Wide-field multiphoton microscopy

Wide-field multiphoton microscopy[2][3][4][5] refers to an optical non-linear imaging technique tailored for ultrafast imaging in which a large area of the object is illuminated and imaged without the need for scanning. High intensities are required to induce non-linear optical processes such as two-photon fluorescence or second harmonic generation. In scanning multiphoton microscopes the high intensities are achieved by tightly focusing the light, and the image is obtained by stage- or beam-scanning the sample. In wide-field multiphoton microscopy the high intensities are best achieved using an optically amplified pulsed laser source to attain a large field of view (~100 µm).[2][3][4] The image in this case is obtained as a single frame with a CCD without the need of scanning, making the technique particularly useful to visualize dynamic processes simultaneously across the object of interest. With wide-field multiphoton microscopy the frame rate can be increased up to a 1000-fold compared to multiphoton scanning microscopy.[3]

Introduction

The main characteristic of the technique is the illumination of a wide area on the sample with a pulsed laser beam. In nonlinear optics the amount of nonlinear photons (N) generated by a pulsed beam per (illuminating) area per second is proportional to[6][7]

,

where E is the energy of the beam in Joules, τ is the duration of the pulse in seconds, A is the illuminating area in square meters, and f is the repetition rate of the pulsed beam in Hertz. Increasing the illumination area thus reduces the amount of generated nonlinear photons unless the energy is increased. Optical damage does not depend on the energy delivered; It depends on the energy density, i.e. peak intensity Ip=E/(τA). Therefore, both the area and energy can be easily increased without the risk of optical damage if the peak intensity is kept low, and yet a gain in the amount of generated nonlinear photons can be obtained because of the quadratic dependence. For example, increasing both the area and energy 1000 fold, leaves the peak intensity unchanged but increases the generated nonlinear photons by 1000 fold. This 1000 extra photons are indeed generated over a larger area. In imaging this means that the extra 1000 photons are spread over the image, which at first might not seem an advantage over multiphoton scanning microscopy. The advantage however becomes evident when the size of the image and the scanning time are considered.[3] The amount of nonlinear photons per image frame per second generated by a wide-field multiphoton microscope compared to a scanning multiphoton microscope is given by[3]

,

when assuming that the same peak intensity is used in both systems. Here n is the number of scanning points such that .

Limitations

- The limit to which the energy can be increased depends on laser system. Optical amplifiers such as a regenerative amplifier, can typically yield energies of up to mJ with lower repetition rates compared to oscillator based systems (e.g. Ti:sapphire laser).

- Possible damage of the optics if the beam is focused somehow somewhere in the optical system to a small area. Different methods exist to achieve the required illumination without risk of damaging the optics (see Methods).

- Depth cross-sectioning may be missing.

Advantages

- Ultrafast imaging. A single laser shot is needed to produce one image. The frame rate is thus limited to the repetition rate of the laser system or the frame rate of the CCD camera.

- Lower damage in cells. In aqueous systems (such as cells), medium to low repetition rates (1 – 200 kHz) allow for thermal diffusion to occur between illuminating pulses so that the damage threshold is higher than with high repetition rates (80 MHz).[8][9]

- The whole object can be observed simultaneously because of the wide-field illumination.

- Larger penetration depth in biological imaging compared to one-photon fluorescence due to the longer wavelengths required.

- Higher resolution than wide-field one-photon fluorescence microscopy.The optical resolution can be comparable or better than multiphoton scanning microscopes [].

Methods

There is the technical difficultly of achieving a large illumination area without destroying the imaging optics. One approach is the so-called spatiotemporal focusing[4][5] in which the pulsed beam is spatially dispersed by a diffraction grating forming a 'rainbow' beam that is subsequently focused by an objective lens.[5] The effect of focusing the 'rainbow' beam while imaging the diffraction grating forces the different wavelengths to overlap at the focal plane of the objective lens. The different wavelengths then only interfere at the overlapping volume, if no further spatial or temporal dispersion is introduced, so that the intense pulsed illumination is retrieved and capable of yielding cross-sectioned images. The axial resolution is typically 2-3 µm[4][5] even with structured illumination techniques.[10][11] The spatial dispersion generated by the diffraction grating ensures that the energy in the laser is spread over a wider area in the objective lens, hence reducing the possibility of damaging the lens itself. The main disadvantage of this technique is the further spatial and temporal dispersion that can be introduced by the presence of irregular objects or interfaces, particularly for deep tissue imaging (which is one of the main advantages of multiphoton microscopy over one-photon fluorescence).

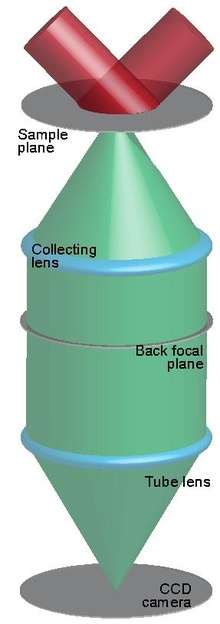

Another simpler method consists of two beams that are loosely focused and overlapped onto an area (~100 µm) on the sample.[2][3] With this method it is possible to have access to all the elements of the tensor thanks to the capability of being able to change the polarisation of each beam independently.

References

- ↑ Macias-Romero, Carlos; Didier, Marie E. P.; Jourdain, Pascal; Marquet, Pierre; Magistretti, Pierre; Tarun, Orly B.; Zubkovs, Vitalijs; Radenovic, Aleksandra; Roke, Sylvie (2014-12-15). "High throughput second harmonic imaging for label-free biological applications". Optics Express. 22 (25). doi:10.1364/oe.22.031102. ISSN 1094-4087.

- 1 2 3 Peterson, Mark D.; Hayes, Patrick L.; Martinez, Imee Su; Cass, Laura C.; Achtyl, Jennifer L.; Weiss, Emily A.; Geiger, Franz M. (2011-05-01). "Second harmonic generation imaging with a kHz amplifier [Invited]". Optical Materials Express. 1 (1). doi:10.1364/ome.1.000057.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Macias-Romero, Carlos; Didier, Marie E. P.; Jourdain, Pascal; Marquet, Pierre; Magistretti, Pierre; Tarun, Orly B.; Zubkovs, Vitalijs; Radenovic, Aleksandra; Roke, Sylvie (2014-12-15). "High throughput second harmonic imaging for label-free biological applications". Optics Express. 22 (25). doi:10.1364/oe.22.031102.

- 1 2 3 4 Cheng, Li-Chung; Chang, Chia-Yuan; Lin, Chun-Yu; Cho, Keng-Chi; Yen, Wei-Chung; Chang, Nan-Shan; Xu, Chris; Dong, Chen Yuan; Chen, Shean-Jen (2012-04-09). "Spatiotemporal focusing-based widefield multiphoton microscopy for fast optical sectioning". Optics Express. 20 (8). doi:10.1364/oe.20.008939.

- 1 2 3 4 Oron, Dan; Tal, Eran; Silberberg, Yaron (2005-03-07). "Scanningless depth-resolved microscopy". Optics Express. 13 (5). doi:10.1364/opex.13.001468.

- ↑ Shen, Y. R. (1989-02-09). "Surface properties probed by second-harmonic and sum-frequency generation". Nature. 337 (6207): 519–525. doi:10.1038/337519a0.

- ↑ Dadap, J. I.; Hu, X. F.; Russell, M.; Ekerdt, J. G.; Lowell, J. K.; Downer, M. C. (1995-12-01). "Analysis of second-harmonic generation by unamplified, high-repetition-rate, ultrashort laser pulses at Si(001) interfaces". IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Quantum Electronics. 1 (4): 1145–1155. doi:10.1109/2944.488693. ISSN 1077-260X.

- ↑ Macias-Romero, C.; Zubkovs, V.; Wang, S.; Roke, S. (2016-04-01). "Wide-field medium-repetition-rate multiphoton microscopy reduces photodamage of living cells". Biomedical Optics Express. 7 (4). doi:10.1364/boe.7.001458. ISSN 2156-7085.

- ↑ Harzic, R. Le; Riemann, I.; König, K.; Wüllner, C.; Donitzky, C. (2007-12-01). "Influence of femtosecond laser pulse irradiation on the viability of cells at 1035, 517, and 345nm". Journal of Applied Physics. 102 (11): 114701. doi:10.1063/1.2818107. ISSN 0021-8979.

- ↑ Choi, Heejin; Yew, Elijah Y. S.; Hallacoglu, Bertan; Fantini, Sergio; Sheppard, Colin J. R.; So, Peter T. C. (2013-07-01). "Improvement of axial resolution and contrast in temporally focused widefield two-photon microscopy with structured light illumination". Biomedical Optics Express. 4 (7). doi:10.1364/boe.4.000995.

- ↑ Yew, Elijah Y. S.; Choi, Heejin; Kim, Daekeun; So, Peter T. C. (2011-01-01). "Wide-field two-photon microscopy with temporal focusing and HiLo background rejection". 7903: 79031O–79031O–6. doi:10.1117/12.876068.