Zack Taylor (baseball)

| Zack Taylor | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Catcher / Coach / Manager / Scout | |||

|

Born: July 27, 1898 Yulee, Florida | |||

|

Died: September 19, 1974 (aged 76) Orlando, Florida | |||

| |||

| MLB debut | |||

| June 15, 1920, for the Brooklyn Robins | |||

| Last appearance | |||

| September 24, 1935, for the Brooklyn Dodgers | |||

| MLB statistics | |||

| Batting average | .261 | ||

| Home runs | 9 | ||

| Runs batted in | 311 | ||

| Games managed | 649 | ||

| Managerial record | 235–410 | ||

| Winning % | .364 | ||

| Teams | |||

|

As player

As manager | |||

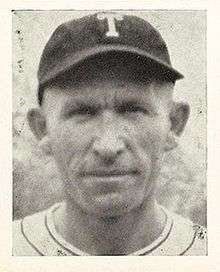

James Wren "Zack" Taylor (July 27, 1898 – September 19, 1974) was an American professional baseball player, coach, scout and manager.[1] He played in Major League Baseball as a catcher with the Brooklyn Robins, Boston Braves, New York Giants, Chicago Cubs, New York Yankees, and again with the Brooklyn Dodgers. Although Taylor was not a powerful hitter, he sustained a lengthy career in the major leagues due to his valuable defensive abilities as a catcher. After his playing career, he became better known as the manager for the St. Louis Browns owned by Bill Veeck.[2] His baseball career spanned 58 years.[2]

Baseball playing career

A native of Yulee, Florida, Taylor began his professional baseball career at the age of 16 with the Valdosta Millionaires during the 1915 season.[3] After playing in the minor leagues for five seasons, he made his major league debut with the Brooklyn Robins on June 15, 1920 at the age of 21.[1] He became the Robins' main catcher in 1923, succeeding Hank DeBerry. Although he led National League catchers in errors and in passed balls, he also led in range factor, assists and baserunners caught stealing while batting .288 in 93 games.[1][4]

In 1924, his batting average improved to .290 and he led the league's catchers in range factor and fielding percentage.[1] Taylor had his best offensive season in 1925, posting career highs with a .310 batting average, 3 home runs and 44 runs batted in.[1] He developed a reputation as one of the best catchers in the National League, finishing the season with 102 assists and leading the league's catchers with 64 baserunners caught stealing.[5][6] He had a talent for catching the spitball, and became the personal catcher for future Baseball Hall of Fame inductee Burleigh Grimes, the last pitcher allowed to throw the spitball in the major leagues.[7] On October 6, 1925, Taylor was traded by the Robins with Eddie Brown and Jimmy Johnston to the Boston Braves for Jesse Barnes, Gus Felix and Mickey O'Neil.[6]

After a season and a half with the Braves, he was traded to John McGraw's New York Giants along with Larry Benton and Herb Thomas for Doc Farrell, Kent Greenfield and Hugh McQuillan.[8] The Giants had acquired Burleigh Grimes in another trade and wanted Taylor to be his personal catcher.[7] Despite catching Grimes' team-leading 19 wins and performing well defensively to help the Giants finish the season just two games behind the pennant-winning Pittsburgh Pirates, McGraw released Taylor back to the Braves for the waiver price of $4,000 on February 28, 1928, the same day Grimes was traded to Pittsburgh.[9][10] McGraw said he regretted releasing the 29-year-old Taylor, but that he wanted to give younger catchers such as Shanty Hogan a chance to play.[10] Taylor took over as the Braves' starting catcher for the 1928 season.[11]

Having been displaced by Al Spohrer as the Braves' starting catcher early in the 1929 season, Taylor's contract was sold to the Chicago Cubs for the waiver price of $7,500 in July after all the other teams in both the American and National Leagues had passed on him.[12][13] When the Cubs' future Hall of Fame catcher Gabby Hartnett suffered an arm injury early in 1929, Taylor filled in capably, helping the Cubs win the National League pennant.[13] He helped guide the Cubs' pitching staff to a league-leading 14 shutouts and finish second in team earned run average and strikeouts.[14][15] In the only postseason appearance of his career in the 1929 World Series against the Philadelphia Athletics, Taylor made only three hits but was cited as an unsung hero in a losing cause for the Cubs because of his consistent, unwavering defensive skills behind the plate.[16][17] When Hartnett returned from his injury in 1930, Taylor went back to being the Cubs' backup catcher. In 1932, Cub manager Rogers Hornsby credited Taylor with helping develop the skills of Lon Warneke, as the young pitcher led the league with 22 wins.[18][19]

After being released by the Cubs in November 1933, he appeared in four games for the Yankees in 1934 before ending his playing career as a player-coach with the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1935.[1] He played his final major league game on September 24, 1935 at the age of 36,[1] and returned to the minor leagues as player-manager for the San Antonio Missions from 1937 to 1939 and the Toledo Mud Hens from 1940 to 1941.[20]

Career statistics

In a sixteen-year major league career, Taylor played in 918 games, accumulating 748 hits in 2,865 at bats for a .261 career batting average, along with 9 home runs, 311 runs batted in and an on-base percentage of .304.[1] He ended his career with a .977 fielding percentage.[1] Taylor led National League catchers three times in range factor and in baserunners caught stealing, twice in assists and once in fielding percentage.[1] His 49.63% career caught stealing percentage ranks 19th all-time among major league catchers.[21]

Managerial and coaching career

Taylor joined the St. Louis Browns as a coach in the midseason of 1941, and was a member of the 1944 Browns team that won the American League pennant – the team's only championship in its 52 years in St. Louis, although they eventually lost to the St. Louis Cardinals in the 1944 World Series.[22] When Luke Sewell resigned as manager in 1946, Taylor took over as the interim manager,[23] finished the season, then joined the coaching staff of the 1947 Pittsburgh Pirates. After Muddy Ruel managed the Browns to a last-place, 59–95 record in 1947 campaign, St. Louis general manager Bill DeWitt re-hired Taylor to be the manager. He lost 100 games in two of his five seasons as the manager of the under-funded Browns, and was fired after the 1951 season.[23]

Taylor was the St. Louis manager who, upon orders from then-owner Bill Veeck, called on Eddie Gaedel to pinch hit during a game on August 19, 1951 against Bob Cain and the Detroit Tigers.[2][24] He also participated in another Veeck stunt, in which the Browns handed out placards – reading take, swing, bunt, etc. – to fans and allowed them to make managerial decisions for a day. Taylor dutifully surveyed the fans' advice and relayed the sign accordingly.[25] The Browns won the game.

Taylor remained active in baseball as a scout for the Chicago White Sox and the Milwaukee and Atlanta Braves until his death.[2][26]

Later life

In 1974, Taylor was inducted into the Florida Sports Hall of Fame.[27] He died from a heart attack while at his home near Orlando, Florida, on September 19, 1974 at the age of 76.[2]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "Zack Taylor statistics". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved 3 January 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Zack Taylor Dead At 76". The Milwaukee Sentinel. Associated Press. 20 September 1974. p. 5. Retrieved 4 January 2012.

- ↑ "Zack Taylor minor league statistics". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved 4 January 2012.

- ↑ "1923 National League Fielding Leaders". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved 3 January 2012.

- ↑ "1925 National League Fielding Leaders". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved 4 January 2012.

- 1 2 "Robins And Braves In Deal". The Reading Eagle. 7 October 1925. p. 20. Retrieved 3 January 2012.

- 1 2 "Johnny Will Be Special Catcher". The Pittsburgh Press. 9 April 1928. p. 30. Retrieved 6 June 2012.

- ↑ "Giants Get Better Of Deal". The Milwaukee Journal. 13 June 1927. Retrieved 3 January 2012.

- ↑ "1927 New York Giants". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved 6 June 2012.

- 1 2 "Giants Send Zack Taylor To Braves On Waivers". The Meriden Record. Associated Press. 29 February 1928. p. 4. Retrieved 3 January 2012.

- ↑ "Coming Of Rajah Puts New Life In Braves". The Evening Independent. 10 March 1928. p. 4. Retrieved 3 January 2012.

- ↑ "Braves Sell Taylor to Cubs for $7500". The Milwaukee Journal. Associated Press. 7 July 1929. Retrieved 3 January 2012.

- 1 2 "Weak Spots Keep Cubs And Macks From Greatness Reached In Other Decades By Teams Of Same Cities". The Evening Independent. NEA. 2 October 1929. p. 7. Retrieved 3 January 2012.

- ↑ "1929 National League Team Pitching Statistics". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved 4 January 2012.

- ↑ "Can Bruins Hit Mack's Hurlers?". The Toledo News-Bee. 19 September 1929. p. 18. Retrieved 4 January 2012.

- ↑ "Zack Taylor Post-Season Statistics". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved 4 January 2012.

- ↑ "Series Superlatives Each Baseball Legend". The Milwaukee Journal. United Press International. 15 October 1929. p. 2. Retrieved 4 January 2012.

- ↑ "1932 National League Pitching Leaders". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved 4 January 2012.

- ↑ "How Warneke Got Control". The Reading Eagle. 20 July 1932. p. 10. Retrieved 4 January 2012.

- ↑ "Zack Taylor minor league managerial record". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved 4 January 2012.

- ↑ "Career Leaders & Records for Caught Stealing Percentage". Baseball Reference. Retrieved 23 September 2016.

- ↑ "1944 World Series". Baseball Reference. Retrieved 18 January 2011.

- 1 2 "Zack Taylor managerial statistics". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved 4 January 2012.

- ↑ "August 19, 1951 Tigers-Browns box score". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved 4 January 2012.

- ↑ Mike Shatzkin; Stephen Holtje; James Charlton (1990). The Ballplayers. New York: Arbor House/William Morrow. ISBN 0-87795-984-6.

- ↑ "Braves Hire Zack Taylor As Dixie Scout". The Milwaukee Sentinel. 9 February 1961. p. 8. Retrieved 4 January 2012.

- ↑ "Zack Taylor dies". The Ellensburg Daily Record. United Press International. 20 September 1974. Retrieved 4 January 2012.

External links

- Career statistics and player information from Baseball-Reference, or Baseball-Reference (Minors)

- Find-A-Grave biography