Villmar

| Villmar | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

Villmar | ||

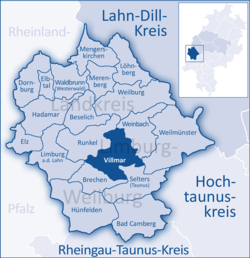

Location of Villmar within Limburg-Weilburg district  | ||

| Coordinates: 50°23′29″N 8°11′31″E / 50.39139°N 8.19194°ECoordinates: 50°23′29″N 8°11′31″E / 50.39139°N 8.19194°E | ||

| Country | Germany | |

| State | Hesse | |

| Admin. region | Gießen | |

| District | Limburg-Weilburg | |

| Government | ||

| • Mayor | Hermann Hepp (CDU) | |

| Area | ||

| • Total | 43.1 km2 (16.6 sq mi) | |

| Population (2015-12-31)[1] | ||

| • Total | 6,857 | |

| • Density | 160/km2 (410/sq mi) | |

| Time zone | CET/CEST (UTC+1/+2) | |

| Postal codes | 65606 | |

| Dialling codes | 06482, 06483, 06474 | |

| Vehicle registration | LM | |

| Website | www.villmar.de | |

Villmar is a market village in the Limburg-Weilburg district in Hesse, Germany. The community is the centre for quarrying and processing the so-called Lahn Marble.

Geography

Location

Villmar lies in the Lahn River valley between the Westerwald and the Taunus, some ten kilometres east of Limburg. In terms of the natural environment, the southwestern part of the municipal area comprises the eastern part of the Limburg Basin (Limburger Becken, this part known locally as the Villmarer Bucht), a nearly even two- to three-kilometre-wide plain that opens to the west lying at elevations of 160 to 180 m into which the Lahn’s winding lower valley has cut a channel about 50 metres deep.

Conditioned by the mild climate and the extensive loess soils, intensive crop production prevails here. To the north, the somewhat higher (220–260 m), more richly wooded Weilburger Lahntalgebiet ("Weilburg Lahn valley area") joins up with the Weilburger Lahntal ("Weilburg Lahn valley") and the Gaudernbacher Platte ("Gaudernbach Tableland"), where cropland is limited to scattered loess islands. In the southeast rises the likewise more thickly wooded northwestern part of the Eastern Hintertaunus (or Langhecker Lahntaunus) with the Villmarer Galgenberg (277 m) as its westernmost outpost, visible from a great distance. The municipal area's highest point (332 m) is found southeast of the outlying centre of Langhecke, and the lowest point (114 m) is on the community's western limit where the Lahn flows into the town of Runkel.

Geology

Lying in the geologically significant Lahnmulde ("Lahn Hollow"), Villmar is rich in mineral deposits from the Middle Devonian period: silver, iron ore, slate, and limestone. As the reef limestone (called Lahn marble) could be cut and polished, it was of economic importance to the area. In addition to the reef limestone, the extensively mined, mostly greenish diabase tuff was used for many purposes (for instance, ringwall, parish house and most older buildings' cellars.)

The later deposits from the Tertiary, however, are of lesser importance. Small amounts of sand and gravel are quarried near the Villmarer Galgenberg. Tertiary vulcanism left behind sporadic basalt deposits near Falkenbach, Seelbach and Weyer. These deposits are no longer worked.

Neighbouring communities

Villmar borders in the northwest on the town of Runkel, in the northeast on the community of Weinbach, in the east on the community of Weilmünster, in the south on the communities of Selters and Brechen, and in the west on the town of Limburg (all in Limburg-Weilburg).

Constituent communities

Villmar’s Ortsteile are Aumenau, Falkenbach, Langhecke, Seelbach, Villmar and Weyer.

History

Villmar's main centre had its first documentary mention in 1053 when Emperor Heinrich III donated the royal estate of Villmar to the Benedictine Abbey of Saint Matthew in Trier. The landholding bound to this and the abbey's earnings was more closely circumscribed in later confirmations. Of particular importance in this is the abbot's right, already falsely appended to the donation document, to employ a secular Schutzvogt, which amounted to a noble title. In 1154, the abbey's ownership rights were assigned by Archbishop Hillin of Trier to the Villmar Church. A list was drawn up of places owing tithes, among them the current constituent communities of Seelbach, Aumenau and Weyer.

It is believed that in the same year, a falsification of the original document, backdated to 1054, appeared, which dealt with the Vogt rights as well as the parish’s extent, and thereby with tithes. The centres of Aumenau and Weyer were already being mentioned in writing in the 8th century, and Falkenbach and Langhecke followed in the 13th and 14th, respectively. Scholars have concluded, indirectly from other documents, that an autonomous parish of Villmar must already have arisen by 910. Even the placename “Villmar” suggests that the community had its beginnings before Frankish times.

In 1166 a Trier ministerial family named “von Villmar”, who had apparently moved to the community not long before this, was living here. The name “von Koblenz” for this family also crops up later, although by the late 13th century, the former seems to have definitively become the family’s name. Their coat of arms was quartered in gules (red) and argent (silver or white). In the 14th century, a side-branch of the family formed in Hadamar. There is evidence that the family’s holdings lay around Limburg, Montabaur and Delkenheim Castle in the Rheingau, and in the Wetterau. In 1428, the family died out.

Acting as Vögte (plural of Vogt) beginning in the 13th century were counts from the House of Isenburg, in whose service also stood the House of Villmar. In the 15th and 16th centuries, the House of Solms also had Vogt rights. The Landeshoheit (roughly, “territorial sovereignty”) over Villmar’s municipal area, to which today’s constituent community of Arfurt also belonged, was contested in later times by the Gaugrafen (“Regional Counts”) of Diez, and later, as their successors in the tithing area (Cent) of Aumenau after 1366, by the Counts of Wied-Runkel. As of the 13th century, the historical record also shows Trier’s ambition to wrest ascendancy over Villmar from the local overlords.

In 1346, in a move instigated by Archbishop Balduin of Luxembourg, Villmar was granted town rights in the Archbishop’s hopes that this might further his goal of annexing the town. In the end, though, this ambition never came to fruition, as a basis for this deed in law could not be established. Trier did not succeed in conquering Villmar in 1359 despite the would-be conquerors’ attack of the fortifications. The conflict with the Villmar Vögte reached its high point in 1360 when the Trier coadjutor bishop Kuno von Falkenstein destroyed the Burg Gretenstein (castle), built near Villmar by Philipp von Isenburg.

The dispute over the territory’s overlordship was settled in the 16th century when, with Saint Matthew’s Abbey’s (Abtei St. Matthias) consent in 1565, the Villmar Vogt rights held by the Isenburg-Büdingens and the Solms-Münzenbergs were sold to the Electorate of Trier for 14,000 Frankfurt guilders. In 1596, the area was united with Wied-Runkel, which forwent Ascendancy over the Villmar-Arfurt municipal area. It was made into a Trier bailiwick. This also had consequences for religious affiliation: while Villmar (and Arfurt) remained uninfluenced by the Reformation, the centres of Seelbach, Falkenbach, Aumenau and Weyer in the Runkel domain were converted, first in 1562 to Lutheranism, and as of 1587 and 1588 to Calvinism. Despite the Reformation, the Abbey continued to derive income as the landlord, including church tithes, until 1803.

After the Electorate’s and the Holy Roman Empire’s fall between 1803 and 1806, Villmar passed in 1806 to the newly created Duchy of Nassau. In 1866 it was annexed by Prussia. After the Second World War, Villmar became part of the new state (Bundesland) of Hesse.

Within the framework of municipal reform in Hesse, the above-named constituent communities (all former self-administering communities in the old Oberlahnkreis district) merged in 1970 and 1971 to form the new collective community of Villmar. Since 2002 it has been designated a Marktflecken (“market town”).

Politics

Community council

The municipal election held on 26 March 2006 yielded the following results:

| Parties and Voter Communities | % 2006 |

Seats 2006 |

% 2001 |

Seats 2001 | |

| CDU | Christian Democratic Union of Germany | 42.9 | 13 | 41.4 | 13 |

| SPD | Social Democratic Party of Germany | 41.8 | 13 | 45.9 | 14 |

| FDP | Free Democratic Party | 2.2 | 1 | – | – |

| FWG | Freie Wählergemeinschaft Gesamtgemeinde Villmar | 7.7 | 2 | 7.8 | 2 |

| AAV | Aktive Alternative Villmar | 5.5 | 2 | 4.9 | 2 |

| Total | 100.0 | 31 | 100.0 | 31 | |

| Voter turnout in % | 53.7 | 58.8 | |||

Sightseeing

St. Peter’s and Paul’s Parish Church

The church was built between 1746 and 1749 by Thomas Neurohr (Boppard) on the former site of a 1282 Late Romanesque church which had been called a “basilica”. It was built with a five-arched nave with buttresses and flat groin vaulting. The somewhat narrower quire with its arch and 5/8 end is set to the east, ahead of the tower. The latter was given a new neo-Gothic pinnacle after a lightning strike in 1885.

Inside is found rich Late Baroque décor (1760–64) from the Hadamar school (Johann Thüringer, Jakob Wies) as well as works made in the 18th and 19th centuries from local Lahn marble. The Jakobusaltar, nowadays in the Baroque style, was mentioned as early as 1491 as the Jakobus- und Matthias-Altar.[2]

In 1957 architect Paul Johannbroer (Wiesbaden) designed an expansion similar to a quire towards the west. A Celebration altar and an ambo made of French lime sand brick were carved by sculptor Walter Schmitt (Villmar) in the 1980s and 1990s. The organ was built in 1754 and 1755 by Johann Christian Köhler (Frankfurt). After several overhauls (1885/86 Gebr. Keller, Limburg, 1932 and 1976 Johannes Klais, Bonn), today it comprises 27 stops on two keyboards and one pedalboard. Its Baroque design has been preserved.

Lahn marble

The Lahn Marbles are a group of reef limestones with about 100 varieties of dimension stones.[3]

- The Marmorbrücke (Marble Bridge) across the Lahn River was built 1894/95. The span is supported by two piers surmounted by three segmental arches; its length to the abutments is 21.5 m. The piers and arches are made out of massive Lahn marble blocks, and the sides are dressed with decorative Lahn marble stones of various kinds. This bridge, an outstanding example of its kind in Germany, has been protected as a Technical Monument since 1985.

- The Unica-Bruch, an abandoned Lahn marble quarry, holds the centre of a 380-million-year-old fossil coral reef (limestone) from the Middle Devonian.

- The Lahnmarmor-Museum, opened in 2004, shows how Lahn marble came into being, was quarried, and was used.

- At the Museum Wiesbaden, many exhibits about Lahn marble are displayed. Moreover, many buildings in Wiesbaden are dressed with the stone.

- The Villmarer Lahnmarmor-Weg offers a glimpse into how the varieties of marble were quarried and processed.

- The marble from Villmar was used in building, among other structures, the Empire State Building in New York City, United States.

Other landmarks

- King Konrad Memorial. In 1894, a statue of King Conrad I of Germany (911-918) was erected on the Bodensteiner Lay, a cliff downstream towards Runkel on the Lahn’s left bank. It was made of Devonian limestone.

- Fortification remains: A circular rampart was recorded in 1250 and girded the community until the early 19th century. Originally it had three crenellated gates and seven towers. Now all that remains is the bottom part of the Mattheiser Turm (Matthews' Tower) and a few wall remnants, mostly in the former Kellerei-Bezirk (wine cellar quarter). There are two well-preserved gateway arches (Matthiaspforte and Valeriuspforte). The Vogteiburg (“sheriff’s castle”) from the 13th century, built as a residential tower, can be discerned through the remains of its lower walls. The Vögte held authority over the high court, which was sited on the Dingplatz, between the castle and the church. In the 18th century this was called the alter Burg Platz. Today it is a former graveyard. The execution site lay roughly 2 km southeast of town on Galgenberg (Gallows Mountain). In 1890 the diocesan building master Max Meckel replaced the wine-cellar building with a new parish house built in English neo-Gothic style. He incorporated a tower from the old building.

- NaturFreundehaus “Wilhelmsmühle” or Lahntalhaus, between Villmar and Aumenau, used since 1928; a new building was constructed in 1932. Many prominent politicians and like-minded people came here for relaxation and quiet. Among them were the Social Democrat Philipp Scheidemann, who after the First World War had proclaimed the First German Republic in Berlin in 1918; the longtime SPD chairman Erich Ollenhauer; and the former Mayor (Oberbürgermeister) of the state capital Wiesbaden, Georg Buch. For a time he acted as President of the Hesse Landtag. Unique among the events at the Lahntalhaus before the Second World War were the Kinderrepubliken (Children’s Republics). Several hundred participants would stay at the tent camp, which bore the motto Ordnung, Freundschaft, Solidarität (Order, Friendship, Solidarity).

Economy and infrastructure

Villmar’s economic importance lay in marble processing, which began in the 17th century. From 1790 onwards, twelve quarries are known to have been worked, with others in the outlying area. In the second half of the 20th century, Lahn marble came up against competition from cheaper imports, disrupting mining operations. Processing continued, however, even as smaller works disappeared over time, often owing to lack of growth. Among the greater operations, the Nassauische Marmorwerke closed its gates in 1979 after becoming insolvent. Likewise, the Steinverarbeitungsbetrieb Engelbert Müller, which had been known since the War for great building projects of sacred objects, shut down in 2001. The last quarrying in Villmar was done in 1989 for the reconstruction of the high altar at the Jesuitenkirche Mannheim, which had been heavily damaged in the Second World War. Four stoneworking businesses are still running in town today.

In the 17th century, silver was mined, although the lode was soon exhausted.

Since the 1950s, Villmar has changed into a residential community with moderate tourism. The great majority of workers earns its livelihood in Limburg an der Lahn, Wetzlar, Gießen and, given the favourable transport connections, the Frankfurt Rhine Main Region.

Transport

Villmar is linked to the long-distance road network by the Limburg-Süd Autobahn interchange on the A 3 (Cologne–Frankfurt), 10 km away.

Within the community lie Villmar and Aumenau railway stations on the Lahn Valley Railway, serving Koblenz, Limburg, Villmar, Wetzlar and Gießen. Regionalbahn trains stop here, running the DB Regio AG Limburg–Gießen service. The nearest InterCityExpress stop is the railway station at Limburg Süd on the Cologne-Frankfurt high-speed rail line.

Villmar’s main centre and outlying centres of Aumenau and Falkenbach abut the Lahn, which is not only a river, but also a federal waterway. Along the Lahn also runs the heavily used R7 bicycle path.

Education

Villmar is home to the Johann-Christian-Senckenberg-Schule, a primary school, Hauptschule and Realschule all in one, as well as to a primary school in the outlying centre of Aumenau. Higher schools are to be found in Limburg, Weilburg and Weilmünster.

Institutions

- Gemeindliche Kindertagesstätte Villmar (municipal daycare)

- Gemeindliche Kindertagesstätte Aumenau (municipal daycare)

- Gemeindlicher Kindergarten Seelbach (municipal kindergarten)

- Gemeindlicher Kindergarten Weyer (municipal kindergarten)

- Katholischer Kindergarten Villmar (Catholic kindergarten)

- Villmar Volunteer Fire Brigade, founded in 1929 (includes youth fire brigade)

- Aumenau Volunteer Fire Brigade, founded in 1932 (includes youth fire brigade)

- Falkenbach Volunteer Fire Brigade, founded in 1934 (includes youth fire brigade)

- Langhecke Volunteer Fire Brigade, founded in 1934 (includes youth fire brigade)

- Seelbach Volunteer Fire Brigade, founded in 1932 (includes youth fire brigade)

- Weyer Volunteer Fire Brigade, founded in 1933 (includes youth fire brigade since 1983)

Famous people

Sons and daughters of the town

- Willy Bokler (b.1 September 1909 in Villmar; d. 12 February 1974), Prelate and Federal President of the Bund der deutschen katholischen Jugend (BDKJ, “Federation of German Catholic Youth) 1952-1965

- Bernhard Falk (b. 5 August 1948 in Villmar), Vice-president of the Bundeskriminalamt

- Prof. Dr. Dr. habil. Ernst O. Göbel (b. 24 March 1946 in Seelbach), President of the Physikalisch-Technische Bundesanstalt

Honorary citizens

- Dr. Jakob Hartmann (b. 22 February 1879; d. 7 May 1961), Physician in Villmar 1905-1956

- Nikolaus Homm (b. 6 May 1909; d. 22 October 2004), Catholic priest in Villmar 1952-1976

- Peter Weyand (b.16 May 1875; d. 4 February 1963), Catholic priest in Villmar 1924-1952

Famous people who have worked in town

- Heinrich Joseph Rompel (b. 1746), Cubist from Mainz in 1792/93, was among the leaders in the "Mainz Revolution".

- Hubert Aumüller (b. 26 October 1927), Former mayor of the greater community of Villmar. He was elected mayor of Villmar on 31 May 1952. After 36 years in office, he retired on 30 June 1988. He was formerly the youngest, and by years of service, the oldest mayor in Hesse. His service was recognized with a series of honours, among them the Bundesverdienstkreuz (1982) and, on the occasion of his retirement, the Freiherr-vom-Stein-Plakette.

- Bernhard Hemmerle (b. 25 December 1949), Church music director, cantor in Villmar 1975-1994.

- Paul Theodor Lüngen (b. 29 June 1912; d. 17 February 1997), Army music master, retired; founder of the Villmar Volunteer Fire Brigade’s wind orchestra, leader from December 1979 - August 1985.

References

- ↑ "Bevölkerung der hessischen Gemeinden". Hessisches Statistisches Landesamt (in German). August 2016.

- ↑ Jakobus- und Matthiasaltar. In: Germania Sacra, NF 34: Die Bistümer der Kirchenprovinz Trier. Das Erzbistum Trier 8. Die Benediktinerabtei St. Eucharius - St. Matthias vor Trier. Bearb. von Petrus Becker. 1996. p. 575, ISBN 3-11-015023-9 Digitalisat

- ↑ Thomas Kirnbauer: Nassau Marble or Lahn Marble - a famous Devonian dimension stone from Germany. In: SDGG, Schriftenreihe der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Geowissenschaften, Vol. 59, 2008

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Villmar. |

- Community’s homepage (German)

- Heimatforschung Villmar (German)

- Lahnmarmor-Museum (German)

- Villmar at DMOZ