The Holocaust in Belarus

| Part of a series on | ||||||||||

| The Holocaust | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

Atrocities |

||||||||||

|

Camps

|

||||||||||

|

Lists Deportations of French Jews

to death camps |

||||||||||

|

Remembrance |

||||||||||

The Holocaust in Belarus in general terms refers to the Nazi crimes committed during World War II on the territory of Belarus against Jews, ethnic Belarusians as well as other peoples deemed unworthy of life. The borders of Belarus however, changed dramatically following the Soviet invasion of Poland in 1939, which has been the source of confusion especially in the Soviet era as far as the scope of the Holocaust in Belarus is concerned.[1][2]

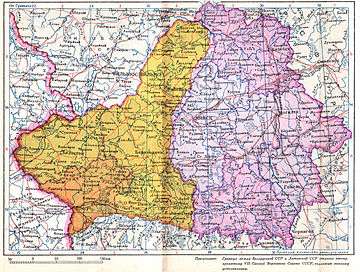

Before World War II began, with the September 1, 1939 attack on Poland by Nazi Germany, sovereign Belarus of today did not exist yet. The Nazi-Soviet Pact signed in secrecy led to the parallel Soviet invasion of Poland from the east on September 17, 1939. The eastern half of prewar Poland was annexed by the USSR to the two republics of Soviet Belarus and Soviet Ukraine in the atmosphere of terror.[3][4] The cities were renamed in Russian, the new Oblasts created,[5] and millions of Polish citizens turned by force into the new Soviet subjects.[6] Meanwhile, the Holocaust perpetrated by the Third Reich in the territory of Soviet Belarus began twenty-one months later in 1941, during the German attack on the Soviet positions, in Operation Barbarossa.[7][8]

The communist Soviet-era sources estimated that Belarus lost a quarter of its prewar population in World War II, including most of its intellectual elite. It is a myth believed to have been concocted by the local 1st Secretary Pyotr Masherov in a speech of 8 May 1965 according to western historians who point out to evidence of manipulation by the Extraordinary State Commission inflating the figure considerably by including victims who were not citizens of the republic.[9][10][11] The official memorial narrative of Belarus allows only a "pro-Soviet version of the resistance to the German invaders."[12][13] The Constitution of the Republic under Article 28 denies access to information about Belarusians who served with the Nazis.[14]

The entire territory of modern-day Belarus was occupied by Nazi Germany by the end of August 1941.[15] American historian Lucy Dawidowicz, author of The War Against the Jews estimated that 66 percent of the Jewish people residing in Belarusian SSR died in the Holocaust, out of 375,000 Jews in White Russia prior to World War II according to Soviet data. By comparison, in the Baltics about 90 percent of Jews were killed in the same timeframe.[16]

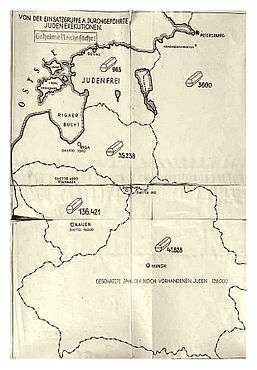

German invasion

Resulting from the Soviet invasion of Poland in 1939, the territory of Belarusian SSR was greatly enlarged by Joseph Stalin through the annexation of Kresy.[17] Within two years, the Jewish population of Minsk, the capital of the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic, had swelled to 90,000 due to influx of Polish Jews escaping German occupation.[18] Upon the German invasion of the Soviet Union two years later, Minsk was bombed and taken over by the Wehrmacht on 28 June 1941.[18] Operation Barbarossa was a war against the "Jewish Bolshevism" in Hitler's view.[19] On 3 July 1941 during the first "selection" in Minsk 2,000 Jewish members of the intelligentsia were marched off to a forest and massacred.[18] The atrocities committed beyond the German–Soviet frontier were summarized by Einsatzgruppen for both sides of the prewar border between BSSR and Poland.[17]

The Nazis made Minsk the administrative centre of Reichskomissariat Ostland. As of 15 July 1941 all Jews were ordered to wear a yellow badge on their outer garments under penalty of death, and on 20 July 1941 the creation of the Minsk Ghetto was pronounced.[18] Within two years, it became the largest ghetto in German-occupied Soviet Union,[20] with over 100,000 Jews.[18]

A fair percentage of ethnic Belarusians supported Nazi Germany,[21] especially in the early years. Some nationalists out of Minsk including sworn Germanophile Ivan Yermachenka hoped for the formation of a Belarusian national state under protectorate of the Reich. By the end of 1942 the Yermachenka's group known as BNS had 30,000 members in a dozen different Soviet cities.[22] The Belarusian Auxiliary Police was established by the Nazi authorities in the summer of 1941.[23] High-ranking positions in the police were also kept by BNS.[22] "Known to the Germans as the Schutzmannschaft – wrote Martin Dean – the local police were recruited from volunteers at the start of the occupation. These men played an indispensable role in the killing process."[24] Eventually, the number of local auxiliary police in German-occupied Soviet Union reached 300,000 men.[25]

The southern part of the modern-day Belarus was annexed to the newly formed Reichskommissariat Ukraine on 17 July 1941 including the easternmost Gomel Region of the Russian SFSR, and several others.[26] They became part of the Shitomir Generalbezirk centred around Zhytomyr. The Germans determined the identities of the Jews either through registration, or by issuing decrees. The Jews were separated from the general population and confined to makeshift ghettos. Because the Soviet leadership fled from Minsk without ordering evacuation, most Jewish inhabitants have been captured.[26][27] There were 100,000 prisoners held in the Minsk Ghetto, in Bobruisk 25,000, in Vitebsk 20,000, in Mogilev 12,000, in Gomel over 10,000, in Slutsk 10,000, in Borisov 8,000, and in Polotsk 8,000.[28] In the Gomel Region alone, twenty ghettos were established in which no less than 21,000 people were imprisoned.[26]

In November 1941 the Nazis rounded up 12,000 Jews in the Minsk Ghetto to make room for the 25,000 foreign Jews slated for expulsion from Germany, Austria and the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia.[18] On the morning of 7 November 1941 the first group of prisoners were formed into columns and ordered to march singing revolutionary songs. People were forced to smile for the cameras. Once beyond Minsk, 6,624 Jews were taken by lorries to the nearby village of Tuchinka (Tuchinki) and shot by members of Einsatzgruppe A.[29] The next group of over 5,000 Jews followed them to Tuchinka on 20 November 1941.[30]

Holocaust by bullet

Resulting from the Soviet annexation of present-day Western Belarus in 1939, the Jewish population of BSSR nearly trippled.[31] In June 1941, at the beginning of Operation Barbarossa, there were 670,000 Jews on the Polish side and 405,000 Jews on the Soviet side of Belarus.[31] On 8 July 1941 the SS-Obergruppenführer Reinhard Heydrich gave the order for all male Jews in the occupied territory – between the ages of 15 and 45 – to be shot on sight as Soviet partisans. By August, the victims targeted in the shootings included women, children, and the elderly.[32] The German police battalions as well as the Einsatzgruppen carried out the first wave of killings. The role of the Belarusian Auxiliary Police, established on 7 July 1941, was crucial in the totality of procedures, as only they – wrote Martin Dean – knew the identity of the Jews.[33] The pacification actions were conducted using Schutzmannschaft during roundups (as in Homel, Mozyrz, Kalinkowicze, Korma). The local police took on a secondary role. The ghettoised Jews were controlled by them and brutalized before mass executions (as in Dobrusz, Czeczersk, Żytkowicze).[26][34] After a while the already-trained auxiliary police not only led the Jews out of the ghettos to places of massacres but also took active part in the shootings. Such tactic was successful (without much exertion of force) in places where the killings of Jews were carried out in early September, and throughout October and November 1941. In winter 1942, a different tactic was introduced - the pacification raids, conducted in Żłobin, Petryków, Streszyn, Czeczersk.[26] The role of the Belarusian police in the killings became particularly noticeable during the second wave of the ghetto liquidations,[35] starting in February–March 1942.[23][26]

In the Holocaust by bullet, no less than 800,000 Jews perished in the territory of modern-day Belarus.[31] Most of them were shot by Einsatzgruppen, Sicherheitsdienst and Orpo battalions aided by Schutzmannschaften.[31] Notably, when the bulk of the Jewish communities were annihilated in first major killing spree, the number of Belarusian collaborators was still considerably small, therefore the Eastern European destruction battalions consisted in most part of Lithuanian, Ukrainian, and Latvian volunteers.[36] Historian Martin Gilbert wrote that the General-Commissar for Generalbezirk Weißruthenien, Wilhelm Kube, personally participated in the March 2, 1942 killings in the Minsk Ghetto. During the search of the ghetto area by the Nazi police, a group of children were seized and thrown into deep pit of sand covered with snow. "At that moment, several SS officers, among them Wilhelm Kube, arrived, whereupon Kube, immaculate in his uniform, threw handfuls of sweets to the shrieking children. All the children perished in the sand."[37]

On 22 September 1943, Wilhelm Kube was assassinated in Minsk by his Belarusian mistress.[38] His death was caused by a bomb hidden in a hot water bottle, which was placed in his bed by Jelena Mazanik, coerced by the Soviet agents who knew where her son was.[38] The SS executed more than 1,000 male citizens of Minsk in retaliation, though SS leader Heinrich Himmler reportedly said the assassination was a "blessing" since Kube did not support some of the harsh measures mandated by the SS.[39] Mazanik escaped and joined the partisans. SS and Police Leader Curt von Gottberg was successively promoted as the head of SS and police for Belarus between October 1942 and June 1944 due to Himmler's sponsorship. He was delegated with the duties of the Generalkommissar for Belarus on October 27, 1943 after Kube was killed by a bomb in Minsk on October 23. Von Gottberg developed a new "strategy" in the fight against partisans on the occupied territory of the Soviet Union, mounting aggressive operations against suspected "partisan bases" (generally ordinary villages; Gottberg's strategy seems to have largely involved terrorising the civilian population). Whole regions were classified as "bandit territory" (German: Bandengebiet): residents were expelled or murdered and dwellings destroyed. Gottberg said in an order "In the evacuated areas all people are in future fair game". Another order of Gottberg's of December 7, 1942, stated: "Each bandit, Jew, gypsy, is to be regarded as an enemy". After his first operation, Nürnberg, Gottberg reported on December 5, 1942: "Enemy dead: 799 bandits, over 300 suspected gangsters and over 1800 Jews [...] Our losses: 2 dead and 10 wounded. One must have luck".

Mass murders in Nawahrudak

Nazi Germany launched the attack on the Soviet positions in Eastern Poland on 22 June 1941. The city of Navahrudak (Nowogródek in Polish), capital of the Nowogródek Voivodship in interwar Poland (invaded by the Soviet Union in 1939), was occupied on July 4, 1941. According to the Polish census of 1931 the Nowogródek Voivodeship was home to about 616,000 ethnic Belorussians, or ~39% of the total population of the province. The number of ethnic Belorussians exceeded the number of ethnic Poles by eight percentage points.[40] The Red Army forces were surrounded, in what is known as the Navahrudak Cauldron. Prior to the war, the area population was 20,000, of which about half were Polish Jews. During a series of actions, the Germans killed all but 550 of the approximately 10,000 Jews. Those not killed were sent into slave labor. During the German occupation the city became part of the Reichskommissariat Ostland. Partisan resistance immediately began, with most famous Bielski partisans formed of Jewish volunteers operated in the region. On July 31, 1943, without warning or provocation, 11 of the Sisters of the Holy Family of Nazareth were imprisoned, loaded into a van and driven beyond the town limits.[41] The 11 nuns were killed on August 1, 1943, in the woods 5 km (3.1 mi) beyond Navahrudak, and buried in a mass grave. After the execution, Sister M. Malgorzata Banas, the community's sole surviving member, located the place of the martyrdom, and remained the guardian of their common grave until her own death in 1966. The Church of the Transfiguration, known as Biała Fara, or "White Church", now contains the relics of the eleven martyrs.

The Red Army liberated the city almost exactly three years after its occupation on July 8, 1944. During the war more than 45,000 people were killed in the city and in the surrounding area, and over 60% of buildings was destroyed.

Anti-partisan operations

The cruelty during anti-partisan operations, especially in Belarus, has been pointed out in the past, indicating a high degree of identification with their deeds rather than an unwilling execution. The meanness of their actions is evidenced by the means of mass killings employed by the Germans in their fight against partisans. Most of the victims were women and children,[42] as the male population of the villages had been evacuated or drafted into the Red Army, or joined the partisans. They were also used as a labor force. Similar aspects also apply to the murder of Jews, prisoners of war, political opponents, and the ill.

The Battalion Dirlewanger on July 21, 1943, during Operation Hermann, chased the inhabitants of the village of Dory together with the priest into a church and burned them alive there. Only men able to work were let out of the church, women only if they left their children behind. At another place hundreds of selected children, two to ten years old, were locked in freight cars and left to their fate until half of them had died. While von Schenkendorff in 1942 called for measures against the soldiers, the generally organized sequence of the destruction of villages shows how little was left to chance.

Photo albums were prepared for higher SS commanders after anti-partisan actions. Thus, Erich von dem Bach-Zelewski readily admitted to have possessed thousands of color photographs of the fight against partisans, photos which were confiscated after the war. After Operation Hermann in the summer of 1943, Curt von Gottberg requested appropriate pictures for an album on partisan fighting, to be handed to Himmler. Some months later, he was sent an album featuring photos from Operation Heinrich, which Bach-Zelewski had dedicated to Himmler by naming it after him. The rank and file behaved in a similar manner. Many German participants had a camera in their backpack during the operations. The respective pictures mostly show rather uncompromising scenes, but often also the burning of villages.[43]

Another aspect was the fact that inhabitants of the countryside were used for de-mining the roads and other pathways to partisan camps, and were massively forced to walk the ways leading there. Several thousand Belarussians were killed due to this. Such cases already occurred in Wehrmacht-controlled areas 1942, at the remote village of Uchwała, Krupki, where a total of 360 people perished. In the area of the 286th Security Division, the civilian population had to walk, plough and harrow the roads on the orders of Major General Richert from the autumn of 1942. At Artiszewo near Orsza, 28 people, 18 of which were children, perished during this operation. The LIX Army Corps had issued a corresponding order already on March 2, 1942.

Later, they also used herds of sheep. But in most cases people were used, on an ever larger scale. During Operation Cottbus, between 2,000 and 3,000 Belarusians whom the Germans drove before them into the swamps were torn apart by mines, according to Bach-Zelewski. After preparation by artillery and flak, entering the swamp area was only possible by chasing inhabitants of the region across the heavily mined paths through the swamp. Oskar Dirlewanger's corresponding order of May 25, 1943 had read:

Roadblocks and artificial obstacles are almost always mined. So far we have suffered 1 dead and 4 wounded during removal. Thus the order is: Never remove obstacles yourselves, but always let natives do it. The blood thus saved justifies the loss of time.

For Operation Hermann conducted in July–August 1943 partly by Einsatzgruppe Dirlewanger the same directive applied right from the beginning. The commanders carried out the instructions. The same occurred during Operation Frühlingsfest (April 16 till May 10, 1944), which was carried out in equal parts by Wehrmacht and SS units. A corresponding suggestion is said to have come from the already mentioned Richert. But in the meantime, this method had become routine also outside the scope of major actions. It was also applied by Wehrmacht frontline troops in their direct rear area. All Belarusians had become hostages of the Germans. The 78th Infantry division ordered the whole civilian population in its area to de-mine the roads area every morning for six hours:

I thus order that all roads that must be driven on by German troops are to be walked first by all inhabitants of the location (including women and children) with cows, horses and vehicles up to the next command post, or that marching columns must be preceded at a distance of at least 150 meters by such inhabitants. The civilians must close up tightly and walk the whole width of the road.

Rear area command 532 proceeded in a similar manner, and an officer in the high command of Army Group Center wanted to recommend this procedure as exemplary to other units. As of February 18, 1944, General Commissar v. Gottberg issued a Directive for the Securing of Traffic Roads in White Ruthenia against Bandits and Mines. Therein the whole population of villages in White Ruthenia was obliged to de-mine streets and roads every day at the regional police commanders instructions. Whoever refused the de-mining and road supervision service was to be punished by death.[43]

Massacres

The pacifications, and the ghetto liquidation actions in the territories occupied by the Germans since June 1941, were conducted in a number of notable locations in present-day Belarus. The victims, including Polish Jews from the territories annexed into the Soviet Belarus from the Polish Kresy, were also transported by rail to the Bronna Góra extermination site whenever deemed necessary by the executioners. The towns (in alphabetical order) included Antopol,[44] Berazino, Novogrudok (see Blessed Martyrs of Nowogródek), Bobruisk, Chavusy, Davyd-Haradok, Dzyatlava (see Dzyatlava massacre), Grodno (see Grodno Ghetto), Iwye, Khatyn (see Khatyn massacre), Lakhva (see Łachwa Ghetto), Lida, Luniniec, Lyubavichi, Trostenets (see Maly Trostenets extermination camp), Minsk (see Minsk Ghetto), Motal, Obech, Pinsk (see Pińsk Ghetto), Polotsk, Ponary (see Ponary massacre), Shkloŭ, Slonim (see Słonim Ghetto), Slutsk (see Slutsk Affair), Vitebsk (see Vitebsk Ghetto), and Zhetel (see Zdzięcioł Ghetto).

According to State Memorial Complex "Khatyn" created by the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Belarus, the Nazi regime deported to Germany for slave labour some 380,000 Ostarbeiters and killed hundreds of thousands of civilians. At least 5,295 Belarusian settlements were destroyed and their inhabitants murdered (out of 9,200 settlements that were burned or otherwise destroyed in Belarus during World War II). According to SMC "Khatyn", 243 Belarusian villages were burned twice, 83 villages three times, and 22 villages were burned four or more times in the Vitebsk region. In the Mińsk region 92 villages were burned twice, 40 villages three times, nine villages four times, and six villages five or more times.[45] More than 600 villages like Khatyn (see: the Khatyn massacre) were annihilated with their entire population. More than 209 cities and towns (out of 270 total) were destroyed.[45][46]

Postwar research

In the 1970s and 1980s historian and Soviet refusenik Daniel Romanovsky who later emigrated to Israel, interviewed over 100 witnesses, including Jews, Russians, and Belarusians from the vicinity, recording their accounts of the Holocaust by bullet.[47][48][49][50] Research on the topic was difficult in the Soviet Union because of government restrictions. Nevertheless, based on his interviews Romanovsky concluded that the open-type ghettos in Belarusian towns were the result of prior concentration of the entire Jewish communities in prescribed areas. No walls were required.[47] The collaboration with the Germans by most non-Jewish people was in part a result of attitudes developed under the Soviet rule; namely, the practice of conforming to a totalitarian state. Sometimes called Homo Sovieticus.[51][52][53]

See also

- Bielski partisans

- Defiance (2008 film)

- The Holocaust in Lithuania

- The Holocaust in Poland

- Judenfrei

- Operation Ostra Brama

- Reichskommissariat Moskau

- Reichskommissariat Ostland

- Ukrainian-German collaboration during World War II

- Vitsyebsk gate

| Part of a series on |

| Genocide |

|---|

| Issues |

| Documented instances |

|

| Related topics |

References

- ↑ Doron Halutz (7 March 2013). "U.S. historian revives controversy in Holocaust studies". Yale professor Timothy Snyder examines the killing policy that entwined the Nazi and Soviet regimes. Haaretz.com. Archived from the original (Internet Archive print option) on March 17, 2015. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ↑ Timothy Snyder (16 July 2009). "Holocaust: The Ignored Reality". The New York Review of Books. Archived from the original (Internet Archive) on January 9, 2014. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ↑ Bernd Wegner (1997). From peace to war: Germany, Soviet Russia, and the world, 1939–1941. Berghahn Books. pp. 74–92. ISBN 1-57181-882-0.

- ↑ Eugeniusz Mironowicz. "Stosunki polsko-białoruskie pod okupacją sowiecką" [Polish-Belarusian relations under the Soviet occupation]. Przesiedlenia ludności z Białorusi do Polski i z Polski do Białorusi (in Polish). Bialorus.pl. Archived from the original on May 29, 2010. Retrieved 17 March 2015 – via Internet Archive.

- ↑ Northeastern territories of Poland were attached to Belastok Voblast, Hrodna Voblast, Navahrudak Voblast (soon renamed to Baranavichy Voblast), Pinsk Voblast and Vileyka (later Maladzyechna) Voblast of Byelorussian SSR

- ↑ Gross, Jan Tomasz (2002). Revolution from Abroad: The Soviet Conquest of Poland's Western Ukraine and Western Belorussia. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. p. 17. ISBN 0-691-09603-1.

Indeed, the two-week campaign that brought the USSR 200,000 square kilometers of territory, 13.5 million new subjects, and 250,000 prisoners of war, cost it, according to Molotov, fewer than 3,000 casualties..

- ↑ Gross, Jan Tomasz (2003) [2002]. Revolution from Abroad. Princeton. p. 396. ISBN 0-691-09603-1 – via Google Books.

- ↑ George Sanford. Katyn and the Soviet Massacre of 1940: Truth, Justice and Memory (Google Books). pp. 20–24.

- ↑ Prof. David Marples, University of Alberta (2014). 'Our Glorious Past': Lukashenka's Belarus and the Great Patriotic War. Columbia University Press. p. 2. ISBN 3838266749.

- ↑ Andrej Kotljarchuk (2013). "World War II Memory Politics: Jewish, Polish, and Roma Minorities of Belarus" (PDF). 7 (1). Journal of Belarusian Studies: 10, 7–37.

On the basis of the claimed figures, a myth about ‘every fourth inhabitant of the republic’ who perished was created, which did not fit even the broadest mathematical calculations. The myth's author was Piotr Mašeraŭ, the leader of Soviet Belarus in the years 1965 to 1980.

- ↑ Oleg Litskevich (2009). "Liudskie poteri Belarusi v voine". "Ničoha nie zabudziem (1943)" : Extraordinary State Commission for Ascertaining and Investigating Crimes Perpetrated by the German Fascist Invaders and their Collaborators. Bielaruskaja Dumka (5 May): 92–97.

The grossly inflated figure included 800,000 prisoners of war and 1.4 million civilians most of whom were not citizens of the republic.

- ↑ Alexandra Goujon (28 August 2008). "Memorial Narratives of WWII Partisans and Genocide in Belarus". France: University of Bourgogne: 4 – via DOC file, direct download.

- ↑ John-Paul Himka and Joanna Beata Michlic. "Bringing the Dark Past to Light. The Reception of the Holocaust in Postcommunist Europe" (PDF). University of Nebraska Press: 16. ISBN 0803246471.

- ↑ Meredith M. Meehan (2010). "Auxiliary Police Units in the Occupied Soviet Union, 1941-43: A Case Study of the Holocaust in Gomel, Belarus" (PDF). United States Naval Academy: 44 – via PDF file, direct download 2.13 MB.

- ↑ SMC "Khatyn" (2005). "Genocide policy". Khatyn.by.

Memorial complex Khatyn built in 1969 by Central Committee of the Communist Party of Belarus is situated in Logoisk region of Minsk.

- ↑ Dawidowicz, Lucy (1986). The War Against the Jews. Bantam. pp. 403, 485 – via Google Books.

- 1 2 3 Hilberg, Raul (2003). The Destruction of the European Jews. Yale University Press. pp. 1313–1316. ISBN 0300095929.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 ARC (26 June 2006). "Minsk Ghetto". Hilberg 2003, Gilbert 1986, Ehrenburg 1981, Arad 1987, Gutman 1990, Klee 1991, et al. Aktion Reinhard Camps – via Internet Archive.

- ↑ Leonid Rein (2013). The Kings And The Pawns: Collaboration in Byelorussia during World War II. Berghahn Books. p. 85. ISBN 1782380485.

- ↑ Donald L. Niewyk, Francis R. Nicosia (2000). The Columbia Guide to the Holocaust. The Minsk Ghetto. Columbia University Press. pp. 205, 156–165, 205–208. ISBN 0231505906.

- ↑ Marek Wierzbicki. "Stosunki polsko-białoruskie pod okupacją sowiecką (1939–1941)" [Polish-Belarusian relations under the Soviet occupation]. НА СТАРОНКАХ КАМУНІКАТУ. Białoruskie Zeszyty Historyczne (20 (2003)): 186–188 – via Internet Archive.

- 1 2 Leonid Rein (2013). The Kings And The Pawns. pp. 144–145. ISBN 1782380485.

- 1 2 Alexey Litvin (Алексей Лiтвiн), Participation of the local police in the extermination of Jews (Участие местной полиции в уничтожении евреев, в акциях против партизан и местного населения.); (in) Местная вспомогательная полиция на территории Беларуси, июль 1941 — июль 1944 гг. (The auxiliary police in Belarus, July 1941 - July 1944).

- ↑ Martin Dean (2003). Collaboration in the Holocaust: Crimes of the Local Police in Belorussia and Ukraine, 1941-44. Palgrave Macmillan. p. viii. ISBN 1403963711.

- ↑ Andrea Simon (2002). Bashert: A Granddaughter's Holocaust Quest. Atonement. Univ. Press of Mississippi. p. 225. ISBN 1578064813.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Dr. Leonid Smilovitsky (September 2005). Fran Bock, ed. "Ghettos in the Gomel Region: Commonalities and Unique Features, 1941-42". Letter from Ilya Goberman in Kiriat Yam (Israel), September 17, 2000. Belarus SIG, Online Newsletter No. 11/2005.

Note 16: Archive of the author; Note 17: M. Dean, Collaboration in the Holocaust.

- ↑ Daniel Romanovsky. Zvi Gitelman, ed. "Soviet Jews under the Nazi Occupation (Data on North-Eastern Byelorussia and Northern Russia)" (PDF). History, Politics and Memory: The Holocaust and Its Contemporary Consequences in the Former USSR. The National Council for Soviet and East European Research. p. 25 (30 / 39 in PDF).

- ↑ "Gosudarstvenny arkhiv Rossiiskoy Federatsii (GARF): F. 8114, Op. 1, D. 965, L. 99" Государственный архив Российской Федерации (ГАРФ): Ф. 8114. Оп. 1. Д. 965. Л. 99 [State Archive of the Russian Federation] (PDF). 110, 119 / 448 in PDF – via direct download, 3.55 MB from Iz istorii evreiskoi kultury.

Геннадий Винница (Нагария), »Нацистская политика изоляции евреев и создание системы гетто на территории Восточной Белоруссии«

- ↑ Jewish Virtual Library. "Operational Situation Report no. 140". Activities of Einsatzgruppe A.

The Chief of the Security Police and the Security Service, Berlin, December 1, 1941; OSR #140.

- ↑ Snyder, Timothy (2011) [2010]. Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin. Vintage, Basic Books. pp. 226–227. ISBN 0465002390.

- 1 2 3 4 Per Anders Rudling (2013). John-Paul Himka, Joanna Beata Michlic, eds. Invisible Genocide. The Holocaust in Belarus. Bringing the Dark Past to Light. University of Nebraska Press. pp. 60–62. ISBN 0803246471.

- ↑ Longerich, Peter (2010). Holocaust: The Nazi Persecution and Murder of the Jews. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. p. 198. ISBN 978-0-19-280436-5.

- ↑ Martin Dean (2003). "The Ghetto 'Liquidations'". Collaboration in the Holocaust: Crimes of the Local Police in Belorussia and Ukraine, 1941–44. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 18, 22, 78, 93. ISBN 1403963711 – via Goggle Books.

- ↑ Dean, Martin (2000). Collaboration in the Holocaust. Crimes of the Local Police in Belorussia and Ukraine, 1941-1944. New York: St. Martin's Press (in association with USHMM). pp. 77–8. ISBN 1403963711.

- ↑ Andrea Simon (2002). Bashert: A Granddaughter's Holocaust Quest. Univ. Press of Mississippi. p. 228. ISBN 1578064813.

- ↑ Rudling (2013). Invisible Genocide. p. 61. ISBN 0803246471.

- ↑ Gilbert, Martin (1986). The Holocaust: the Jewish tragedy. Fontana/Collins. p. 296. OCLC 15223149.

- 1 2 Andrew Wilson (2011). "The Traumatic Twentieth Century" (PDF file, direct download 16.4 MB). Belarus: the last European dictatorship. Yale University Press. pp. 109–110. Retrieved 10 July 2014.

- ↑ Reidlinger 1960, p. 157, as quoted in Turonek 1989, p. 118.

- ↑ Tadeusz Piotrowski (1998). Poland's Holocaust. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-0371-4.

The number of Belorussians in the Republic, according to Tomaszewski, were distributed as follows: Polesie, 654,000; Nowogrodek, 616,000; Wilno, 409,000; and Bialystok, 269,100

- ↑ Lapomarda, Vincent A. (S.J.) (2000-02-22). "The Eleven Nuns of Navahrudak". College of the Holy Cross. Retrieved 2008-02-27.

- ↑ See also The history of children in the Holocaust

- 1 2 Gerlach, Christian (2000). Kalkulierte Morde. Die deutsche Wirtschafts- und Vernichtungspolitik in Weißrußland 1941 bis 1944 (in German). Hamburger Edition. Studienausgabe. p. 955 and following. ISBN 978-3930908639.

- ↑ Stephen P. Morse (1942-10-15). "Antipolia History". Stevemorse.org – via Internet Archive.

- 1 2 "Genocide policy". Khatyn.by. SMC "Khatyn". 2005. Retrieved 1 August 2006.

- ↑ "Khatyn WWII Memorial in Belarus". Belarusguide.com. 1943-03-22. Retrieved 2012-03-28.

- 1 2 Martin Dean (2005). Jonathan Petropoulos, John Roth, eds. Gray Zones: Ambiguity and Compromise in the Holocaust and its Aftermath. Life and Death in the Ghettos. Berghahn Books. p. 209.

- ↑ Rudling (2013). The Invisible Genocide. [in:] Bringing the Dark Past to Light. pp. 74, 78.

Between 1941 and 1945, Belarusians in the various German collaborationist formations numbered between 50,000 and 70,000 men.

- ↑

- Romanovsky, Daniel (2009), "The Soviet Person as a Bystander of the Holocaust: The case of eastern Belorussia", in Bankier, David; Gutman, Israel, Nazi Europe and the Final Solution, Berghahn Books, p. 276

- "The Holocaust in the Eyes of Homo Sovieticus: A Survey Based on Northeastern Belorussia and Northwestern Russia". Holocaust Genocide Studies. 13 (3): 355–382. 1999. doi:10.1093/hgs/13.3.355.

- Romanovsky, Daniel (1997), "Soviet Jews Under Nazi Occupation in Northeastern Belarus and Western Russia", in Gitelman, Zvi, Bitter Legacy: Confronting the Holocaust in the USSR, Indiana University Press, p. 241

- ↑ Interview

- ↑ The Kings And The Pawns: Collaboration in Byelorussia during World War II, Leonid Rein, Berghahn Books, Oct 15, 2013, pages 264-265, 285

- ↑ Leonid Rein (2013). The Kings And The Pawns. pp. 264–265, 285.

- ↑ Barbara Epstein (2008). The Minsk Ghetto 1941-1943: Jewish Resistance and Soviet Internationalism. University of California Press. p. 295.

Notes.