Victory over Japan Day

| Victory over Japan Day | |

|---|---|

| Date | August 15 (UK), September 2 (US), September 3 (China) |

| Frequency | annual |

Victory over Japan Day (also known as Victory in the Pacific Day, V-J Day, or V-P Day) is the day on which Japan surrendered in World War II, in effect ending the war. The term has been applied to both of the days on which the initial announcement of Japan's surrender was made – to the afternoon of August 15, 1945, in Japan, and, because of time zone differences, to August 14, 1945 (when it was announced in the United States and the rest of the Americas and Eastern Pacific Islands) – as well as to September 2, 1945, when the signing of the surrender document occurred, officially ending World War II.

August 15 is the official V-J Day for the UK, while the official U.S. commemoration is September 2.[1] The name, V-J Day, had been selected by the Allies after they named V-E Day for the victory in Europe.

On September 2, 1945, a formal surrender ceremony was performed in Tokyo Bay, Japan, aboard the battleship USS Missouri. In Japan, August 15 usually is known as the "memorial day for the end of the war" (終戦記念日 Shūsen-kinenbi); the official name for the day, however, is "the day for mourning of war dead and praying for peace" (戦没者を追悼し平和を祈念する日 Senbotsusha o tsuitōshi heiwa o kinensuru hi). This official name was adopted in 1982 by an ordinance issued by the Japanese government.[2]

Surrender

Events before V-J Day

On 6 and 9 August 1945, the United States dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. On August 9, the Soviet Union declared war on Japan. The Japanese government on August 10 communicated its intention to surrender under the terms of the Potsdam Declaration, but with too many conditions for the offer to be acceptable to the Allies.

The news of the Japanese offer, however, was enough to begin early celebrations around the world. Allied soldiers in London danced in a conga line on Regent Street. Americans and Frenchmen in Paris paraded on the Champs-Elysées singing "Don't Fence Me In". American soldiers in Berlin shouted "It's over in the Pacific", and hoped that they would now not be transferred there to fight the Japanese. Germans stated that the Japanese were wise enough to—unlike themselves—give up in a hopeless situation, but were grateful that the atomic bomb was not ready in time to be used against them. Moscow newspapers briefly reported on the atomic bombings with no commentary of any kind. While "Russians and foreigners alike could hardly talk about anything else", the Soviet government refused to make any statements on the bombs' implication for politics or science.[3]

In Chungking, Chinese fired firecrackers and "almost buried [Americans] in gratitude". In Manila, residents sang "God Bless America". On Okinawa, six men were killed and dozens were wounded as American soldiers "took every weapon within reach and started firing into the sky" to celebrate; ships sounded general quarters and fired anti-aircraft guns as their crews believed that a Kamikaze attack was occurring. On Tinian island, B-29 crews preparing for their next mission over Japan were told that it was cancelled, but that they could not celebrate because it might be rescheduled.[3]

Japan's acceptance of the Potsdam Declaration

A little after noon Japan Standard Time on August 15, 1945, Emperor Hirohito's announcement of Japan's acceptance of the terms of the Potsdam Declaration was broadcast to the Japanese people over the radio. Earlier the same day, the Japanese government had broadcast an announcement over Radio Tokyo that "acceptance of the Potsdam Proclamation [would be] coming soon", and had advised the Allies of the surrender by sending a cable to U.S. President Harry S Truman via the Swiss diplomatic mission in Washington, D.C.[4] A nationwide broadcast by Truman was aired at seven o'clock p.m. (daylight time in Washington, D.C.) on August 14 announcing the communication and that the formal event was scheduled for September 2. In his announcement of Japan's surrender on August 14, Truman said that "the proclamation of V-J Day must wait upon the formal signing of the surrender terms by Japan".[5]

Since the European Axis Powers had surrendered three months earlier (V-E Day), V-J Day was the effective end of World War II, although a peace treaty between Japan and the United States was not signed until 1952, and between Japan and the Soviet Union in 1956. In Australia, the name V-P Day was used from the outset. The Canberra Times of August 14, 1945, refers to VP Day celebrations, and a public holiday for VP Day was gazetted by the government in that year according to the Australian War Memorial.[6][7]

Public celebrations

After news of the Japanese acceptance and before Truman's announcement, Americans began celebrating "as if joy had been rationed and saved up for the three years, eight months and seven days since Sunday, Dec. 7, 1941" (the day of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor), Life magazine reported.[8] In Washington, D.C. a crowd attempted to break into the White House grounds as they shouted "We want Harry!"[9][10]

In San Francisco two women jumped naked into a pond at the Civic Center to soldiers' cheers.[8] More seriously, thousands of drunken people, the vast majority of them Navy enlistees who had not served in the war theatre, embarked in what the San Francisco Chronicle summarized in 2015 as "a three-night orgy of vandalism, looting, assault, robbery, rape and murder" and "the deadliest riots in the city's history", with more than 1000 people injured, 13 killed, and at least six women raped. None of these acts resulted in serious criminal charges, and no civilian or military official was sanctioned, leading the Chronicle to conclude that "the city simply tried to pretend the riots never happened".[11]

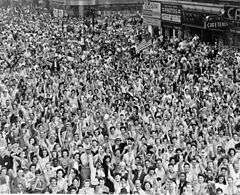

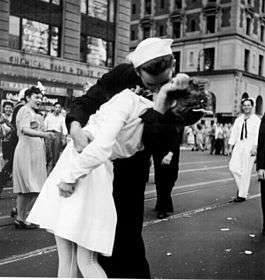

The largest crowd in the history of New York City's Times Square gathered to celebrate.[8] The victory itself was announced by a headline on the "zipper" news ticker at One Times Square, which read "*** OFFICIAL TRUMAN ANNOUNCES JAPANESE SURRENDER ***"; the six asterisks represented the branches of the U.S. Armed Forces.[12] In the Garment District, workers threw out cloth scraps and ticker tape, leaving a pile five inches deep on the streets. A "coast-to-coast frenzy of [servicemen] kissing" occurred, with Life publishing photographs of such kisses in Washington, Kansas City, Los Angeles, and Miami.[8]

Crowds celebrating V-J Day in Times Square

Crowds celebrating V-J Day in Times Square Citizens and workers of Oak Ridge, Tennessee celebrate V-J Day.[n 1]

Citizens and workers of Oak Ridge, Tennessee celebrate V-J Day.[n 1] Allied military personnel in Paris celebrating V-J Day

Allied military personnel in Paris celebrating V-J Day Crowds in Shanghai celebrating V-J Day

Crowds in Shanghai celebrating V-J Day Dancing Man in Sydney on 15 August 1945.

Dancing Man in Sydney on 15 August 1945.

Civilians and service personnel in London celebrating V-J Day on 15 August 1945.

Civilians and service personnel in London celebrating V-J Day on 15 August 1945.

Famous photographs

One of the best-known kisses that day appeared in V-J Day in Times Square, one of the most famous photographs ever published by Life. It was shot on August 14, 1945, shortly after the announcement by President Truman occurred and people began to gather in celebration. Alfred Eisenstaedt went to Times Square to take candid photographs and spotted a sailor who "grabbed something in white. And I stood there, and they kissed. And I snapped four times." [13] The same moment was captured in a very similar photograph by Navy photographer Victor Jorgensen (right), published in the New York Times.[14] Several people have since claimed to be the sailor and nurse.[15] It has since been established that the woman in the Alfred Eisenstaedt photograph was Greta Zimmer Friedman, and the sailor George Mendonça.

Another famous photograph is that of the Dancing Man in Elizabeth Street, Sydney, captured by a press photographer and a Movietone newsreel. The film and stills from it have taken on iconic status in Australian history and culture as a symbol of victory in the war.

Japanese reaction

_luisteren_de_Japanse_bevelhebber_kolonel_Kaida_Tatuichi_en_zijn_stafcommandant_majoor_Muiosu_Slioji_aan_dek_van_H_TMnr_10001519.jpg)

On August 15 and 16 some Japanese soldiers, devastated by the surrender, committed suicide. Well over 100 American prisoners of war were also murdered. In addition, many Australian and British prisoners of war were murdered in Borneo, at both Ranau and Sandakan, by the Imperial Japanese Army.[16] At Batu Lintang camp, also in Borneo, death orders were found which proposed the murder of some 2,000 POWs and civilian internees on September 15, 1945.[17]

Ceremony aboard the USS Missouri

The formal signing of the Japanese Instrument of Surrender took place on board the battleship USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay on September 2, 1945, and at that time Truman declared September 2 to be the official V-J Day.[18]

Chronology

- April 1 – June 21, 1945: Battle of Okinawa. 85,000+ US military casualties, and 140,000+ Japanese. Approximately one-fourth of the Okinawan civilian population died, often in mass suicides organized by the Imperial Japanese Army.

- July 26: Potsdam Declaration is issued. Truman tells Japan, "Surrender or suffer prompt and utter destruction."[19]

- July 29: Japan rejects the Potsdam Declaration.

- August 2: Potsdam conference ends.

- August 6: The US drops an atomic bomb, Little Boy, on Hiroshima. In a press release 16 hours later, Truman warns Japan to surrender or "...expect a rain of ruin from the air, the like of which has never been seen on this earth."[20]

- August 9: USSR declares war on Japan, and starts Operation August Storm. The US drops another atomic bomb, Fat Man, on Nagasaki.

- August 15: Japan surrenders. Date is described as "V-J Day" or "V-P Day" and such in newspapers in the United States, United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, and Canada.

- September 2: Official surrender ceremony; President Truman declares September 2 as the official "V-J Day".

- November 1: Scheduled commencement of Operation Olympic, the planned allied invasion of Kyushu.

- March 1, 1946: Scheduled commencement of Operation Coronet, the planned allied invasion of Honshu.

- September 8, 1951: 48 countries including Japan and most of the Allies sign the Treaty of San Francisco

- April 28, 1952: The Treaty of San Francisco goes into effect, formally ending the state of war between Japan and most of the Allied countries.

Post war:

- Some Japanese soldiers continued to fight on isolated Pacific islands until at least the 1970s, with the last known Japanese soldier surrendering in 1974.[21][22][23][24]

Commemoration

China

As the final official surrender of Japan was accepted aboard the battleship USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay on September 2, 1945, the Nationalist Government of the Republic of China, which represented China on the Missouri, announced three-day holidays to celebrate V-J Day, starting September 3. Starting from 1946, September 3 was celebrated as "Victory of War of Resistance against Japan Day" (Chinese: 抗日戰爭勝利紀念日; pinyin: Kàngrì Zhànzhēng Shènglì Jìniànrì), which evolved into the Armed Forces Day (Chinese: 軍人節) in 1955. September 3 is recognized as V-J Day in mainland China.[25]

Hong Kong

Hong Kong was handed over by the Imperial Japanese Army to the Royal Navy on August 30, 1945, and resumed its pre-war status as a British dependency. Hong Kong celebrated the "Liberation Day" (Chinese: 重光紀念日; Jyutping: cung4 gwong1 gei2 nim3 jat6) on August 30 (later moved to the Saturday preceding the last Monday in August) annually, which was a public holiday before 1997. After the transfer of sovereignty in 1997, the celebration was moved to the third Monday in August and renamed "Sino-Japanese War Victory Day", the Chinese name of which is literally "Victory of War of Resistance against Japan Day" as in the rest of China, but this day was removed from the list of public holidays in 1999. In 2014, the Chief Executive's Office announced that a commemoration ceremony would be held on 3 September, in line with the "Victory Day of the Chinese people's war of resistance against Japanese aggression" in Mainland China.[26]

Recently a bill has been passed in the Hong Kong Legislative council to designate September 3, 2015 (Thursday) on a one-off basis as an additional General Holiday (GH) and Statutory Holiday (SH). A government spokesman said, "70th anniversary day of the victory of the Chinese people's war of resistance against Japanese aggression".

Korea

Gwangbokjeol, (meaning "the day the light returned") celebrated annually on August 15, is one of the Public holidays in South Korea. It commemorates Victory over Japan Day, which liberated Korea from Japanese rule. The day is also celebrated as a public holiday, Liberation Day, in North Korea, and is the only public holiday celebrated in both Koreas.

The Netherlands

The Netherlands has one national and several regional or local remembrance services on or near to the 15th of August. The national service is at the "Indisch monument" (Dutch for "Indies Monument") in The Hague, where the Dutch victims of the Japanese occupation of the Dutch East Indies are remembered, usually in the presence of the head of state and the government. In total, there are about 20 services, also in the Indies remembrance center in Bronbeek in Arnhem. The Japanese occupation meant the twilight of Dutch colonial rule over Indonesia. Indonesia declared itself independent on 17 August 1945, just two days after the Japanese surrendered. The Indonesian war of independence lasted until 1948, with the Netherlands recognizing Indonesian sovereignty in late December of that year.

Vietnam

On the day of surrender of Japan, Hồ Chí Minh declared an independent Democratic Republic of Vietnam.

United States

Although September 2 is the designated V-J Day in the entire United States, the event is recognized as an official holiday only in the U.S. state of Rhode Island, where the holiday's official name is "Victory Day",[27] and it is observed on the second Monday of August. There were several attempts in the 1980s and 1990s to eliminate or rename the holiday on the grounds that it is discriminatory. While those all failed, the Rhode Island General Assembly did pass a resolution in 1990 "stating that Victory Day is not a day to express satisfaction in the destruction and death caused by nuclear bombs at Hiroshima and Nagasaki."[28] It is instead commemorative of those who fought, as Rhode Island sent a significantly above-average percentage of its population into the Pacific theater.

Australia

In Australia, some people use the term VP Day in preference to "VJ Day", but in the publication The Sixth Year of War in Pictures published by the Melbourne Herald-Sun in 1946, the term VJ Day is used on pages 250 and 251.[29] Also an Australian Government 50th Anniversary Medal issued in 1995 has VJ-Day stamped on it.[30]

Amateur radio

Amateur radio operators in Australia hold the "Remembrance Day Contest" on the weekend nearest VP Day, August 15, remembering amateur radio operators who died during World War II and to encourage friendly participation and help improve the operating skills of participants. The contest runs for 24 hours, from 0800 UTC on the Saturday, preceded by a broadcast including a speech by a dignitary or notable Australian (such as the Prime Minister of Australia, Governor-General of Australia, or a military leader) and the reading of the names of amateur radio operators who are known to have died. It is organized by the Wireless Institute of Australia, with operators in each Australian state contacting operators in other states, New Zealand, and Papua New Guinea. A trophy is awarded to the state that can boast the greatest rate of participation, based on a formula including: number of operators, number of contacts made, and radio frequency bands used.[31]

World Peace Day

It was suggested in the 1960s to declare September 2, the anniversary of the end of World War II, as an international holiday to be called World Peace Day. However, when this holiday came to be first celebrated beginning in 1981, it was designated as September 21, the day the General Assembly of the United Nations begins its deliberations each year.

See also

- End of World War II in Asia

- Gwangbokjeol, celebrating the end of Japanese rule in Korea

- Kyūjō Incident

- Victory in Europe Day

- Victory Day (United States)

- Stunde Null

Notes

- ↑ Oak Ridge was part of the Manhattan Project, which resulted in the atomic bomb.

References

- ↑ "History.com". Retrieved 2010-08-14.

- ↑ 厚生労働省:全国戦没者追悼式について (in Japanese). Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. 2007-08-08. Retrieved 2008-02-16.

- 1 2 "Victory Reports Around the World: U. S. Fighting Men Lead Wild Celebrations at Japs' Surrender Offer". Life. 1945-08-20. pp. 38–38A. Retrieved November 25, 2011.

- ↑ Hakim, Joy (1995). A History of Us: War, Peace and all that Jazz. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-509514-6.

- ↑ "JAPANESE ACCEPTANCE OF POTSDAM DECLARATION ANNOUNCED BY PRESIDENT TRUMAN". ibiblio.org.

- ↑ "Canberra Times - Local Canberra News, World News & Breaking News in ACT, Australia". Retrieved August 15, 2016.

- ↑ Australian War Memorial

- 1 2 3 4 "Victory Celebrations". Life. 1945-08-27. p. 21. Retrieved November 25, 2011.

- ↑ "Scenes of Rejoicing in Washington and New York". The Times Recorder. Zanesville, OH. August 14, 1945. Retrieved August 20, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "World Enters Era of Peace as Truman Warns of Task Ahead". Warren Times Mirror. Warren, PA. August 15, 1945. p. 1. Retrieved August 20, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Kamiya, Gary (August 14, 2015). "'Peace Riots' left trail of death at end of WWII in S.F.". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved August 14, 2015.

- ↑ Van Gelder, Lawrence (December 11, 1994). "Lights Out for Times Square News Sign?". The New York Times. Retrieved 20 January 2013.

- ↑ Eisenstaedt, Alfred (1985). Eisenstaedt on Eisenstaedt. Abbeville Press.

- ↑ Newman, Andy (August 13, 2010). "Nurse Tells of Storied Kiss. No, Not That Nurse.". The New York Times. New York, NY. Retrieved August 24, 2015.

- ↑ Chan, Sewell (August 14, 2007). "62 Years Later, a Kiss That Can't Be Forgotten". The New York Times. New York, NY. Retrieved August 24, 2015.

- ↑ Remembering Sandakan: 1945–1999 Archived July 14, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. "Captain Hoshijima Susumi was able to reveal from his knowledge of the war crimes interrogation documents that the last POWs had been killed at Ranau on 27 August 1945, well after the Japanese surrender. They had undoubtedly been killed, in Moffitt's view, to stop them being able to testify to the atrocities committed by the guards."

- ↑ Ooi, Keat Gin (1998) Japanese Empire in the Tropics: Selected Documents and Reports of the Japanese Period in Sarawak, Northwest Borneo, 1941–1945 Ohio University Centre for International Studies, Monographs in International Studies, SE Asia Series 101 (2 vols), page 648; Keith, Agnes, 1947 Three Came Home183, 206

- ↑ "Public Papers". Truman Library. 1945-09-01. Retrieved 2012-02-28.

- ↑ "Potsdam Declaration: Proclamation Defining Terms for Japanese Surrender Issued, at Potsdam, July 26, 1945". National Science Digital Library.

- ↑ "PBS: Statement By The President". Retrieved August 15, 2015.

- ↑ Kristof, Nicholas D. "Shoichi Yokoi, 82, Is Dead; Japan Soldier Hid 27 Years," New York Times. September 26, 1997.

- ↑ "The Last PCS for Lieutenant Onoda," Pacific Stars and Stripes, March 13, 1974, p6

- ↑ "Onoda Home; 'It Was 30 Years on Duty'," Pacific Stars and Stripes, March 14, 1974, p7

- ↑ "The Last Last Soldier?". Time.com. 1975-01-13. Retrieved 2012-02-28.

- ↑ V-J Day in the People's Republic of China (Baidu Encyclopedia) in Chinese

- ↑ "HK to mark China 'victory' over Japan". bangkokpost.com.

- ↑ "Home > State Library > History of Rhode Island > State Facts & Figures". Rhode Island Office of the Secretary of State. Retrieved 2013-09-24.

- ↑ "R.I. Last State Still Marking V-J Day".

- ↑ "The Sixth Year of War in Pictures", The Sun News Pictorial, Melbourne. 1946

- ↑ "Wartime Issue 21 - Australian War Memorial". Retrieved August 15, 2016.

- ↑ "Remembrance Day Contest". Retrieved 2009-08-15.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to V-J Day. |

- Original Document: Surrender of Japan

- The U.S. Army in Post-WWII Japan

- V-J Day portal at the US Army Center of Military History

- VJ Day in New Zealand