Chester Poe Cornelius

| Chester Poe Cornelius | |

|---|---|

Chester Poe Cornelius | |

| Born |

September 7, 1869 Oneida Nation of Wisconsin |

| Died | November 30, 1933 (aged 64) |

| Occupation | Native American lawyer and activist |

Chester Poe Cornelius ("Geyna") (September 7, 1869 – November 30, 1933) was an Oneida lawyer, scholar, activist and visionary. Cornelius, a descendent of distinguished Oneida leaders, collaborated with his sister Laura Cornelius Kellogg and her visionary "Lolomi Plan," a Progressive Era alternative to Bureau of Indian Affairs control, and presaged subsequent 20th-century movements to hold the federal government accountable to American Indians to preserve culture and communal lands in a protective sovereignty, to institute tribal self-government, and reclaim communal lands and promote economic development. Cornelius, a chief of the Oneida Tribe of Indians of Wisconsin, devoted much of his time to national Indian affairs and tribal organizations in the State of Oklahoma.

Early life

Chester Poe Cornelius was born on the Oneida Indian Reservation at Oneida, Wisconsin, on September 7, 1869, the eldest son of five children of Adam Poe and Celicia Bread Cornelius. Kellogg came from a distinguished lineage of Indian tribal leaders. His paternal grandfather was John Cornelius, Oneida chief and brother of Jacob Cornelius, also a chief, and his great-grandfather was Chief Dagoawi. His maternal grandfather was Chief Daniel Bread, known as Dehowyadilou “Great Eagle” (1800–1873), who helped find land for his people after the Oneidas were forcibly removed from New York State to Wisconsin in the early nineteenth century and averting their removal west of the Mississippi. When Dagoawi died he was still fighting to obtain land claim monies for Oneidas.[1]

Education

In late 1880's, Cornelius attended the Carlisle Indian School at Carlisle, Pennsylvania. He pursued higher education at Dickinson College in Carlisle, and later transferred to the University of Pennsylvania. He attended summer sessions at Harvard University and finally enrolled in the Eastman Business College in Poughkeepsie, New York, from which he received a diploma. In 1890, Cornelius was an Assistant Disciplinarian at the Carlisle Indian School. That year, speaking at the Mohonk Conference in New York, Kellogg remarked, "The way to exterminate the Indian is to absorb him into American civilization.[2] Sometime during the 1890s, Cornelius moved west to Indian Territory, now Oklahoma, and worked as a school teacher in the Indian Service at the Darlington Cheyenne and Arapaho Indian Reservation in El Reno, Oklahoma.[3] In 1896, Cornelius presented a paper on the issue of Indian citizenship to a national teachers conference.[4] On June 9, 1899, Kellogg married Laura Gertrude Smith in El Reno, and was reported to hold a position in the Indian Service in Oklahoma.[5]

In 1900, writer Hamlin Garland met Cornelius in El Reno, Oklahoma, and described him as "a giant in size and a man of ability who located here after a most astonishing career in New York." Garland credits Cornelius for suggesting that Indians be given standard surnames to protect their property rights during the land allotment process. At the time, there was no system of surnames for Indians through which legal titles could be traced, allotment of lands to individuals were, and the source of unnecessary confusion and litigation. After appealing to the Bureau of Indian Affairs, Garland was hired to manage the project for several years. [6]

The Lolomi Plan

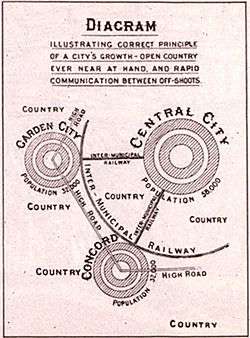

Around 1900, Cornelius returned to Wisconsin, where he studied law and was admitted to the bar.[7] Back home in Green Bay, Wisconsin, Cornelius joined with his sister Laura "Minnie" Cornelius Kellogg in her Lolomi Plan. The Lolomi Plan was based the upon the Garden city movement of urban planning that was initiated in 1898 by Sir Ebenezer Howard in the United Kingdom. Garden cities were intended to be planned, self-contained communities surrounded by "greenbelts", containing proportionate areas of residences, industry and agriculture. While touring Europe from 1908 to 1910, Minnie Kellogg developed a particular interest in garden cities in England, Germany and France, and visioned the model adapted to reservations to generate Native American economic self-sufficiency and tribal self-governance.[8]

Cornelius focused his legal career and full attention on their vision of uplifting the Oneida people. Chester was well versed in Indian laws as any Indian in the country, and made modern maps of the Oneida from which the other Indian maps of the country are now modeled.[9] Chester also was an expert in modern farming and live-stock production. In 1911, Outagamie County, Wisconsin, historian Thomas Henry Ryan noted Chester Poe Cornelius's vision. "It is his intention to forsake his profession and devote his whole life to making Oneida a garden spot of the country. The Oneida Stock Farm, with its most modern barns in the county and its acres presaging such wonderful possibilities, is an example of his idea of bringing beautiful culture out of the wilderness. In cooperation with his sister, Laura M. Cornelius, who has originated a scheme for industrial organization for all Indians, and who hopes to establish a Cherry Garden City for the Oneidas." [9] Historian Ryan, remarked, "C. P. Cornelius stands in a position to demonstrate to the world the large abilities and possibilities of the Indian race. Replying to the rebuke that he was foolish to give away so many of his ideas in improving farm machinery, which were not being patented, he replied, "There is nothing for which I have so much contempt as the social parasite. The man who has nothing to give to advance his fellows without the money first is one." [9]

Society of American Indians

Laura Cornelius Kellogg was a founding member of the Society of American Indians and a member of the first Executive Committee. On June 21 and 22, 1911, Minnie initiated a meeting of the Temporary Executive Committee at her home in Seymour, Wisconsin, to draft a letter announcing the association's formation and purpose. The meeting was attended by prominent Oneida attorneys Chester P. Cornelius and Dennison Wheelock.[10] On October 12, 1911, the Society’s inaugural conference was convened on the campus of the Ohio State University in Columbus, Ohio, symbolically held on Columbus Day as a fresh beginning for American Indians.[11] From October 12–17, 1911, approximately 50 prominent American Indian scholars, clergy, writers, artists, teachers and physicians attended the historic event, and was reported widely by national news media.[12] Chester was active at the conference and presented a discussion with the Honorable Charles D. Carter on the topic "Citizenship for the Indian." [13]

Keetoowah Nighthawk Society

In July 1914, Cornelius and his sister Minnie met Redbird Smith and his delegation while in Washington, D.C.[14] Redbird Smith was the spiritual leader of the Keetoowah Nighthawk Society, a traditionalist Cherokee faction who lived in isolated communities in the Wild Horse Mountains of northeastern Oklahoma. The Keetoowah Nighthawk Society secretly practiced the traditional ceremonies and gatherings of the pre-removal Cherokee culture, and resisted assimilation, allotment and dissolution of tribal government. After their meeting in Washington, Chief Smith invited Minnie and Chester to implement their Lolomi Plan for the Nighthawk Keetoowah. In 1915, Cornelius returned to Oklahoma and joined Smith and the Society.[15] The Keetoowah gave Minnie the Cherokee name "Egahtahyen" ("Dawn") and power of attorney to act on their behalf to establish a communal enterprise.[16] Chester became the spokesman for the Society, managed the Lolomi plan for Redbird Smith and worked to get the Ketoowah Society a reservation.[17] In 1916, through the efforts of Cornelius and local congressmen, a bill was introduced into Congress to allow the Ketoowah Society to incorporate as an industrial community, but it failed to pass.[17] In 1917, Cornelius pressed forward with the Lolomi plan. A herd of Black Angus cattle was purchased from the Oneida Stock Farm in Wisconsin and driven to Oklahoma, and many people from the area around Jay, Oklahoma, moved south and settled near Gore, Oklahoma.[17]

The Keetoowah Nighthawk Society placed great trust in Cornelius in matters of ritual and religion. He was an Indian, an educated man and came from the sacred direction, east[15] During this time, Cornelius helped the Keetoowah reestablish in some way the old tribal organization of the Cherokee Nation.[18] Cornelius was a scholar of Iroquois history and culture and interested in bringing Keetoowah ceremonies closer to Iroquois traditions. While the prehistoric origin of the Cherokee is shrouded in mystery, their language is Iroquoian and they shared many traditions with the Six Nations.[19] Cornelius believed that the Six Nations of the Iroquois had originally been seven nations or fires, and the Cherokee tribe had migrated south and was the seventh lost fire of the Iroquois.[15] At the suggestion of Cornelius, the Keetoowah adopted a number of ritualistic elements of the Iroquois culture that were compatible with Cherokee tradition.[20] After the innovations, the ritual organization of the Keetoowah fires very closely approximated the Cherokee town fires in aboriginal times.[21]

In November 1918, Redbird Smith died at the age of 68.[22] On the day of Redbird Smith's funeral, a large white crane flew from the east at sun rise and lit in a tree next to the stomp ground.[23] According to John Smith, the most influential Nighthawk leader among Redbird Smith's sons, "We were up in the stomp ground fixing to have services for my father when this crane was sitting in the tree near the stomp ground. C.P. Cornelius said, 'You watch and see if that crane isn't down by the graveyard when we bury your father.' Pretty soon the crane flew off and lit in a tree just west of the graveyard. When we carried my father's coffin down to the graveyard, the crane sat there in that tree and hollered. After we buried my father, the crane sat there until sundown and then flew off to the west." [23] This event was reported by the Cherokee as an omen, for a crane is very wild and hardly ever can one approach within fifty yards of it without flying away.[23]

Sam Smith, one of the sons of Redbird Smith, became chief of the Nighthawk Keetoowah Society, while Cornelius continued as spokesman and legal counsel.[17] Restrictions were removed from several allotments and they were mortgaged to fund and establish a bank in Gore with Cornelius as president.[18] In 1920, Kellogg published a book titled "Our Democracy in the American Indian", where she proposed a Lolomai Plan, later spelled Lolomi, which means "good, beautiful, wise" in the Hopi language.[24] Her book was "lovingly dedicated" to the memory of Chief Redbird Smith, spiritual leader of the Nighthawk Keetoowah, "who preserved his people from demoralization, and was the first to accept the Lolomi." In 1921, a hundred Cherokees from 35 families moved together to the southeastern corner of Cherokee County, Oklahoma, to create a traditional community.[25] By 1923, the Lolomi plan was progressing, and Kellogg told the Daily Oklahoman that he wanted the Keetoowah some day to be "in a position where they can work for the common good and build up a surplus for the good of the community." However, shortly thereafter, the bank at Gore failed. The cattle herd was taken by creditors and those who had mortgaged their allotments lost their land.[26] In the post War War I depression of the early 1920s, many sound banks and businesses failed, and the circumstances appear to have been beyond Cornelius's diligence.[26] George Smith, fifth son of Redbird Smith, recalled, "C.P. was awful smart. You couldn't get ahead of him. The white people was scared of him all the time, watching what he was doing with the Keetoowahs. He was a good man, but the white people were against him, and we had some bad luck." [26] After the collapse of the Lolomi Plan, some Keetoowahs believed that Cornelius cheated them and he was dismissed as spokesman for the Ketoowah Society.[27] Cornelius continued to reside in Gore and play a role in Indian affairs. In 1925, Cornelius was raised as a chief of the Oneida Nation of Wisconsin. In 1927, Cornelius was a member of the Resolution Committee of the Society of Oklahoma Indians, an organization representing 26 tribes.

Later Years

Cornelius was a Freemason, having obtained a thirty-second degree in the Scottish Rite and a Knight Templar. He also belonged to the Ancient Arabic Order of Nobles of the Mystic Shrine.[9] Chester Poe Cornelius died on November 30, 1933, and was buried at Greenhill Cemetery, Muskogee, Oklahoma. He was survived by a daughter, Mildred Cornelius.[28]

Legacy

Chester Poe Cornelius collaborated with his sister Laura Cornelius Kellogg and her visionary "Lolomi Plan," a Progressive Era alternative to Bureau of Indian Affairs control. While Chester and Minnie never fulfilled the expectations of their followers, their Lolomi Plan presaged subsequent 20th-century movements to hold the federal government accountable to American Indians to preserve culture and communal lands in a protective sovereignty, to institute tribal self-government, and reclaim communal lands and promote economic development.[29] The Lolomi vision is realized in the success of the Oneida Tribe of Indians of Wisconsin. Land holdings by the Oneida Tribe of Indians of Wisconsin have increased since the mid-1980s from approximately 200 acres to more than 18,000 acres. The economic impact on Brown County, Outagamie County and the metropolitan Green Bay, Wisconsin, area is estimated in excess of $250 million annually.[30]

References

- ↑ Thomas Henry Ryan, History of Outagamie County, Wisconsin (hereinafter "Thomas Henry Ryan"), Part 15, 1911, p.1059-1061.

- ↑ "The Mohonk Conference", Boston Post, October 10, 1890.

- ↑ "Indian Teachers: Program for the Big Conference in Lawrence in July", Lawrence Daily Journal, June 6, 1896.

- ↑ "The Indian Teachers are Visiting Today", Lawrence Daily Journal, July 16, 1896.

- ↑ "Indian and White Girl Wed", Kane Daily Republican, June 10, 1899.

- ↑ Hamlin Garland, Companions on the Trail, (1931).

- ↑ "State News", Oshkosh Daily Northwestern, December 27, 1900, p.4.

- ↑ Kristina Ackley, “Laura Cornelius Kellogg, Lolomi and Modern Oneida Placemaking”, (hereinafter "Kristina Ackley"), SAIL 25.2/AIQ 37.3 Summer 2013, P. 120, Patricia Stovey, "Opportunities at Home: Laura Cornelius Kellogg and Village Industrialization", (hereinafter "Stovey"), in Laurence M. Hauptman and L. Gordon McLester III, ed., The Oneida Indians in the Age of Allotment, 1860–1920, (2006), p.144.

- 1 2 3 4 Thomas Henry Ryan

- ↑ Laurence M. Hauptman, Seven Generations of Iroquois Leadership: The Six Nations Since 1800, (hereinafter "Hauptman"), (2006), p.149.

- ↑ Wilkins, 218. Waggoner, 190.

- ↑ Only 44 active members are listed in the program as being in attendance at the conference, out of a little more than 100 active members in total. The non-Indian Associates, 125 of them, outnumbered the Indians. Philip J. Deloria, “Four Thousand Invitations”, SAIL 25.2/AIQ 37.3 Summer 2013, P. 28.

- ↑ Report of the Executive Council on the Proceedings of the First Annual Conference of the Society of American Indians (1912), p. 21.

- ↑ Robert K. Thomas, "The Origin and Development of the Redbird Smith Movement", (hereinafter "Thomas"), Department of Anthropology, University of Arizona, (1954), p.182.

- 1 2 3 Thomas, p.182.

- ↑ Thomas, p.204-205.

- 1 2 3 4 Thomas, p.200-201.

- 1 2 Thomas, p.201.

- ↑ "CHEROKEE". digital.library.okstate.edu. Archived from the original on 2014-10-08. Retrieved 2014-09-26.

- ↑ Thomas, p.182-183.

- ↑ Thomas, p.187.

- ↑ Thomas, p.198.

- 1 2 3 Thomas, p.199.

- ↑ Cristina Stanciu, “An Indian Woman of Many Hats: Laura Cornelius Kellogg’s Embattled Search for an Indigenous Voice”, SAIL 25.2/AIQ 37.3 Summer 2013, P. 91-92.

- ↑ Conley, Robert. "The Dawes Commission and Redbird Smith." The Cherokee Nation: A History. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2005: p.203. ISBN 978-0-8263-3235-6.

- 1 2 3 Thomas, p.202.

- ↑ Thomas, p.202-203.

- ↑ Ewen, Alexander and Jeffrey Wollock. "Cornelius, Chester Poe." Encyclopedia of the American Indian in the Twentieth Century. New York: Facts On File, Inc., 2014.

- ↑ http://www.everyculture.com/multi/Le-Pa/Oneidas.html. p.145

- ↑ "Oneida Seven Generations Corporation". osgc.net. Retrieved 2014-09-26.