Zoetrope

A zoetrope is one of several pre-film animation devices that produce the illusion of motion by displaying a sequence of drawings or photographs showing progressive phases of that motion.

Etymology

The name Zoetrope was composed from the Greek root words ζωή zoe, "life" and τρόπος tropos, "turning" as a transliteration of "Wheel of life".

Technology

The zoetrope consists of a cylinder with slits cut vertically in the sides. On the inner surface of the cylinder is a band with images from a set of sequenced pictures. As the cylinder spins, the user looks through the slits at the pictures across. The scanning of the slits keeps the pictures from simply blurring together, and the user sees a rapid succession of images, producing the illusion of motion. From the late 19th century, devices working on similar principles have been developed, named analogously as linear zoetropes and 3D zoetropes, with traditional zoetropes referred to as "cylindrical zoetropes" if distinction is needed.

The zoetrope works on the same principle as its predecessor, the phenakistoscope, but is more convenient and allows the animation to be viewed by several people at the same time. Instead of being radially arrayed on a disc, the sequence of pictures depicting phases of motion is on a paper strip. For viewing, this is placed against the inner surface of the lower part of an open-topped metal drum, the upper part of which is provided with a vertical viewing slit across from each picture. The drum, on a spindle base, is spun. The faster the drum is spun, the smoother the animation appears.

Possible earlier versions

An earthenware bowl from Iran, over 5000 years old, could be considered a predecessor of the zoetrope. This bowl is decorated in a series of images portraying a goat jumping toward a tree and eating its leaves.[1] The images are sequential and seem evenly distributed around the bowl, but the bowl would have to rotate quite fast and steady while a stroboscopic effect is needed for the images to appear as an animation. In theory this could have been done with the well timed waving of a hand in front of the pictures on the bowl or in front of the viewer's eyes, while the bowl was spun on a potter's wheel. It remains very uncertain if the artist who created the bowl actually intended to create an animation.

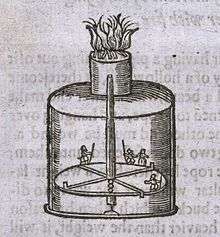

According to a fourth century Chinese historical text, the first century BCE Chinese Han craftsman Din Huan created a lamp with a circular band with images of birds and animals that moved "quite naturally" when the heat of the lamp caused the band to rotate. However, it is unclear whether this really created the illusion of motion or whether the account was an interpretation of the actual movement of the pictures of animals.[2] Possibly the same device was referred to as "umbrella lamp" and called "a variety of zoetrope" which "may well have originated in China" by historian of Chinese technology Joseph Needham. It had pictures painted on thin panes of paper or mica on the sides of a light cylindrical canopy bearing vanes at the top. When placed over a lamp it would give an impression of movement of animals or men. Needham mentions several other descriptions of figures moving after the lighting of a candle or lamp, but some of these have a semi-fabulous context or can be compared to heat operated carousel toys.[3] It is possible that all these early Chinese examples were actually the same as, or very similar to, the "trotting horse lamp" [走馬燈] known in China since before 1000 CE. This is a lantern which on the inside has cut-out silhouettes or painted figures attached to a shaft with a paper vane impeller on top, rotated by heated air rising from a lamp. The moving silhouettes are projected on the thin paper sides of the lantern.[4] These pictures are not animated.

John Bate described a simple device in his 1634 book "The Mysteries of Nature and Art". It consisted of picture cards on the four spokes of a wheel which was turned around by heat inside a glass or horn cylinder, "so that you would think the immages to bee living creatures by their motion".[5] Bate did not state that the pictures should be of different phases of one movement and the illustration shows figures that would not display a convincing animation (and are not situated on cards, in contradiction to what the text describes).

Invention

Simon Stampfer, one of the inventors of the phenakistoscope animation disc (or "stroboscope discs" as he called them), suggested in July 1833 in a pamphlet about his invention that the sequence of images for the animation could be placed on either a disc, a cylinder or a looped strip of paper or canvas stretched around two parallel rollers.[6] Stampfer chose to publish his invention in the shape of a disc.

After taking notice of Joseph Plateau's invention of the phénakisticope (published in London as "phantasmascope") British mathematician William George Horner thought up a cylindrical variation and published details about its mathematical principles in January 1834.[7] He called his device the "dædaleum" (sometimes misspelled "daedalum" or "daedatelum") as a reference to the Greek myth of Daedalus, but often erroneously claimed to mean "the wheel of the devil".[8] Horner's revolving drum had viewing slits between the pictures instead of above them as most later zoetrope variations would have. Horner planned to publish the dædaleum with optician King, Jr in Bristol but it "met with some impediment probably in the sketching of the figures".[7]

_(crop).jpg)

In the next three decades the phénakisticope remained the more common animation device, while relatively few experimental variations followed the idea of Horner's dædaleum. Most of these devices were intended for viewing photographic sequences, often with a stereoscopic effect.[8] These included Johann Nepomuk Czermak's Stereophoroskop, about which he published an article in 1855 [9] and several variations patented in 1860 by Peter Hubert Desvignes.[8] His Mimoscope, exhibited at the 1862 International Exhibition in London, could 'exhibit drawings, models, single or stereoscopic photographs, so as to animate animal movements, or that of machinery, showing various other illusions.'[10]

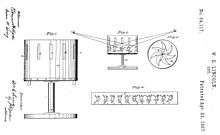

William Ensign Lincoln invented the definitive zoetrope in 1865 when he was circa 18 years old and a sophomore at Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island. Lincoln's patented version had the viewing slits on a level above the pictures, which allowed the use of easily replaceable strips of images. It also had an illustrated paper disc on the base, which was not always exploited on the commercially produced versions. On advice of a local bookstore owner, Lincoln sent a model to color lithographers and board manufacturers Milton Bradley and Co.[8] On December 15, 1866 the zoetrope was first advertised in the United States.[11] A little later it was first patented in the UK under no. 629 on March 6, 1867 by Henry Watson Hallett (as a communication to him by Milton Bradley)[8] and in the USA as the Zoëtrope on April 23, 1867 by William E. Lincoln as an assignor to Milton Bradley.[12] Over the years Milton Bradley released at least 7 numbered series with 12 strips of zoetrope pictures, a set with twelve designs showing the gradual transformations from one isometric form to another,[13] and one separately available strip showing the progress of the Grecian bend (a woman morphing into a camel).[8] The London Stereoscopic & Photographic Company was licensed as the British publisher and repeated most of the Milton Bradley animations, while adding a set of twelve animations by famous British illustrator George Cruikshank in 1870.[14]

The praxinoscope was an improvement on the zoetrope that became popular toward the end of the 19th century.[15] It replaced the zoetrope's narrow viewing slits with an inner circle of mirrors that intermittently reflected the images.

For displaying moving images, zoetropes were largely displaced by more advanced technology, notably film and later television.

Linear zoetropes

A linear zoetrope consists of an opaque linear screen with thin vertical slits in it. Behind each slit is an image, often illuminated. A motion picture is seen by moving past the display.

Linear zoetropes have several differences compared to cylindrical zoetropes due to their different geometries. Linear zoetropes can have arbitrarily long animations and can cause images to appear wider than their actual sizes.

Subway zoetropes

United States

In September 1980, independent filmmaker Bill Brand installed a type of linear zoetrope he called the "Masstransiscope" in an unused subway platform at the former Myrtle Avenue station on the New York City Subway. It consists of a wall with 228 slits; behind each slit is a hand-painted panel, and riders of passing trains see a motion picture. After falling into a state of disrepair, the "Masstransiscope" was restored in late 2008.[16] Since then, a variety of artists and advertisers have begun to use subway tunnel walls to produce a zoetrope effect when viewed from moving trains.

Joshua Spodek, as an astrophysics graduate student, conceived of and led the development of a class of linear zoetropes that saw the zoetrope's first commercial success in over a century. A display of his design debuted in September 2001 in the Atlanta subway system tunnel and showed an advertisement to riders moving past. The display is internally lit and nearly 980 feet (300 m) long, with an animation lasting around 20 seconds. His design soon appeared, both commercially and artistically, in subway systems around North America, Asia, and Europe.[17]

In April 2006, the Washington Metro installed advertisement zoetropes between the Metro Center and Gallery Place subway stations.[18] A similar advertisement was installed on the PATH train in New Jersey, between the World Trade Center and Exchange Place stations.

At around the same time, the San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) system installed a zoetrope-type advertisement between the Embarcadero and Montgomery stations which could be viewed by commuters traveling in either direction. The BART ads are still visible, though they are changed infrequently: a particular ad may remain up for several months before being replaced.

The New York City Subway hosted two digital linear zoetropes through its Arts for Transit program. One, "Bryant Park in Motion", was installed in 2010 at the Bryant Park subway station, and was created by Spodek and students at New York University's Tisch School of Arts' Interactive Telecommunications Program.[19] The other, "Union Square in Motion", was installed in 2011 by Spodek and students and alumni from Parsons the New School for Design's Art, Media, and Technology program in the Union Square station.[20]

Other places

The Kiev Metro (in Kiev, Ukraine) also featured an advertisement about 2008 for Life mobile telephone carrier in one of its subway tunnels that featured the zoetrope effect. It was quickly taken down.

In Mexico City, Mexico, an advertisement for the Honda Civic featuring a zoetrope effect was placed in one of the Line 2 tunnels.

3D zoetropes

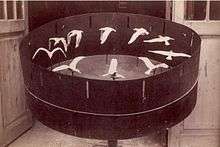

3D zoetropes apply the same principle to three-dimensional models. This variation was suggested by several inventors including Étienne-Jules Marey, who in 1887 used a large zoetrope to animate a series of plaster models based on his chronophotographs of birds in flight.[21] Modern equivalents normally dispense with the slitted drum and instead use a rapidly flashing strobe light to illuminate the models, producing much clearer and sharper distortion-free results. The models are mounted on a rotating base and the light flashes on and off within an extremely small fraction of a second as each successive model passes the same spot. The stroboscopic effect makes each seem to be a single animated object. By allowing the rotation speed to be slightly out of synchronization with the strobe, the animated objects can be made to appear to also move slowly forwards or backwards, according to how much faster or slower each rotation is than the corresponding series of strobe flashes.

Ghibli

The Ghibli Museum in Tokyo, Japan hosts a 3D zoetrope featuring characters from the animated movie My Neighbour Totoro. The zoetrope is accompanied by an explanatory display, and is part of an exhibit explaining the principles of animation and historical devices.

Toy Story

Pixar created a 3D zoetrope inspired by Ghibli's for its touring exhibition, which first showed at the Museum of Modern Art and features characters from Toy Story. Two more 3D zoetropes have been created by Pixar, both featuring 360-degree viewing. One was installed at Disney California Adventure Park, sister park to Disneyland, but has since been moved to The Walt Disney Studios Lot in Burbank, CA. The other is installed at Hong Kong Disneyland. The original Toy Story zoetrope still travels worldwide and has been shown in: London, England; Edinburgh, Scotland; Melbourne, Australia; Seoul, South Korea; Helsinki, Finland; Monterrey, Mexico; Taipei, Taiwan; Kaohsiung, Taiwan; Singapore; Shanghai, China; and Hamburg, Germany. It is currently on display at the exhibition for the Pixar's 25th anniversary at Amsterdam Expo in Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

All Things Fall

This zoetrope is created by the British artist Mat Collishaw and is inspired by a painting by Ippolito Scarsella of The Massacre of Innocents.[22] The work, named "All things Fall", presented during the solo exhibition "Black Mirror" at Galleria Borghese in Rome is made of steel, aluminium, plaster, resin, lit by LED lights and powered by an electric motor. Of his work, Collishaw says: “The zoetrope literally repeats characters to create an overwhelming orgy of violence that is simultaneously appalling and compelling.” It was originally designed in three dimensions. Each model figure was 3D printed in ABS printing. The ABS material is a special strong plastic used in this additive prototype systems called FDM.

Peter Hudson

Over the period 2002–2016, Peter Hudson and the makers at Spin Art, LLC, have created multiple interactive 3D stroboscopic zoetrope art installations. This began with "Sisyphish" (2002),[23] a human powered zoetrope that used strobe light to animate human figures swimming on a large rotating disk. Sisyphish, sometimes called the Playa Swimmers,[24] was originally unveiled at the arts and culture event, Burning Man, in the Black Rock Desert of Nevada.

Peter has since created stroboscopic zoetropes from 2004 to present including: "Deeper"[25] (2004), "Homouroboros"[26] (2007), "Tantalus"[27] (2008), and "Charon",[28] which toured Europe[29] and the United Kingdom in Summer of 2012.[30] The Charon zoetrope is built to resemble and rotate in the same kinetic fashion as a ferris wheel, stands at 32 feet high, weighs 8 tons and features twenty rowing skeleton figures[31] representing the mythological character, Charon, who carries souls of the newly deceased across the river Styx.

The most recent zoetrope creation is entitled "Eternal Return", took two years to build, and was unveiled in 2014 in the Black Rock Desert. Peter Hudson's zoetropes are based in San Francisco[32] are exhibited at various festivals and special events in the United States and internationally throughout the year.[33]

World record

In 2008, Artem Limited, a UK visual effects house, built a 10-meter wide, 10-metric ton zoetrope for Sony, called the BRAVIA-drome, to promote Sony's motion interpolation technology. It features 64 images of the Brazilian footballer Kaká. This has been declared the largest zoetrope in the world by Guinness World Records.[34][35]

Contemporary media uses

Since the late 20th century, zoetropes have seen occasional use for artwork, entertainment, and other media use, notably as linear zoetropes on subway lines, and from the early 21st century some 3D zoetropes.

In popular culture

Blue Man Group uses a zoetrope at their shows in Las Vegas and the Sharp Aquos Theater in Universal Studios (in Orlando, Florida).

The 1999 film House on Haunted Hill uses a man-sized zoetrope chamber as a twisted horror theme.

A zoetrope was used in the filming of the music video for "My Last Serenade" from Alive or Just Breathing (2002) by Killswitch Engage. It features a woman looking through the slits on a zoetrope while it moves; as she looks closer, the camera moves through the slits into the zoetrope, where the band is playing the song.

In 2007, an image of a zoetrope was unveiled as one of BBC Two's new idents: a futuristic city with flying cars seen through the shape of the number two.

In 2009 the E4 drama program Skins released silent preview clips of series four to coincide with their mash-up competition. One of the clips featured the character Emily Fitch looking into a zoetrope.

In 2011, Scott Blake created a "9/11 Zoetrope" allowing viewers to watch a continuous reenactment of United Airlines Flight 175 crashing into the South Tower of the World Trade Center.[36]

In 2012 animation studio Sehsucht, Berlin created the opener to the 2012 MTV Europe Music Awards. The CGI animation features a 3D zoetrope that shows a story of the American Dream. The animation followed the lives of Roxxy and Seth, who, through social media and popularity reach the height of their success playing at the EMA's atop the zoetrope carousel. It was directed by Mate Steinforth and produced by Christina Geller[37]

In 2013, director Jeff Zwart created a two-minute film, "Forza/Filmspeed", promoting Forza Motorsport 5. The production placed high resolution still images from the game on panels around Barber Motorsports Park and filmed them from a camera attached to a McLaren MP4-12C sports car.[38][39][40]

In the 2016 horror film The Conjuring 2, there is the usage of a zoetrope in one of the scenes.

See also

References

- ↑ Oldest Animation Discovered In Iran. Animation Magazine. 12-03-2008.

- ↑ Rojas, Carlos (2013). The Oxford Handbook of Chinese Cinemas. Oxford University Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-19-998844-0.

- ↑ Needham, Joseph (1962). Science and Civilization in China, vol. IV, part 1: Physics and Physical Technology. Cambridge University Press. p. 123-124.

- ↑ Yongxiang Lu. A History of Chinese Science and Technology, Volume 3. pp. 308–310.

- ↑ Bate, John (1654). The Mysteries of Nature and Art (PDF).

- ↑ Stampfer, Simon (1833). Die stroboscopischen Scheiben; oder, Optischen Zauberscheiben: Deren Theorie und wissenschaftliche Anwendung.

- 1 2 The London and Edinburgh Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science. 1834. p. 36.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Herbert, Stephen. (n.d.) From Daedaleum to Zoetrope, Part 1. Retrieved 2014-05-31.

- ↑ Czermak (1855). "Das Stereophoroskop" (in German).

- ↑ Hunt, Robert. Handbook to the industrial department of the International exhibition, 1862.

- ↑ Colman’s rural world. December 15, 1866. p. 366.

- ↑ https://docs.google.com/viewer?url=patentimages.storage.googleapis.com/pdfs/US64117.pdf

- ↑ Bradley's Game and Toy Catalogue. 1889-90.

- ↑

- ↑ Dulac, Nicolas; André Gaudreault (2004). "Heads or Tails: The Emergence of a New Cultural Series, from the Phenakisticope to the Cinematograph". Invisible Culture: A Journal for Visual Culture. The University of Rochester. Retrieved 2006-05-13.

- ↑ "Masstransiscope by Bill Brand". Retrieved 20 August 2015.

- ↑ "URBANPHOTO: Cities / People / Place » Tunnel Vision: Subway Zoetrope". URBANPHOTO: Cities / People / Place. Retrieved 20 August 2015.

- ↑ "Metro begins testing new tunnel ads", NBC4, April 4, 2006

- ↑ "Public Art". Joshua Spodek. Retrieved 20 August 2015.

- ↑ "Union Square display just up and beautiful!". Joshua Spodek. Retrieved 20 August 2015.

- ↑ Herbert, Stephen. (n.d.) From Daedaleum to Zoetrope, Part 2. Retrieved 2014-05-31.

- ↑ Factum Arte, S.L. "Factum Arte :: All things Fall". Retrieved 20 August 2015.

- ↑ "Peter Hudson Zoetrope Video and News". Hudzo.com. 2008-01-26. Retrieved 2013-10-02.

- ↑ Hobbs, Jess. "Support Peter Hudson's Charon". Voices of Burning Man. Retrieved April 2, 2011.

- ↑ "Peter Hudson Zoetrope Video and News". Hudzo.com. 2005-01-26. Retrieved 2013-10-02.

- ↑ "Homouroboros: Peter Hudson's Stroboscopic Zoetrope from 2007". Hudzo.com. 2011-03-24. Retrieved 2013-10-02.

- ↑ "Peter Hudson Zoetrope Video and News". Hudzo.com. 2009-08-27. Retrieved 2013-10-02.

- ↑ Even, Oddly. "Rowing Skeletons / "Charon" by Peter Hudson (Burning Man 2011)". www.oddly-even.com. Wordpress. Retrieved October 5, 2011.

- ↑ ""Charon" at Fusion Festival". http://wuestengefluester.axelvetter.de. External link in

|website=(help) - ↑ Fulcher, Merlin. "Secret Garden Party begins hunt for 2013 architectural visionaries". http://www.architectsjournal.co.uk/. EMAP Publishing Limited. Retrieved July 25, 2012. External link in

|website=(help) - ↑ Sunde, Lisa. "Charon". www.hudzodesign.com. Wordpress. Retrieved 2011. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ "Peter Hudson Bio". http://hudzodesign.com/bio/. External link in

|website=(help) - ↑ Rosato Jr., Joe (January 1, 2015). "San Francisco Artist Puts a New Spin on Old Art". NBC. NBC Bay Area Local News. Retrieved January 1, 2015.

- ↑ Murph, Darren (2008-12-21). "Sony sets Guinness World Record with BRAVIA-drome". Engadgethd.com. Retrieved 2009-07-29.

- ↑ "Sony Creates World's Largest Zoetrope". PopSci.com.au. 2009-02-18. Retrieved 2009-02-18.

- ↑ The Collected Works: How artists, writers, musicians, filmmakers, video-game designers, and quilters responded to the attacks of 9/11 – New York Magazine, Published August 27, 2011.

- ↑ Zoetrope Animation – MTV EMA Opener 2012 | Sehsucht

- ↑ Forza Motorsport 5: FilmSpeed [ESPN TV Commercial] Official Ad. YouTube. 19 September 2013. Retrieved 20 August 2015.

- ↑ "How The World's Fastest Camera Was Created for Forza Motorsport 5". Co.Create. Retrieved 20 August 2015.

- ↑ "'Forza Motorsport 5' goes meta in new TV spot". Retrieved 20 August 2015.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Zoetrope. |

- "From Daedaleum to Zoetrope", Part 1 and Part 2, by Stephen Herbert. Profusely illustrated and sourced. Retrieved 2014-05-25.

- Zoetrope (information on the zoetrope from the V&A Museum of Childhood)

- Further information and a picture can be found here.

- Burns, Paul The History of the Discovery of Cinematography An Illustrated Chronology

- A demonstration of similar optical toys, including the phenakistoscope, praxinoscope and thaumatrope

- Bill Brand's Masstransiscope can be found here.