Battle of Brice's Crossroads

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Battle of Brice's Crossroads, also known as the Battle of Tishomingo Creek and the Battle of Guntown, was fought on Friday, June 10, 1864, near Baldwyn, Mississippi, then part of the Confederate States of America. A Federal expedition from Memphis, Tennessee, of 4,800 infantry and 3,300 cavalry, under the command of Brigadier-General Samuel Sturgis, was defeated by a Confederate force of 3,500 cavalry under the command of Major-General Nathan Forrest.[1] The battle was a victory for the Confederates. Forrest inflicted heavy casualties on the Federal force and captured more than 1,600 prisoners of war, 18 artillery pieces, and wagons loaded with supplies. Once Sturgis reached Memphis, he asked to be relieved of command.[2][3]

Background

In March 1864, Lieutenant-General Ulysses Grant, newly named General in Chief of the Armies of the United States, and his most trusted subordinate Major-General William Sherman, planned a new, coordinated strategy to cripple the Confederacy and win the war. Grant would smash General Robert Lee's army in Virginia and head for Richmond. At the same time, Sherman would destroy the other main Confederate force, the Army of Tennessee, and seize the key city of Atlanta. Calling itself the "Gate City of the South," Atlanta was the strategic back door to the Confederate States. It was the South's most productive arsenal after Richmond and a critical transportation hub: Four railroads radiating from the city carried supplies to Confederate forces.[4]

Prelude

Sherman begin his Atlanta Campaign during the first week of May, moving slowly south while battling Confederate forces under General Joseph Johnston, an excellent defensive fighter. Johnston called in reinforcements, including Lieutenant-General Leonidas Polk and two divisions of his Army of Mississippi, which in turn left Major-General Stephen Lee in command of all remaining Confederate forces within Polk's Department of Alabama, Mississippi, and East Louisiana. Lee took charge of the department, but wisely gave Forrest authority to act independently in the northern part of Mississippi and Tennessee.[3][1]

During the four-month Atlanta Campaign, the U.S. Army advanced steadily, but in the process extended their supply lines that stretched back to Nashville. As the campaign progressed, Sherman grew concerned the brazen Forrest might move his Confederate cavalry force out of North Mississippi into Middle Tennessee, strike the supply lines, and perhaps jeopardize the entire Federal effort. As a result, Sherman in late May ordered Sturgis out of Memphis and into North Mississippi with a force of just over 8,000 men. Sturgis's mission was to keep Forrest occupied and, if possible, destroy the Confederate cavalry force that Forrest commanded. Sherman's orders to Sturgis came just in time, as Forrest's cavalry had just left for Middle Tennessee and was forced to turn back to Mississippi to once again defend the northern part of the state. The Federal expedition marched out of Memphis on June 1. Sturgis had a great deal of discretion in his movements, but was generally expected to "proceed to Corinth, Mississippi, by way of Salem and Ruckersville, capture any force that may be there, then proceed south, destroying the Mobile and Ohio Railroad to Tupelo and Okolona, and as far as possible toward Macon and Columbus."[3]

Battle

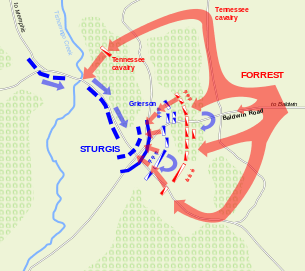

At 9:45 a.m., on June 10th, a brigade of Grierson's Cavalry Division reached Brice's Crossroads. The battle started at 10:30 a.m. when the Confederates performed a stalling operation with a brigade of their own. Forrest ordered the rest of his cavalry to converge around the crossroads. The remainder of the Federal cavalry arrived in support, but a strong Confederate assault soon pushed them back at 11:30 a.m., when the balance of Forrest's Cavalry Corps arrived on the scene. Grierson called for infantry support and Sturgis obliged. The line held until 1:30 p.m. when the first regiments of U.S. infantry arrived.

The Federal line, initially bolstered by the infantry, briefly seized the momentum and attacked the Confederate left flank, but Major-General Forrest launched an attack from his extreme right and left wings, before the rest of the Federal infantry could take the field. In this phase of the battle, Forrest commanded his field artillery to unlimber, unprotected, only yards from the Federal line, and to shred their troops with canister (Which in effect turns an artillery piece into a giant shotgun.) The massive damage caused Brigadier-General Sturgis to re-order his line in a tighter semicircle around Brice's Crossroads, facing east.

At 3:30, Forrest's 2d Tennessee Cavalry assaulted the bridge across the Tishomingo. Although the attack failed, it caused severe confusion among U.S. troops, and Sturgis ordered a general retreat. With the Tennesseans still pressing, the retreat bottlenecked at the Tishomingo bridge and a panicked rout developed instead. Sturgis' forces fled wildly, pursued on their return to Memphis across six counties before the exhausted Confederate attackers retired.

Aftermath

In correspondence with Brigadier-General Sturgis, Colonel Alex Wilkin, commander of the 9th Minnesota Infantry Regiment listed several reasons for the loss of the battle. He stated that General Sturgis, knowing that his men were under-supplied, having been on less than half rations, had been hesitant to advance on the enemy, but had done so against his better judgment because he had been ordered to do so. When the cavalry had engaged the enemy, many of the infantry had been ordered to advance double-time to support the cavalry. In their weakened condition, many had fallen out in the advance. Those who did arrive were exhausted at the beginning of the battle, while the Confederates were fresh and well fed, owing to a large supply in their rear.[2]

The roads to Tupelo were wet and sloppy due to six sequential days of rain, which slowed the advance of the supply wagons and ammunition train. Several men were detailed to try to make the roads passable. Additionally, the horses pulling the trains were poorly fed because there had been little in the way of forage for them to eat along the way. This accounted for Major-General Forrest's capture of the artillery and supplies. Intelligence had entirely favored the South, because the Confederates had been constantly fed information about the position and strength of the Federals from civilians in the area, while Brigadier-General Sturgis had received no such intelligence. Because of this information, Forrest planned to meet the Federals at a place where he could ambush Sturgis and make retreat as difficult as possible. This location was close to his supply depot, and very far from the U.S. Army's. When the retreat had occurred, with food and supplies exhausted, many of the Federal soldiers were unable to retreat with the rest because of fatigue. This was why so many Federals were taken prisoner during the battle. Finally, Wilkin stated that the rumors that Sturgis had been intoxicated at the battle were false.[2]

Legacy

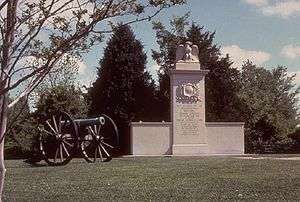

The Brice's Cross Roads National Historic Site, established in 1929, commemorates the Battle of Brice's Crossroads and is considered one of the best preserved of the American Civil War. The National Park Service erected and maintains monuments and interpretive panels on a small 1-acre (4,000 m2) plot at the crossroads. In 1994, concerned citizens organized the Brice's Crossroads National Battlefield Commission, Inc., to protect and preserve additional battlefield land. With assistance from the Civil War Trust, and the support of federal, state, and local governments, BCNBC has purchased for preservation over 1,330 acres (5.4 km2).[5] Much of the land was purchased from The Agnew Family, who still own some of the property that became the site of the battlefield. The modern Bethany Presbyterian Church is at the southeast side of the crossroads. At the time of the battle this congregation's meeting house was located further south along the Baldwyn Road. Bethany Cemetery, adjacent to the National Park Service monument, predates the American Civil War. Many of the area's earliest settlers are buried here. The graves of more than 90 Confederate soldiers killed at the crossroads are also located in Bethany Cemetery. Federal soldiers were buried in common graves, but were later reinterred in the Memphis National Cemetery.[6]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 —— & Hooker, Col. Charles E. (1899). Evans, [Brig.] Gen. Clement A., ed. Confederate Military History. Volume VII: Alabama and Mississippi. Atlanta, Ga.: Confederate Publishing Company. pp. 195–199. Retrieved April 9, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 Andrews, C. C., ed. (1891). Minnesota in the Civil and Indian Wars, 1861-1865. St. Paul, Minn.: Pioneer Press. pp. 420–426. LCCN 02014556. Retrieved April 9, 2016.

- 1 2 3 Wynne, Ben (2006). Mississippi's Civil War: A Narrative History (1st ed.). Macon, Georgia: Mercer University Press. pp. 158–161. ISBN 978-0-88146-039-1.

- ↑ Illustrated Atlas of The Civil War. Echoes of Glory (1st ed.). Alexandria, Virginia: Time Life Books. 1998. p. 248. ISBN 0-7370-3160-3.

- ↑ Zeller, Bob. "An Entire Battlefield Saved". Civil War Trust. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ↑ Thomas, William (1991). "Lost Confederate burial site discovered". Tulsa World. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

Further reading

- Bearss, Edwin C. (1971). "Protecting Sherman's Lifeline: The Battles of Brices Cross Roads and Tupelo 1864". National Park Service. Retrieved April 9, 2016.

- Brown, Dee (1998). Banash, Stan, ed. Dee Brown's Civil War Anthology (1st ed.). Santa Fe, N.M.: Clear Light. ISBN 1574160095. LCCN 98005448.

- Diary of Samuel A. Agnew, September 27, 1863 – June 30, 1864. Southern Historical Collection. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Retrieved April 9, 2016.

- National Park Service (n.d.). Update to the Civil War Sites Advisory Commission Report on the Nation's Civil War Battlefields Final DRAFT – State of Mississippi (PDF) (Report). Retrieved April 9, 2016.

External links

- Battle of Brice's Crossroads at the American Battlefield Protection Program

- Battle of Brice's Crossroads at the Civil War Trust

- Battle of Brice's Crossroads at HistoryAnimated.com

- Battle of Brice's Crossroads at the National Park Service

- Samuel A. Agnew Diary, 1851-1902 at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill