We Were Strangers

| We Were Strangers | |

|---|---|

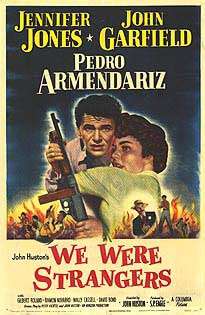

Theatrical poster | |

| Directed by | John Huston |

| Produced by | Sam Spiegel |

| Written by |

John Huston Peter Viertel |

| Based on |

China Valdez 1948 novel Rough Sketch by Robert Sylvester |

| Starring |

Jennifer Jones John Garfield Pedro Armendáriz Gilbert Roland |

| Music by | George Antheil |

| Cinematography | Russell Metty |

| Edited by | Al Clark |

| Distributed by |

Columbia Pictures Horizon Pictures |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 106 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

We Were Strangers is a 1949 adventure–drama film directed by John Huston and starring Jennifer Jones and John Garfield. Set in 1933, the film concerns a group of revolutionaries attempting to overthrow the Cuban government of Gerardo Machado. The story is based loosely on an episode in Robert Sylvester's novel Rough Sketch and draws on historical events.

Plot

The story draws on events that occurred as part of the political violence that led to the overthrow of Cuban dictator Gerardo Machado y Morales in 1933. In 1932, a violent opposition group, the ABC (abecedarios), assassinated the President of the Cuban Senate Clemente Vazquez Bello. They had constructed a tunnel to reach the Vazquez family crypt in Havana's Colón Cemetery and planted an explosive device there, anticipating that Machado would attend the funeral. The plan failed when the family decided to bury Vazquez elsewhere.[1]

The film is about a group of revolutionaries who plot to bring down their corrupt government. The title, chosen by the distributor Columbia Pictures in place of Rough Sketch, identifies how they come together with no prior associations, sharing only their political principles. China Valdez (Jennifer Jones) is a bank clerk who has a brother who distributes anti-government flyers. She watches as a government operative guns him down on the steps of the University of Havana. She vows to kill his assassin, Ariete. At her brother's funeral, Tony Fenner (John Garfield), an American confederate of her brother, tells her to join his anti-government underground group instead of taking revenge on her own. When he learns that China's house borders a cemetery, he devised a scheme to dig a tunnel from China's house to the cemetery, assassinate a senior government official whose family plot is in that cemetery, and then detonate a bomb during the man's funeral, killing the government officials among the mourners. His disparate group of tunnelers includes a dockworkers, a bicycle mechanic, and a graduate student. Much of the movie is devoted to the digging of the tunnel. The tunnelers struggle with the need to kill men who are less than entirely evil and to take the lives of innocent bystanders. Ramon goes mad thinking of these issues, wanders off and dies in a traffic accident. Ariete harasses China, jealous of her relationship with Fenner, who he has learned is actually Cuban by birth.

When the tunnel is ready, a prominent government minister is assassinated as planned. As a munitions expert prepares to set the bomb in place, they learn that the burial will take place elsewhere, not in the family tomb as expected. They make plans for Fenner, who by now is well known to Ariete, to leave Cuba. China will get the necessary funds from Fenner's account at her bank. Fenner rages about his failure, the disgrace of returning to the people who funded his trip with small donations, fleeing as he had as a boy with his father. Only in supporting him at this point does China declare her love for him. China obtains the funds but sends a fellow employee because she is being tailed by one of Ariete's men. But Fenner, unwilling to leave without her, comes to China's house. The film climaxes with a violent shoot-out sequence, followed by the outbreak of revolution and popular celebration.

Cast

- Jennifer Jones as China Valdés

- John Garfield as Tony Fenner

- Pedro Armendáriz as Armando Ariete

- Gilbert Roland as Guillermo Montilla

- Ramon Novarro as Chief

- Wally Cassell as Miguel

- Tito Renaldo as Manolo Valdés

- David Bond as Ramón Sánchez

- José Pérez as Toto

- Morris Ankrum as Mr. Seymour, bank manager

Production

Huston, recognizing the sensitive nature of the film's politics, formed an independent production company, Horizon Films, to finance the film.[2] One critic has noted the film is "a barely disguised indictment of U.S. foreign policy" as well as a study of "the poetry of failure" typical of Huston's style.[3] Huston cast Garfield partly because they shared the same political outlook.[3]

Much of the script was written as filming progressed. According to Peter Viertel, "Huston was going through a lot of personal problems at the time, and he was unable to concentrate on the film" even though it presented serious challenges: "It was a very difficult story with an ending that wasn't exactly considered happy by Hollywood standards." The ending was repeatedly rewritten by a variety of writers, with the final version by Ben Hecht.[4]

The supporting players include Mexican film star Pedro Armendáriz as the corrupt police chief, and former silent stars Gilbert Roland and Ramon Novarro as members of the resistance. John Huston makes a cameo appearance as a bank teller. Many of the film's outdoor scenes were shot against rear projections, which are quite noticeable, including views of Havana Harbor, Havana University, Morro Castle, and Colon Cemetery. The film, however, achieves an almost documentary-like feel with its stark black-and-white photography. The film was evidently unavailable for viewing until it was made available for domestic video sale in 2005, long after John Huston's other films became available.

During filming, Huston was asked to give Marilyn Monroe, then unknown, a screen test. As a result he cast her in a small role in his next film, The Asphalt Jungle.[4]

The musical score is noticeably restrained for the period, just a guitar in the background or one of the revolutionaries playing a calypso tune on the guitar, inventing lyrics as he sings.[5]

Reception

John Huston directed the film between two box office successes: Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948) and The Asphalt Jungle (1950). We Were Strangers was released in April 1949 and received mixed reviews. In the New York Times, Bosley Crowther praised the physical and psychological realism of the conspirators, but he disliked Jennifer Jones' performance and missed a central romance: "the real emotional tinder which is scattered within this episode is never swept into a pyramid and touched off with a quick, explosive spark".[6] Reviews in Time and Collier's were more positive, but the Hollywood Reporter denounced its politics: "a shameful handbook of Marxian dialectics ... the heaviest dish of Red theory ever served to an audience outside the Soviet".[7] The film was withdrawn from theaters shortly after its release.[5] The Communist Party's Daily Worker thought it was "capitalist propaganda.[3][2]

American audiences were perplexed by it, its largely Hispanic cast did not resonate with white Americans, and its shocking presidential assassination theme may have offended some sensibilities.[3]

Claimed effect on Lee Harvey Oswald

According to a biography of Lee Harvey Oswald and his wife, Oswald was "greatly excited" while watching We Were Strangers on television in October 1963, just a few weeks before he assassinated President John F. Kennedy.[8]

References

- ↑ Estrada, Alfredo José (2007). Havana: An Autobiography. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 174. ISBN 1-4039-7509-4.

- 1 2 Auerbach, Janathan (2011). Dark Borders: Film Noir and American Citizenship. Duke University Press. pp. 120–1. Retrieved January 21, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 Miller, Frank. "We Were Strangers (1949)". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved January 21, 2016.

- 1 2 Nott, Robert (2003). He Ran All the Way: The Life of John Garfield. New York: Limelight Editions. pp. 235–6. Retrieved January 21, 2016.

- 1 2 Madsen, Axel (1978). John Huston: A Biography. Doubleday. pp. 96ff. Retrieved January 21, 2016.

- ↑ Crowther, Bosley (April 28, 1949). "We Were Strangers (1949)". New York Times. Retrieved January 21, 2016.

- ↑ Gosse, Van (1993). Where the Boys are: Cuba, Cold War America and the Making of a New Left. London: Verso. pp. 42–3. Retrieved January 21, 2016.

- ↑ McMillan, Priscilla Johnson (1977). Marina and Lee: The Tormented Love and Fatal Obsession Behind Lee Harvey Oswald's Assassination of John F. Kennedy. Harpercollins. p. 474. ISBN 978-0060129538.

External links

- We Were Strangers at the Internet Movie Database

- We Were Strangers at AllMovie

- We Were Strangers at the TCM Movie Database

- We Were Strangers at the American Film Institute Catalog

- We Were Strangers at Rotten Tomatoes