Timeline of First Nations history

1

| Aboriginal peoples in Canada |

|---|

|

History

|

|

Politics

|

|

Culture

|

|

Demographics

|

|

Religions |

|

Index

|

|

Wikiprojects Portal

WikiProject

First Nations Inuit Métis |

The history of First Nations is a prehistory and history of Canada's founding peoples from the earliest times to the present with a focus on First Nations. The pre-history settlement of the Americas is subject of ongoing debate as First Nations oral history, combined with new methodologies and technologies used by archaeologists, linguists, and other researchers, produce new and sometimes conflicting, evidence.

75,000-15,000 BP

| Year | Date | Event |

|---|---|---|

| c. 73,000-13,000 BP | Ice Age There was a land bridge across the Bering Strait.[1] Sioux scholar, author and historian Deloria argued in his 1995 book Red Earth, White Lies[2] that the Bering Strait Land Bridge never existed, and that the ancestors of the Native Americans had not migrated to the Americas over such a land bridge, as has been claimed by most archaeologists, anthropologists, linguists and other scholars. Rather, he asserted that the Native Americans may have originated in the Americas, or reached them through transoceanic travel, as some of their creation stories suggested.[3]:233[4]:155[5] The results of a multiple-author suudy by Danish, Canadian and American scientists published in Nature in February 2016 revealed that "the first Americans, whether Clovis or earlier groups in unglaciated North America before 12.6 cal. kyr BP", are "unlikely" to "have travelled to North America from Siberia via the Bering land bridge[6] "via a corridor that opened up between the melting ice sheets in what is now Alberta and B.C. about 13,000 years ago" as many anthropologists have argued for decades.[7] The lead author, University of Copenhagen a PhD student Mikkel Pedersen explained, "The ice-free corridor was long considered the principal entry route for the first Americans... Our results reveal that it simply opened up too late for that to have been possible."[7] |

50,000 BP

| Year | Date | Event |

|---|---|---|

| 50,000 BP | Humans reached "Australia across a wide stretch of open sea by at least 30 000 years ago, and that as long as 200 000 years ago the Palaeolithic (Old Stone Age) occupants of Europe were living under extremely cold environmental conditions and may have had watercraft capable of crossing the Strait of Gibraltar. It is theoretically possible, therefore, that humans could have reached North America from northeast Siberia at any time during the past 100, 000 years."[8] |

40,000 BP

| Year | Date | Event |

|---|---|---|

| 40,000 BP | The earliest record of Rangifer tarandus caribou[9] (which includes five subspecies:boreal woodland caribou, barren-ground caribou) in North America is from a 1.6 million year old tooth found in the Yukon Territory; other early records include 45,500-year-old cranial fragment from the Yukon and a 40,600-year-old antler from Quebec (Gordon 2003). The ancestral origins of caribou prior to the last glaciation (Wisconsin), which occurred approximately 80,000 to 10,000 years ago, are not well understood, however, during the last glaciation it is known that caribou were abundant and distributed in non-glaciated refugia both north and south of the Laurentide ice sheet. |

30,000–20,000 BP

| Year | Date | Event |

|---|---|---|

| 30,000–20,000 BP | Mammoth bones, believed to have been chipped by humans, are found at the Yukon's Bluefish Caves[10][11][12] | |

| 30,000–20,000 BP | In 2004, Albert Goodyear of the South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology announced radiocarbon dating of a bit of charcoal found in the Topper Site that preceded Clovis culture, near Allendale County, South Carolina.[13] However, these deposits may have been made by forest fires.[13]

(Note: The dates given for the Old Crow and Topper digs have not been completely accepted by the archaeology community).[14][15] | |

| 30,000–20,000 BP | Ice-free corridor running north and south through Alberta and the continental glacier called Laurentide ice sheet. Introduced by geologists in the 1950s when stone tools were found in the Grimshaw, Bow River and in Lethbridge Alberta, under glacial sand and gravel; they are believed to be pre-glacial and may indicate nomadic humans occupied the area.[1] A child's skull found in 1961 near Taber, Alberta is believed to be of one of the oldest inhabitants discovered in Alberta.[16]

(Note: The conclusions reached in Alberta on dates have not been accepted by the entire archaeology community.)[17] | |

| 30,000–20,000 BP | A DNA laboratory in Cambridge, MA claimed that humans entered the Americas around 25,000 years ago.[18] Other geneticists have variously estimated that peoples of Asia and the Americas were part of the same population from about 21,000 to 42,000 years ago.[19] | |

| 30,000–20,000 BP | Siberian mammoth hunters were believed to have penetrated far into the Arctic where ice-free corridors north during the time are believed found. Theory first introduced by geologists in the late 1970s when core samples indicate the ice is no older than 17,000 years old.[20] |

Paleo-Indians period

| Year | Date | Event |

|---|---|---|

| 20,000 BP | Radiocarbon dating of a caribou bone flesher found by Lord and Harington in the Old Crow River Basin placed it at late Holocene period.[21] Arctic archaeologist William N. Irving (1927-1987),[10] working closely with local Old Crow residents, focused his research on Crow basin and the Bluefish caves in the surrounding mountains (1966-1983). Old Crow Flats and Bluefish Caves are some of the earliest known sites of human habitation in Canada.[22] The Old Crow Flats and basin was one of the areas in Canada untouched by glaciations during the Pleistocene Ice ages, thus it served as a pathway and refuge for ice age plants and animals.[23] |

12,000 BP

| Year | Date | Event |

|---|---|---|

| 12,000 BP | According to R. Cole Harris, prehistoric trade routes map show that Knife River silica was traded in all directions including the route north to what is now Canada.[24] | |

| 12,000-11,000 BP | According to internationally renowned archaeologist George Carr Frison Bison occidentalis and Bison antiquus, an extinct sub-species of the smaller present-day bison, survived the Late Pleistocene period, between about 12,000 and 11,000 years ago, dominated by glaciation (the Wisconsin glaciation in North America), when many other megafauna became extinct.[25] Plains and Rocky Mountain First Nations depended on these bison as their major food source. Frison noted that the "oldest, well-documented bison kills by pedestrian human hunters in North America date to about 11,000 years ago."[26] |

11,000 BP

| Year | Date | Event |

|---|---|---|

| 11,000 BP | The Crowsnest Pass is the richest archaeological zone in the Canadian Rocky Mountains. The oldest relics are stone tools found on a rock ridge outside Frank, Alberta, from the Clovis culture, 11,000 years before present. Other sites include chert quarries on the Livingstone ridge dating back to 1000 BC.[27] | |

| 11,000 BP | Archaeological evidence of different cultural campsites on Asian and North American sides of Beringia.[1] | |

| 11,000 BP | The Folsom tradition, also known as Folsom culture, or Lindenmeier culture, replaced previous Clovis ways of life.[28] | |

| 11,000 BP | 6,000 BP | The Plano cultures existed in Canada during the Paleo-Indian or Archaic period between 11,000 BP and 6,000 BP. The Plano cultures originated in the plains, but extended far beyond, from the Atlantic coast to British Columbia and as far north as the Northwest Territories.[29][30] "Early Plano culture occurs south of the North Saskatchewan River in Saskatchewan and in the foothills of the Rocky Mountains north to the Peace River Valley of Alberta and adjacent British Columbia. At this time, most of Manitoba was still covered by Glacial Lake Agassiz and associated glacial ice."[29] The Plano cultures are characterised by a range of unfluted projectile point tools collectively called Plano points and like the Folsom people generally hunted bison antiquus, but made even greater use of techniques to force stampedes off of a cliff or into a constructed corral. Their diets also included pronghorn, elk, deer, raccoon and coyote. To better manage their food supply, they preserved meat in berries and animal fat and stored it in containers made of hides.[31][32][33] "Early Plano culture occurs south of the North Saskatchewan River in Saskatchewan and in the foothills of the Rocky Mountains north to the Peace River Valley of Alberta and adjacent British Columbia. At this time, most of Manitoba was still covered by Glacial Lake Agassiz and associated glacial ice."[29] Bison herds were attracted to the grasslands and parklands in the western region. Around 9,000 B.P. as retreating glaciers created newly released lake regions, the expansion of plant and animal communities expanded north and east, and tundra caribou and boreal woodland caribou replaced bison as the major prey animal.[29] |

| 11,200 | 10, 500 BP | Archaeological evidence, fluted spear points used for hunting bison and caribou found across Canada[1] |

| 11,000 BP | Charlie Lake Cave Archaeological site report HbRf-39 states: "...the importance of this site lies in its exceptionally long and continuous cultural, sedimentary and faunal sequence, which seems to have accumulated steadily without erosional episodes for at least 11,000 years.[34] The lowest (earliest) level containing stone artifacts, including a fluted point, six retouched flakes and a small stone bead has been dated to 10,770±120 years BP.[35] With an average age of about 10,500, component 1 at Charlie Lake cave[36] near Fort St. John is the oldest dated evidence of man in the province, and one of the oldest in Canada.;[36][37][38] The Dane-zaa First Nation (Beaver) are the descendants of these early people.;;[39][40][38][34] Driver argues that "Charlie Lake Cave is situated right in the middle of the ice-free corridor region. However, evidence from the site suggests that people may not have moved from north to south down the corridor, but instead may have moved from south to north, following herds of bison. This is suggested from DNA analysis of the bison remains, which indicates that some of the bison found at Charlie Lake originated in the southern regions of the North American continent. In addition, the fluted point found at Charlie Lake Cave is similar to points found at the Indian Creek and Mill Iron sites in Montana. These sites were occupied before Charlie Lake Cave, which suggests that perhaps the tool technology was developed in the south, and brought to Charlie Lake Cave at a later time when the tool makers and their descendants moved north." | |

| 11,000 BP | Salmon-based Northwest Coast culture established.[1] | |

| 11,000 BP | Prehistoric trade routes map show that Batza Tena obsidian was at the center of trade routes by 11000 BP.[24]Obsedian was valued for it cutting edge and its beauty. Archaeological sites revealed obsidian was traded far from its place of origin.[41] | |

| 11,000 BP | "Archaeological records confirm that there were Aboriginal campsites in New Brunswick dating back approximately 11,000 years."[42][43] | |

| 11, 000 years ago | Paleo-indians "reached Maine by over 11,000 years ago and Debert, Nova Scotia not many years later."[44][45][46][47]:3 The Debert Palaeo-Indian Site was designated a National Historic Site of Canada in 1974.[48] |

10,500 BP

| Year | Date | Event |

|---|---|---|

| 10,500 BP | 7,750 BP | The Early Precontact Period[49] (10,500–7,750 years ago) is is characterized by archaeological complexes containing stone projectile points of triangular, fluted, lanceolate, or stemmed forms, presumably used with throwing and stabbing spears. At least five cultural complexes occur in Alberta, including Clovis and its derivatives, Windust, Cascade, Cody, and Plains-Mountain. These groups appear to have been primarily big-game hunters who often moved over vast areas during their annual rounds while visiting preferred resources. Their stone tools can be found great distances from the sources of their raw material. |

| 10,500 BP | Prehistoric trade routes map show that Wyoming obsidian was at the center of trade routes from 10500 BP to AD 500 including the route north to what is now Canada.[24] | |

| 10,500 BP | Dane-zaa The Dane-zaa (ᑕᓀᖚ, also spelled Dunneza, or Tsattine, and historically often referred to as the Beaver tribe by Europeans) are a First Nation of the large Athapaskan language group; their traditional territory is around the Peace River of the provinces of Alberta and British Columbia, Canada. Recent archaeological evidence establishes that the area of Charlie Lake north of Fort St John has been continuously occupied for 10,500 years by varying cultures of indigenous peoples.[50][51][52] | |

| 10,500 BP | "Other sites in the province from this time period include the Charlie Lake Cave site near Fort St. John, dating to 10,500 BP."[53]:11 |

10,000 BP

| Year | Date | Event |

|---|---|---|

| 10,000 BP | In a study published in Nature in 2016, scientists argued that by 10,000 years ago, the ice-free corridor in what is now Alberta and B.C "was gradually taken over by a boreal forest dominated by spruce and pine trees" and that "Clovis people likely came from the south, not the north, perhaps following wild animals such as bison."[7][6] | |

| 10,000 BP | The inhabitants of Quilá Naquitz cave in Oaxaca, Mexico, cultivated and initially domesticated Cucurbita Pepo between 10,000 and 8000 calendar years ago (9000 to 7000 carbon-14 years before the present). This "predates maize, beans, and other directly dated domesticates in the Americas by more than 4000 years."[54] | |

| 10,000 BP | The site of what is now Banff National Park, Alberta, Canada, has been occupied by people for 10,000 years. Over 700 archaeological sites (both pre-contact and historic) have been recorded. These sites contain artifacts, evidence of the presence of Aboriginal campsites, butchering sites, quarries, mining towns and historical dumps.[55] | |

| 10,000 BP | 8,000 BP | The Stó:lo called their traditional territory in the Fraser River Valley,S'ólh Téméxw. The first traces of people living in the Fraser Valley date from 8,000 to 10,000 years ago. There is archaeological evidence of a settlement in the lower Fraser Canyon(called "the Milliken site") and a seasonal encampment ("the Glenrose Cannery site") near the mouth of the Fraser River.[56] |

| 10,000 BP | The Ediza quarry was the oldest of several obsidian quarries in British Columbia. Ediza obsidian was in use from 10,000 BP until European contact.[1][24] Fladmark argued that trade in that region of BC is at least 10,000 years old.[57] | |

| 10,000 BP | Human occupation in Prince George, British Columbia dates to 9,000 to 10,000 BP.[53]:11 |

9,700 BP

| Year | Date | Event |

|---|---|---|

| 9,700 BP | Human occupation in a site near Namu on Vancouver Island, dates to 9,700 BP.[53]:11 |

9,000 BP

| Year | Date | Event |

|---|---|---|

| 9,000 BP | 7,000 BP | During the Holocene climatic optimum or Hypsithermal period, about "9000 years ago the climate of western North America started becoming hotter and drier before reaching a maximum warmth and dryness about 7000 years ago." Archaeological sites from this period in Alberta include Boss Hill, Bitteroot, Mummy Cave, at sites near Calgary, Crowsnest Pass, and in the Cypress Hills (Canada) and Porcupine Hills, on the Manitoba Escarpment,[58] which was the shoreline of the glacial Lake Agassiz.[59] |

| 9,000 BP | The Milliken site in the Fraser Canyon dated to 9,000 BP.[53]:11 |

8,500 BP

| Year | Date | Event |

|---|---|---|

| 8,500 BP | The Paskapoo Slopes of Broadcast Hill as well as in Tuscany, downtown Calgary, Alberta and Hawkwood, are the oldest archaeological sites in the city of Calgary, dating back to about 8,500 radiocarbon years BP.[60] In "pre-contact times, First Nation peoples used the area extensively as the high escarpment ridge offered unobstructed views of the Bow River Valley below and the prairies beyond. The river banks were used as winter camps."[61] |

8,250 BP

| Year | Date | Event |

|---|---|---|

| 8,250 BP | Gore Creek site near Kamloops dates to 8250 BP.[62] The early occupants of the area were likely fairly mobile hunter-gatherers due to the lack of dependable resources.[53]:11 |

8,000 BP

| Year | Date | Event |

|---|---|---|

| 8,000 BP | Prehistoric trade routes map show that Keewatin silica was at the center of trade routes.[24] |

6,800 BP

| Year | Date | Event |

|---|---|---|

| 6,800 years ago | A large volcano erupted in the United States depositing volcanic ash over much of western Canada. Archaeologists use the layer of Mazama ash to date sites. |

6,000 BP

| Year | Date | Event |

|---|---|---|

| 6,000 years ago | The flat pink granite of what is now Whiteshell Provincial Park in southeast Manitoba along the Manitoba-Ontario boundary, was used for petroform making by First Nation peoples. There is also archaeological evidence of ancient copper trading going east to Lake Superior, prehistoric quartz mining, and stone tool making in the area. For thousands of years aboriginal peoples - Ojibway, or Anishinaabe various other groups before them, used the area for harvesting wild rice, hunting, fishing, trade, and dwelling. The Whiteshell Natural History Museum opened in 1960. The name of the park is derived from the cowrie shells that were used in ceremonies by the Ojibway, Anishinaabe, and Midewiwin. |

5,000 BP

| Year | Date | Event |

|---|---|---|

| 5,000 years ago | Porcupine Hills/Oldman River basin pattern of bison driving, trapping and processing dating back over the past five thousand years or more, is characterized by the use of escarpments, slopes, benches and ravines for trapping and processing bison. The bison were gathered from the grazing lands in the uplands to the south and west and moved by a system of drive lanes to preferred killing and processing locales along Paskapoo Slopes. Archaeologist Brian O.K. [63] The northern extension of the Porcupine Hills/Oldman River basin pattern has been identified in Calgary, Alberta where forty-nine archaeological pre-contact Native archaeological sites were found in the East Paskapoo Slopes. These sites ranged in type from kill/processing sites of buffalo to camps and sweat pits.[64] First Nation peoples used the area extensively as the high escarpment ridge offered unobstructed views of the Bow River Valley below and the prairies beyond. The river banks were used as winter camps. As well, the steep cliffs provided ideal conditions for the buffalo jump, a unique method of hunting bison that is similar in complexity to the UNESCO World Heritage Site Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump.[65] | |

| 5,000 years ago | "Oxbow technology originally entered the Canadian grasslands 5000 years ago from both the southwestern foothills and the southeastern prairies. The development of adaptive strategies involving seasonal use of the boreal forest and parkland zones allowed the eventual full-time colonization of these zones by Oxbow groups."[66] |

4,500 BP

| Year | Date | Event |

|---|---|---|

| 4,500 BP | "Palaeoeskimo peoples are believed to have a common ancestry based in northeast Asia and Alaska beginning about 4500 B.P." "Independence I, which is found in portions of Greenland and Labrador from 4000 to 3500 B.P."[67] | |

| 4,500 BP | "Salish woven objects have been excavated by archaeologists at Musqueam. In the same area weaving tools have been found.[68] |

4,300 BP

| Year | Date | Event |

|---|---|---|

| 4,300 BP | In 1997, in the Yukon, a 4,300-year-old dart shaft was discovered as the ice receded.[69] |

4,000 BP

| Year | Date | Event |

|---|---|---|

| 4,000 BP | The oldest dated occupation in the area of what is now known as L'Anse aux Meadows, Newfoundland was 6,000 years ago. Prior to European settlement, there is evidence of different aboriginal occupations in the area. None was contemporaneous with the Norse occupation. The most prominent of these earlier occupations were by the Dorset people, who predated the Norse by about 200 years.[70] |

3,000 BP

| Year | Date | Event |

|---|---|---|

| 3,000 BP | Human sites have been found on the Slate Islands (Ontario), Slate Island, located in what is now known as northern Lake Superior, dating to about 3000 BP.[71] | |

| 3,000 BP | Pukaskwa Pits are depressions left by early inhabitants, probably Algonkian people, between 3000 BP and 500 BP.[72] The larger pits or "lodges" may have been seasonal dwellings with domed coverings, hunting blinds or caches for food. The smaller pits may have been used to cook food or smoke fish.[72] Ojibwe, voyageurs, fur traders, prospectors, fishermen and loggers came later.[73] |

2,400 BP

| Year | Date | Event |

|---|---|---|

| 2,400 years ago | Tom Andrews, working closely with the Sahtúot’ine or Mountain Dene and using their experience and tradition knowledge (TEK), found 2400-year-old spear throwing tools in the Mackenzie Mountains. The spear and "1000-year-old ground squirrel snare, and bows and arrows dating back 850 years" were used by the Mountain Dene's ancestors.[69] |

1000 BP

| Year | Date | Event |

|---|---|---|

| 1,050 BP | Huron-Petun, or (Wendat-Tionontaté), Iroquoian-speaking agriculturalists occupied south-central Ontario from 1050 BP to 300 BP.[74][75] |

951 BP

| Year | Date | Event |

|---|---|---|

| c. 1000-1500 AD | Norse settlement. Greenland Norse trade.[24] |

950 BP - 450 BP

| Year | Date | Event |

|---|---|---|

| c. 1000 AD | 1500 AD | Two large 15th-century Huron ancestral villages surrounded by palisade, Draper Site and the Mantle Site have been excavated. The Mantle Site had more than 70 longhouses.[76] They later moved from there to their Georgian Bay historic territory to their villages such as, Ratcliff site, the Aurora or Old Fort site where they Champlain encountered in 1615.[77] |

450 BP

| Year | Date | Event |

|---|---|---|

| 1500 AD | 1550 AD | The Seed-Barker archaeological site is a 16th-century Iroquois village on the Humber River in Vaughan. It has been used as a summer school field trip site since 1976 by the Boyd archaeological field summer school for high school students. The school is sponsored by the York Region district school board in co-operation with the Royal Ontario Museum and the Toronto and Region Conservation Authority (TRCA). In 1895 a local farmer began finding Iroquoian artifacts in the area. In 1895 Roland Orr recognized the classic ecological features favoured by the Iroquoian people for their villages: floodplains along a river, an easily defensible plateau and nearby forests. The Iroquois used the floodplains to plant the three main agricultural crops: squash, maize (corn), and climbing beans,:1 using a companion planting technique known as the Three Sisters. In the 1950s University of Toronto professor, Norman Emerson, and the students excavated artifacts from the Seed-Baker site. Since 1975 more than a million artifacts were discovered and nineteen longhouses were excavated. [78] |

16th century

| Year | Date | Event |

|---|---|---|

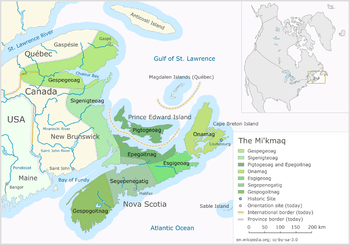

| c. 1536 AD | 1632 | Documented accounts of Basques whalers in the Strait of Belle Isle Terranova - the "first Europeans to regularly visit North America"[79] focused on the harbor of Red Bay in the 16th century.[79][80] In the 16th century there was extensive trade contact overall friendly exchanges between the Basque whalers and the Mi'kmaq which provided the basis for the development of an Algonquian–Basque pidgin in the mid-16th century, with a strong Mi'kmaq imprint, recorded still in use in the early 18th century. Linguist P. Bakker identified two Basque loanwords in Mi'kmaq.[79][81][82] |

17th century

| Year | Date | Event |

|---|---|---|

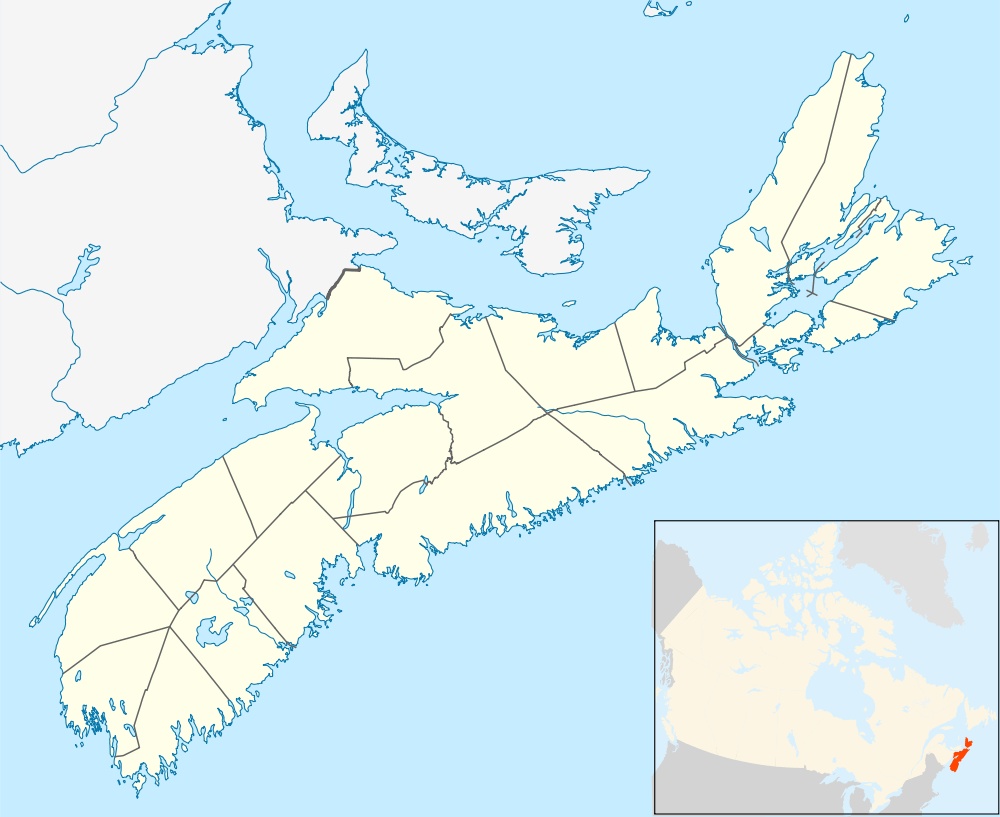

| 1603 | Samuel de Champlain first encountered the Mi'kmaq - whom he referred to the Souriquois after the Shediac River (Jedaick in the original Mi’kmaq which Champlain referred to as the Souricoua River) - on his first expedition to North America in 1603. He visited the traditional lands of the Mi'kmaq people in the Shediac area in southeast New Brunswick including Percé, Quebec Sigsôg ("steep rocks" or "crags") and Pelseg ("fishing place") which he named Isle Percée ("Pierced Island").[83][84] The Mi'kmaq had a large encampment - Gédaique - meaning "running far in." The Mi'kmaq used the copper from a mine in the area which is found in burial sites.[85] Champlain observed that the winter encampment of the Mi'kmaq was on Cape Breton Island. According to archaeological finds - including stone and copper tools - the Shediac watershed "appears to have been a transportation nexus" for "thousands of generations." The material culture of the "first ten thousand years" include "tools, adornments and weapons" made out of stone and copper by pre-contact people.[47] | |

| 1606 | 1607 | Marc Lescarbot - lawyer, traveler, and writer - stayed in Port-Royal from July 1606 until the spring of 1607. From there he went to the Saint John River and Île Sainte-Croix. He wrote about the first European encounters with the Mi'kmaq and the Malécite in his book Histoire de la Nouvelle-France published in 1609. Lescarbot made notes on native songs and languages.[86][87] "Lescarbot described hill planting and intercropping of corn and beans among the aboriginal peoples of Maine, Virginia and Florida."[88]:122 |

| 1608 | 1608-1760 "This alliance between French and First Nations forcing each into the others arms, created our first example of intercultural learning in Canadian history. Indians had helped scurvy-ridden men cure themselves with white cedar. Natives taught the French how to survive the winter. They supplied them with valuable geographical information. The French learned the value of birch bark canoes, toboggans, and snowshoes. They learned how to make maple sugar and collect berries."[89]:57 | |

| 1610 | Henri Membertou also known as Kjisaqmaw Maupeltuk, chief of the Mi'Kmaq, sakmow (Grand Chief) of the Mi'kmaq First Nations - entered into a relationship with the Catholic Church - the Mi'kmaq Concordat.[90] A lay priest - Jessé Fléché - baptized Sakmowk Membertou and twenty-one of his immediate family members was baptized by a lay priest Jessé Fléché on June 24, 1610. Sakmowk Membertou encouraged all of his people to convert.[91]:9[92]:10[93]:35:53 | |

| 1611 | Henri Membertou was the Grand Chief of the Grand Council made up of chiefs Keptinaq from the seven district councils in Mi'kma'ki, Elders, the Putús, the women's council, and the Grand Chief. He was at least one hundred years old when he died on 18 September 18, 1611. He was originally chief of the Kespukwitk district where the French first overwintered in Port Royal. | |

| 1669 | Pierre-Esprit Radisson in the English service, sailed along the coast from the Rupert River to the Nelson River both in Hudson Bay. | |

| 1670-1 | Pierre-Esprit Radisson explored the James Bay area in the winter of 1670/71 from the base at Rupert House. | |

| 1673 | Charles Bayly of the Hudson's Bay Company established a fur-trading post originally called Moose Fort at what is now Moose Factory. |

18th century

| Year | Date | Event |

|---|---|---|

| 1763 | Royal Proclamation of 1763 | |

| 1793 | Nuxálk and Carrier guides led Alexander MacKenzie along the grease trails to the Pacific Ocean when natural obstacles in the Fraser River prevented his continued water route. Nuxalk-Carrier Route or Blackwater Trail was part of a long used network of trails originally used by the Nuxálk and Carrier people for communication, transport and trade, in particular, trade in Eulachon grease from the Pacific coast. | |

| 1799 | Makenunatane "Swan Chief", was a visionary leader, who foresaw the changes coming that would affect his people, the Dunne-za or Beaver Nation. He believed his people should adopt the more individualistic life of the fur trapper-trader rather than continue with the communal hunts to survive. He led his people to a trading post to initiate contact with the traders. He also encouraged them to accept Christianity as he believed the Christian rituals were more appropriate to the life of fur traders and Christianity was a short cut to heaven. Swan Chief got his name because of his ability to fly like the swan. He had powerful visions of the bison hunt and organized the surround and slaughter hunts with skill because of his visions.;[94][1] |

19th century

| Year | Date | Event |

|---|---|---|

| 1812 | "British support for First Nations was a source of conflict that was the foundation for the Revolutionary War and continued with the War of 1812.[95] "During the War of 1812, an alliance was established and a respectful relationship grew between a British leader, Major General Isaac Brock, a British Officer, and an emerging Shawnee leader of the First Nations named Tecumseh."[96] After the war the traditional roles for Indian people in colonial society declined rapidly.[97] | |

| 1821 | A trading post was established at York Factory as headquarters of the Hudson's Bay Company's Northern Department. They traded with the Swampy Cree (Maškēkowak / nēhinawak). | |

| 1839 | Upper Canada passed a law to protect Indian reserves, basically including Indian lands in with crown lands.[97] | |

| 1840s | The first Indian residential schools in Canada were set up in the 1840s with the last residential school closing in 1996.[98] | |

| 1867 | The British North America Act of 1867Constitution Act, 1867 established Canada as a self-governing country. | |

| 1868 | The British Parliament passed the Rupert's Land Act 1868 – "An Act for enabling Her Majesty to accept a Surrender upon Terms of the Lands, Privileges and Rights of ‘The Governor and Company of Adventurers of England trading into Hudson’s Bay’ and for admitting the same into the Dominion of Canada." | |

| 1869-70 | On November 19, 1869, HBC surrendered its charter to the British Crown, which was authorized to accept the surrender by the Rupert's Land Act.

The new Canadian government compensated the Hudson's Bay Company £300,000 ($1.5 million)(£27 million in 2010)[99] for dissolving it HBC's charter with the British Crown. The HBC had exclusive commercial domain over Rupert's Land—a vast continental expanse—a third of what is now Canada.[100] By order-in-council dated June 23, 1870,[101] the British government admitted Rupert's Land to Canada through the Constitution Act, 1867,[102] effective July 15, 1870, conditional on the making of treaties with the sovereign indigenous nations providing consent to the Queen. | |

| 1871 | Treaty 1, a controversial agreement established August 3, 1871 between Queen Victoria and Brokenhead Ojibway Nation, Fort Alexander (Sagkeeng First Nation), Long Plain First Nation, Peguis First Nation, Roseau River Anishinabe First Nation, Sandy Bay First Nation and Swan Lake First Nation in South Eastern Manitoba including the Chippewa and Swampy Cree tribes, was the first of the numbered Treaties.[103] | |

| 1871 | "Your Great Mother, therefore, will lay aside for you 'lots' of land to be used by you and your children forever. She will not allow the white man to intrude upon these lots. She will make rules to keep them for you, so that as long as the sun shall shine, there shall be no Indian who has not a place that he can call his home, where he can go and pitch his camp or if he chooses build his house and till his land."[104] | |

| 1875 | In 1875 the Government of Canada had granted a 57.9 kilometres (36.0 mi) strip of land along the western shore of Lake Winnipeg between Boundary Creek and White Mud River inclusive of Hecla Island to Icelandic immigrants who established a settlement in what is now Gimli in the fall of 1875.[105][106] | |

| 1876 | A severe smallpox epidemic erupted in 1876 originating from the second wave of hundreds of Icelandic settlers[107] resulting in hundreds of deaths as it quickly spread to the indigenous First Nation population[106][108] including the nearby Sandy Bar Band first nation community at Riverton.[108][109][110][111] The newly formed Council of Keewatin imposed severe restrictions on the fur trade with furs and trading posts burnt to prevent the spread of smallpox and no possibility of compensation.[112] The epidemic and quarantine postponed the move until the summer of 1877 when 43 families—representing 200 people made the 200 mile journey south to the present day Fisher River Reserve. | |

| 1876 | The Indian Act, a Canadian statute that concerns registered Indians, their bands, and the system of Indian reserves was first passed in 1876 and is still in force with amendments, it is the primary document which governs how the Canadian state interacts with the 614 Indian bands in Canada and their members. Throughout its long history the act has been an ongoing source of controversy and has been interpreted in many ways by both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal Canadians. The legislation has been amended many times, including "over twenty major changes" made by 2002.[97][113] The provisions of Section 91(24) of the Constitution Act, 1867, provided Canada's federal government exclusive authority to legislate in relation to "Indians and Lands Reserved for Indians".[114] | |

| 1876 | 25 November | The District of Keewatin was created by the passage of the Keewatin Act on October 7, 1876[115] The government of Canada established the Council of Keewatin with Lieutenant Governor Alexander Morris as its head. The Council was disbanded on April 16, 1877. |

| 1877 | Following the signing of Treaty 5 the Fisher River Cree Nation a "surplus population" of 180 people who had been living at Norway House 200 miles south to Fisher River in 1877 and 1888.[116]:220 The HBC earned $1000 in revenue by assisting with the move.[116]:148:222 | |

| 1879 | This year is remembered by the Blackfoot Confederacy or Niitsitapi as Itsistsitsis/awenimiopi meaning when first/no more buffalo.[117]:96 | |

| 1883 | Sir Hector-Louis Langevin PC KCMG CB QC (August 25, 1826 – June 11, 1906), a Canadian lawyer, politician and one of the Fathers of Confederation played an important role in the establishment of the Canadian Indian residential school system. As Secretary of State for the Provinces, Langevin made it clear to Parliament in 1883 that day schools would be insufficient in assimilating Aboriginal children. Langevin was one of the architects of the residential schools and argued: “The fact is that if you wish to educate the children you must separate them from their parents during the time they are being taught. If you leave them in the family they may know how to read and write, but they will remain savages, whereas by separating them in the way proposed, they acquire the habits and tastes…of civilized people.”[118]:65 | |

| 1884 | The Great Marpole Midden, an ancient Musqueam village and burial site located in the Marpole neighbourhood of Vancouver, British Columbia, was uncovered during road upgrading. | |

| 1888 | St. Catherines Milling v. The Queen, regarding lands on Lake Wabigoon granted to a lumber company by the federal government, thought to be within Rupert's Land when Canada entered into Treaty 3 in 1873 with the Ojibway. It was the leading case on aboriginal title in Canada for more than 80 years. See R. v. Guerin. | |

| 1899 | Treaty 8 was the last formal treaty signed by a First Nation in British Columbia until Nisga agreement. |

20th century

| Year | Date | Event |

|---|---|---|

| 1900 | The Beaver peoples suffering from disease and starvation, were the last band to sign Treaty 8 in May, 1900. | |

| 1907 | In Moose Factory, Bishop Horden Memorial School also known as Horden Hall Residential School, Moose Factory Residential School, Moose Fort Indian Residential School (1907-1963), named after Bishop Horden, serving all the communities in the James Bay area, was run by the Anglican Church.[119] The Truth and Reconciliation Commission investigated the school which, like others across Canada, where the highest number of premature deaths among children at these schools was from tuberculosis.[120][121] | |

| 1922 | Peter Henderson Bryce self-published The Story of a National Crime: an Appeal for Justice [122] in which he expressed grave concerns about the Indian residential schools in Canada. His original 1907 report was a scathing indictment of the condition of the church-run schools. He noted the number of children who had died at the schools from tuberculosis. He argued that the over-crowded and over-heated facilities combined with lack of nutrition and hygiene created an environment where children became deathly ill. When Duncan Campbell Scott ignored his report and then fired him, he published this document. | |

| 1930 | By 1930 the caribou in the Newfoundland interior — upon which the Mi'kmaq depended — had been hunted to near extinction. With the completion of the railway across Newfoundland in 1898 large numbers of sports hunters and settlers had easy access to the huge interior boreal woodland caribou herds. This led to an appalling slaughter with the caribou populations dropping from "about 200,000-300,000 in 1900 to near extinction by 1930."[123] | |

| 1933 | The Great Marpole Midden, an ancient Musqueam village and burial site located was designated as a National Historic Site of Canada. | |

| 1940s | The First Nations nutrition experiments were conducted on isolated communities and residential school children. | |

| 1950s, 1960s | UBC professor Charles Edward Borden undertook salvage archaeology projects at Great Marpole Midden. Borden "was the first to draw links between contemporary Musqueam peoples and excavated remains." | |

| 1961 | In the early 1960s, the National Indian Council was created in 1961 to represent indigenous people of Canada, including treaty/status Indians, non-status Indians, the Métis people, though not the Inuit.[124] | |

| 1963 | In 1963, the federal government commissioned University of British Columbia anthropologist Harry B. Hawthorn to investigate the social conditions of Aboriginal peoples across Canada. The Hawthorn Reports of 1966 and 1967 "concluded that Aboriginal peoples were Canada’s most disadvantaged and marginalized population. They were "citizens minus." Hawthorn attributed this situation to years of failed government policy, particularly the residential school system, which left students unprepared for participation in the contemporary economy."[125][126][127] | |

| 1960s | The Sixties Scoop was coined by Patrick Johnston in his 1983 report Native Children and the Child Welfare System.[128][129] It refers to the Canadian practice, beginning in the 1960s and continuing until the late 1980s, of apprehending unusually high numbers of children of Aboriginal peoples in Canada and fostering or adopting them out, usually into white families.[130] | |

| 1965 | The Supreme Court upheld the treaty hunting rights of Indian people on Vancouver Island against provincial hunting regulations in R. v. White and Bob.[131] | |

| 1969 | Frank Arthur Calder and the Nisga'a Nation Tribal Council brought an action against the British Columbia government claimed they had legal title to their traditional territory.[132]AANDC They declared that aboriginal title to certain lands in the province had never been lawfully extinguished. | |

| 1969 | 1969 White Paper was a Canadian policy paper by Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau and his Minister of Indian Affairs, Jean Chrétien in 1969 proposing the abolition the Indian Act and dismantling of the established legal relationship between Aboriginal peoples and the state of Canada in favour of equality. The federal government proposed that, by eliminating "Indian" as a distinct legal status, equality among all Canadians would result. The White Paper proposed to [125] eliminate Indian status, dissolve the Department of Indian Affairs within five years, abolish the Indian Act, convert reserve land to private property that can be sold by the band or its members, transfer responsibility for Indian affairs from the federal government to the province and integrate these services into those provided to other Canadian citizens, provide funding for economic development and appoint a commissioner to address outstanding land claims and gradually terminate existing treaties The federal government at the time argued that the Indian Act was discriminatory and that the special legal relationship between Aboriginal peoples and the Canadian state should be dismantled in favour of equality, in accordance with Trudeau's vision of a "just society." The federal government proposed that by eliminating "Indian" as a distinct legal status, the resulting equality among all Canadians would help resolve the problems faced by Aboriginal peoples. | |

| 1971 | October | The Manitoba Indian Brotherhood - now the Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs - presented their landmark position paper entitled, "Wahbung: Our Tomorrows"—in opposition to then-Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau's 1969 White Paper which proposed the abolition of the Indian Act. After opposition from many Aboriginal leaders—including the MIB—the white paper was abandoned in 1970.[133][134][135] |

| 1973 | The Supreme Court of Canada in Calder v. British Columbia (Attorney General) 4 W.W.R. 1 was the first time that Canadian law acknowledged that aboriginal title to land existed prior to the colonization of the continent and was not merely derived from statutory law. | |

| 1973 | The Federation of Newfoundland Indians — which included Mi'kmaq from all across the island formed in order to achieve federal recognition.[123] | |

| 1982 | Section Thirty-five of the Constitution Act, 1982 provides constitutional protection to the aboriginal and treaty rights of Aboriginal peoples in Canada. | |

| 1984 | R. v. Guerin 2 S.C.R. 335 was a landmark Supreme Court of Canada decision on aboriginal rights where the Court first stated that the government has a fiduciary duty towards the First Nations of Canada and established aboriginal title to be a sui generis right. The Musqueam Indian band won their case. | |

| 1985 | Bill C-31. | |

| 1990 | June | In 1990, Elijah Harper, OM (1949 – 2013) a Canadian politician and Chief of his Red Sucker Lake, Manitoba, held an eagle feather as he refused to accept the Meech Lake Accord because it did not address any First Nations grievances.[136][137][138] Harper was the first "Treaty Indian" in Manitoba to be elected as a member of the Legislative Assembly of Manitoba. |

| 1990 | ... | The third, final constitutional conference on Aboriginal peoples was also unsuccessful. The Manitoba assembly was required to unanimously consent to a motion allowing it to hold a vote on the accord, because of a procedural rule. Twelve days before the ratification deadline for the Accord, Harper began a filibuster that prevented the assembly from ratifying the accord. Because Meech Lake failed in Manitoba, the proposed constitutional amendment failed.CITEREFCohen1990[138]CITEREFJ.C3.BCrgen2001 |

| 1991 | The Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples was a Canadian Royal Commission established in 1991 to address many issues of aboriginal status that had come to light with recent events such as the Oka Crisis and the Meech Lake Accord | |

| 1996 | The report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples was published setting out "a 20-year agenda for implementing changes."[139] | |

| 1996 | The 'Nisga'a Final Agreement or Nisga'a Treaty was signed by Joseph Gosnell, Nelson Leeson and Edmond Wright of the Nisg_a'a Nation. Nisga'a Treaty the long-standing and historic land claims made by the Nisg_a'a with the government of British Columbia, and the Government of Canada. As part of the settlement in the Nass River valley nearly 2,000 square kilometres of land was officially recognized as Nisg_a'a, and a 300,000 cubic decameter water reservation was also created. Bear Glacier Provincial Park was also created as a result of this agreement. Thirty-one Nisga'a placenames in the territory became official names.[140] The land-claim settlement was the first formal treaty signed by a First Nation in British Columbia since Treaty 8 in 1899. The agreement gives the Nisga'a control over their land, including the forestry and fishing resources contained in it. | |

| 1997 | Delgamuukw v. British Columbia 3 S.C.R. 1010, is a decision of the Supreme Court of Canada where the Court expressly and explicitly declined to make any definitive statement on the nature of aboriginal title in Canada. In 1984 the Gitksan and the Wet'suwet'en Nation claimed ownership of land in northwestern British Columbia. | |

| 1999 | Canadian Indigenous Languages and Literacy Development Institute (CILLDI) was established in 1999.[141] |

21st century

| Year | Date | Event |

|---|---|---|

| 2005 | During the visit of Queen Elizabeth II to Alberta and Saskatchewan in 2005, provincial and federal ministers denied First Nation leaders private audience with the monarch - something they have had since the 1600s.[142] Land claim disputes, as well as a perceived intervention of the Crown into aboriginal affairs threatened relationships between The Canadian Crown and Aboriginal peoples .[143] | |

| 2006 | In 2006, a court-approved Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement (IRSSA), the largest class action in Canada’s history was reached with implementation to begin in September 2007.[144]:1 Crawford Class Action was the court-appointed administrator. Various measures to address the legacy of Indian Residential Schools (IRS) included a $20 million Commemoration Fund for national and community commemorative projects, $1.9 billion for the Common Experience Payment (CEP), Independent Assessment Process (IAP), $60 million for the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) to document and preserve the experiences of survivors, Healing Support such as Resolution Health Support Worker (RHSW) Program and $125 million for the Aboriginal Healing Foundation (AHF). The IRSSA offered former students blanket compensation through the Common Experience Payment (CEP) which averaged lump-sum payment of $28,000. Payments were higher for more serious cases of abuse.[145][144]:1 The CEP, a component of the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement, "part of an overall holistic and comprehensive response to the Indian residential school legacy." The CEP recognized "the experience of living at an Indian Residential School(s) and its impacts. All former students who resided at a recognized Indian Residential School(s) and were alive on May 30, 2005 were eligible for the CEP. This include[d] First Nations, Métis, and Inuit former students."[146] "To benefit former students and families: $125 million to the Aboriginal Healing Foundation for healing programmes; $60 million for truth and reconciliation to document and preserve the experiences of survivors; and $20 million for national and community commemorative projects."[146] | |

| 2007 | 13 September | The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) was adopted by the General Assembly on Thursday, 13 September 2007, by a majority of 144 states in favour, 4 votes against (Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United States) and 11 abstentions (Azerbaijan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Burundi, Colombia, Georgia, Kenya, Nigeria, Russian Federation, Samoa and Ukraine).[147][148] |

| 2008 | 2 June | The Indian Residential Schools Truth and Reconciliation Commission, a truth and reconciliation commission was launched.[149] |

| 2008 | March | Indigenous leaders and church officials embarked on a multi-city "Remembering the Children" tour to promote the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.[150] |

| 2008 | October 20 | Justice Justice Harry LaForme, chair of the Indian Residential Schools Truth and Reconciliation Commission resigned, claiming "the commission was on the verge of paralysis and doomed to failure. He cited an "incurable problem" with the other two commissioners — Claudette Dumont-Smith and Jane Brewin Morley — whom he said refused to accept his authority as chairman and were disrespectful."[145] |

| 2009 | October 15 | The Indian Residential Schools Truth and Reconciliation Commission was relaunched by then-Governor General Michaëlle Jean with Justice Murray Sinclair, an Ojibway-Canadian judge, First Nations lawyer, was the chair.[151][145] |

| 2015 | June | The Indian Residential Schools Truth and Reconciliation Commission was completed in June 2015. It included 94 calls to action.[152] |

See also

- Aboriginal peoples in Canada

- First Nations

- Index of Aboriginal Canadian-related articles

- Settlement of the Americas [Notes 1]

Notes

- ↑ This well-documented article discusses conflicting theories on the pre-history of settlement.

Citations

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Dickason, McNab & 1992 3.

- ↑ Deloria, Vine (1995). Red Earth, White Lies: Native Americans and the Myth of Scientific Fact. Scribner. New York. ISBN 0-684-80700-9.

- ↑ Jenkins, Philip (November 24, 2005). Dream Catchers: How Mainstream America Discovered Native Spirituality. OUP USA. ISBN 978-0-19-518910-0.

- ↑ O'Leary, Denyse (August 3, 2004). By Design or by Chance in the Universe: The Growing Controversy on the Origins of Life. Augsburg Fortress. ISBN 978-0-8066-5177-4.

- ↑ Lorenz, Melissa (2008), "Vine Deloria Jr.", Minnesota State University, Mankato, EMuseum Archived copy retrieved April 19, 2015

- 1 2 Mikkel W. Pedersen, Anthony Ruter, Charles Schweger, Harvey Friebe, Richard A. Staff, Kristian K. Kjeldsen, Marie L. Z. Mendoza, Alwynne B. Beaudoin, Cynthia Zutter, Nicolaj K. Larsen, Ben A. Potter, Rasmus Nielsen, Rebecca A. Rainville, Ludovic Orlando, David J. Meltzer, Kurt H. Kjær, Eske Willerslev (August 10, 2016). Postglacial viability and colonization in North America’s ice-free corridor. Nature (Report). doi:10.1038/nature19085. Retrieved August 10, 2016.

- 1 2 3 Chung, Emily (August 10, 2016). "Popular theory on how humans populated North America can't be right, study shows: Ice-free corridor through Alberta, B.C. not usable by humans until after Clovis people arrived". CBC News. Retrieved August 10, 2016.

- ↑ McGhee 2012.

- ↑ Wilkerson, Corinne D. January 2010. Population Genetics of Woodland Caribou (Rangifer tarandus caribou) on the Island of Newfoundland Master of Science thesis. Department of Biology. Memorial University of Newfoundland.

- 1 2 Julig & Hurley 1987.

- ↑ Herz, Garrison & 1998 125.

- ↑ Reynolds & MacKinnon 1998-2002.

- 1 2 Day 2003.

- ↑ Shaw nd.

- ↑ Gibbon & Ames 1998.

- ↑ AlbertaJasper (n.d.), "Alberta History pre 1800 - Jasper Alberta", AlbertaJasper.com Reference details unavailable.

- ↑ CNRC nd.

- ↑ Cambridge 2007.

- ↑ Meltzer 2009.

- ↑ Tamm, Kivisild & Reidla 2007.

- ↑ A & 1987 333.

- ↑ Irving & 1987 8-13.

- ↑ VG 1998-2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Harris & 1987 plate 14.

- ↑ Ehlers & Gibbard 2004.

- ↑ Frison 2000.

- ↑ Meyer, Daniel A. and Jason Roe Excavations at the Upper Lovett Campsite, Alberta volume 49, number 2

- ↑ 1998 Manitoba Archaeological Society. Web Development: Brian Schwimmer, University of Manitoba. Text and Graphics: Brian Schwimmer, Virginia Petch, Linda Larcombe Folsom Traditions

- 1 2 3 4 Canadian Museum of Civilization 2010.

- ↑ Reynolds, MacKinnon & MacDonald 1998-2002.

- ↑ "Evolution of Projectile Points". U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management. Retrieved 2011-09-19.

- ↑ "Western Plano". Manitoba Archaeological Society. Retrieved 2011-09-19.

- ↑ Waldman, Carl (2009) [1985]. Atlas of the North American. New York: Facts on File. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-8160-6858-6.

- 1 2 Flasmark & 1996 11-20.

- ↑ Driver 2005.

- 1 2 Nenan 2009.

- ↑ Fladmark 1983.

- 1 2 Fladmark et al. 371-384.

- ↑ Heaton 1996.

- ↑ T8FNs & 2012 51.

- ↑ Dickason, McNab & 1992 55.

- ↑ CEAA 2013.

- ↑ Whitford & Stantec 2009.

- ↑ MacDonald, George (1968). Debert: A Palaeo-Indian Site in Central Nova Scotia. Ottawa: National Museum of Man. p. 3.

- ↑ "The Debert Palaeo-Indian National Historic Site". Canadian Museum of Civilization. Retrieved 15 April 2013.

- ↑ "Debert Palaeo-Indian Site". Retrieved 15 April 2013.

- 1 2 Leonard, Kevin (2002). Jedaick (Shediac, New Brunswick): a Nexus through Time for Shediac Bay Watershed Association (PDF) (Report). Retrieved August 8, 2016.

- ↑ Debert Palaeo-Indian Site. Canadian Register of Historic Places. Retrieved 30 September 2012.

- ↑ Meyer, Daniel A. and Jason Roe. 2007. Excavations at the Upper Lovett Campsite, Alberta volume 49, number 2

- ↑ Driver, Jonathan C. 1999 Raven skeletons from Paleoindian contexts, Charlie Lake Cave, British Columbia. American Antiquity 64(2):289-298.

- ↑ Driver JC, Handley M, Fladmark KR, Nelson DE, Sullivan GM, and Preston R. 1996. Stratigraphy, Radiocarbon Dating, and Culture History of Charlie Lake Cave, British Columbia. Arctic 49(3):265-277.

- ↑ Fladmark, Knut R., Jonathan C. Driver, and Diana Alexander 1988 The Paleoindian Component at Charlie Lake Cave (HbRf 39), British Columbia. American Antiquity 53(2):371-384.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Barnable, K. Stuart (June 2008), Archaeological Background (PDF), Archaeological Overview Assessment Proposed Airport Logistics Park, Prince George, Prince George, British Columbia: Ecofor Consulting, retrieved 10 November 2014

- ↑ Smith 1997.

- ↑ Parks Canada nd.

- ↑ Carlson 2001.

- ↑ Fladmark & 1986 50.

- ↑ Hutchinson Encyclopedia

- ↑ Collections Canada 2000.

- ↑ Gerry Oetelaar. "In the Beginning" (PDF). Parkdale Community Heritage Inventory. Calgary: 6–7. Retrieved 14 November 2011.

- ↑ (PSWG) Paskapoo Slopes Stakeholder Working Group (2009). "Paskapoo Slopes Natural Park". The Broadcaster (September). Retrieved 12 November 2011.

- ↑ Carlson 1996a.

- ↑ Reeves 1998, p. iii.

- ↑ "Ripley Ridge Retreat History". Ripley Ridge Retreat. Retrieved 18 November 2011.

- ↑ City of Calgary & 2005-2013 47.

- ↑ Spurling & Ball 1981.

- ↑ Elaine Anton.2004.

- ↑ UBC Museum of Anthropology nd, p. 9.

- 1 2 Andrews, Tom (26 April 2010), Ancient artifacts revealed as northern ice patches melt: Scientists hope to save artifacts as ice recedes, Yellowknife, NT: Arctic Institute of North America

- ↑ "History – Aboriginal Sites". L'Anse aux Meadows National Historic Site of Canada. Parks Canada. Retrieved 2008-01-20.

- ↑ Chisholm & Gutsche 1998, p. 178.

- 1 2 Chisholm & Gutsche 1998, p. 136-7.

- ↑ Chisholm & Gutsche 1998, p. 132.

- ↑ Warrick, Gary A. (1990), A Population History of the Huron-Petun, A.D. 500-1650 (PhD Thesis), Montreal, PQ: McGill University

- ↑ Warrick, Gary A. (2008), A Population History of the Huron-Petun, A.D. 500-1650, New York: Cambridge University Press via Google Books

- ↑ Archeological Services, Inc., Mantle Site; see also the entries for the Aurora (Old Fort) and Ratcliff Wendat ancestral village sites in Whitchurch-Stouffville.

- ↑ James F. Pendergast, "The Confusing Identities Attributed to Stadacona and Hochelaga", Journal of Canadian Studies, Winter 1998, pp. 3–4, accessed Feb 3, 2010.

- ↑ Burgar & Crinnion 2005.

- 1 2 3 Bakker, Peter (April 1989). "Two Basque Loanwords in Micmac". International Journal of American Linguistics. 55 (2): 258–261. doi:10.1086/466118.

- ↑ Barkham, S. H. (1984). "The Basque Whaling Establishments in Labrador 1536-1632 - A Summary". Arctic. 37: 515–519. doi:10.14430/arctic2232.

- ↑ Bakker, Peter (2013). "Amerindian tribal names in North America of possible Basque origin". OJS. Retrieved August 8, 2016.

- ↑ Whitehead, R. H. (1993), "Nova Scotia: the Protohistoric Period, 1500-1630", Department of Education, Nova Scotia Museum Complex, Halifax

- ↑ Champlain, Samuel de. Champlain's Voyage in 1603. Gutenberg (Report). II."La rivière de Gédaïc, ou Chédiac. On l'appelait alors Souricoua, sans doute parce que c'était le chemin des Souriquois."

- ↑ "Percé (ville)" (in French). Commission de toponymie du Québec. Retrieved 2011-12-07.

- ↑ Rand, Silas Tertius (1875-01-01). A First Reading Book in the Micmac Language: Comprising the Micmac Numerals, and the Names of the Different Kinds of Beasts, Birds, Fishes, Trees, &c. of the Maritime Provinces of Canada. Also, Some of the Indian Names of Places, and Many Familiar Words and Phrases, Translated Literally Into English. Nova Scotia Printing Company.

- ↑ Lescarbot, Marc (1617). Histoire de la Nouvelle-France [History of New France - Third Edition] (in French) (Troisième Edition enrichie de plusieurs choses singulieres, outre la suite de l'Histoire ed.).

- ↑ Lescarbot, Marc (2007-08-08). Histoire de la Nouvelle-France [History of New France - Third Edition] (E-Book) (in French) (Troisième Edition enrichie de plusieurs choses singulieres, outre la suite de l'Histoire ed.). Project Gutenberg Ebook #22268. Retrieved 2010-10-08.

- ↑ Cornelius, Carol (1999). Iroquois Corn in a Culture-Based Curriculum: A Framework for Respectfully. SUNY Press. p. 269. ISBN 0791499839.

- ↑ Welton, M. R. (2010). "A country at the end of the world: Living and learning in New France, 1608-1760". The Canadian Journal for the Study of Adult Education. 23 (1): 55–71.

- ↑ Henderson, James (Sákéj) Youngblood (1997). The Míkmaw Concordat. Halifax, Nova Scotia: Fernwood. ISBN 1895686806.

- ↑ Augustine, Stephen J. (September 9, 1998). A Culturally Relevant Education for Aboriginal Youth: Is there room for a middle ground, accommodating Traditional Knowledge and Mainstream Education? (PDF) (Masters of Arts, School of Canadian Studies thesis). Ottawa, Ontario: Carleton University. p. 96. Retrieved August 8, 2016. Citing Wallis and Wallis

- ↑ Wallis, Wilson D.; Wallis, Ruth Sawtell (1955), The Micmac Indians of Eastern Canada, Minneapolis: University of Minneapolis Press

- ↑ Prins, Harald E. L. (January 2, 1996). Spindler, George; Spindler, Louise, eds. The Mi'kmaq: Resistance, Accommodation, and Cultural Survival. Case Studies in Cultural Anthropology (1 ed.). Fort Worth: Earcourt Brace and Company. ISBN 0030534275.

- ↑ Ridington 1979.

- ↑ Goodman, W. H. (1941). The origins of the war of 1812: A survey of changing interpretations. The Mississippi Valley Historical Review, 28(2), 171-186.

- ↑ Aquash, Mark (2013). "First Nations in Canada: Decolonization and Self-Determination". in education. 19 (2). Retrieved July 15, 2016.

- 1 2 3 Leslie, John F. (2002), "The Indian Act: An Historical Perspective", Canadian Parliamentary Review, 25 (2), retrieved 12 September 2014

- ↑ Residential Schools Assembly of First Nations.

- ↑ http://safalra.com/other/historical-uk-inflation-price-conversion/

- ↑ "In Pursuit of Adventure: The Fur Trade in Canada and the NWC", McGill University Digital Library, nd, retrieved July 15, 2016

- ↑ Rupert's Land and North-Western Territory Order Archived 20 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Constitution Act, 1867 s. 146". Justice Laws Website. Department of Justice. 18 October 2015.

- ↑ "Numbered Treaty Overview". Canadiana.org (Formerly Canadian Institute for Historical Microreproductions). Canada in the Making. Retrieved 2009-11-16.

ARTICLES OF A TREATY made and concluded this third day of August in the year of Our Lord one thousand eight hundred and seventy-one, between Her Most Gracious Majesty the Queen of Great Britain and Ireland by Her Commissioner, Wemyss M. Simpson, Esquire, of the one part, and the Chippewa and Swampy Cree Tribes of Indians, inhabitants of the country within the limits hereinafter defined and described, by their Chiefs chosen and named as hereinafter mentioned, of the other part.

- ↑ Morris 1880.

- ↑ "Gimli History". Town of Gimli. Retrieved 2008-10-09.

- 1 2 Sommerville, S. J. (2002–2009). "MHS Transactions: Early Icelandic Settlement in Canada". Early Icelandic Settlement in Canada. Manitoba Historical Society MHS Transactions Series 3, 1944–45 season. Retrieved 2009-01-06.

- ↑ "The Atlas of Canada – Territorial Evolution, 1876". Natural Resources Canada. Government of Canada. 2004-01-28. Retrieved 2008-12-27.

- 1 2 "The Small-Pox". Vol III No. 121. Manitoba Daily Free Press. November 25, 1876. p. 3.

- ↑ "Unit 3 Aboriginal History on Hecla Island" (PDF). Heclas Island School Teacher's Guide.

- ↑ Lux, Maureen Katherine (2001). Medicine that Walks: Disease, Medicine, and Canadian Plains Native People, 1880–1940 (Digitized online by Google books). p. 139. ISBN 978-0-8020-8295-4. Retrieved 2008-12-28.

- ↑ Friesen, Gerald (1987). The Canadian Prairies: A History (Digitized online by Google books). University of Toronto Press. p. 139. ISBN 978-0-8020-6648-0. Retrieved 2008-12-28.

- ↑ "The Quarantine". Vol V No. 32 Whole No. 240. Manitoba Free Press. June 30, 1877. p. 3.

- ↑ Clegg 1982.

- ↑ Constitution Act

- ↑ Nicholson, Normal L. (1979). The Boundaries of the Canadian Confederation. Toronto: Macmillan Company of Canada Ltd. p. 113.

- 1 2 Tough, Frank (1997). As Their Natural Resources Fail: Native Peoples and the Economic History of Northern Manitoba, 1870-1930 (Digitized online by Google books). UBC Press. p. 392. ISBN 978-0-7748-0571-1. Retrieved July 14, 2016.

- ↑ Wonders, William C. (1 April 1983). "Far Corner Of The Strange Empire Central Alberta On The Eve Of Homestead Settlement". Great Plains Quarterly. Retrieved 8 November 2015.

- ↑ Grant 1996.

- ↑ Logotheti 1991, p. 17.

- ↑ Curry & Friesen 2008.

- ↑ Curry & Howlett 2007.

- ↑ Bryce, Peter Henderson. 1922. The Story of a National Crime: an Appeal for Justice

- 1 2 Pastore, Ralph T. (1998), "The History of the Newfoundland Mi'kmaq", Archaeology Unit & History Department, Memorial University of Newfoundland, retrieved July 15, 2016

- ↑ Assembly of First Nations Assembly of First Nations – The Story

- 1 2 First Nations Studies Program 2009 White Paper

- ↑ Hawthorn, Harry B. October 1966. A Survey of the Contemporary Indians of Canada: Economic, Political, Educational Needs and Policies The Hawthorn Report. Part 1

- ↑ Hawthorn, Harry B. October 1966. A Survey of the Contemporary Indians of Canada: Economic, Political, Educational Needs and Policies The Hawthorn Report. Part 2

- ↑ Johnston, Patrick (1983). Native Children and the Child Welfare System. Publisher: Canadian Council on Social Development. Ottawa, Ontario

- ↑ CBC Radio (March 12, 1983) "Stolen generations" Program: Our Native Land. Broadcast Date: March 12, 1983.

- ↑ Lyons, T. (2000). "Stolen Nation," in Eye Weekly, January 13, 2000. Toronto Star Newspapers Limited.

- ↑ INAC 1996.

- ↑ INAC 2007.

- ↑ Wahbung: Our Tomorrows, October 1971

- ↑ Kirkness, Verna (2008), "Wahbung: Our Tomorrows – 37 Years Later", UBC Open Library, Vancouver, BC, retrieved July 13, 2016

- ↑ Courchene (Nh Gaani Aki mini—Leading Earth Man), Dave (October 1971), "Wahbung: The Position Paper: a return to the Beginning for our Tomorrows: An Elder's Perspective" (PDF), Anishnabe Nation, Eagle Clan Sagkeeng First Nation, p. 8, retrieved July 13, 2016

- ↑ Jürgen 2001.

- ↑ Lambert 2013.

- 1 2 Parkinson 2006.

- ↑ INAC 1996a.

- ↑ BC nd.

- ↑ Rice, Sally; Thunder, Dorothy (May 30, 2016). Towards A Living Digital Archive of Canadian Indigenous Languages (PDF). Conference of the Canadian Association of Applied Linguistics (CAAL). Indigenous Languages and Reconciliation. Calgary, Alberta. Retrieved July 11, 2016. Held during the 2016 Congress of the Humanities and Social Sciences

- ↑ Monchuk, Judy (11 May 2005), "Natives decry 'token' presence for Queen's visit", The Globe and Mail, retrieved 14 February 2006

- ↑ Jamieson, Roberta (21 March 2003), Presentation to the Canadian House of Commons Standing Committee on Aboriginal Affairs, Northern Development and Natural Resources (PDF), archived from the original (PDF) on 28 September 2007, retrieved 26 November 2007

- 1 2 "Personal Credits for Personal or Group Education Services" (PDF), Assembly of First Nations, 2014, retrieved 4 June 2015

- 1 2 3 CBC 2009.

- 1 2 Residential School Settlement 2006.

- ↑ "Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples". United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues. Retrieved 11 December 2015.

- ↑ Coates, Ken (18 September 2013), Ken Coates; Terry Mitchell, eds., From aspiration to inspiration: UNDRIP finding deep traction in Indigenous communities, The Rise of the Fourth World, The Centre for International Governance Innovation (CIGI), retrieved 20 September 2013

- ↑ Residential School Settlement

- ↑ CBC 2008.

- ↑ University of Winnipeg nd.

- ↑ "Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to Action" (PDF), Truth and Reconciliation Commission, Winnipeg, Manitoba, p. 11

References

- BC (n.d.), Map of Nisga'a Lands and Treaty Placenames, Government of British Columbia

- Burgar, Bob; Crinnion, Cathy (June 2005), "The 'dirt' on the TRCA's archaeology program" (PDF), Arch Notes, Ontario Archaeological Society, 10 (3): 15, ISSN 0048-1742, retrieved 10 November 2014

- A History of Native People of Canada: Plano Culture, Canadian Museum of Civilization, 2010, retrieved 2011-09-19

- Carlson, Keith Thor (2001), A Stó:lo-Coast Salish Historical Atlas, Vancouver, BC: Douglas & McIntyre, pp. 6–18, ISBN 1-55054-812-3

- Carlson, R.L.; Dalla Bona, L., eds. (1996). The prehistory of Charlie Lake Cave. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press. pp. 11–20.

- Carlson, A. K. (1995), Archaeological Sites of the Nechako Canyon, Cheslatta Falls and Vicinity, Central Interior British Columbia. Traces Archaeological Research and Consulting. Report prepared for the Ministry of Forests, Vanderhoof District. Archaeological Permit 1994-097

- Carlson, A. K. (1996a), An Archaeological Potential Model for the Vanderhoof Forest District, B.C. Report prepared for the Ministry of Forests, Vanderhoof District by Traces Archaeological Research and Consulting, Ltd.

- Indian, church leaders launch multi-city tour to highlight commission, CBC, 2 March 2008, retrieved 4 June 2011

- "GG relaunches Truth and Reconciliation Commission", CBC, 15 October 2015, retrieved 4 June 2015

- "Sisson Project: Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) Report" (PDF), CEAA, July 2013, retrieved 10 November 2014

- Chisholm, B.; Gutsche, A (1998), Superior: Under the Shadow of the Gods, Toronto: Lynx Images, ISBN 0-9698427-7-5

- City of Calgary (13 June 2005), East Paskapoo Slopes Area Structure Plan (Aspen Village) (PDF), City of Calgary Land Use Mobility Planning and Transportation Policy, retrieved 2011-11-12

- CMM (12 May 2006), "Civilization.ca-Gateway to Aboriginal Heritage-Culture", Canadian Museum of Civilization Corporation, Government of Canada, archived from the original on 20 October 2009, retrieved 18 September 2009

- "Archaeology : Historical Overview: The Middle Prehistoric Period", Collections Canada, 31 August 2000, retrieved 9 November 2014

|chapter=ignored (help) - Cohen, Andrew (1990). A Deal Undone: The Making and Breaking of the Meech Lake Accord. Vancouver/Toronto: Douglas & McIntyre. ISBN 0-88894-704-6.

- CNRC (n.d.), Pre-glaciology in Alberta (PDF), National Research Council Canada, archived from the original (PDF) on March 22, 2004

- Day, Alan (2003), "The Topper Site in South Carolina", Ohio Archaeological Inventor, Cambridge, Ohio, retrieved 12 September 2013

- Driver, Jon (2005), Journey to a new land, Vancouver, BC: Simon Fraser University Museum

- Dickason, Olive P.; McNab, David T. (1992), A History of Founding Peoples from Earliest Times, Oxford University Press

- Ehlers, J.; Gibbard, P.L. (2004), Quaternary Glaciations: Extent and Chronology 2: Part II North America, Amsterdam: Elsevier, ISBN 0-444-51462-7

- Fladmark, Knut R. (1986). British Columbia Prehistory. Ottawa.

- Fladmark, Knut R.; Driver, Jonathan C.; Alexander, Diana (1988). "The Palaeoindian component at Charlie Lake Cave (HbRf 39), British Columbia". American Antiquity. 53 (2): 371–384. doi:10.2307/281025.

- Fladmark, Knut R. (1996), Carlson, R.L.; Dalla Bona, L., eds., The prehistory of Charlie Lake Cave, Early Human Occupation in British Columbia, Vancouver, BC: University of British Columbia Press, pp. 11–20

- Frison, George C. (August 2000), Prehistoric Human and Bison Relationships on the Plains of North America, Edmonton, Alberta: International Bison Conference

- Gibbon, Guy E; Ames, Kenneth M. (1998), Archaeology of Prehistoric Native America: An Encyclopedia, ISBN 978-0-8153-0725-9

- Grant, Agnes (1996), No End of Grief: Indian Residential Schools in Canada, Winnipeg: Pemmican

- Heaton, Timothy H. (February 1996), Cave fossils of Prince of Wales Island, Alaska Archipelago See also Northwest Coast Researchers List (Sitka)

- Julig, Patrick; Hurley, William (1987), William N. Irving (1927-1987) (PDF), Toronto, Ontario: Arctic Institute of North America (AINA)

- Harris, R. Cole (1 September 1987). R. Cole Harris, ed. Historical Atlas of Canada: I: From the Beginning to 1800. ISBN 0802024955.

- Herz, Norman; Garrison, Ervan G. (1998). Geological methods for archaeology. Oxford University Press. p. 125. ISBN 978-0-19-509024-6. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- INAC (1996), RCAP: The Role of the Courts, Ottawa, Canada: Indian and Northern Affairs, retrieved 17 September 2013

- INAC (1996a), Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples (RCAP), Ottawa, Canada: Indian and Northern Affairs, retrieved 17 September 2013

- INAC (2007), "The Role of the Courts", Statement of the Government of Canada on Indian Policy, Ottawa, Canada: Indian and Northern Affairs, retrieved 17 September 2013

- Irving, William N. (1987). "New Dates from Old Bones: Twisted Fractures in Mammoth Bones and Some Flaked Bone Tools Suggest that Humans Occupied the Yukon more than 40,000 Years Ago". Natural History. 96 (2).

- Rose Jürgen, JürgenJohannes Ch Traut, George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies (2001). Federalism and: perspectives for the transformation process in Eastern and Central Europe Volume 2 of George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies (digitised online by Google books). LIT Verlag Berlin-Hamburg-Münster. p. 151. ISBN 9783825851569.

- Lambert, Steve (20 May 2013). "Hundreds pay respects to Elijah Harper". Winnipeg, Manitoba: The Globe and Mail. Canadian Press. Retrieved 12 September 2014.

- MacDonald, Kerri (9 January 2009), "Chartering the right to healthcare: Weeneebayko Program has provided medical services for Moose Factory region since 1960s", The Journal, Kingston, Ontario: Queen's University, 136 (24), retrieved 3 January 2014

- McGhee, Robert (2012), Prehistory, The Canadian Encyclopedia

- Meltzer, David J. (2009). First Americans. Archived from the original on 1 November 2009. Retrieved 10 September 2013. David J. Meltzer, B.A., M.A., Ph.D., Southern Methodist University.

- Alexander Morris (1880), The Treaties of Canada with the Indians of Manitoba and the North-west Territories, including the Negotiations on which they were based, and other information relating thereto, Gutenberg

- Nenan (2009), People telling their story (PDF), Victoria, BC: The International Institute for Child Rights and Development (IICRD) Nenan Dane_Zaa Deh Zona Children & Family Services (Nenan)

- Parkinson, Rhonda (November 2006). "The Meech Lake Accord". Maple Leaf Web. Department of Political Science, University of Lethbridge. Retrieved 2009-09-11.

- "Banff National Park", Parks Canada, n.d., retrieved 9 November 2014

- Reeves, Brian.O.K. (1998). Historical Resources Inventory and Assessment, East Paskapoo Slopes (Permit 98-038). Consultants Report. Lifeways of Canada. Prepared for the City of Calgary. (Report). Edmonton, Alberta: Archaeological Survey of Alberta.

- "The Indian residential schools settlement has been approved" (PDF), Residential School Settlement

- Reynolds, Graham; MacKinnon, Richard; MacDonald, Ken (1998–2002), Palaeo-Indian archaeology: The Peopling of Atlantic Canada, Nova Scotia, Canada: Canadian Studies Program, Canadian Heritage, Cape Breton University With Folkus Atlantic Productions in Sydney. Supported by the Canadian Studies Program, Canadian Heritage, retrieved 19 December 2013

- Reynolds, Graham; MacKinnon, Richard (1998–2002), Palaeo-Indian archaeology, Nova Scotia, Canada The website was part of the "The Peopling of Canada" project supported by the Canadian Studies Program at Canadian Heritage. They also produced a CD ROM under another Canadian Studies Program project with the title: "The Peopling of Atlantic Canada".

- Ridington, Robin (1979). Changes of Mind: Dunne-za Resistance to Empire. Vancouver, BC: UBC Press. ISSN 0005-2949. Retrieved 17 September 2013.

- Shaw (n.d.). "Journey of mankind". Brad Shaw Foundation.

- Smith, Bruce (9 May 1997), "The Initial Domestication of Cucurbita Pepo in the Americas 10,000 years ago", Science, 276 (5314), pp. 932–934, doi:10.1126/science.276.5314.932

- Spurling, BE; Ball, BF (1981), "On some Distributions of the Oxbow 'Complex'", Canadian Journal of Archaeology, Canadian Archaeological Association

- Tamm, Erika; Kivisild, Toomas; Reidla, Maere (5 September 2007). "Beringian Standstill and Spread of Native American Founders". PLoS ONE. National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCIB). 2 (9). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0000829. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 1952074

. PMID 17786201.

. PMID 17786201. - T8FNs (27 November 2012). Telling a Story of Change the Dane-zaa Way: A Baseline Community Profile of Doig River First Nation, Halfway River First Nation, Prophet River First Nation and West Moberly First Nations (PDF) (Report). Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency (CEAA), Government of Canada. Retrieved 17 September 2013. authored by Treaty 8 First Nations (T8FNs) Community Assessment Team and the Firelight Group Research Cooperative.

- "Salish Weaving: an Art Nearly Lost", Musqueam Weavers Source Book (PDF), UBC Museum of Anthropology, n.d., retrieved 10 November 2014

- "Justice Murray Sinclair", University of Winnipeg, nd, retrieved 4 June 2015

- VG (1998–2009). "Life in Crow Flats-Part 1". Vuntut Gwitchin First Nation official website. Vuntut Gwitchin First Nation. Retrieved 6 September 2013.

Further reading

- Dickason, Olive P.; McNab, David T. McNab (1992), A History of Founding Peoples from Earliest Times, Oxford University Press

- Canada's First Nations:A History of Founding Peoples from Earliest Times. University of Oklahoma Press. 1992.

- CMM (May 12, 2006). "Civilization.ca-Gateway to Aboriginal Heritage-Culture". Canadian Museum of Civilization Corporation. Government of Canada. Archived from the original on 20 October 2009. Retrieved September 18, 2009.

- Andrews, Thomas D.; MacKay, Glen; Andrew, Leon (2009). Hunters of the Alpine Ice: The NWT Ice Patch Study. Yellowknife, NWT: Prince of Wales Northern Heritage Centre.

- Leslie, John F. (2002). "The Indian Act: An Historical Perspective". Canadian Parliamentary Review. 25 (2).

- Reynolds, Graham; MacKinnon, Richard (1998–2002), Palaeo-Indian archaeology, Nova Scotia, Canada