- Claude Rains as Herod the Great

- Jose Ferrer as Herod Antipas

- Telly Savalas as Pontius Pilate

- Martin Landau as Caiaphas

- David McCallum as Judas Iscariot

- Donald Pleasence as "The Dark Hermit" (a personification of Satan)

- Michael Anderson, Jr. as James the Just

- Roddy McDowall as Matthew

- Joanna Dunham as Mary Magdalene

- Joseph Schildkraut as Nicodemus

- Ed Wynn as "Old Aram"

Smaller roles (some only a few seconds) were played by Michael Ansara, Ina Balin, Carroll Baker, Robert Blake, Pat Boone, Victor Buono, John Considine, Richard Conte, John Crawford, Jamie Farr, David Hedison, Van Heflin, Russell Johnson, Angela Lansbury, Mark Lenard, Robert Loggia, John Lupton, Sal Mineo, Nehemiah Persoff, Sidney Poitier, Gary Raymond, Marian Seldes, David Sheiner, Abraham Sofaer, Paul Stewart, John Wayne and Shelley Winters.

Pre-production

The Greatest Story Ever Told originated as a U.S. radio series in 1947, half-hour episodes inspired by the Gospels. The series was adapted into a 1949 novel by Fulton Oursler, a senior editor at Reader's Digest.[3] Darryl F. Zanuck, the head of 20th Century Fox, acquired the film rights to the Oursler novel shortly after publication,[4] but never brought it to pre-production.[5]

In 1958, when George Stevens was producing and directing The Diary of Anne Frank at 20th Century Fox, he became aware that the studio owned the rights to the Oursler property. Stevens created a company, "The Greatest Story Productions", to film the novel.[5]

It took two years to write the screenplay. Stevens collaborated with Ivan Moffat and then with James Lee Barrett. It was the only time Stevens received screenplay credit for a film he directed.[5] Ray Bradbury and Reginald Rose were considered but neither participated. The poet Carl Sandburg was solicited though it is not certain if any of his contributions were included. Sandburg, however, did receive screen credit for "creative association."[5][6]

Financial excesses began to grow during pre-production. Stevens commissioned French artist André Girard to prepare 352 oil paintings of Biblical scenes to use as storyboards. Stevens also traveled to the Vatican to see Pope John XXIII for advice.[3]

In August 1961, 20th Century Fox withdrew from the project, noting that $2.3 million had been spent without any footage being shot. Stevens was given two years to find another studio or 20th Century Fox would reclaim its rights. Stevens moved the film to United Artists.[3]

Meanwhile, MGM proceeded with their own 1961 Technicolor epic about the life of Christ, King of Kings starring Jeffrey Hunter as Jesus. Filmed in Spain, when released, turned out to be nearly an hour shorter than The Greatest Story Ever Told.

Casting

For The Greatest Story Ever Told, Stevens cast Swedish actor Max von Sydow as Jesus. Von Sydow had never appeared in an English-language film and was best known for his performances in Ingmar Bergman's dramatic films.[7] Stevens wanted an unknown actor free of secular and unseemly associations in the mind of the public.[8]

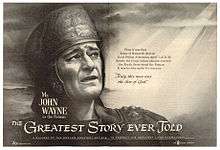

The Greatest Story Ever Told featured an ensemble of well-known actors, many of them in brief, even cameo, appearances. Some critics would later complain that the large cast distracted from the solemnity, notably in the appearance of John Wayne as the Roman centurion who comments on the Crucifixion, in his well-known voice, by stating: "Truly this man was the Son of God."[9][10]

Production

Stevens shot The Greatest Story Ever Told in the U.S. southwest, in Arizona, California, Nevada and Utah. Pyramid Lake in Nevada represented the Sea of Galilee, Lake Moab in Utah[11] was used to film the Sermon on the Mount, and California's Death Valley was the setting of Jesus' 40-day journey into the wilderness.[3][12]

Stevens explained his decision to use the U.S. rather than in the Middle East or Europe in 1962. "I wanted to get an effect of grandeur as a background to Christ, and none of the Holy Land areas shape up with the excitement of the American southwest," he said. "I know that Colorado is not the Jordan, nor is Southern Utah Palestine. But our intention is to romanticize the area, and it can be done better here."[3]

Forty-seven sets were constructed, on location and in Hollywood studios, to accommodate Stevens' vision.[13] The Jerusalem city set was built near the northwest corner of RKO Forty Acres by early 1963, and was demolished soon after filming was completed that summer.[14]

To fill location scenes with extras, Stevens turned to local sources – R.O.T.C. cadets from an Arizona high school played Roman soldiers (after 550 Navajo Indians from a nearby reservation allegedly did not give a convincing performance; other sources claim they weren't on set long enough and left early to take part in a tribal election[15])[16] and Arizona Department of Welfare provided disabled state aid recipients to play the afflicted who sought Jesus' healing.[3]

Principal photography was scheduled to run three months but ran nine months or more[17] due to numerous delays and setbacks (most of which were due to Stevens' insistence on shooting dozens of retakes in every scene).[18] Joseph Schildkraut died before completing his performance as Nicodemus, requiring scenes to be rewritten around his absence. Cinematographer William C. Mellor had a fatal heart attack during production; Loyal Griggs, who won an Academy Award for his cinematography on Stevens’ 1953 Western classic Shane, was brought in to replace him. Joanna Dunham became pregnant, which required costume redesigns and carefully chosen camera angles.[3]

Much of the production was shot during the winter of 1962-1963, when Arizona had heavy snow. Actor David Sheiner, who played James the Elder, quipped in an interview about the snowdrifts: "I thought we were shooting Nanook of the North."[19] Stevens was also under pressure to hurry the John the Baptist sequence, which was shot at the Glen Canyon area – it was scheduled to become Lake Powell with the completion of the Glen Canyon Dam, and the production held up the project.[3]

Stevens brought in two veteran filmmakers. Jean Negulesco filmed sequences in the Jerusalem streets while David Lean shot the prologue featuring Herod the Great.[5] Lean cast Claude Rains as Herod.[20]

By the time shooting was completed in August 1963, Stevens had amassed six million feet of Ultra Panavision 70 film (about 1829 km or 1136 miles, roughly the radius of the Moon). The budget ran to $20 million (equivalent to $142 million in 2010) plus additional editing and promotion charges,[21] making it the most expensive film shot in the U.S.[5][22]

The film was advertised on its first run as being shown in Cinerama. While it was shown on an ultra-curved screen, it was with one projector. True Cinerama required three projectors running simultaneously. A dozen other films were presented this way in the 1960s.

Release and reception

The Greatest Story Ever Told premiered 15 February 1965, 18 months after filming wrapped, at the Warner Cinerama Theatre in New York City. Critical reaction toward the movie was divided once it premiered. In its favor, Variety called the film "a big, powerful moving picture demonstrating vast cinematic resource." The Hollywood Reporter stated: "George Stevens has created a novel, reverent and important film with his view of this crucial event in the history of mankind."[5]

However, Bosley Crowther in The New York Times wrote: "The most distracting nonsense is the pop-up of familiar faces in so-called cameo roles, jarring the illusion." Shana Alexander in Life Magazine stated: "The pace was so stupefying that I felt not uplifted – but sandbagged!"[5] And John Simon – later notorious as the frequently scathing theater and film critic of New York Magazine – wrote: "God is unlucky in The Greatest Story Ever Told. His only begotten son turns out to be a bore."[23] Bruce Williamson, in Playboy Magazine, likewise called the movie "a big windy bore."[24]

Brendan Gill wrote in The New Yorker:

- If the subject matter weren't sacred in the original, we would be responding to the picture in the most charitable way possible by laughing at it from start to finish; this Christian mercy being denied us, we can only sit and sullenly marvel at the energy for which, for more than four hours, the note of serene vulgarity is triumphantly sustained.[24]

Stevens told a New York Times interviewer: "I have tremendous satisfaction that the job has been done – to its completion – the way I wanted it done; the way I know it should have been done. It belongs to the audiences now…and I prefer to let them judge."[5] Reviews to the film continue to be mixed, as it currently holds a 37% rating on Rotten Tomatoes based on 19 reviews.[25]

The original running time was 4 hr 20 min (260 min).[23] The time was revised three times, to 3 hr 58 min (238 min); to 3 hr 17 min (197 min) for the United Kingdom, and finally 2 hr 17 min (137 min) for general U.S. release.[3] Commercially, the film was not successful (by 1983 it had grossed less than $8 million, perhaps 17 percent of the amount required to break even),[21] and its inability to connect with audiences discouraged production of biblical epics for years.[26]

For the 2001 DVD release, a 3 hr 19 min (199 min) version was presented along with a documentary called He Walks With Beauty, which detailed the film’s tumultuous production history. Its Blu-ray release appeared in 2011.[13]

Despite the mixed critical reception and low box office receipts, The Greatest Story Ever Told was nominated for five Academy Awards:[27]

| Awards | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Award | Date of ceremony | Category | Recipient | Outcome |

| Academy Awards[28] | April 18, 1966 | Best Cinematography, Color | William C. Mellor (posthumous nomination) and Loyal Griggs | Nominated |

| Best Art Direction – Set Decoration, Color | Art Direction: Richard Day, William J. Creber, and David S. Hall (posthumous nomination) Set Decoration: Ray Moyer, Fred M. MacLean, and Norman Rockett | |||

| Best Costume Design, Color | Marjorie Best and Vittorio Nino Novarese | |||

| Best Effects, Special Visual Effects | J. McMillan Johnson | |||

| Best Music, Score – Substantially Original | Alfred Newman | |||

The film is recognized by American Film Institute in these lists:

- 2005: AFI's 100 Years of Film Scores – Nominated[29]

- 2006: AFI's 100 Years...100 Cheers – Nominated[30]

- 2008: AFI's 10 Top 10:

- Nominated Epic Film[31]

See also

- List of American films of 1965

- Cultural depictions of Jesus

- King of Kings – an earlier film about the life of Jesus, released in 1961.

- Whitewashing in film

References

- ↑ Tino Balio, United Artists: The Company That Changed the Film Industry, University of Wisconsin Press, 1987 p. 133

- ↑ "The Greatest Story Ever Told, Box Office Information". The Numbers. Retrieved January 22, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Medved, Harry & Michael. "The Hollywood Hall of Shame." Perigree Books, 1984. ISBN 0-399-50714-0

- ↑ Henry Denker, who wrote or co-wrote many of the radio episodes, was co-recipient of the purchase money - see Hollywood Hall of Shame p. 134

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Giant". google.com.

- ↑ The movie's opening credits include: Screenplay by James Lee Barrett and George Stevens, based on the Books of the Old and New Testaments, Other Ancient Writings, the Writings of Fulton Oursler and Henry Denker, and in Creative Association with Carl Sandburg (see Hollywood Hall of Shame, p. 136)

- ↑ Walker, John. "Halliwell's Who's Who in the Movies." HarperCollins, 2001. ISBN 0-06-093507-3

- ↑ Hollywood Hall of Shame, p. 138

- ↑ "The Greatest Story Ever Told". Turner Classic Movies.

- ↑ "It is impossible for those watching the film to avoid the merry game of 'Spot the Star', and the road to Calvary in particular comes to resemble the Hollywood Boulevard 'Walk of Fame'." Hollywood Hall of Shame, p. 137

- ↑ There is no Sake Moab in Utah, although Medved wrote that in Hollywood Ball of Shame

- ↑ Land, Barbara; Myrick Land (1995). A short history of Reno. Reno, Nevada: University of Nevada Press. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-87417-262-1.

- 1 2 "DVD Verdict Review - The Greatest Story Ever Told". DVD Verdict.

- ↑ http://www.retroweb.com/40acres_desilu_years.html

- ↑ "The Greatest Story Ever Told (1965) - Trivia - TCM.com". Turner Classic Movies.

- ↑ Hollywood Hall of Shame p. 139

- ↑ John Consodine stated, "I only signed up for 15 weeks on location, but I ended up staying for 54." see Hollywood Hall of Shame, p. 140

- ↑ "For the 'Raising of Lazarus' scene, for example, Stevens ordered more than 30 different camera setups and forced the actors through their paces 20 times." Hollywood Hall of Shame, p. 140

- ↑ "Several hundred volunteers . . braved the elements with shovels, wheelbarrows, bulldozers, and fifty butane flame throwers to remove the snow from the expensive replica of the Holy Land." Hollywood Hall of Shame, p. 140

- ↑ Skal, David J. "Claude Rains: An Actor’s Voice." University Press of Kentucky, 2008. ISBN 978-0-8131-2432-2

- 1 2 Hollywood Hall of Shame, p. 142

- ↑ "Such giants as Cleopatra and Lawrence of Arabia did boast bigger budgets, but they were shot on foreign soil." Hollywood Hall of Shame, p. 137

- 1 2 "Jesus Christ, cinema star". Boston.com.

- 1 2 quoted in Hollywood Hall of Shame, p. 141

- ↑ "The Greatest Story Ever Told". rottentomatoes.com. 15 February 1965.

- ↑ Steven D. Greydanus. "The Greatest Story Ever Told (1965)". Decent Films.

- ↑ "NY Times: The Greatest Story Ever Told". NY Times. Retrieved 2008-12-26.

- ↑ "The 38th Academy Awards (1966) Nominees and Winners". oscars.org. Retrieved 2016-08-04.

- ↑ "AFI's 100 Years of Film Scores Nominees" (PDF). Retrieved 2016-08-14.

- ↑ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Cheers Nominees" (PDF). Retrieved 2016-08-14.

- ↑ "AFI's 10 Top 10 Nominees" (PDF). Retrieved 2016-08-19.

External links

- The Greatest Story Ever Told at the American Film Institute Catalog

- The Greatest Story Ever Told at the Internet Movie Database

- The Greatest Story Ever Told at the TCM Movie Database

- The Greatest Story Ever Told at AllMovie

- The Greatest Story Ever Told at Rotten Tomatoes