United States Naval Academy

| |

| Motto | Ex Scientia Tridens (Latin) |

|---|---|

Motto in English | From Knowledge, Sea Power |

| Type | US Service Academy |

| Established | October 10, 1845 |

Academic affiliations | APLU |

| Superintendent | VADM Walter E. Carter Jr. |

| Dean | Andrew T. Phillips |

Academic staff | 510 |

| Students | 4,576 midshipmen |

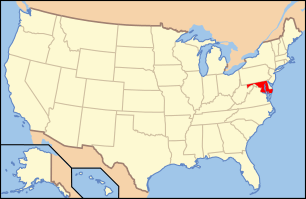

| Location | Annapolis, Maryland, United States |

| Campus | Urban – 338 acres (136.8 ha) |

| Colors |

Navy Blue and Gold |

| Nickname | Midshipmen |

| Mascot | Bill the Goat |

Sporting affiliations |

NCAA Division I – Patriot League CSFL EARC EIGL EIWA |

| Website | |

|

U.S. Naval Academy | |

| Location | Maryland Ave. and Hanover St., Annapolis, Maryland |

| Built | 1845 |

| Architect | Ernest Flagg |

| Engineer | Severud Associates |

| Architectural style | Beaux Arts[1] |

| NRHP Reference # | 66000386[2] |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | October 15, 1966 |

| Designated NHLD | July 4, 1961[3] |

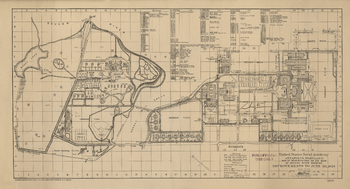

The United States Naval Academy (also known as USNA, Annapolis, or simply Navy) is a four-year coeducational federal service academy in Annapolis, Maryland, United States. Established on October 10, 1845, under Secretary of the Navy George Bancroft, it is the second oldest of the United States' five service academies, and educates officers for commissioning primarily into the United States Navy and United States Marine Corps. The 338-acre (137 ha) campus is located on the former grounds of Fort Severn at the confluence of the Severn River and Chesapeake Bay in Anne Arundel County, 33 miles (53 km) east of Washington, D.C. and 26 miles (42 km) southeast of Baltimore. The entire campus is a National Historic Landmark and home to many historic sites, buildings, and monuments. It replaced Philadelphia Naval Asylum, in Philadelphia, that served as the first United States Naval Academy from 1838 to 1845 when the Naval Academy formed in Annapolis.[4]

Candidates for admission generally must both apply directly to the academy and receive a nomination, usually from a Member of Congress. Students are officers-in-training and are referred to as midshipmen. Tuition for midshipmen is fully funded by the Navy in exchange for an active duty service obligation upon graduation. Approximately 1,200 "plebes" (an abbreviation of the Ancient Roman word plebeian) enter the Academy each summer for the rigorous Plebe Summer, but only about 1,000 midshipmen graduate. Graduates are usually commissioned as ensigns in the Navy or second lieutenants in the Marine Corps, but a small number can also be cross-commissioned as officers in other U.S. services, and the services of allied nations. The United States Naval Academy has some of the highest paid graduates in the country according to starting salary.[5] The academic program grants a bachelor of science degree with a curriculum that grades midshipmen's performance upon a broad academic program, military leadership performance, and mandatory participation in competitive athletics. Midshipmen are required to adhere to the academy's Honor Concept.

Description

The United States Naval Academy's campus is located in Annapolis, Maryland, at the confluence of the Severn River and the Chesapeake Bay.

In its 2016 edition, U.S. News & World Report ranked the U.S. Naval Academy as the No. 1 public liberal arts college and tied for the 9th best overall liberal arts college in the U.S.[6] In the category of High School Counselor Rankings of National Liberal Arts Colleges, the Naval Academy is also tied for No. 1 with the U.S. Military Academy and the U.S. Air Force Academy, and is tied for the No. 5 spot for Best Undergraduate Engineering program at schools where doctorates not offered.[6] In 2016, Forbes ranked the U.S. Naval Academy as No. 24 overall in its report "America's Top Colleges".[7]

Prospective candidates must either be nominated by certain public officials -- or be the child of a Medal of Honor recipient, which entitles a qualified candidate to automatic admission without nomination.[8] Nominations may be made by members of and delegates to Congress, the President or Vice-President, the Secretary of the Navy or certain other sources.[9] Candidates must also pass a physical fitness test and a thorough medical exam as part of the application process. In the 21st century, there have been about 1,200 students in each new class of plebes (freshmen).[10] The U.S. government pays for tuition, room, and board. Midshipmen receive monthly pay of $1,017.00, as of 2015.[11] From this amount, pay is automatically deducted for the cost of uniforms, books, supplies, services, and other miscellaneous expenses. Midshipmen only receive a portion of their total pay in cash while the rest is released during "firstie" (senior) year. Midshipmen fourth-class (plebes) to midshipmen second-class (juniors) receive monthly stipends of $100, $200, $300, respectively. Midshipmen first-class receive the difference between pay and outstanding expenses.

Students at the naval academy are addressed as Midshipman, an official military rank and paygrade. As midshipmen are actually in the United States Navy, starting from the moment that they raise their hands and affirm the oath of office at the swearing-in ceremony, they are subject to the Uniform Code of Military Justice, of which USNA regulations are a part, as well as to all executive policies and orders formulated by the Department of the Navy. The same term comprises both males and females. Upon graduation, most naval academy midshipmen are commissioned as ensigns in the Navy or second lieutenants in the Marine Corps and serve a minimum of five years after their commissioning. If they are selected to serve as a pilot (aircraft), they will serve 8–11 years minimum from their date of winging, and if they are selected to serve as a naval flight officer they will serve 6–8 years. Foreign midshipmen are commissioned into the armed forces of their native countries.

Since 1959, midshipmen have also been eligible to "cross-commission," or request a commission in the Air Force or Army, provided they meet that service's eligibility standards. Starting in 2004, midshipmen also became eligible to seek Coast Guard commissions. Every year, a small number of graduates do this—typically three or four—usually in a one-for-one "trade" with a similarly inclined cadet or midshipman at one of the other service academies.

At the beginning of their second-class year, midshipmen make their commitment, also known as signing their "2-for-7." This represents a commitment to finish two years at the academy and then an additional five years on active duty. Upon graduation, midshipmen are obligated to serve at minimum 5 years of service after graduation. Those selected for post-graduate education will continue concurrently with their commissioning obligation for officers in the U.S. Navy and consecutively for officers in the U.S. Marine Corps.

Midshipmen who entered the academy from civilian life and who resign or are separated from the academy in their first two years incur no military service obligation. Those who are separated—voluntarily or involuntarily – after that time are required to serve on active duty in an enlisted capacity, usually for two to four years. Alternatively, separated former midshipmen can reimburse the government for their educational expenses, though the sum is often in excess of $150,000. The decision whether to serve enlisted time or reimburse the government is at the discretion of the Secretary of the Navy. Midshipmen who entered the academy from the enlisted ranks return to their enlisted status to serve the remainder of their enlistment.

Other navy schools

The Navy operates the Naval Postgraduate School and the Naval War College separately. The Naval Academy Preparatory School (NAPS), in Newport, Rhode Island, is the official prep school for the Naval Academy. The Naval Academy Foundation provides post-graduate high school education for a year of preparatory school before entering the academy for a very limited number of applicants. There are several preparatory schools and junior colleges throughout the United States that host this program.[12]

History

Identity

The academy's Latin motto is Ex Scientia Tridens, Which means "Through Knowledge, Sea Power." It appears on a design devised by the lawyer, writer, editor, encyclopedist and naval academy graduate (1867), Park Benjamin, Jr. It was adopted by the Navy Department in 1898 due to the efforts of another graduate (also 1867) and collaborator, Jacob W. Miller. Benjamin states:[13]

"The seal or coat-of-arms of the Naval Academy has for its crest a hand grasping a trident, below which is a shield bearing an ancient galley coming into action, bows on, and below that an open book, indicative of education, and finally bears the motto, 'Ex Scientia Tridens' (From knowledge, sea power)."

The trident, emblem of the Roman god Neptune, represents seapower.

Early years

The institution was founded as the Naval School on October 10, 1845 by Secretary of the Navy George Bancroft. The campus was established at Annapolis on the grounds of the former U.S. Army post Fort Severn. The school opened with 50 midshipman students and seven professors. The decision to establish an academy on land may have been in part a result of the Somers Affair, an alleged mutiny involving the Secretary of War's son that resulted in his execution at sea. Commodore Matthew Perry had a considerable interest in naval education, supporting an apprentice system to train new seamen, and helped establish the curriculum for the United States Naval Academy. He was also a vocal proponent of modernization of the navy.

Originally a course of study for five years was prescribed. Only the first and last were spent at the school with the other three being passed at sea. The present name was adopted when the school was reorganized in 1850 and placed under the supervision of the chief of the Bureau of Ordnance and Hydrography. Under the immediate charge of the superintendent, the course of study was extended to seven years with the first two and the last two to be spent at the school and the intervening three years at sea. The four years of study were made consecutive in 1851 and practice cruises were substituted for the three consecutive years at sea. The first class of naval academy students graduated on 10 June 1854.

In 1860, the Tripoli Monument was moved to the academy grounds. Later that year in August, the model of the USS Somers experiment was resurrected when the USS Constitution, then 60 years old, was recommissioned as a school ship for the fourth-class midshipmen after a conversion and refitting begun in 1857. She was anchored at the yard, and the plebes lived on board the ship to immediately introduce them to shipboard life and experiences.[14]

The American Civil War

The Civil War was disruptive to the Naval Academy. Southern sympathy ran high in Maryland. Although riots broke out, Maryland did not declare secession. The United States government planned to move the school, when the sudden outbreak of hostilities forced a quick departure. Almost immediately the three upper classes were detached and ordered to sea, and the remaining elements of the academy were transported to Fort Adams in Newport, Rhode Island by the USS Constitution in April 1861, where the academy was set up in temporary facilities and opened in May.[15] The Annapolis campus, meanwhile, was turned into a United States Army Hospital.[16]

The United States Navy was stressed by the situation as 24% of its officers resigned and joined the Confederate States Navy, including 95 graduates and 59 midshipmen,[14] as well as many key leaders involved with the founding and establishment of USNA. The first superintendent, Admiral Franklin Buchanan, joined the Confederate States Navy as its first and primary admiral. Captain Sidney Smith Lee, the second commandant of midshipmen,[17] and older brother of Robert E. Lee, left Federal service in 1861 for the Confederate States Navy. Lieutenant William Harwar Parker, CSN, class of 1848, and instructor at USNA, joined the Virginia State Navy, and then went on to become the superintendent of the Confederate States Naval Academy. Lieutenant Charles “Savez” Read may have been "anchor man" (graduated last) in the class of 1860, but his later service to the Confederate States Navy included defending New Orleans, service on CSS Arkansas and CSS Florida, and command of a series of captured Union ships that culminated in seizing the US Revenue Cutter Caleb Cushing in Portland, Maine. Lieutenant James Iredell Waddell, CSN, a former instructor at the US Naval Academy, commanded the CSS Shenandoah. The first superintendent of the United States Naval Observatory, advocate[18] of the creation of the United States Naval Academy, after whom Maury Hall is named, similarly served in the Confederate States Navy.

The midshipmen and faculty returned to Annapolis in the summer of 1865, just after the war ended.

From the Civil War to World War I

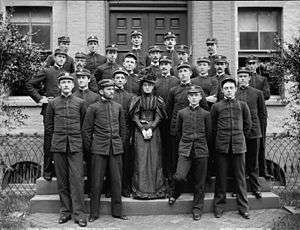

Civil War hero, Admiral David Dixon Porter became superintendent in 1865. He found the infrastructure at Annapolis a shambles, the result of ill military use during the War. Porter attempted to restore the facilities. He concentrated on recruiting naval officers as opposed to civilians, a change of philosophy. He recruited teachers Stephen B. Luce, future admirals Winfield Scott Schley, George Dewey, and William T. Sampson. He reinstated Professor Lockwood. The midshipman battalion consisted of four companies. They held dress parades every evening except Sunday. Students were termed "cadets", though sometimes "cadet midshipmen"; other appellations were used. Porter began organized athletics, usually intramural at the time.[19]

Antoine Joseph Corbesier immigrated from Belgium and was appointed to the position of Swordmaster at USNA in October 1865. He coached Navy fencers in intercollegiate competition between 1896 and 1914. By special act of Congress, he was commissioned a 1st Lieutenant in the Marine Corps on 4 March 1914. He died on 26 March 1915 and is buried on Hospital Point.

In 1867, indoor plumbing and water was supplied to the family quarters. In 1868, the figurehead from the USS Delaware, known as "Tecumseh" was erected in the yard. Class rings were first issued in 1869. Weekly dances were held. Wags called the school "Porter's Dancing Academy." President U.S. Grant distributed diplomas to the class of 1869.[19] Porter ensured continued room for expansion by overseeing the purchase of 113 acres (46 ha) across College Creek, later known as hospital point.

In 1871, color competition began, along with the selection of the color company, and a "color girl."[19]

In the 1870s, cuts in the military budget resulted in graduating much smaller classes. In 1872, 25 graduated. Eight of these made the Navy a career.[19] The third class physically hazed the fourth class so ruthlessly that Congress passed an anti-hazing law in 1874. Hazing continued in more stealthy forms.[19]

John H. Conyers of South Carolina was the first black admitted on September 21, 1872.[20] After his arrival, he was subject to severe, ongoing hazing, including verbal torment, and beatings. His classmates even attempted to drown him.[21] Three cadets were dismissed as a result, but the abuse, including shunning, continued in more subtle forms and Conyers finally resigned in October 1873.[22]

In 1875, Albert A. Michelson, class of 1873, returned to teach. He began his experiments with optics and the physics of light, which resulted in the first accurate measure of the speed of light.[23] [19]

In 1874, the curriculum was altered to study naval topics in the final two years at the academy. In 1878, the academy was awarded a gold medal for academics at the Universal Exposition in Paris.[19]

The Spanish–American War of 1898 greatly increased the academy's importance and the campus was almost wholly rebuilt and much enlarged between 1899 and 1906.

On 23 August 1911, the Navy officers on flight duty at Hammondsport, New York, and Dayton, Ohio, were ordered to report for duty at the Engineering Experiment Station, Naval Academy, "in connection with the test of gasoline motors and other experimental work in the development of aviation, including instruction at the aviation school" being set up on Greenbury Point, Annapolis.[24] Naval flight training moved to NAS Pensacola, Florida, in January 1914.[25]

In 1912, the Reina Mercedes, sunk at the Battle of Santiago de Cuba, was raised and used as the "brig" ship for the academy.[26]

In 1914, the Midshipmen Drum and Bugle corps was formed and by 1922 it went defunct. They were revived in 1926.[27]

Many firsts for minorities occurred during this period. In 1877, Kiro Kunitomo, a Japanese citizen, graduated from the academy.[28][29] And then in 1879, Robert F. Lopez was the first Hispanic-American to graduate from the academy.

In the late 19th century, Congress required the academy to teach a formal course in hygiene, the only course required by Congress of any military academy. Tradition holds that a congressman was particularly disgusted by the appearance of a midshipman returned from cruise.

World War I to World War II

The navy rowing team won the gold medal at 1920 Summer Olympics Games held in Antwerp, Belgium. In 1923, The Department of Physical Training was established. The naval academy football team played the University of Washington in the Rose Bowl tying 14–14. In 1925, the second-class ring dance was started. In 1925, the Midshipmen Drum and Bugle Corps was formally reestablished.[27] In 1926, "Navy Blue and Gold", composed by organist and choirmaster J. W. Crosley, was first sung in public. It became a tradition to sing this alma mater song at the end of student and alumni gatherings such as pep rallies and football games, and on graduation day. In 1926, Navy won the national collegiate football championship title. In the fall of 1929, the Secretary of the Navy gave his approval for graduates to compete for Rhodes Scholarships. Six graduates were selected for that honor that same year. The Association of American Universities accredited the Naval Academy curriculum on 30 October 1930.

In 1930, the class of 1891 presented a bronze replica of Tecumseh to replace the deteriorating wooden figurehead that had been prominently displayed on campus.[19]

President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed into law an act of Congress (Public Law 73-21, 48 Stat. 73) on 25 May 1933 providing for the bachelor of science degree for Naval, Military, and Coast Guard Academies. Four years later, Congress authorized the superintendent to award a bachelor of science degree to all living graduates. Reserve officer training was re-established in anticipation of World War II in 1941.

The academy was certified in 1937 by the Middle States Association although with reservations about the academic climate.[30]

In 1939, the first Yard patrol boat arrived. These were used to train midshipmen in ship handling.[32]

In 1940, the academy stopped using the Reina Mercedes as a brig for disciplining midshipmen, and restricted them to Bancroft Hall, instead.[26]

In April 1941, superintendent Rear Admiral Russell Willson refused to allow the school's lacrosse team to play a visiting team from Harvard University because the Harvard team included a black player. Harvard's athletic director ordered the player home and the game was played on 4 April, as scheduled, which Navy won 12–0.[33]

A total of 3,319 graduates were commissioned during World War II. Dr. Chris Lambertsen held the first closed-circuit oxygen SCUBA course in the United States for the Office of Strategic Services maritime unit at the academy on 17 May 1943.[34][35] In 1945, A Department of Aviation was established. That year a Vice Admiral, Aubrey W. Fitch, became superintendent. The naval academy celebrated its centennial. During the century of its existence, roughly 18,563 midshipmen had graduated, including the class of 1946.[36]

World War II to present

The academy and its support facilities became part of the Severn River Naval Command from 1941 to 1962.[37]

An accelerated course was given to midshipmen during the war years which affected classes entering during the war and graduating later. The students studied year around. This affected the class of 1948 most of all. For the only time, a class was divided by academic standing. 1948A graduated in June 1947; the remainder, called 1948B, a year later.[30]

From 1946 to 1961, N3N amphibious biplanes were used at the academy to introduce midshipmen to flying.[38]

On 3 June 1949, Wesley A. Brown, the sixth African-American to enter the academy,[21] became the first to graduate, followed several years later by Lawrence Chambers, who would become the first African American graduate to make flag rank.[39]

The 1950 Navy fencing team won the NCAA national championship.

The Navy eight-man rowing crew won the gold medal at 1952 Summer Olympics in Helsinki, Finland. They were also named National Intercollegiate Champions.[40] In 1955, the tradition of greasing Herndon Monument for plebes to climb to exchange their plebe "dixie cup" covers (hats) for a midshipman's cover started.

In 1957, the Reina Mercedes, ruined by a hurricane, was scrapped.[26]

The 1959 fencing team won the NCAA national championship, and became the first to do so by placing first in all three weapons (foil, épée, and saber). All 3 fencers were selected for the 1960 Olympic team, as was head coach Andre Deladrier. The Navy-Marine Corps Memorial Stadium, funded by donations, was dedicated 26 September 1959.

Joe Bellino (class of 1961) was awarded the Heisman Trophy on 22 June 1960. In 1961, the Naval Academy Foreign Affairs Conference was started. The Department of the Interior designated the U.S. Naval Academy a National Historic Landmark on 21 August 1961.

The 1962 fencing team won the NCAA national championship.

In 1963, Roger Staubach, class of 1965, was awarded the Heisman Trophy.

In 1963, the academy changed from a marking system based on 4.0 to a letter grade. Midshipmen began referring to the statue of Tecumseh as the "god of 2.0" instead of "the god of 2.5", the former failing mark.[41]

The academy started the Trident Scholar Program in 1963. From 3 to 16 juniors are selected for independent study during their final year.[42]

Professor Samuel Massie became the first African-American faculty member in 1966. On 4 June 1969, the first designated engineering degrees were granted to qualified graduates of the class of 1969.[40] During the period 1968 to 1972, the academy moved beyond engineering to include more than 20 majors. In 1970, the James Forrestal Lecture was created. This has resulted in various leaders speaking to midshipmen, including Henry Kissinger, football coach Dick Vermeil, and Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia.[43]

The 1970s brought change. In 1972, Lieutenant Commander Georgia Clark became the first female officer instructor, and Dr. Rae Jean Goodman was appointed to the faculty as the first civilian woman. Later in 1972, a decision of the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia terminated compulsory chapel attendance, which had been in effect since 1853.[44] In September 1973, the library facility complex was completed and named for Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz class of 1905.

On 8 August 1975, Congress authorized women to attend service academies. The class of 1980 was inducted with 81 female midshipmen. In 1980, the academy included "Hispanic/Latino" as a racial category for demographic purposes; four women identified themselves as Hispanic in the class of 1981, and these women become the first Hispanic females to graduate from the academy: Carmel Gilliland (who had the highest class rank), Lilia Ramirez (who retired with the rank of commander), Ina Marie Gomez, and Trinora Pinto.[45] In 1979, "June Week" was renamed "Commissioning Week" because graduation had moved to May.[40]

In May 1980, Elizabeth Anne Belzer (later Rowe) became the first woman graduate. On 23 May 1984, Kristine Holderied became the first woman to graduate at the head of the class. In addition, the class of 1984 included the first naturalized Korean-American graduates, all choosing commissions in the U.S. Navy. The four Korean-American ensigns were Walter Lee, Thomas Kymn, Andrew Kim, and Se-Hun Oh.

On 30 July 1987, the Computing Sciences Accreditation Board (CSAB) granted accreditation for the Computer Science program.[40] In 1991, Midshipman Juliane Gallina, class of 1992, became the first woman brigade commander. On 29 January 1994, the first genderless service assignment was held. All billets were opened equally to men and women with the exception of special warfare and submarine duty.

On 12 March 1995, Lieutenant Commander Wendy B. Lawrence, class of 1981, became a mission specialist in the space shuttle Endeavour. She is the first woman USNA graduate to fly in space.

To celebrate the 150th Anniversary of the U.S. Naval Academy at Annapolis (1845–1995), the U.S. Post Office printed a postage stamp; the First Day of Issue was 10 October 1995.

Freedom 7, America's first space capsule, was placed on display at the visitor center as the centerpiece of the "Grads in Space" exhibit on 23 September 1998. The late Rear Admiral Alan Shepard, class of 1945, had flown Freedom 7 116.5 miles (187.5 km) into space on 5 May 1961. His historic flight marked America's first step in the space race.[40]

On 11 September 2001, the academy lost 14 alumni in the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center and The Pentagon. The academy was placed under unprecedented high security.[40]

In August 2007, Superintendent Vice Admiral Jeffrey Fowler changed academy policy to limit liberty, required more squad interaction to emphasize that "we are a nation at war."[46]

On 3 November 2007, the navy football team defeated long-time rival Notre Dame for the first time in 43 years – 46–44 in triple overtime. The two teams have met every year since 1926 and continue a rivalry that became amicable when Notre Dame volunteered to open its facilities for training of naval officers in World War II.[47] The Navy was credited with saving the University of Notre Dame after its enrollment fell during World War II to about 250 students. The navy trained 12,000 men to become officers.[48]

In November 2007, Memorial Hall was the venue for a 50-nation Annapolis Conference on a Palestinian-Israeli peace process.

Rank structure

The student body is known as the Brigade of Midshipmen. Students attending the U.S. Naval Academy are appointed to the rank of midshipman and serve on active duty in that rank. Naval Academy midshipmen are classified as officers of the line, though their exercise of authority is limited by their training status.[49] Legally, midshipmen are a special grade of officer that ranks between warrant officer (W-1) and the lowest grade of chief warrant officer (W-2). However, midshipmen are not entrusted or authorized to exercise Title 10 or Title 50 authority as specified in United States Code.[49][50]

Midshipmen are classified not as freshmen, sophomores, juniors, and seniors, but as fourth class, third class, second class, and first class.

A member of the entering class—the fourth class, the lowest rank of midshipmen—is also known as a "plebe" (plural plebes). Because the first year at the Academy is one of transformation from a civilian into a military officer, plebes must conform to a number of rules and regulations not placed on their seniors—the upper three classes of midshipmen—and have additional tasks and responsibilities that disappear upon promotion to midshipman third class.

Third class midshipmen have been assimilated into the brigade and are treated with more respect because they are upperclassmen. They are commonly called "youngsters." Because of their new stature and rank, the youngsters are allowed such privileges as watching television, listening to music, watching movies, and napping.

Second class midshipmen are charged with training plebes. They report directly to the first class, and issue orders as necessary to carry out their responsibilities. Second class midshipmen are allowed to drive their own cars (but may not park them on campus) and are allowed to enter or exit the Yard (campus) in civilian attire (weekends only).

First class midshipmen have more freedoms and liberty in the brigade, and the most challenging responsibilities. While they must participate in mandatory sports and military activities and maintain academic standards, they are also charged with the leadership of the Brigade. They are commonly called "firsties". Firsties are allowed to park their cars on campus and have greater leave and liberty privileges than any other class.[51]

The Brigade is divided into two regiments of three battalions each. Five companies make up each battalion, for a total of 30 companies. The midshipman command structure is headed by a first class midshipman known as the brigade commander, chosen for outstanding leadership performance. He or she is responsible for much of the brigade's day-to-day activities as well as the professional training of midshipmen. Overseeing all brigade activities is the commandant of midshipmen, an active-duty Navy captain or Marine Corps colonel. Working for the commandant, experienced Navy and Marine Corps officers are assigned as company and battalion officers.[52]

Uniforms

Midshipmen at the Academy wear service dress uniforms similar to those of U.S. Navy officers, with shoulder-board and/or sleeve insignia varying by school year or midshipman officer rank. All wear gold anchor insignia on both lapel collars of the service dress blue jacket. Shoulder boards, worn on summer white, service/full dress white, and dinner dress white uniforms as well as a "soft shoulder board" version on the white, button-up shirt of the service/full dress blue uniform have a gold anchor and a number of slanted stripes indicating year, except for midshipman first class whose have a single, horizontal stripe and midshipman officers (also first class), whose shoulder boards have a small gold star in place of the anchor and have 1 through 6 horizontal stripes indicating their position.

On the winter and summer working uniform shirt, a freshman (Midshipman Fourth Class or "plebe") wears no collar insignia, a sophomore (Midshipman Third Class or "Youngster") wears a single fouled anchor on the right collar point, a Junior (Midshipman Second Class) fouled anchors on each collar point, and a Senior (Midshipman First Class or "Firstie") wears fouled anchors with perched eagles. First class midshipmen in officer billets replace those devices with their respective midshipman officer collar insignia.

Midshipman officer collar insignia are a series of gold bars, from the rank of Midshipman Ensign (one bar or stripe) to Midshipman Captain (six bars or stripes) in the Brigade of Midshipmen at the U.S. Naval Academy.

Depending on the season, midshipmen wear Summer Whites or Service Dress Blues as their dress uniform, and summer working blues or winter working blues as their daily class uniform. In 2008, the first class midshipmen wore the service khaki as the daily uniform, but this option was repealed following the graduation of the class of 2011. First class midshipmen may wear their service selection uniform on second semester Fridays (i.e., naval aviator and naval flight officer selectees wear flight suits; submarine and surface warfare selectees wear coveralls or Navy Working Uniforms with their new command ballcaps; Marine Corps selectees wear MARPAT camouflage utilities). A unique uniform consisting of a Navy blue double-breasted jacket with brass buttons and high collar, blue or white high-rise trousers (white worn during Graduation Week), and duty belt with silver NA buckle, is worn for formal parades during spring and autumn parade seasons.

During commissioning week (formerly known as "June week"), the uniform is summer whites.

Campus

The campus (or "Yard") has grown from a 40,000 square metres (9.9 acres) Army post named Fort Severn in 1845 to a 1.37 square kilometres (340 acres), or 1,375,640 square metres (339.93 acres), campus in the 21st century. By comparison, the United States Air Force Academy is 73 square kilometres (18,000 acres) and United States Military Academy is 65 square kilometres (16,000 acres).

Halls and principal buildings

- Bancroft Hall is the largest building at the Naval Academy and the largest college dormitory in the world.[53] It houses all midshipmen. Open to the public are Memorial Hall, a midshipman-maintained memorial to graduates who have died during military operations, and the Rotunda, the ceremonial entrance to Bancroft Hall. The Commander-in-Chief's Trophy resides in the Rotunda while Navy is in possession of it.[54][55] It was named for the Academy's founder, Secretary of the Navy George Bancroft, and designed by Ernest Flagg.

- The Naval Academy Chapel, at the center of the campus, across from Herndon Monument, has a high dome that is visible throughout Annapolis.[56] Designed by Ernest Flagg. The chapel was featured on the U.S. Postal Service postage stamp honoring the Academy's 150th anniversary in 1995.[57] John Paul Jones lies in the crypt beneath the chapel.

- Commodore Uriah P. Levy Center and Jewish Chapel,[58] primarily funded with private donations, was dedicated on 23 September 2005. The chapel was named for Commodore Uriah P. Levy and houses a Jewish chapel, the honor board, ethics, character learning center, officer development spaces, a social director, and academic boards. Built featuring Jerusalem stone, the architecture of the exterior is consistent with nearby Bancroft Hall.

- Alumni Hall is the primary assembly hall for the Brigade of Midshipmen and has two dining facilities. It hosts various sporting events (including the men's and women's intercollegiate basketball games) and is used by alumni for reunions. The Bob Hope Performing Arts Center is located there.

- archives – see Nimitz Library (below)

- Armel-Leftwich Visitor Center—inside Gate 1 and attached to the Halsey Field House—houses the USNA Guide Service, the USNA Gift Shop, a 12-minute film, and various exhibits, including the Graduates in Space exhibit, a sample midshipman's room, a model of the USS Maryland (BB-46), and an exhibit on the life and times of John Paul Jones, who is buried in the crypt beneath the Naval Academy Chapel. Walking tours include five types of adult tours and two types of student tours.[59]

- Athletic Hall of Fame – see Lejeune Hall (below)

- Chauvenet Hall, housing the departments of mathematics, physics, and oceanography, was named for William Chauvenet, an early professor at the US Naval Academy.

- Dahlgren Hall contains a large multi-purpose room and a restaurant area. It was once used as an armory for the Academy and for drill purposes. It was named for John A. Dahlgren.

- The Dyer Tennis Clubhouse is used by the tennis team and contains locker rooms, offices, a racquet stringing room, a lounge, and a viewing deck overlooking the tennis courts. It was named for Vice Admiral George Dyer (Class of 1919).[60][61]

- Halsey Field House contains an indoor track, squash and tennis courts, five basketball courts, a 65 tatami dojo for Aikido/Judo, a climbing wall, and assorted athletic and workout facilities and offices.[62] Before construction of Alumni Hall, it was used by Navy basketball teams and was the site of midshipman assemblies. It was named for William F. Halsey, Jr.

- Hubbard Hall – used by the crew team – is a three-story building on Dorsey Creek, 250 yards (230 m) from the Severn River.[60] Also known as the Boat House, it was renovated in 1993 and now includes the Fisher Rowing Center. It was named for Rear Admiral John Hubbard (Class of 1870).[60][63]

- King Hall is the dining hall that seats the Brigade of Midshipmen together at one time. It was named for Ernest J. King. Daily fare ranges from eggs, to sandwiches, to prime rib and the annual crab feast.

- Lejeune Hall, built in 1982, contains an Olympic-class swimming pool and diving tower, a mat room for wrestling and hand-to-hand martial arts, and the Athletic Hall of Fame. Named for John A. Lejeune, it is the first USNA building to be named for a Marine Corps officer.[64][65]

- library – see Nimitz Library (below)

- Luce Hall, housing the departments of Professional Development and Leadership, Ethics, and Law, was named for Stephen Luce.

- MacDonough Hall contains a full-scale gymnastics area, two boxing rings, and alternate swimming pools. It was named for Thomas MacDonough.

- Mahan Hall contains a theater along with the old library in the Hart Room, which has now been converted into a lounge and meeting room. It was named for Alfred Thayer Mahan. Designed by Ernest Flagg.

- Maury Hall contains the departments of Weapons and Systems Engineering plus Electrical Engineering. It was named for Matthew Fontaine Maury. Designed by Ernest Flagg.

- Michelson Hall, housing the departments of Computer Science and Chemistry, was named for Albert A. Michelson, the first American to win the Nobel Prize in Physics.

- museum – see Preble Hall (below)

- The Nimitz Library contains the academy's library collection, the academy's archives (William W. Jeffries Memorial Archives), and the departments of Language Studies, Economics and Political Science. It was named for Chester W. Nimitz.

- The Officers' and Faculty Club and officers quarters spread around the Yard.

- Preble Hall houses the U.S. Naval Academy Museum.[66] It was named for Edward Preble. It maintains a collection of Naval Academy class rings from 1869 through to the present. Tradition dictates that the first deceased class member's ring is donated to the museum to represent that class in the official class ring display.

- Ricketts Hall contains the basketball, football, and lacrosse offices, the locker room for the varsity football team, and one of the academy's three "strength and conditioning facilities," where Midshipman athletes train.[60] It was named for Claude V. Ricketts.

- Rickover Hall houses the departments of Electrical Engineering, Computer Engineering, Mechanical Engineering, Naval Architecture and Ocean Engineering, Aeronautical and Aerospace Engineering. It was named for Hyman G. Rickover.

- The Robert Crown Sailing Center contains offices, team classrooms, locker rooms, and equipment repair and storage facilities. It also houses the ICSA College Sailing Hall of Fame. Also on display in the Hall are the Naval Academy's sailing trophies and awards.[67]

- Sampson Hall, housing the departments of English and History, was named for William T. Sampson. Designed by Ernest Flagg.

- visitor center – see Armel-Leftwich Visitor Center (above)

- Wesley Brown Field House houses physical education, varsity sports, intramural athletics, club sports, and personal-fitness programs and equipment. The cross country and track and field teams, the sprint football team, the women's lacrosse team, and sixteen club sports all use this building. It has a full-length, retractable football field. When the field is retracted, you can then use the 200-meter track (with hydraulically controlled banked curves) and three permanent basketball courts. It also has eight locker rooms and a medical facility. It was named for Wesley A. Brown, Class of 1949, who was the Academy's first African American graduate.

Monuments and memorials

- Gokoku-ji Bell. A copy of the original bell which was brought back to the United States in 1855 by Commodore Matthew Perry following his mission to Japan. The bell is placed in front of Bancroft Hall and rung in a semi-annual ceremony for each victory that Navy has registered over Army, to include one of the nation's oldest football rivalries, the Army–Navy Game. The current bell is an exact replica of the original, which the United States Navy returned to the people of Okinawa in 1987.[68]

- Tecumseh Statue. This statue is a bronze replica of the figurehead of ship-of-the-line USS Delaware. It was presented to the Academy by the Class of 1891. This bust, one of the most famous relics on the campus, is commonly known as Tecumseh. However, when it adorned the American man-of-war, it commemorated not Tecumseh but Tamanend, the revered Delaware chief who welcomed William Penn to America. The original wooden figurehead is in the Naval Academy fieldhouse. In times past, the bronze replica was considered a good-luck "mascot" for the midshipmen, who threw pennies at it and offered left-handed salutes whenever they wanted a 'favor', such as a sports win over West Point, spiritual help for examinations. It is also referred to as the god of 2.0 because 2.0 is the minimum passing GPA at USNA, and the mids offer pennies to Tecumseh to help achieve this. Today it is used as a morale booster during football weeks and on special occasions when Tecumseh is painted in themes to include super heroes, action heroes, humorous figures, a leprechaun (before Saint Patrick's Day) and a naval officer (during Commissioning Week).

- Battle ensigns. Famous flags of the U.S. Navy and captured flags from enemy ships are displayed throughout the academy. The most famous, perhaps, is the "Don't Give Up the Ship" flag flown by Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry at the Battle of Lake Erie on 10 September 1813; it bears the dying words of Captain James Lawrence, captain of the USS Chesapeake. It was displayed in Memorial Hall, which is in the portion of Bancroft Hall open to the general public until 2004. It underwent conservation and is now on display in the Museum in Preble Hall. The only British royal standard taken by capture was displayed in Mahan Hall. It was taken at Toronto (then York) in the War of 1812.

- Herndon Monument. The Monument was commissioned by the Officers of the U.S. Navy as a tribute to Commander William Lewis Herndon (1813–1857) after his loss in the Pacific Mail Steamer Central America during a hurricane off the North Carolina coast on 12 September 1857. Herndon had followed a longtime custom of the sea that a ship's captain is the last person to depart his ship in peril. It was erected in its current location on 16 June 1860 and has never been moved, even though the Academy was completely rebuilt between 1899 and 1908. Every year as part of the year end festivities, Herndon is covered with lard and plebes attempt to climb the monument, remove a "dixie cup" (the headwear of a plebe) and put a "cover" (the standard midshipman hat) on top. This symbolizes the successful completion of their first year. Legend also has it that the midshipman who places the sailors cap upon the monument will be the first member of the class to reach the rank of Admiral. In 2008, both the dixie cup removed and the cover placed on Herndon to end the climb belonged to Midshipman Kristen Dickmann, Class of 2011, who died a few days before the Herndon Climb. Midshipman Dickmann's dixie cup and cover were the first women's caps used for the Herndon Climb.[69]

- Memorial Hall – in Bancroft Hall – is a midshipman-kept memorial to graduates who died during military operations. It includes an honor roll, scrolls, and plaques.

- Pearl Harbor memorial. At Alumni Hall, a wall is reserved by the Pearl Harbor Survivors Association to commemorate those who were killed during the attack on Pearl Harbor.

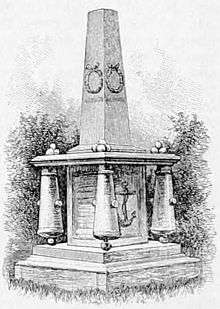

- Tripoli Monument – the oldest military monument in the U.S., honors the heroes of the First Barbary War: Master Commandant Richard Somers, Lieutenant James Caldwell, James Decatur (brother of Stephen Decatur), John Dorsey, Joseph Israel, and Henry Wadsworth. Originally known as the Naval Monument, it was carved of Carrara marble in Italy in 1806 and brought to the U.S. as ballast on board the USS Constitution ("Old Ironsides"). From its original location in the Washington Navy Yard, it was moved to the west terrace of the national Capitol and finally, in 1860, to the Naval Academy.[70]

- USS Samuel B. Roberts memorial. In Alumni Hall, a concourse is dedicated to Lieutenant Lloyd Garnett and his shipmates aboard USS Samuel B. Roberts, who earned their ship the reputation as the "destroyer escort that fought like a battleship" in the Battle of Leyte Gulf during World War II.

- The Mexican War Midshipmen's Monument at the intersection of Stribling Walk (16,000 bricks) and Chapel Walk is in memory of one midshipman (Shubrick) who lost his life in the siege of Veracruz in 1847, and three midshipmen (Clemson, Hynson, Pillsbury) who lost their lives when the brig Somers sank in 1846.[71]

- The Macedonian Monument, at the end of Stribling Walk opposite Mahan Hall, is the figurehead of HMS Macedonian. Macedonian was defeated in battle by the frigate United States 25 October 1812.

Brigade sports complex

The complex includes McMullen Hockey Arena where the men's ice-hockey team is located; rugby venues, an indoor hitting, chipping and putting facility for the golf team, and the Tose Family Tennis Center – including the Fluegel-Moore Tennis Stadium.[60]

Cemetery and columbarium

Glenn Warner Soccer Facility

Navy-Marine Corps Memorial Stadium

Terwilliger Brothers Field

The Academy baseball team plays at the Terwilliger Brothers Field at Max Bishop Stadium.

Supervision of the Academy

In 1850, the academy was placed under the jurisdiction of the Navy's Bureau of Ordnance and Hydrography but was transferred to the Bureau of Navigation when that organization was established in 1862. The academy was placed under the direct care of the Navy Department in 1867, but for many years the Bureau of Navigation provided administrative routine and financial management.

As of 2004, the Superintendent of the Naval Academy reports directly to the Chief of Naval Operations. The current Superintendent is Vice Admiral Walter E. Carter Jr.

The current Commandant of Midshipmen is Colonel Stephen E. Liszewski, USMC (USNA Class of 1990), a career artillery officer and the Academy's 86th Commandant.[72]

Faculty

Roughly 500 faculty members are evenly divided between civilian professors and military instructors. The civilian professors nearly all have a PhD and can be awarded tenure, usually upon promotion from assistant professor to associate professor. Fewer of the military instructors have a PhD but nearly all have a master's degree. Most of them are assigned to the Academy for only two or three years. Additionally, there are adjunct professors, hired to fill temporary shortages in various disciplines. The Adjunct Professors are not eligible for tenure.

- Permanent Military Professors (PMP)

A small number of officers at the Academy are designated as Permanent Military Professors (PMP), initially at the academic rank of Assistant Professor. All PMPs have PhDs, and remain at the Academy until statutory retirement. Most are commanders in the Navy; a few are captains. Like civilian professors, they seek academic promotion to the rank of Associate Professor and Professor. However, they are not eligible for tenure.

- Distinguished Visiting Professorships

The Class of 1957 Distinguished Chair of Naval Heritage is an academic professorial chair in the History Department.[73] In order to preserve and promote a better understanding of professional naval heritage in midshipmen at the U.S. Naval Academy, the Academy's Class of 1957 donated the funds to permanently endow this position. It is designed to be a visiting position for a distinguished senior academic historian, who is to hold the post for one or two years. The position was first occupied in 2006 and, in addition to teaching requirements, the occupant is expected to give the McMullen Seapower Lecture at the Academy's biennial McMullen Naval History Symposium.

Chair Holders

- Williamson Murray, January 2006 – June 2007

- Andrew Gordon, August 2007 – June 2009

- Ronald H. Spector, August 2009 – June 2010

- John H. Schroeder, August 2010 – June 2011

- Craig Symonds, August 2011 – June 2012

- James C. Bradford. August 2012 – June 2013

- Gene Allen Smith, August 2013 – June 2014

- William F. Trimble, August 2014 - June 2015

- David Alan Rosenberg, August 2015 -

Appointment process

By an Act of Congress passed in 1903, two midshipman appointments were allowed for each senator, representative, and delegate in Congress, two for the District of Columbia, and five each year at large. Currently each member of Congress and the Vice President can have five appointees attending the Naval Academy at any time. When any appointee graduates or otherwise leaves the academy, a vacancy is created. Candidates are nominated by their senator, representative, or delegate in Congress, and those appointed at large are nominated by the Vice President. The applicants do not have to know their Congressman to be nominated. Congressmen generally nominate ten people per vacancy. They can nominate people in a competitive manner, or they can have a principal nomination. In a competitive nomination, all ten applicants are reviewed by the academy, to see who is the most qualified. If the congressman appoints a principal nominee, then as long as that candidate is physically, medically, and academically found qualified by the academy, he or she will be admitted, even if there are more qualified applicants. The degree of difficulty in obtaining a nomination varies greatly according to the number of applicants in a particular state. The process of obtaining a nomination typically consists of completing an application, completing one or more essays, and obtaining one or more letters of recommendation and often requires an interview either in person or over the phone. These requirements are set by the respective senator or congressman and are in addition to the USNA application.[74]

The Secretary of the Navy may appoint 170 enlisted members of the Regular and Reserve Navy and Marine Corps to the Naval Academy each year. Additional sources of appointment are open to children of career military personnel (100 per year); and 65 appointments are available to children of military members who were killed in action, or were rendered 100% disabled due to injuries received in action, or are currently prisoners of war or missing in action. Typically five to ten candidates are nominated for each appointment, which are normally awarded competitively; candidates who do not receive the appointment they are competing for may still be admitted to the Academy as a qualified alternate. If a candidate is considered qualified but not picked up, they may receive an indirect admission to either a Naval Academy Foundation prep school or the Naval Academy Preparatory School in Newport; the following year, these candidates enlist in the Navy Reserve (or, in the case of prior enlisted members, remain in the Navy) and are eligible for Secretary of the Navy nominations, which are granted as a matter of course. To receive an appointment to the Naval Academy, students at the Naval Academy Preparatory School must first pass with a 2.2 QPA (A mix of GPA and Fitness Assessments), although this is waiverable. A candidate must receive a recommendation for appointment from the Commanding Officer. The appointment process has been criticized as giving preferential treatment towards athletes.[75]

However, children of Medal of Honor recipients are automatically appointed to the Naval Academy; they only need to meet admission requirements.[76]

Admissions requirements

To be admitted, candidates must be between seventeen and twenty-three years of age upon entrance, unmarried with no children, and of good moral character. The current process includes a college application, personality testing, standardized testing, and personal references. Candidates for admission must also undergo a physical aptitude test (the CFA or Candidate Fitness Assessment [formerly the Physical Readiness Examination]) as well as a complete physical exam including a separate visual acuity test to be eligible for appointment. A medical waiver will automatically be sought on behalf of candidates with less than 20/20 vision, as well as a range of other injuries or illnesses. The physical aptitude test is most often administered by a high school physical education teacher or sports team coach.[76]

A small number of international students, usually from smaller allied or friendly countries, are admitted into each class. (International students from larger allies, such as France and the United Kingdom, typically come as shorter-term exchange students from their national naval colleges or academies.) The Class of 2018 includes 13 international students from: Cambodia (1), Cameroon (2), Federated States of Micronesia (1), Georgia (1), Kazakhstan (1), Korea (1), Mexico (1), Montenegro (1), Nigeria (1), Senegal (1), Taiwan (1), and United Arab Emirates (1).[77]

In 2009 and 2010, a professor complained that less than qualified candidates were being admitted to the Academy.[78] His complaint has been forwarded to the Chief of Naval Operations.[79]

Curriculum

The Naval Academy received accreditation as an approved "technological institution" in 1930. In 1933, President Franklin Roosevelt signed into law an act of Congress providing for the Bachelor of Science Degree for the Naval, Military, and Coast Guard Academies. The Class of 1933 was the first to receive this degree and have it written in the diploma. In 1937, an act of Congress extended to the Superintendent of the Naval Academy the authority to award the Bachelor of Science degree to all living graduates. The Academy later replaced a fixed curriculum taken by all midshipmen with the present core curriculum plus 22 major fields of study.[80]

Academic departments at the Naval Academy are organized into three divisions: Engineering and Weapons, known as Division I, Mathematics and Science, known as Division II, and Humanities and Social Sciences, known as Division III.

Moral education

Moral and ethical development is fundamental to all aspects of the Naval Academy. From Plebe Summer through graduation, the Officer Development Program, a four-year integrated program, focuses on integrity, honor, and mutual respect based on the moral values of respect for human dignity, respect for honesty and respect for the property of others.[81]

One of the goals of the program is to develop midshipmen to possess a sense of their own moral beliefs and the ability to express them. Honor is emphasized through the Honor Concept of the Brigade of Midshipmen, which states:

Midshipmen are persons of integrity: They stand for that which is right.

They tell the truth and ensure that the full truth is known. They do not lie.

They embrace fairness in all actions. They ensure that work submitted as their own is their own, and that assistance received from any source is authorized and properly documented. They do not cheat.

They respect the property of others and ensure that others are able to benefit from the use of their own property. They do not steal.[82]

Similar ideals are expressed in the honor codes of the other service academies. However, midshipmen are allowed to confront someone they see violating the code without formally reporting it. It is believed that this method is a better way of developing the honor of midshipmen as opposed to the non-toleration clauses of the other service academies and is a better way of building honor and trust.

Brigade Honor Committees composed of upper-class midshipmen are responsible for the education and training of the Honor Concept. Depending on the severity of the offense, midshipmen found in violation of the Honor Concept by their peers can be separated from the Naval Academy.[81]

Naval Academy Foreign Affairs Conference (NAFAC)

Since 1961, the Academy has hosted the annual Naval Academy Foreign Affairs Conference (NAFAC), the country's largest undergraduate, foreign-affairs conference. NAFAC provides a forum for addressing pressing international concerns and seeks to explore current issues from both a civilian and military perspective.

Each year a unique theme is chosen for NAFAC. Noteworthy individuals with expertise in relevant fields are then invited to address the conference delegates, who represent civilian and military colleges from across the United States and around the globe.

The entire conference is organized and run by midshipmen, who also serve as moderators, presenters, and delegates. The midshipman director is responsible for every aspect of the conference, including the conference theme, and is generally charged with leading a staff of over 250 midshipmen.[83]

McMullen Naval History Symposium

Since 1973, the Naval Academy has hosted a major international conference for naval historians. In 2006 it was named after Dr. John J. McMullen, USNA Class of 1940.

Small Satellite Program

The United States Naval Academy (USNA) Small Satellite Program (SSP)[84] was founded in 1999 to actively pursue flight opportunities for miniature satellites designed, constructed, tested, and commanded or controlled by midshipmen.

The USNA MidSTAR Program's first satellite, MidSTAR I was launched 8 March 2007.[85] The planned MidSTAR II was canceled.

Postgraduate Studies

Because the majority of graduates commence directly into their military commissions, the Naval Academy offers no graduate degree programs. However, a number of programs allow midshipmen to obtain graduate degrees before fulfilling their service obligation. The Immediate Graduate Education Program (IGEP) allows newly commissioned Ensigns or Second Lieutenants to proceed directly to graduate school and complete a master's degree. The Voluntary Graduate Education Program (VGEP) allows the midshipman to begin his studies the second semester of his senior year at a local university, usually University of Maryland, Johns Hopkins University, Georgetown University, or George Washington University, and complete the degree by the following semester. Midshipmen accepted into prestigious scholarships, such as the Rhodes Scholarship are permitted to complete their studies before fulfilling their service obligation. Finally, the Bowman Scholarship allows Navy Nuclear Power candidates to complete master's degrees at the Naval Postgraduate School before continuing into the Navy.

Student activities

Athletics

Participation in athletics is, in general, mandatory at the Naval Academy and most midshipmen not on an intercollegiate team must participate actively in intramural or club sports. There are exceptions for non-athletic Brigade Support Activities such as YP Squadron (a professional surface warfare training activity providing midshipmen the opportunity to earn the Craftmaster Badge) or the Drum and Bugle Corps.

Varsity-letter winners wear a specially issued blue cardigan with a large gold "N" patch affixed. Teams that beat Army in a year are awarded a gold star to affix near the "N" for each such victory.

The U.S. Naval Academy's varsity sports teams[86] have no official name but usually are referred to in media as "the Midshipmen" (since all athletes are, in fact, midshipmen), or more informally as "the Mids". The term "middies" is generally considered derogatory.[87] The sports teams' mascot is a goat named "Bill."

The Midshipmen participate in the NCAA's Division I FBS as a member of the American Athletic Conference in football and in the NCAA Division I-level Patriot League in many other sports. The academy fields 30 varsity sports teams and 13 club sports teams (along with 19 intramural sports teams).[86][88]

The most important sporting event at the academy is the annual Army–Navy Game, in football. The 2015 season marks Navy's 14th consecutive victory over Army. The three major service academies (Navy, Air Force, and Army) compete for the Commander-in-Chief's Trophy, which is awarded to the academy that defeats the others in football that year (or retained by the previous winner in the event of a three-way tie). Navy won the trophy in 2012 after two years of residence at the Air Force Academy. Keenan Reynolds (Quarterback 2012-2015) set numerous Navy and NCAA records, including the FBS career rushing touchdown record, arguably becoming Navy's best quarterback ever. Reynolds finished fifth in the prestigious Heisman Trophy voting. In the Army-Navy rivalry, Reynolds became the first quarterback to beat Army in four seasons.[89]

Naval Academy sports teams have many accomplishments at the international and national levels. In 1926, Navy's football team won the U.S. national championship based on both the Boand and Houlgate mathematical poll systems.[90] and the Navy men's lacrosse team won 21 USILL or USILA national championships and was the NCAA Division I runner-up in 1975 and 2004. The men's fencing team won NCAA Division I championships in 1950, 1959, and 1962 and was runner-up in 1948, 1953, 1960, and 1963,[91] and NCAA Division I championships were also earned by the 1945 men's outdoor track and field team[92] and the 1964 men's soccer team.[93]

The Academy lightweight crew won the 2004 National Championship. The lightweights are accredited with two Jope Cup Championships as well, finishing the Eastern Sprints with the highest number of points in 2006 and 2007. The college's heavyweight crew won Olympic gold medals in men's eights in 1920 and 1952,[94] and from 1907 to 1995 at Intercollegiate Rowing Association regatta the team earned 30 championships.[95] In intercollegiate shooting, the Naval Academy has won nine National Rifle Association rifle team trophies, seven air pistol team championships, and five standard pistol team titles.[96] Navy's squash team was the national nine-man team champion in 1957, 1959, and 1967,[97] and the boxing team was National Collegiate Boxing Association champion in 1987, 1996, 1997, 1998, and 2005.[98]

There is an unofficial (but previous National Champion) croquet team.[99] Legend has it that in the early 1980s, a Mid and a Johnnie (slang for a student enrolled at St. John's College, Annapolis), were in a bar and the Mid challenged the Johnnie by stating that Midshipmen could beat St. John's at any sport. The St. John's student selected croquet. Since then, thousands attend the annual croquet match between St. John's and the 28th Company[100] of the Brigade of Midshipmen (originally the 34th Company before the Brigade was reduced to 30 companies). As of 2006,[101] the Midshipmen had a record of 5 wins and 19 losses to the St John's team.

Song

- See also: #Naval Academy traditions (below)

Notable among a number of songs commonly played and sung at various events such as commencement and convocation, and athletic games is: “Anchors Aweigh”, the United States Naval Academy fight song. According to “College Fight Songs: An Annotated Anthology” published in 1998, “Anchors Aweigh" ranks as the fifth greatest fight song of all time.

Other extra-curricular activities

Midshipmen have the opportunity to participate in a broad range of other extracurricular activities including musical performance groups (Drum & Bugle Corps, Men's Glee Club, Women's Glee Club, Gospel Choir, an annual musical, a midshipman orchestra, and a bagpipe band, the Pipes & Drums), religious organizations, academic honor societies such as Omicron Delta Epsilon (an economics honor society), Campus Girl Scouts, the National Eagle Scout Association, a radio station (WRNV),[102] and Navy and Marine Corps professional activities (diving, flying, seamanship, and the Semper Fidelis Society for future Marines). The midshipman theatrical company, The Masqueraders, put on one production annually in Mahan Hall. There is an intercollegiate debate team.[103] Colleges from along the East Coast attend the annual U.S. Naval Academy Debate Tournament. Midshipmen also participate in the Sandhurst Competition, a military skills event.[104]

The Brigade began publishing a humor magazine called The Log in 1913.[105] This magazine was discontinued in 2001[106] but returned to print in the fall of 2008. Among The Log's usual features were "Salty Sam," an anonymous member of the senior class who served as a gossip columnist, and the "Company Cuties," photos of male midshipmen's girlfriends. (This last was deemed offensive to women, and despite attempts to incorporate the boyfriends of female midshipmen in some issues, the "Company Cuties" were dropped from The Log's format by 1991.)[107] The Log was once featured in Playboy Magazine for its parody of the famous periodical,[108] called "Playmid." "Playmid" was an issue of The Log in 1989 and was ordered destroyed by Rear Admiral Virgil I. Hill, the Academy Superintendent at the time, but a handful of copies did survive, including the one which later showed. Earlier Log attempts to parody were much more successful, with the 18 April 1969, version as the most famous; some sections of this issue can be seen online at an alumni website.[109] In September 1949, the Log began publishing a half-sized Splinter bi-weekly, to alternate with its larger sized publication.[110][111][111]

Naval District Washington Police Department

The NDW Police Department-US Naval Academy is a full-service law enforcement agency responsible for policing the US Naval Academy complex.[112]

Women at the Naval Academy

The Naval Academy first accepted women as midshipmen in 1976, when Congress authorized the admission of women to all of the service academies. Women comprise about 22 percent of entering plebes.[113] They pursue the same academic and professional training as do their male classmates, except that certain physical aptitude standards for women are lower than for men, mirroring the standards of the Navy itself. Women have most recently composed about 17 percent of each graduating class, however this number continues to rise. The first pregnant midshipman graduated in 2009. While regulations expressly forbade this, the woman was able to receive a waiver from the Department of the Navy.[114]

In 2006, Michelle J. Howard, class of 1982, became the first female graduate of the Naval Academy to be selected for admiral; she was also the first admiral from her class. Margaret D. Klein, class of 1981, became the first female commandant of midshipmen in December 2006.

Following the 2003 U.S. Air Force Academy sexual assault scandal and due to concern with sexual assault in the U.S. military the Department of Defense was required to establish a task force to investigate sexual harassment and assault at the United States military academies in the law funding the military for fiscal 2004. The report, issued 25 August 2005 showed that during 2004 50% of the women at Annapolis reported instances of sexual harassment while 99 incidents of sexual assault were reported.[115] There had been an earlier incident in 1990 which involved male midshipmen chaining a female midshipman to a urinal and then taking pictures of her after she threw a snowball at them.[116]

Academy Superintendent Vice Admiral Rodney Rempt issued a statement: "With the benefit of the Defense Task Force's assessment and recommendations, we will continue to strive to establish a climate which encourages reporting of these incidents, so we can support the victim and deal with allegations fairly and appropriately. The very idea that any member of the Naval Academy family could be part of an environment that fosters sexual harassment, misconduct, or even assault is of great concern to me, and it is contrary to all we are trying to do and achieve. Preventing and deterring this unacceptable behavior is a leadership issue that I and all the Academy leaders take to heart. The public trusts that the Service Academies will adhere to the highest standards and that we will serve as beacons that exemplify character, dignity and respect. We will increase our efforts to meet that trust." Superintendent Rempt has recently been criticized for not allowing former Navy quarterback Lamar Owens to graduate, despite his acquittal on a rape charge. Some alumni have attributed this to an overeagerness on Rempt's part to placate critics urging a crackdown on sexual assault and harassment.[117]

In 1979, James H. Webb published a provocative essay opposing the integration of women at the Naval Academy titled "Women Can't Fight." Webb was an instructor at the Naval Academy in 1979 when he wrote the article for Washingtonian magazine that was critical of women in combat and of them attending the service academies. The article, in which he referred to the dorm at the Naval Academy that housed 4,000 men and 300 women as "a horny woman's dream," was written three years after the Academy admitted women. Webb said he did not write the headline.[118]

On 7 November 2006, Webb was elected to the U.S. Senate from Virginia. His election opponent, then senator George Allen, raised the 1979 article as a campaign issue, depicting Webb as being opposed to women in military service. Webb's response read in part, "I am completely comfortable with the roles of women in today's military. ... To the extent that my writings subjected women at the Academy or the active armed forces to undue hardship, I remain profoundly sorry."[119] In a political advertisement for Allen five female graduates of the United States Naval Academy said the article helped foster an air of hostility and harassment towards females within the academy.

The Navy Secretary Ray Mabus on December 21, 2012, issued a statement of shame over a recent sexual abuse study which showed the nation's service academies continue to have trouble maintaining safe teaching environments regarding sexual abuse. Reported sexual assaults last year declined from 22 to 13 at Annapolis. The superintendent, Vice Admiral Mike Miller, has enforced a new academy policy, as of January 2013, related to training, victim support, campus security, leadership presence on weekends, and a general review of alcohol policy based on other information in the recent report which shows the actual number of sexual assaults has not declined and that offenses are not reported.[120]

Naval Academy traditions

|

"Anchors Aweigh" (historical)

1929 acetate recording performance of "Anchors Aweigh" by the United States Navy Band. Anchors Aweigh (modern)

An instrumental sample of a single verse of Anchors Aweigh played by a modern brass band. |

| Problems playing these files? See media help. | |

Some traditions have been around for a century or more. Some traditions of the Naval Academy are handed down from class to class. Some have been recorded over the years in academy publications.

- Anchors Aweigh – written by 2nd Lieutenant Zimmerman, USMC, bandmaster of the Naval Academy Band starting in 1887, wrote the song "Anchors Aweigh" and dedicated it to the Naval Academy Class of 1907. The song is sung during sporting events, pep rallies, and played by the Drum and Bugle Corps during noon meal formations. Members of the Navy and Marine Corps, unless marching, are supposed to come to attention while it is playing. The original verse (quoted below) is learned by midshipmen as plebes. The second verse is now most commonly sung.:[121]

Stand Navy down the field, sails set to the sky. We'll never change our course, so Army you steer shy-y-y-y. Roll up the score, Navy, Anchors Aweigh. Sail Navy down the field and sink the Army, sink the Army Grey.[121]

- "Beat Army" is a common phrase, most often said after the singing of the Academy's Alma Mater, "Blue and Gold." The phrase is commonly said by plebes while squaring corners. Furthermore, if one is said to have a Beat Army, it means the person drank a stomach-turning concoction of any number of condiments and food at that particular meal. Most often done by plebes to impress upperclass, they scream "BEAT ARMY!" when they are done drinking the beverage, usually to applause.

- "Blue and Gold" is the name of Naval Academy's Alma Mater.[121] The song is sung at the conclusion of every sporting event, at the end of pep rallies and at alumni gatherings. It is also sung in most companies by the plebes at the conclusion of the day; this event is also referred to as "Blue and Gold," which is a short gathering to review the day for better or worse with the upperclass midshipmen. The original lyrics are:

Blue and Gold

Now college men from sea to sea may sing of colors true,

But who has better right than we, to hoist a symbol hue,

For sailor men in battle fair, since fighting days of old,

Have proved the sailor's right to wear, the Navy Blue and Gold!

"Beat Army!"

Actual Words: United States Naval Academy Lucky Bag 1985, pp. 790–797

- The second verse is sung at each graduation and commissioning ceremony and is often performed by the Glee Clubs.

Four years together by the bay where Severn joins the tide,

And by the service called away we scatter far and wide.

But still when two or three shall meet and old tales be retold,

From low to highest in the Fleet, we'll pledge the Blue and Gold!

- The lyrics were changed in 2004 to make them gender neutral. The current lyrics sung today are:

Blue and Gold

Now colleges from sea to sea may sing of colors true,

But who has better right than we, to hoist a symbol hue?

For sailors brave in battle fair, since fighting days of old,

Have proved the sailor's right to wear, the Navy Blue and Gold!

"Beat Army!"[121]

- Cover Toss – Midshipmen who graduate to become ensigns in the Navy or second lieutenants in the Marine Corps toss their midshipman covers (hats) at graduation in a farewell bid to the three classes below them. Various traditions have been used regarding something to put into the cover, such as putting a small sum of money inside the cover so children attending can collect the covers and money, or putting your name and address inside to receive a letter and cake. Today, the most common tradition is simply leaving a small sum of money for the recipient of the cover. The Cover Toss tradition started in 1912.

- Goat Court[122] refers to two completely enclosed square sections inside the third and fourth wings of Bancroft, composed of five stories of room windows. The bottom of the courts are composed of the roof of the basement level. The rooms are commonly assigned to Plebes or short-straw drawing Youngsters, since they lack the view that many other rooms have. The air is stagnant, and the large HVAC units on the basement roof detract from the ambiance.[123]

- Herndon Monument Climb (see above, under "Monuments and Memorials") – the official end of plebe year at the Naval Academy when the plebes raise a classmate to replace a dixie cup sailor cover with the combination cover traditional to midshipmen.[122][124][125][126]

- The Jimmy Legs[127] were the civilian patrolmen or masters-at-arms who provided security for the Naval Academy grounds, and were referred to by that name as far back as an entry in the 1923 Lucky Bag. The name stems from old 19th century Navy use of calling the shipboard master-at-arms by that name, since they often yelled out "shake a leg" or "clear the deck" to maintain discipline and prevent unwanted gatherings on board the ship. Not to be confused with the Jimmy Legs, the U.S. Marines have had brief periods of duty guarding the Yard.

- The Laws of the Navy – a poem of wise advice in the form of twenty-seven laws, often memorized and less often applied, composed by Rear Admiral Ronald Hopwood, Royal Navy, and originally appearing in the Army and Navy Gazette, 23 July 1896. By the mid-1920s the poem began appearing in the USNA's Reef Points, the official midshipman handbook and training manual issued to all freshman plebes during their induction to the school.[128]

- Red Beach[126][129] – the red tiled plaza behind Memorial Hall on top of the wardroom in between 5th and 6th wings of Bancroft Hall, used as a place of formation for part of the Brigade. It also serves as a place for restrictees to march tours. During warm weather this area in the past served as a place for midshipmen to sun bathe which is where the name "red beach" is derived.

- Ring Dance – held in May, this event is when the second class midshipmen receive their class rings at a formal dance complete with fireworks. The event is held in Dahlgren Hall. Traditionally, the Midshipman's date wears the ring around her/his neck, and the couple dips the ring in water from all seven seas.[122][124][125][126]

- Salty Sam – is the personification of the reformation movement in the United States Navy through her Naval Academy graduates.[130] Spiritually the first Salty Sam was perhaps the "natural leader of the navy's Young Turks"[131] William Sims (Class of 1880), who became the leading reformer of the Navy, retiring as a full admiral.

Many of his letters today are relished not because of the reforms there advocated but because of the hilarious way he presented them ... he was addicted to poetry as a means of expression; he put forth his ideas in rhyme whenever possible, sometimes to the despair of his more serious fellows – but others were occasionally enticed to respond in kind. The war on paper could well be waged in poetry, he felt, for it at least kept the mind higher. The older and more senior he became, the more would he try to lighten the mood of his cohorts by humor in prose and poetry, though the latter, many said, became increasingly atrocious the more elevated its author's naval rank. Still it served its purpose admirably. As a junior officer it was a way to cloak his ideas in a patina of genteel wardroom horseplay, with the barb of criticism perfunctorily covered.

— Capt. Edward L. Beach, USN[131]

- In later years Salty Sam led the enlightenment of Sims through The Log at USNA. Salty Sam reflects the spirit of Sims by questioning today's paradigms to ready the Navy for the future. The secret and anonymous tradition of Salty Sam is to teach Midshipman to bridle criticism in the ways of Sims humor, but to seek to inspire change and reform through the argument of the obvious.