Wireless ad hoc network

A wireless ad hoc network (WANET) is a decentralized type of wireless network.[1][2] The network is ad hoc because it does not rely on a pre existing infrastructure, such as routers in wired networks or access points in managed (infrastructure) wireless networks.[3] Instead, each node participates in routing by forwarding data for other nodes, so the determination of which nodes forward data is made dynamically on the basis of network connectivity.[4] In addition to the classic routing, ad hoc networks can use flooding for forwarding data.

Wireless mobile ad hoc networks are self-configuring, dynamic networks in which nodes are free to move. Wireless networks lack the complexities of infrastructure setup and administration, enabling devices to create and join networks "on the fly" – anywhere, anytime.[5]

Introduction

A wireless ad-hoc network, also known as IBSS – Independent Basic Service Set, is a computer network in which the communication links are wireless. The network is ad-hoc because each node is willing to forward data for other nodes, and so the determination of which nodes forward data is made dynamically based on the network connectivity. This is in contrast to older network technologies in which some designated nodes, usually with custom hardware and variously known as routers, switches, hubs, and firewalls, forward all of the data. Minimal configuration and quick deployment make ad hoc networks suitable for emergency situations like natural or human-induced disasters, military conflicts.[6]

History

The earliest wireless data network is called "packet radio" network, and was sponsored by Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) in the early 1970s. Bolt, Beranek and Newman Technologies (BBN) and SRI International designed, built, and experimented with these earliest systems. Experimenters included Robert Kahn,[7] Jerry Burchfiel, and Ray Tomlinson.[8] Similar experiments took place in the Ham radio community. These early packet radio systems predated the Internet, and indeed were part of the motivation of the original Internet Protocol suite. Later DARPA experiments included the Survivable Radio Network (SURAN) project, which took place in the 1980s. Another third wave of academic activity started in the mid-1990s with the advent of inexpensive 802.11 radio cards for personal computers. Current wireless ad-hoc networks are designed primarily for military utility.[9] Problems with packet radios are: (1) bulky elements, (2) slow data rate, (3) unable to maintain links if mobility is high. The project did not proceed much further until the early 1990s when wireless ad hoc networks are born.

Early work

In the early 1990s, Charles Perkins from SUN Microsystems USA, and Chai Keong Toh from Cambridge University separately started to work on a different Internet, that of a wireless ad hoc network. Perkins was working on the dynamic addressing issues. Toh worked on a new routing protocol, which was known as ABR – Associativity-Based Routing.[10] Perkins eventually proposed AODV routing, which is based on link-state routing. Toh's proposal was an on-demand based routing, i.e. routes are discovered on-the-fly in real-time as and when is needed. Both ABR[11] and AODV are submitted to IETF as RFCs. ABR was implemented successfully into Linux OS on Lucent WaveLAN 802.11a enaled laptops and a practical ad hoc mobile network was therefore proven[1] to be possible in 1999. AODV was subsequently proven and implemented in 2005.[12] In 2007, David Johnson and Dave Maltz proposed DSR – Dynamic Source Routing.[13]

Application

The decentralized nature of wireless ad-hoc networks makes them suitable for a variety of applications where central nodes can't be relied on and may improve the scalability of networks compared to wireless managed networks, though theoretical and practical limits to the overall capacity of such networks have been identified. Minimal configuration and quick deployment make ad hoc networks suitable for emergency situations like natural disasters or military conflicts. The presence of dynamic and adaptive routing protocols enables ad hoc networks to be formed quickly. Wireless ad-hoc networks can be further classified by their application:

Mobile ad hoc networks (MANETs)

A mobile ad hoc network (MANET) is a continuously self-configuring, infrastructure-less network of mobile devices connected without wires.

Vehicular ad hoc networks (VANETs)

VANETs are used for communication between vehicles and roadside equipment. Intelligent vehicular ad hoc networks (InVANETs) are a kind of artificial intelligence that helps vehicles to behave in intelligent manners during vehicle-to-vehicle collisions, accidents. Vehicles are using radio waves to commnicate with each other.

Smartphone ad hoc networks (SPANs)

SPANs leverage the existing hardware (primarily Bluetooth and Wi-Fi) in commercially available smartphones to create peer-to-peer networks without relying on cellular carrier networks, wireless access points, or traditional network infrastructure.

Internet-based mobile ad hoc networks (iMANETs)

iMANETs are ad hoc networks that link mobile nodes and fixed Internet-gateway nodes.

Military and Tactical MANETs

Military and Tactical MANETs are used by military units with emphasis on security, range, and integration with existing systems.

A mobile ad-hoc network (MANET) is an ad-hoc network but an ad-hoc network is not necessarily a MANET.

Pros and cons

Pros

- No expensive infrastructure must be installed

- Use of unlicensed frequency spectrum

- Quick distribution of information around sender

- No single point of failure.

Cons

- All network entities may be mobile ⇒ very dynamic topology

- Network functions must have high degree of adaptability

- No central entities ⇒ operation in completely distributed manner.

Protocol stack

A major limitation with mobile nodes is that they have high mobility, causing links to be frequently broken and reestablished. Moreover, the bandwidth of a wireless channel is also limited, and nodes operate on limited battery power, which will eventually be exhausted. Therefore, the design of a mobile ad hoc network is highly challenging, but this technology has high prospects to be able to manage communication protocols of the future. The cross-layer design deviates from the traditional network design approach in which each layer of the stack would be made to operate independently. The modified transmission power will help that node to dynamically vary its propagation range at the physical layer. This is because the propagation distance is always directly proportional to transmission power. This information is passed from the physical layer to the network layer so that it can take optimal decisions in routing protocols. A major advantage of this protocol is that it allows access of information between physical layer and top layers (MAC and network layer).

Routing

Proactive routing

This type of protocols maintains fresh lists of destinations and their routes by periodically distributing routing tables throughout the network. The main disadvantages of such algorithms are:

- Respective amount of data for maintenance.

- Slow reaction on restructuring and failures.

Example: Optimized Link State Routing Protocol (OLSR)

Distance vector routing

As in a fix net nodes maintain routing tables. Distance-vector protocols are based on calculating the direction and distance to any link in a network. "Direction" usually means the next hop address and the exit interface. "Distance" is a measure of the cost to reach a certain node. The least cost route between any two nodes is the route with minimum distance. Each node maintains a vector (table) of minimum distance to every node. The cost of reaching a destination is calculated using various route metrics. RIP uses the hop count of the destination whereas IGRP takes into account other information such as node delay and available bandwidth.

Reactive routing

This type of protocol finds a route on demand by flooding the network with Route Request packets. The main disadvantages of such algorithms are:

- High latency time in route finding.

- Excessive flooding can lead to network clogging.[14]

Example: Ad hoc On-Demand Distance Vector Routing (AODV)

Flooding

Is a simple routing algorithm in which every incoming packet is sent through every outgoing link except the one it arrived on. Flooding is used in bridging and in systems such as Usenet and peer-to-peer file sharing and as part of some routing protocols, including OSPF, DVMRP, and those used in wireless ad hoc networks.

Hybrid routing

This type of protocol combines the advantages of proactive and reactive routing. The routing is initially established with some proactively prospected routes and then serves the demand from additionally activated nodes through reactive flooding. The choice of one or the other method requires predetermination for typical cases. The main disadvantages of such algorithms are:

- Advantage depends on number of other nodes activated.

- Reaction to traffic demand depends on gradient of traffic volume.[15]

Example: Zone Routing Protocol (ZRP)

Position-based routing

Position-based routing methods use information on the exact locations of the nodes. This information is obtained for example via a GPS receiver. Based on the exact location the best path between source and destination nodes can be determined.

Example: "Location-Aided Routing in mobile ad hoc networks" (LAR)

Technical requirements for implementation

An ad hoc network is made up of multiple "nodes" connected by "links."

Links are influenced by the node's resources (e.g., transmitter power, computing power and memory) and behavioral properties (e.g., reliability), as well as link properties (e.g. length-of-link and signal loss, interference and noise). Since links can be connected or disconnected at any time, a functioning network must be able to cope with this dynamic restructuring, preferably in a way that is timely, efficient, reliable, robust, and scalable.

The network must allow any two nodes to communicate by relaying the information via other nodes. A "path" is a series of links that connects two nodes. Various routing methods use one or two paths between any two nodes; flooding methods use all or most of the available paths.[16]

Medium-access control

In most wireless ad hoc networks, the nodes compete for access to shared wireless medium, often resulting in collisions (interference).[17] Collisions can be handled using centralized scheduling or distributed contention access protocols.[17] Using cooperative wireless communications improves immunity to interference by having the destination node combine self-interference and other-node interference to improve decoding of the desired signals.

Mathematical models

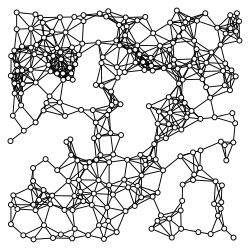

The traditional model is the random geometric graph.

These are graphs consisting of a set of nodes placed according to a point process in some usually bounded subset of the n-dimensional plane, mutually coupled according to a boolean probability mass function of their spatial separation (see e.g. unit disk graphs). The connections between nodes may have different weights to model the difference in channel attenuations.[17] One can then study network observables (such as connectivity,[18] centrality[19] or the degree distribution[20]) from a graph-theoretic perspective. One can further study network protocols and algorithms to improve network throughput and fairness.[17]

Security

Most ad hoc networks do not implement any network access control, leaving these networks vulnerable to resource consumption attacks where a malicious node injects packets into the network with the goal of depleting the resources of the nodes relaying the packets. To thwart or prevent such attacks, it was necessary to employ authentication mechanisms that ensure that only authorized nodes can inject traffic into the network.[21] Even with authentication, these networks are vulnerable to packet dropping or delaying attacks, whereby an intermediate node drops the packet or delays it, rather than promptly sending it to the next hop. Some behavior-based detection techniques have been developed to counter such attacks[22][23] in which a node overhears communication in the wireless neighborhood and determines if a neighbor is behaving correctly, i.e., forwarding the packet toward the intended recipient promptly.

Simulation

One key problem in wireless ad hoc networks is foreseeing the variety of possible situations that can occur. As a result, modeling and simulation (M&S) using extensive parameter sweeping and what-if analysis becomes an extremely important paradigm for use in ad hoc networks. Traditional M&S tools include NS2 (and recently NS3), OPNET Modeler, and NetSim.

However, these tools focus primarily on the simulation of the entire protocol stack of the system. Although this can be important in the proof-of-concept implementations of systems, the need for a more advanced simulation methodology is always there. Agent-based modeling and simulation offers such a paradigm. Not to be confused with multi-agent systems and intelligent agents, agent-based modeling[24] originated from social sciences, where the goal was to evaluate and view large-scale systems with numerous interacting "AGENT" or components in a wide variety of random situations to observe global phenomena. Unlike traditional AI systems with intelligent agents, agent-based modeling is similar to the real world. Agent-based models are thus effective in modeling bio-inspired and nature-inspired systems. In these systems, the basic interactions of the components of the system, also called a complex adaptive system, are simple but result in advanced global phenomena such as emergence.

See also

- 802.11

- Independent Basic Service Set (IBSS)

- List of ad hoc routing protocols

- Mobile ad hoc network (MANET)

- Personal area network (PAN)

- Wi-Fi Direct

References

- 1 2 Chai Keong Toh Ad Hoc Mobile Wireless Networks, Prentice Hall Publishers, 2002. ISBN 978-0-13-007817-9

- ↑ C. Siva Ram Murthy and B. S. Manoj, Ad hoc Wireless Networks: Architectures and Protocols, Prentice Hall PTR, May 2004. ISBN 978-0-13-300706-0

- ↑ Morteza M. Zanjireh; Hadi Larijani (May 2015). A Survey on Centralised and Distributed Clustering Routing Algorithms for WSNs (PDF). IEEE 81st Vehicular Technology Conference. Glasgow, Scotland. doi:10.1109/VTCSpring.2015.7145650.

- ↑ Morteza M. Zanjireh; Ali Shahrabi; Hadi Larijani (2013). ANCH: A New Clustering Algorithm for Wireless Sensor Networks (PDF). 27th International Conference on Advanced Information Networking and Applications Workshops. WAINA 2013. doi:10.1109/WAINA.2013.242.

- ↑ Chai Keong Toh. Ad Hoc Mobile Wireless Networks. United States: Prentice Hall Publishers, 2002.

- ↑ Ozan, K. Tonguz, Gianluigi Ferrari, John Wiley & Sons. ed. Ad Hoc Wireless Networks: A Communication-Theoretic Perspective,2006

- ↑ "Robert ("Bob") Elliot Kahn". A.M. Turing Award. Association for Computing Machinery.

- ↑ J. Burchfiel; R. Tomlinson; M. Beeler (May 1975). Functions and structure of a packet radio station (PDF). National Computer Conference and Exhibition. pp. 245–251. doi:10.1145/1499949.1499989.

- ↑ American Radio Relay League. "ARRL's VHF Digital Handbook", p 1-2, American Radio Relay League,2008

- ↑ Chai Keong Toh Associativity-Based Routing for Ad Hoc Mobile Networks, Wireless Personal Communications Journal, 1997.

- ↑ Chai Keong Toh IETF MANET DRAFT: Long-lived Ad Hoc Routing based on the Concept of Associativity

- ↑ "AODV Implementation Design and Performance Evaluation" by Ian D. Chakeres

- ↑ The Dynamic Source Routing Protocol (DSR) for Mobile Ad Hoc Networks for IPv4

- ↑ C. Perkins, E. Royer and S. Das: Ad hoc On-demand Distance Vector (AODV) Routing, RFC 3561

- ↑ Roger Wattenhofer. Algorithms for Ad Hoc Networks.

- ↑ Wu S.L., Tseng Y.C., "Wireless Ad Hoc Networking, Auerbach Publications", 2007 ISBN 978-0-8493-9254-2

- 1 2 3 4 Guowang Miao; Guocong Song (2014). Energy and spectrum efficient wireless network design. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 1107039886.

- ↑ M.D. Penrose. "Connectivity of Soft Random Geometric Graphs". arXiv:1311.3897

.

.

- ↑ A.P. Giles; O. Georgiou; C.P. Dettmann. "Betweenness Centrality in Dense Random Geometric Networks". arXiv:1410.8521

.

.

- ↑ M.D. Penrose (2003). "Random Geometric Graphs". Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Sencun Zhu; Shouhuai Xu; Sanjeev Setia; Sushil Jajodia (2003). "LHAP: A Lightweight Hop-by-Hop Authentication Protocol For Ad-Hoc Networks" (PDF). doi:10.1109/ICDCSW.2003.1203642.

- ↑ Khalil, Issa; Bagchi, Saurabh (2008-01-01). "MISPAR: Mitigating Stealthy Packet Dropping in Locally-monitored Multi-hop Wireless Ad Hoc Networks". Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Security and Privacy in Communication Netowrks. SecureComm '08. New York, NY, USA: ACM: 28:1–28:10. doi:10.1145/1460877.1460913. ISBN 9781605582412.

- ↑ Shila, D. M.; Cheng, Y.; Anjali, T. (2010-05-01). "Mitigating selective forwarding attacks with a channel-aware approach in WMNS". IEEE Transactions on Wireless Communications. 9 (5): 1661–1675. doi:10.1109/TWC.2010.05.090700. ISSN 1536-1276.

- ↑ Muaz Niazi; Amir Hussain (March 2009). "Agent based Tools for Modeling and Simulation of Self-Organization in Peer-to-Peer, Ad Hoc and other Complex Networks, Feature Issue" (PDF). IEEE Communications Magazine. Cs.stir.ac.uk. pp. 163–173.