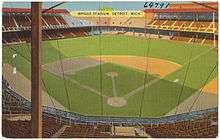

Tiger Stadium (Detroit)

| The Corner | |

|

Tiger Stadium in 1998 | |

| Former names |

Navin Field (1912–37) Briggs Stadium (1938–60) |

|---|---|

| Location |

2121 Trumbull Avenue Detroit, Michigan 48216 |

| Coordinates | 42°19′55″N 83°4′8″W / 42.33194°N 83.06889°WCoordinates: 42°19′55″N 83°4′8″W / 42.33194°N 83.06889°W |

| Owner |

Detroit Tigers (1912–77) City of Detroit (1977–2009) |

| Operator | Detroit Tigers |

| Capacity |

23,000 (1912) 30,000 (1923) 52,416 (1937) |

| Field size |

Left field – 340 ft (104 m) Left-center field – 365 ft (111 m) Center field – 440 ft (134 m) Right-center field – 370 ft (113 m) Right field – 325 ft (99 m) Backstop – 66 ft (20 m) |

| Surface | Grass |

| Construction | |

| Broke ground | October 1911 |

| Opened | April 20, 1912 |

| Closed | September 27, 1999 |

| Demolished |

June 30, 2008 (began) September 21, 2009 (completed) |

| Construction cost |

US$300,000 ($7.37 million in 2016 dollars[1]) |

| Architect | Osborn Engineering Company |

| General contractor | Hunkin & Conkey[2] |

| Tenants | |

|

Detroit Tigers (MLB) (1912–1999) | |

|

Tiger Stadium | |

| NRHP Reference # | 88003236[3] |

| Added to NRHP | February 6, 1989 |

Tiger Stadium, previously known as Navin Field and Briggs Stadium, was a baseball park located in the Corktown neighborhood of Detroit, Michigan. It hosted the Detroit Tigers Major League Baseball team from 1912–99, as well as the National Football League's Detroit Lions from 1938–74. It was declared a State of Michigan Historic Site in 1975 and has been listed on the National Register of Historic Places since 1989. The stadium was nicknamed "The Corner" for its location on Michigan Avenue and Trumbull Avenue.

The last Detroit Tigers game at the stadium was held in September 1999. In the decade after the Tigers baseball team vacated the stadium, several rejected redevelopment and preservation efforts finally gave way to demolition. The stadium's demolition was completed on September 21, 2009, though the stadium's actual playing field remains at the corner where the stadium once stood. Since the spring of 2010, a volunteer group known as the Navin Field Grounds Crew (composed of Tiger Stadium fans, preservationists, and Corktown residents) has restored and maintained the field.

A plan to redevelop the old Tiger Stadium site would retain the historic playing field for youth sports and ring the 10-acre property with new development has received final approval, and funding.[4] Developer Eric Larson of Larson Realty will develop a mixed residential and retail project along the Michigan Ave and Trumbull sides of the property, beginning in late 2016.[4] The Detroit Police Athletic League will begin construction, in early April 2016, on a new headquarters building along Michigan Ave and Cochrane. The L-shaped building would enclose two sides of the field.[4] Together these two projects will completely ring the old site.[4]

History

Origins

In 1895, Detroit Tigers owner George Vanderbeck had a new ballpark built at the corner of Michigan and Trumbull avenues. That stadium was called Bennett Park and featured a wooden grandstand with a wooden peaked roof in the outfield. At the time, some places in the outfield were only marked off with rope.

In 1911, new Tigers owner Frank Navin ordered a new steel-and-concrete baseball park on the same site that would seat 23,000 to accommodate the growing numbers of fans. Navin Field opened on April 20, 1912, the same day as the Boston Red Sox's Fenway Park. While constructed on the same site as Bennett Park, the diamond at Navin Field was rotated 90°, with home plate located in what had been left field at Bennett Park.[5] Cleveland Naps player "Shoeless" Joe Jackson, later banned from baseball for life following the Black Sox Scandal, scored the first run at Navin Field on the opening day. The intimate configurations of both stadiums, both conducive to high-scoring games featuring home runs, prompted baseball writers to refer to them as "bandboxes" or "cigar boxes" (a reference to the similarly intimate Baker Bowl).

Over the years, expansion continued to accommodate more people. In 1935, following Navin's death, new owner Walter Briggs oversaw the expansion of Navin Field to a capacity of 36,000 by extending the upper deck to the foul poles and across right field. By 1938, the city had agreed to move Cherry Street, allowing left field to be double-decked and the now-renamed Briggs Stadium had a capacity of 53,000. In 1961, new owner John Fetzer took control of the stadium and gave it its final name: Tiger Stadium. Under this name, the stadium witnessed World Series titles in 1968 and 1984.

A fire gutted the press box on the evening of February 1, 1977.[6] In 1977, the Tigers sold the stadium to the city of Detroit, which then leased it back to the Tigers. As part of this transfer, the green wooden seats were replaced with blue and orange plastic ones and the stadium's interior, which was green, was painted blue to match.

In 1992, new owner Mike Ilitch began many cosmetic improvements to the ballpark, primarily with the addition of the Tiger Den and Tiger Plaza. The Tiger Den was an area in the lower deck between first and third base that had padded seats and section waiters. The Tiger Plaza was constructed in the old players parking lot and consisted of many concessionaires and a gift shop.

After the 1994 strike, plans were made to construct a new park, but many campaigned to save the old stadium. Plans to modify and maintain Tiger Stadium as the home of the Tigers, known as the Cochrane Plan, were supported by many in the community, but were never seriously considered by the Tigers. Ground was broken for the new Comerica Park during the 1997 season.

Features

Tiger Stadium had a 125-foot (38 m) tall flagpole in fair play, to the left of dead center field near the 440 foot (134 m) mark. The same flag pole was originally to be brought to Comerica Park, but this never took place. A new flagpole in the spirit of Tiger Stadium's pole was positioned in fair play at Comerica Park until the left field fence was moved in closer prior to the 2003 season. The original Tiger Stadium flagpole, designed by Rudolph V. Herman at the request of W. O. "Spike" Briggs, is still in its original position on the now vacant site.

When the stadium closed, it was tied with Fenway Park as the oldest ballpark in Major League Baseball, the two parks having opened on exactly the same date in 1912. Taking predecessor Bennett Field into account, Tiger Stadium was the oldest Major League Baseball site in use in 1999.

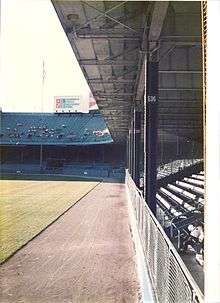

The right field upper deck overhung the field by 10 feet (3 m), prompting the installation of spotlights above the warning track. When the park was expanded in 1936 and the second deck was added over the right field pavilion and bleachers, there was a limited amount of space between the right field fence and the street behind it. To fit as many seats as possible in the expansion, the second deck was extended over the fence by 10 feet. The overhang would occasionally "catch" some extremely high arced fly balls and prevent the right fielder standing underneath it with his back to the fence from catching the ball, resulting in a home run for the batter, in what otherwise would have been a long out. Other batted balls would occasionally hit the facing of the overhang and bounce far back into right field (still resulting in a home run).

Like other older baseball stadiums such as Fenway Park and Wrigley Field, Tiger Stadium offered "obstructed view" seats, some of which were directly behind a steel support column; while others in the lower deck had sight lines obstructed by the low-hanging upper deck. By making it possible for the upper deck to stand directly above the lower deck, the support columns allowed the average fan to sit closer to the field than at any other major league baseball park.

For a time after it was constructed, the right field upper deck had a "315" marker at the foul pole (later painted over), with a "325" marker below it on the lower deck fence (which was retained).[7][8] The Texas Rangers claim that the design of the right field section was copied and used in the construction of Globe Life Park in Arlington, Texas, but in fact the upper deck does not actually extend over the right field fence, but is set back by several feet[9]

Supposedly due to then-owner Walter Briggs's dislike of night baseball, lights were not installed at the stadium until 1948. The first night game at the stadium was held on June 15, 1948. Among major league parks whose construction predated the advent of night games, only Chicago's Wrigley Field went longer without lights (1988).

Tiger Stadium featured an upper and lower deck bleacher section that was separated from the rest of the stadium. Chainlink and at one time, a barbed wire fence, separated the bleachers from the reserved sections and was the only section of seating not covered by at least part of the roof. The bleachers had their own entrance, concession stands and restrooms.

Professional football

Tiger Stadium was home to the Detroit Lions from 1938 to 1974 when they dropped their final Tiger Stadium game to the Denver Broncos on Thanksgiving Day. The stadium hosted two NFL championship games in 1953 and 1957. The football field ran mostly in the outfield from the right field line to left center field parallel with the third base line. Since the playing surface was just barely large enough for football, the benches for both the Lions and their opponents were on the outfield side of the field. Well into the 1990s—some two decades after the Lions left—a "possession" symbol, with its light bulbs, for football games could still be seen on the auxiliary scoreboards.

In the late 1960s, the city of Pontiac and its community leaders made a presentation to the Metropolitan Stadium Committee of a 155-acre (0.63 km2) site on the city's east side at the intersection of M-59 and Interstate 75 (I-75). Initially, a dual stadium complex was planned that included a moving roof that was later scrapped due to high costs and the lack of a commitment from the Detroit Tigers baseball franchise. In 1973, ground was broken for a stadium to exclusively house the Detroit Lions.[10] The Metropolitan Stadium Committee voted unanimously for the Pontiac site.

Other events

1939 saw a major boxing fight being held at the stadium, when Joe Louis defended the world Heavyweight title with an eleventh round knockout of Bob Pastor.[11]

On Friday, October 5, 1951, the University of Notre Dame played the University of Detroit at Briggs Stadium before a capacity crowd of 52,371. It was the first Notre Dame football game to be played at night.[12] The Fighting Irish won, 40-6.[13]

Northern Irish professional soccer club Glentoran called the stadium home for two months in 1967. The Glens, as the team from Belfast are known played under the name Detroit Cougars as one of several European teams invited to the States during their off/close season to play in the United Soccer Association.

Notable moments and facts

When Ty Cobb played at Tiger Stadium, the area of dirt in front of home plate was kept wet by the groundstaff in order to slow down Cobb's bunts and cause opposing infielders to slip as they fielded them.[14] The area was nicknamed "Cobb's Lake".[14]

On July 13, 1934, Babe Ruth hit his 700th career home run. As noted in Bill Jenkinson's The Year Babe Ruth Hit 104 Home Runs, the ball sailed over the street behind the then-single deck bleachers in right field, and is estimated to have traveled over 500 feet (150 m) on the fly. On July 18, 1921, when he hit what is believed to be the verifiably longest home run in the history of major league baseball. It went to straightaway center, as many of Ruth's longest homers did, easily clearing the then-single deck bleacher and wall, landing almost on the far side of the street intersection. The distance of this blow has been estimated at between 575 and 600 feet (180 m) on the fly.

On May 2, 1939, an ailing New York Yankees first baseman Lou Gehrig voluntarily benched himself at Briggs Stadium, ending a streak of 2,130 consecutive games. Due to the progression of the disease named after him, it was the final game in his career.

The stadium hosted the 1941, 1951 and 1971 MLB All-Star Games. All three games featured home runs. Ted Williams won the 1941 game with an upper deck shot. The ball was also carrying well in the 1951 and 1971 games. Of the many homers in those games, the most often replayed is Reggie Jackson's literally towering drive to right field that hit so high up in the light tower that the TV camera lost sight of it, until it dropped to the field below. Jackson dropped his bat and watched it sail, seemingly astonished at his own power display.

On April 7, 1986, Dwight Evans hit a home run on the first pitch of the Opening Day game, for the earliest possible home run in an MLB season (in terms of innings and at bats, not dates).

Tiger Stadium saw exactly 11,111 home runs, the last a right field, rooftop grand slam by Detroit's Robert Fick as the last hit in the last game played there.[15]

There were over 30 home runs hit onto the right field roof over the years. It was a relatively soft touch compared to left field, with a 325-foot (99 m) foul line and with a roof that was in line with the front of the lower deck. In left field, it was 15 feet (4.6 m) farther down the line, and the roof was set back some distance. Only four of the game's most powerful right-handed sluggers (Harmon Killebrew, Frank Howard, Cecil Fielder and Mark McGwire) reached the left field rooftop. In his career, Norm Cash hit four home runs over the Tiger Stadium roof in right field and is the all-time leader.[16]

The final game

On September 27, 1999, the final Detroit Tigers game was held at Tiger Stadium; an 8–2 victory over the Kansas City Royals, capped by a late grand slam by Robert Fick. Fick's 8th inning grand slam hit the right field roof and fell back onto the playing field, where it was retrieved by Tigers personnel. Fick's blast was the final hit, home run and RBI in Tiger Stadium's history. The whereabouts of the ball are currently unknown. Following the game, an emotional ceremony with past and present Tigers greats was held to mark the occasion. The Detroit Tigers moved to the newly constructed Comerica Park for their 2000 season, leaving Tiger Stadium unused.

After baseball

On July 24, 2001, the day Detroit celebrated its 300th birthday, a Great Lakes Summer Collegiate Game between the Motor City Marauders and the Lake Erie Monarchs was played at Tiger Stadium. It was in an effort by a local sports management company that is seeking to bring a minor league franchise to Detroit in the Frontier League.

On Saturday, February 4 and Sunday, February 5, 2006, a tent on Tiger Stadium's field played host to Anheuser-Busch's Bud Bowl 2006. Among performers at the nightclub-style event was Snoop Dogg.[17] After several years out of the public eye, the Bud Bowl event led the Detroit Free Press to make the interior of the stadium the feature of a photo series on February 1, 2006.[18] These photos showed the stadium's deteriorating condition, which included trees and other vegetation growing in the stands. Anheuser-Busch promoted the advertising event as Tiger Stadium's Last Call.

In early 2006, the feature-length documentary Stranded at the Corner was released. Funded by local businessman and ardent stadium supporter Peter Comstock Riley, and directed by Gary Glaser, it earned solid reviews and won three Telly awards and two Emmy awards for the film's writer and co-producer, Richard Bak (a local journalist and the author of two books about the stadium). It was also shown at the inaugural National Baseball Hall of Fame Film Festival, held in Cooperstown, New York, November 2006.[19]

Demolition

Many private parties, non-profit organizations and financiers expressed interest in saving the ballpark after its closure. These included multiple proposals to convert the stadium into mixed-use condominiums and residential lofts overlooking the existing playing field. By 2006, however, demolition appeared inevitable when then-Detroit Mayor Kwame Kilpatrick announced the stadium would be razed the following year.

In December 2006, the Detroit Economic Growth Corporation (DEGC) hosted a walk-through for potential bidders on a project to remove assets from Tiger Stadium that qualified as "memorabilia" and to sell these items in an online auction hosted by Schnieder Industries.[20] Once the stadium was stripped of seating, signage and other items classified as non-structural (i.e. support columns) which would yield income for the City of Detroit at auction, demolition would commence.

The DEGC awarded the demolition contract on April 22, 2008, with the speculation that demolition revenue would come from the sale of scrap metal and not from the City of Detroit. Wrecking crews commenced operations on June 30, in the wall behind the old bleacher section facing I-75 near the intersection of Trumbull Avenue. The demolition of the left field stands opened up the stadium's interior to view for the first time in decades on July 9, 2008 (the ballpark had been double-decked since the late 1930s).[21]

After a hiatus wherein various plans to preserve portions of the stadium were considered,[22][23][24][25][26] demolition was completed in June 2009.

Redevelopment

During the summer of 2010, a group calling itself "The Navin Field Grounds Crew" began maintaining the playing field and hosting vintage baseball, youth baseball, and softball games at the site.[27] There is also a sign on the enclosing fence labelling the site "Ernie Harwell Park",[28] and the name is also used to refer to the site on OpenStreetMap and other online mapping services based on it.

On December 16, 2014, a $33 million project by Larson Realty Group to redevelop the old Tiger Stadium site was approved by Detroit's Economic Development Corporation. Development plans include a four-story building along Michigan Avenue with about 30,000 square-feet of retail space and 102 residential property rental units, each averaging 800 square feet. Along Trumbull Avenue, 24 town homes are planned for sale. Detroit's Police Athletic League (PAL) headquarters will relocate to the site and maintain the field. PAL will build its new headquarters and related facilities on the western and northern edges of the site while preserving the historic playing field for youth sports, including high school and college baseball.[29][30][31]

Films and television

The stadium was depicted in Disney's award-winning Tiger Town, a 1983 made-for-television baseball film written and directed by Detroit native, Alan Shapiro, starring Roy Scheider, Sparky Anderson, Ernie Harwell and Mary Wilson, and (as Briggs Stadium) in the 1980 feature film Raging Bull where the stadium was the site of two of Jake LaMotta's championship boxing matches. Tiger Stadium was also seen in the film Hardball starring Keanu Reeves, Renaissance Man with Danny DeVito and in the aforementioned film 61*, where it "played" the part of Yankee Stadium as well as itself.

In the summer of 2000, the HBO movie 61* was filmed in Tiger Stadium. The film dramatized the efforts of New York Yankees teammates Mickey Mantle and Roger Maris during the 1961 season to break fellow Yankee Babe Ruth's single-season home run record of 60. (Coincidentally, Roger Maris hit his first home run of the 1961 season at Tiger Stadium.) For the film, Tiger Stadium was repainted to resemble Yankee Stadium in 1961.

During the very last days in which part of Tiger Stadium was still standing, scenes for the film, Kill the Irishman, depicting the old Cleveland baseball stadium were shot at the stadium, extending for a day (demolition continued the day after the single day shoot at the stadium on June 5, 2009) the life of Tiger Stadium.[32]

The pilot of the HBO series Hung featured the stadium's demolition in its opening scene.[33]

References in popular culture

- Sports Illustrated featured a poll of major league baseball players asking which stadium is the favorite to play in. Tiger Stadium usually placed within the top 5.

- Green Cathedrals quoted Joe Falls, sportswriter for The Detroit Free Press, who used to say that there was a sign over the visitors' clubhouse entrance that read "No visitors allowed".

- In Douglass Wallop's 1954 novel The Year the Yankees Lost the Pennant (which inspired the Broadway musical Damn Yankees), Joe Hardy makes his debut for the Washington Senators team during a doubleheader at Tiger Stadium, hitting a game-winning home run in each game. During batting practice he hits one ball over the right field roof.

- Artist Gene Mack, who drew a series of pictures of Major League parks, mentioned a bone that Ty Cobb used to "bone" his bats as part of his care for them. The bone stayed in the clubhouse after he left the Tigers in 1926 and, indeed, after he retired in 1928. In his autobiography, he noted that the last time he visited the Tigers' clubhouse (he died in 1961), that bone was still in use. As of 1999, when the Tigers completed their tenure at Tiger Stadium, a bone remained a fixture in the clubhouse on a table next to the bat rack.

- In the music video for rapper Eminem's song "Beautiful", Eminem can be seen walking through the stadium, showing the destruction of the stadium.

- In episode 9 of the second season of the HBO TV show Hung the main character "Ray" randomly and incoherently laments on the demolition of Tiger Stadium blaming it on the desire for a "glass box" or something. The scene was filmed on the remains of Tiger Stadium's field, in the area on and around the pitcher's mound as well as just outside the field's gates.

Seating Capacity

The seating capacity went as follows for baseball:

- 23,000 (1912–1922)[34]

- 30,000 (1923–1936)[35]

- 36,000 (1937)[35]

- 58,000 (1938–1960)[36]

- 52,904 (1961)[37]

- 52,850 (1962)[38]

- 53,089 (1963–1968)[39]

- 54,226 (1969–1977)[40]

- 53,676 (1978–1979)[41]

- 52,067 (1980)[42]

- 52,687 (1981)[43]

- 52,806 (1982–1988)[44]

- 52,416 (1989–1996)[45]

- 46,945 (1997–2008)[46]

The seating capacity went as follows for football:

Photo gallery

An empty Tiger Stadium in January 2005

An empty Tiger Stadium in January 2005 Tiger Stadium showing signs of neglect in 2006.

Tiger Stadium showing signs of neglect in 2006. Tiger Stadium with facade lettering removed in November 2007.

Tiger Stadium with facade lettering removed in November 2007.- of visitors' bullpen and right field from lower deck, November 2007.

- Tiger Stadium with seats removed in November 2007.

Abandoned in April 2008; Tigers now play in Comerica Park.

Abandoned in April 2008; Tigers now play in Comerica Park. Demonstration against a School Amendment at Navin Field in 1920

Demonstration against a School Amendment at Navin Field in 1920

References

- ↑ Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Community Development Project. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. Retrieved October 21, 2016.

- ↑ "Bennett Park/Navin Field/Briggs Stadium/Tiger Stadium". Detroit1701. Retrieved May 10, 2014.

- ↑ "NPS Focus". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. Retrieved January 8, 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 "Detroit PAL hits goal for HQ at Tiger Stadium site"; by John Gallagher; Detroit Free Press; February 2, 2016

- ↑ Detroit Tigers, Past Detroit Tigers Venues

- ↑ "Tiger Stadium Damaged By Fire," United Press International, Wednesday, February 2, 1977.

- ↑ jw1223117 | Flickr - Photo Sharing

- ↑ jw121789 | Flickr - Photo Sharing

- ↑ Rangers Ballpark in Arlington

- ↑ Pontiac Silverdome History and Conception: Conception of the Pontiac Silverdome

- ↑ http://boxrec.com/media/index.php?title=Fight:19824

- ↑ http://archives.chicagotribune.com/1951/10/05/page/47/article/irish-to-play-detroit-in-1st-night-contest

- ↑ http://archives.chicagotribune.com/1951/10/06/page/29/article/notre-dame-routs-detroit-40-to-6

- 1 2 Dickson, Paul (1989). The Dickson Baseball Dictionary. United States: Facts on File. p. 105. ISBN 0816017417.

- ↑ Box Score of Game played on Monday, September 27, 1999 at Tiger Stadium

- ↑ The Final Season, p. 85, Tom Stanton, Thomas Dunne Books, An imprint of St. Martin's Press, New York, 2001, ISBN 0-312-29156-6

- ↑ ESPN - A six-pack to go at Tiger Stadium's hallowed ground - MLB

- ↑ Photo Gallery: Tiger Stadium: Party host

- ↑ Preserve Tiger Stadium

- ↑ Welcome to TigerstadiumSale Archived October 1, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Tiger Stadium Field, Foul Poles to Be Saved". ESPN. July 10, 2008. Retrieved May 10, 2014.

- ↑ "Partial Demolition of Tiger Stadium Almost Done". MLive Detroit. November 4, 2009. Retrieved May 10, 2014.

- ↑ Gorchow, Zachary (October 10, 2008). "Deal Stalls Tiger Stadium Demolition". Detroit Free Press. Retrieved May 10, 2014.

- ↑ Gorchow, Zachary. "Remnants of Tiger Stadium Safe – For Short Time". Detroit Free Press. Retrieved May 10, 2014.

- ↑ Leubsdorf, Ben (June 2, 2009). "So Long: Detroit Board OKs Leveling Tiger Stadium". USA Today. Retrieved May 25, 2010.

- ↑ Beck, Jason (June 8, 2009). "Demolition of Tiger Stadium Resumes". Major League Baseball Advanced Media. Retrieved May 10, 2014.

- ↑ Saving Tiger Stadium, James Hughes, grantland.com, April 7, 2014

- ↑ http://img.tapatalk.com/d/12/10/23/8yjagemu.jpg

- ↑ Austin, Dan (December 16, 2014). "Renderings reveal future of Tiger Stadium, field". Detroit Free Press. Retrieved December 16, 2014.

- ↑ Aguilar, Louis (December 16, 2014). "Key approval given to Tiger Stadium plans". Detroit News. Retrieved December 16, 2014.

- ↑ Bertha, Mike (December 16, 2014). "Who wants to live at Tiger Stadium? Development deal to include houses, preservation of field". MLB. Retrieved December 16, 2014.

- ↑ Watson, Ursula (June 5, 2009). "Tiger Stadium's Last Glory: Bit Part in Film". The Detroit News. Retrieved June 5, 2009.

- ↑ Johnson, Reed (June 28, 2009). "'Hung' Speaks to People Disillusioned with the American Dream". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 25, 2010.

- ↑ "Most Popular". CNN. Retrieved November 4, 2011.

- 1 2 "Past Detroit Tigers Venues". Major League Baseball Advanced Media. Retrieved November 27, 2011.

- ↑ "Mickey Coachrane Fired As Manager of Detroit Tigers". Meriden Record. August 8, 1938. Retrieved November 27, 2011.

- ↑ "Detroit Tigers 1961 Guide" (PDF). Major League Baseball Advanced Media. 1961. Retrieved November 27, 2011.

- ↑ "Detroit Tigers 1962 Guide" (PDF). Major League Baseball Advanced Media. 1962. Retrieved November 27, 2011.

- ↑ "Detroit Tigers 1963 Guide" (PDF). Major League Baseball Advanced Media. 1963. Retrieved November 27, 2011.

- ↑ "Detroit Tigers 1969 Guide" (PDF). Major League Baseball Advanced Media. 1969. Retrieved November 27, 2011.

- ↑ "Detroit Tigers 1978 Guide" (PDF). Major League Baseball Advanced Media. 1978. Retrieved November 27, 2011.

- ↑ "Detroit Tigers 1980 Guide" (PDF). Major League Baseball Advanced Media. 1980. Retrieved November 27, 2011.

- ↑ "Detroit Tigers 1981 Guide" (PDF). Major League Baseball Advanced Media. 1981. Retrieved November 27, 2011.

- ↑ "Detroit Tigers 1982 Guide" (PDF). Major League Baseball Advanced Media. 1982. Retrieved November 27, 2011.

- ↑ "American League Park Directory". Baseball Digest. Lakeside Publishing Company. 55 (4): 126. April 1, 1996.

- ↑ "American League Park Directory". Baseball Digest. Lakeside Publishing Company. 58 (4): 92. April 1, 1999.

- ↑ "Detroit Mauls Bears, 28–14". The Gadsden Times. October 3, 1970. Retrieved November 27, 2011.

- ↑ Detroit Lions

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tiger Stadium (Detroit). |

- Aerial Views, Demolition of Tiger Stadium 2008 - 2009

- A documentary on the battle to save Tiger Stadium

- Navin Field Information Site

- Past Tigers Venues

- Tiger Stadium Demolition News & Videos

- USGS aerial photo

- Overhead images of Tiger Stadium before and after demolition

| Events and tenants | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Bennett Park |

Home of the Detroit Tigers 1912–1999 |

Succeeded by Comerica Park |

| Preceded by University of Detroit Stadium |

Home of the Detroit Lions 1938–1974 |

Succeeded by Pontiac Silverdome |

| Preceded by Sportsman's Park Comiskey Park Riverfront Stadium |

Host of the All-Star Game 1941 1951 1971 |

Succeeded by Polo Grounds Shibe Park Atlanta Stadium |