Typhoon Irma (1985)

| Typhoon (JMA scale) | |

|---|---|

| Category 2 (Saffir–Simpson scale) | |

Typhoon Irma on June 28 | |

| Formed | June 23, 1985 |

| Dissipated | July 1, 1985 |

| Highest winds |

10-minute sustained: 150 km/h (90 mph) 1-minute sustained: 165 km/h (105 mph) |

| Lowest pressure | 955 hPa (mbar); 28.2 inHg |

| Fatalities | 49 dead, 5 missing |

| Damage | $80 million (1985 USD) |

| Areas affected | Philippines, Japan |

| Part of the 1985 Pacific typhoon season | |

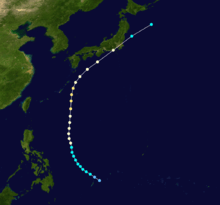

Typhoon Irma, known in the Philippines as Typhoon Dalin, affected the Philippines in late June 1985. Typhoon Irma originated from a monsoon trough situated along the western Pacific Ocean. It slowly developed, but lack of organization delayed classification as a tropical cyclone. By June 24, organization improved as the system encountered favorable conditions aloft. The next day, the disturbance attained tropical storm intensity. Moving west-northwest Irma gradually deepened, before weakening slightly on June 26. Thereafter, Irma slowed down, only to turn northward. On the morning of June 27, Irma was upgraded into a typhoon. After passing northeast of the Philippines, Irma attained peak intensity on June 29. Accelerating to the northeast, Irma steadily weakened as it encountered significantly less favorable conditions. The typhoon made landfall in central Japan on June 30. The system weakened below typhoon intensity the next day, and later on July 1, Irma transition into an extratropical cyclone. The remnants of the cyclone were tracked until July 7, when it merged with an extratropical low south of the Kamchatka Peninsula.

Meteorological history

During mid-June, the monsoon trough in the West Pacific extended eastward. At 0000 UTC on June 17, a disturbance was detected about 400 km (250 mi) southwest of the. Initially, the disturbance had a poorly defined surface circulation. Southwest of Typhoon Hal, the low was slow to develop. At this time, the disturbance was located south of a ridge, which was the main synoptic feature in the basin. An upper-level low (ULL) to the southeast of Guam associated with the tropical upper-tropospheric trough (TUTT) enhanced development. As such, the JTWC noted a fair chance of development. Moving west-northwest, the disturbance passed 180 km (110 mi) south-southeast of the Truk Atoll. Consequently, convection increased and become more organized. At midday, the JTWC issued a Tropical Cyclone Formation Alert.[1]

During the next three days, the disturbance remained poorly organized, even though the convection was intense. Data from a Hurricane Hunter aircraft on June 19 failed to locate a surface circulation. That afternoon, the TCFA was re-issued. On the afternoon, on June 20, the Hurricane Hunters founded a circulation and also observed falling pressures. The next day, the TCFA was re-issued again. Early on June 22, thunderstorm activity decreased due to the system's close proximity to Hal. Later that morning, the TCFA was cancelled. By June 24, vertical wind shear had diminished.[1] Several hours later, the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA) classified the cyclone as thunderstorm activity increased over the center.[2][nb 1] During the evening of June 24, the TCFA was re-issued for the fifth and final time. Thereafter, the cyclone became significantly better organized. At 0000 UTC on June 25, Dvorak analysis supported that the disturbance had attained tropical storm intensity. Less than two hours later, the JTWC upgraded the system to tropical storm intensity[1] while the Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration started to follow the storm and assigned it with the local name Daling.[4] At 0600 UTC, the JMA followed suit. At midday, the JMA upgraded Irma to severe tropical storm intensity,[2] four hours before a Hurricane Hunter aircraft measured winds of 50 mph (80 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 994 mbar (29.4 inHg). The aircraft also noted that the storm's strongest winds were 150 km (95 mi) displaced to the west of the center.[1]

Initially, Tropical storm Irma was expected by the JTWC to take a similar track to Hal along the monsoon trough into the South China Sea before curving around a subtropical ridge.[1] Irma slowly deepened, and according to the JMA, the system attained a secondary peak intensity of 70 mph (115 km/h).[2][nb 2] However, by June 26, the agency revised its forecast and showed Irma to not enter the South China Sea and instead take a more northerly trek. On June 27, Irma's forward speed slowed as it approached the edge of the ridge along the 130th meridian east[1] while intensifying.[2] That morning, both the JTWC and the JMA estimated that Irma attained typhoon intensity[6] based on data from ship reports.[1] Continuing to intensify, Irma moved northward.[6] However, by June 28, the JMA reported that Irma leveled off in intensity.[2] At 0000 UTC on June 29, the JTWC estimated a peak intensity of 105 mph (170 km/h) and a peak barometric pressure of 957 mbar (28.3 inHg).[6] Six hours later, the JMA increased the intensity of the typhoon to 90 mph (145 km/h), its maximum intensity. At this time, the agency also assessed the pressure of the storm at 960 mbar (28 inHg).[2]

Shortly after its peak, Typhoon Irma accelerated towards the northeast in the direction of central Japan under the influence of a mid-latitude cyclone.[1] Irma quickly weakened, and on the evening of June 29, the JMA decreased the intensity of Irma to 75 mph (120 km/h).[2] Meanwhile, Irma began to acquire extratropical characteristics. A Hurricane Hunter flight on June 30 suggested that that typhoon was encountering cooler and drier air, although the storm maintained a 55 km (35 mi) eye. That evening, the typhoon made landfall on Honshu.[1] At 0000 UTC on July 1, the JMA downgraded Irma into a severe tropical storm.[2] Six hours later, the cyclone completed its extratropical transition; the JTWC issued its final warning on the system.[1] The JMA continued the monitor the system as it passed northeast of the Kuril Islands. On July 7, the JMA ceased watching the system as it had merged with an extratropical low south of the Kamchatka Peninsula.[2]

Preparations and impact

Prior to the arrival of Irma, storm signals were issued for much of Luzon, including Samar and Catanduanes.[7] Even though Typhoon Irma passed well east to the Philippines, over 710 mm (30 in) of rain fell over parts of Luzon. These rains resulted in major flooding; Irma was also the second storm to directly affect the nation within a week, following Typhoon Hal.[1]

The capital of Manila sustained flooding along low-lying areas, which stranded motorists.[8] A total of 60% of the city was flooded, forcing the evacuation of 40,000 persons.[9] Six drownings occurred in the suburb of Quezon City, where 1,000 families were evacuated, 700 to churches and 300 to schools. Within the Manila metropolitan area, a man and a woman were also electrocuted. All classes in Manila were suspended, and many stores and offices shut down for a day because many employees could not attend work. Furthermore, domestic flights in and out of Manila were canceled since the runway was flooded with water 600 mm (25 in) deep. City-wide, eight people were killed; Irma was to worst tropical cyclone to directly impact Manila in over 10 years.[10]

Offshore Bataan, eight fisherman were initially rendered missing after a boat capsized.[10] In Olongapo City, seven people were buried due to a landslide.[9] In the downtown Santa Cruz area, all forms of transportation except for the railroad were immobile.[10] The Makati area sustained waist-deep flooding. Due to both Irma and Hal, 14 communities in Tarlac were flooded, leaving 375,000 displaced,[11] 116,963 of which were evacuated to 46 evacuation centers. Seven bridges were also damaged.[12] Overall, 46 people were killed due to Irma in the Philippines.[1]

Although the system remained offshore Taiwan,[1] it came close enough to require storm signals.[13] Upon making landfall on Honshu,[1] Irma became the first tropical system to strike the nation in 1985. Impacting an area already devastated by prior flooding,[14] A total of 1,475 mudslides occurred along Japan, resulting in 625 damaged homes.[12] Nearly 1,800 houses were flooded. Moreover, 650,000 customers were left without power at the height of the storm.[15] A total of 160 trains were delayed or cancelled, leaving 50,000 stranded. In Chiba Prefecture, one person was listed missing due to a drowning,[14] where seven persons were also hurt and over 200 houses were flooded.[16] Across Chiba, 400,000 were stranded.[15][17] In Tokyo, 119 trees were toppled and roads were flooded in 25 places.[14] Twenty domestic airline flights were cancelled and 26 railway lines within Toyko were suspended,[16] leaving 240,000 stranded.[15] Throughout the city, at least 40 dwellings sustained flooding.[16] In Izu Ōshima, 17 boats were swept away and 20 houses were damaged. Offshore, 26 individuals were rescued from a 5,100 ton freighter Gloria Fortuna.[14] In all, 493 people sought refuge in shelter. Eighty-nine houses were partially or full destroyed.[18] Thirty others were injured nationwide[14] and three people were killed, with five other missing.[1] Damage across the Philippines and Japan totalled US$80 million (1985 dollars).[19]

See also

- List of tropical cyclones

- Typhoon Hal (1985) – affected the Philippines right before

Notes

- ↑ The Japan Meteorological Agency is the official Regional Specialized Meteorological Center for the western Pacific Ocean.[3]

- ↑ Wind estimates from the JMA and most other basins throughout the world are sustained over 10 minutes, while estimates from the United States-based Joint Typhoon Warning Center are sustained over 1 minute. 10 minute winds are about 1.14 times the amount of 1 minute winds.[5]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Joint Typhoon Warning Center; Naval Pacific Meteorology and Oceanography Center (1986). Annual Tropical Cyclone Report: 1985 (PDF) (Report). United States Navy, United States Air Force. Retrieved August 11, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Japan Meteorological Agency (October 10, 1992). RSMC Best Track Data – 1980–1989 (.TXT) (Report). Retrieved August 11, 2016.

- ↑ "Annual Report on Activities of the RSMC Tokyo – Typhoon Center 2000" (PDF). Japan Meteorological Agency. February 2001. p. 3. Retrieved August 11, 2016.

- ↑ "Destructive Typhoons 1970-2003". National Disaster Coordinating Council. November 9, 2004. Archived from the original on November 9, 2004. Retrieved August 11, 2016.

- ↑ Christopher W Landsea; Hurricane Research Division (April 26, 2004). "Subject: D4) What does "maximum sustained wind" mean? How does it relate to gusts in tropical cyclones?". Frequently Asked Questions:. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. Retrieved August 11, 2016.

- 1 2 3 Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 1985 IRMA (1985168N05156). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Retrieved August 11, 2016.

- ↑ "Storm bears down on Philippines". United Press International. June 26, 1985.

- ↑ "Typhoon Floods Parts of Manila". Association Press. June 26, 1985.

- 1 2 Alex Gaw (June 28, 1985). "Heavy rains lash Luzon". Association Press.

- 1 2 3 Miquel Suarez (June 28, 1985). "International News". Association Press.

- ↑ Martin Abuaggo (June 28, 1985). "Storms wreak havoc on the Philippines and Japan". United Press International.

- 1 2 "International News". Association Press. June 29, 1985.

- ↑ "13 Killed, Many Injured in Philippines Typhoon". Courier-Mail. June 29, 1985.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "International News". United Press International. June 30, 1985.

- 1 2 3 "Typhoon Hits Japanese Islands". Associated Press. July 1, 1985.

- 1 2 3 "Heavy Rains hit Kanto Area of Japan". Xinhua General Overseas News Service. July 1, 1985.

- ↑ "Typhoon causes havoc in swath across Japan". Eugene Register-Guard. July 2, 1985. Retrieved September 10, 2015.

- ↑ "Typhoon Slashes into Tokyo Buildings". Courier-Mail. July 1, 1985.

- ↑ Meteorological Results: 1985 (PDF) (Report). Hong Kong Royal Observatory. 1986. Retrieved August 11, 2015.