Electoral system of New Zealand

|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of New Zealand |

| Constitution |

|

|

|

Judiciary

|

|

Related topics |

The New Zealand electoral system has been mixed-member proportional (MMP) since 1996. MMP was introduced after a referendum in 1993. MMP replaced the first past the post (FPP) system New Zealand had previously used for most of its history.

New Zealand has one House of Representatives, usually with 120 members, although the number can increase because of (generally) one or two overhang seats, depending on the outcome of the electoral process. The term of the New Zealand Parliament is set at three years. Whichever party (or combination of parties) wins the most seats at the general election becomes the Government.

In contemporary New Zealand, generally all permanent residents and citizens over 18 are eligible to vote. The main exceptions are when a person has been living overseas continuously for too long, has been detained in a psychiatric hospital, or since 2010, is currently a sentenced prisoner.[1]

Historically, New Zealand was the first country in the world to give women the right to vote – in 1893. This meant that theoretically, New Zealand had universal suffrage from 1893, meaning all adults 21 years of age and older were allowed to vote. However, the voting rules that applied to the European settlers did not apply to Māori – and their situation is still unique, in that a number of seats in the New Zealand parliament are elected by Māori voters alone.

Term of parliament

Although Parliamentary elections are held every three years, this has not always been the case. In New Zealand's early colonial history, elections were held every five years – as established by The New Zealand Constitution Act of 1852. The term was reduced to three years in 1879 because of concerns about the growing power of central Government.[2]

Since then, the term has been altered three times – mainly in times of international crisis. During the First World War it was extended to five years. In the early 1930s, it was pushed out to four years. This proved to be unpopular with the electorate and after the election of 1935, the term was reduced to three years again. It was extended to four years once again during the Second World War, but returned to three years afterwards. In 1956, the term of three years was 'entrenched' in the Electoral Act which means that it can only be changed by achieving a majority in a national referendum or by a vote of 75% of all members of Parliament.[2]

In 2013 the Government established an advisory panel to conduct a review of constitutional issues – including an examination of the term of parliament. Other issues discussed at public meetings held by the panel were the number of MPs New Zealand should have, whether a written constitution is needed, and whether all legislation should be consistent with the Bill of Rights Act.[3] Both Prime Minister John Key and Opposition leader David Shearer expressed support for an extension of the parliamentary term to four years.[4] The main argument put forward in support of a longer term is that "Governments need time to establish and then implement new policies".

The last referendum on the term of parliament was in 1990 and found nearly 70% of the voters were opposed to extending the term. An opinion poll on the news website Stuff.co.nz in early 2013 found that of 3,882 respondents, 61% were in favour of changing to a four-year term.[5]

Māori seats

A unique feature of New Zealand's electoral system is that a number of seats in Parliament are reserved exclusively for Māori. However, this was not always the case. In the early colonial era, Maori could not vote in elections unless they owned land as individuals. European colonists were quite happy with this state of affairs because, according to NZ History online, "they did not think Maori were 'civilised' enough to exercise such an important responsibility".[6] At the time, Māori were dealing directly with the Crown in regard to the Treaty of Waitangi and had little interest in the 'pākehā parliament'.

During the wars of the 1860s, some settlers began to realise it was necessary to bring Māori into the British system if the two sides were to get along. After much debate, in 1867 Parliament passed the Maori Representation Act which established four electorates solely for Maori. The four Maori seats were a very minor concession; the settlers had 72 seats at the time and, on a per capita basis, Maori should have got up to 16 seats.[6] All Māori men (but not women) over the age of 21 were given the right to vote and to stand for Parliament.

Full blooded Maori had to vote in the Maori seats and only Maori with mixed parentage ('half-castes') were allowed to choose whether they voted in European electorates or Maori electorates. This dual voting system continued until 1975.[6] From time to time there was public discussion about whether New Zealand still needed separate seats for Maori – which some considered to be a form of apartheid. Maori were only allowed to stand for election in European seats (or general electorates) from 1967.

In 1985, a Royal Commission on the Electoral System was established. It concluded that "separate seats had not helped Maori and that they would achieve better representation through a proportional party-list system". The Commission recommended that if mixed member proportional (MMP) system was adopted, the Māori seats should be abolished. However, most Māori wanted to keep them and the seats were not only retained under MMP, their "number would now increase or decrease according to the results (population numbers) of the regular Māori electoral option". As a result, in 1996 before the first MMP election, the number of Māori seats increased to five – the first increase in 129 years. In 2002, it went up to seven.[7]

Developments in voting rights and eligibility

Secret ballot

In European seats, the secret ballot was introduced in 1870.[7] However, Māori continued to use a verbal system – whereby electors had to tell the polling official which candidate they wanted to vote for. Māori were not allowed a secret ballot until 1938 and even voted on a different day. According to NZ History online: "Up until 1951 Maori voted on a different day from Europeans, often several weeks later." It was not until 1951 that voting in the four Māori electorates was held on the same day as voting in the general election.[8]

NZ History also states: "There were also no electoral rolls for the Maori seats. Electoral officials had always argued that it would be too difficult to register Maori voters (supposedly because of difficulties with language, literacy and proof of identity). Despite frequent allegations of electoral irregularities in the Maori seats, rolls were not used until the 1949 election."[6]

Women's suffrage

In early colonial New Zealand, as in most Western countries, women were totally excluded from political affairs. Led by Kate Sheppard, a women's suffrage movement began in New Zealand in the late 19th century, and the legislative council finally passed a bill allowing women to vote in 1893.[9] This made New Zealand the first country in the world to give women the vote. However, they were not allowed to stand as candidates until 1919, and the first female Member of Parliament (Elizabeth McCombs) was not elected until 1933[9] – 40 years later. Although there have been two female Prime Ministers (Jenny Shipley and Helen Clark), women remain somewhat under-represented in Parliament.[9] Following the election in 2011, 39 MPs (almost one third) were women. After the 2011 election, on a global ranking New Zealand is 21st in terms of its representation of women in Parliament.[10]

Prisoners' right to vote

Restrictions have also been imposed on prisoners. In 2010, the National government passed The Electoral (Disqualification of Convicted Prisoners) Amendment Bill which removed the right of all sentenced prisoners to vote. The Attorney General said the new law was inconsistent with the Bill of Rights Act which says that "every New Zealand citizen who is over the age of 18 years has the right to vote and stand in genuine periodic elections of members of the House of Representatives".[11] Prior to the 2010 Act, only prisoners with a sentence of three years or more were not allowed to vote – which is also inconsistent with the Bill of Rights Act. The Electoral Disqualification Bill was also opposed by the Law Society and the Human Rights Commission who pointed out that, in addition to being inconsistent with the Bill of Rights, the legislation was also incompatible with various international treaties that New Zealand is party to.

Law Society Human Rights committee member, Frances Joychild, told Parliament's law and order committee that: "It is critical for the function of our democracy that we do not interfere with the right to vote." With specific reference to decisions made by courts in Canada, Australia and South Africa, and by the European Court of Human Rights in respect of the United Kingdom, she pointed out that "every comparable overseas jurisdiction has had a blanket ban (against prisoners' voting) struck down in the last 10 years".[12]

Election day

Until the 1938 election, elections were held on a weekday. In 1938 and in 1943, elections were held on a Saturday. In 1946 and 1949, elections were held on a Wednesday.[13] In 1950, the legal requirement to hold elections on a Saturday was introduced,[14] and this first applied to the 1951 election. Beginning with the 1957 election, a convention was formed to hold general elections on the last Saturday of November. This convention was upset by Robert Muldoon calling a snap election in 1984. It took until the 1999 election to get back towards the convention, only for Helen Clark to call an early election in 2002. By the 2011 election, the conventional 'last Saturday of November' was achieved again.[15] The last election was held on Saturday, 26 November 2011.[16] If the convention had been followed at the 2014 general election, it would have been held on 29 November 2014.

Prior to 1951, elections in Māori electorates were held on different days than elections in general electorates.[14] The table below shows election dates starting with the first election that was held on a Saturday in 1938:[17]

Key

| Election held on last Saturday of November |

MMP in New Zealand

Until 1994, New Zealand used the First past the post electoral system whereby whichever political party won the most seats on election day became the Government. This process favours two party systems and for the last 60 years, New Zealand elections have been dominated by the National Party and Labour Party. Smaller parties found it hard to gain representation and in 1994, New Zealand officially adopted mixed member proportional representation (MMP) as its electoral system. Its defining characteristic is a mix of members of Parliament (MPs) from single-seat electorates and MPs elected from a party list, with each party's share of seats determined by its share of the party vote nationwide.[18] The first MMP election was held in 1996. As a result, National and Labour lost their complete dominance in the House. Neither party has yet been able to govern on its own and has had to form coalitions to govern. The closest either party has come to governing alone was the 2014 election, when National won 60 seats, just 1 short of a majority.

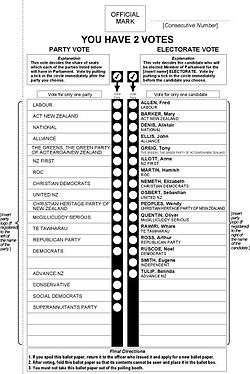

Under MMP, New Zealand voters have two votes. The first vote is the electorate vote. It determines the local representative for that electorate (constituency). The electorate vote works on a plurality system whereby whichever candidate gets the greatest number of votes in each electorate wins the seat. The second vote is the party vote. This determines the number of seats each party is entitled to overall – in other words, the proportionality of the House.

Thresholds: There are two thresholds in the New Zealand MMP system.[19] The first is that any Party which receives 5% or more of the Party vote is entitled to a share of the nominally 120 seats in the House of Representatives – even if the Party does not win a single electorate seat. For instance in the 2008 elections, the Greens failed to win any electorate seats but won 6.7% of the party vote and thereby earned nine seats in Parliament.[19]

The second threshold is that any Party that wins one or more electorate seats is entitled to additional (list) seats in parliament even if it doesn't win 5% of the Party vote. In 2008, the ACT Party won only 3.6% of the Party vote. But ACT got a total of five seats in Parliament because an ACT candidate won the Epsom electorate; this has been called the "coat-tailing" rule.[19] But the New Zealand First party which got 4.07% of the list vote or below the 5% threshold was not returned to parliament in 2008.

Seats in parliament are allocated to electorate MPs first. Then Parties fulfil their remaining quota (based on their share of the Party vote) from their list members. A closed list is used, and list seats are allocated by the Sainte-Laguë method, which favours minor parties more than the alternative D'Hondt method. If a Party has more electorate MPs than proportional seats, then it receives an overhang. If the Party does not have enough people on its list to fulfil its quota, then there is an underhang.

Strategic voting

The two largest parties National and Labour usually "top up" their electoral candidates with list candidates, so that supporting a candidate of a minor party allied with their party will not reduce the number of seats that the major party wins, but supporting the minor party will increase the number of MPs who support their party in coalition. This is called "strategic voting" or sometimes "tactical voting".

In several recent elections in New Zealand National has suggested that National supporters in certain electorates should vote for minor parties or candidates who can win an electorate seat and would support a National government. This culminated in the Tea tape scandal when a meeting in the Epsom electorate in 2011 was taped. The meeting was to encourage National voters in the electorate to vote "strategically" for the ACT candidate. Labour could have suggested to its supporters in the electorate to vote "strategically" for the National candidate, as the Labour candidate could not win the seat but a National win in the seat would deprive National of an ally. However, Labour chose not to engage in this tactic instead calling it a "sweetheart deal".[20]

2011 referendum and Electoral Commission 2012 report

A referendum on the voting system was held in conjunction with the 2011 general election, with 57.8% of voters voting to keep the existing Mixed Member Proportional (MMP) voting system. The majority vote automatically triggered under the Electoral Referendum Act 2010 an independent review of the workings of the system by the Electoral Commission.

The Commission released a consultation paper in February 2012 calling for public submissions on ways to improve the MMP system, with the focus put on six areas: basis of eligibility for list seats (thresholds), by-election candidates, dual candidacy, order of candidates on party lists, overhang, and proportion of electorate seats to list seats. The Commission released its proposal paper for consultation in August 2012, before publishing its final report on 29 October 2012. In the report, the Commission recommended the following:[21]

- Reducing the party vote threshold from 5 percent to 4 percent. If the 4 percent threshold is introduced, it should be reviewed after three general elections.

- Abolishing the one electorate seat threshold – a party must cross the party vote threshold to gain list seats.

- Abolishing the provision of overhang seats for parties not reaching the threshold – the extra electorates would be made up at the expense of list seats to retain 120 MPs

- Retaining the status quo for by-election candidacy and dual candidacy.

- Retaining the status quo with closed party lists, but increasing scrutiny in selection of list candidates to ensure parties comply with their own party rules.

- Parliament should give consideration to fixing the ratio between electorate seats and list seats at 60:40 (72:48 in a 120-seat parliament)

Parliament is responsible for implementing any changes to the system, which has been largely unchanged since it was introduced in 1994 for the 1996 election. In November 2012 a private member's bill under the name of opposition Labour Party member Iain Lees-Galloway was put forward to implement the first two recommendations, although the bill would have to be chosen in the member's bill ballot.[22] [23]

In May 2014 Judith Collins and John Key said that there was no inter-party consensus on implementing the results of the Commission, so would not introduce any legislation. [24]

Electoral boundaries

The number of electorate MPs is calculated in three steps. The less populated of New Zealand's two principal islands, the South Island, has a fixed quota of 16 seats. The number of seats for the North Island and the number of special reserved seats for Māori are then calculated in proportion to these. (The Māori electorates have their own special electoral roll; people of Māori descent may opt to enroll either on this roll or on the general roll, and the number of Māori seats is determined with reference to the number of adult Māori who opt for the Māori roll.)

The number of electorates is recalculated, and the boundaries of each redrawn so as to make them approximately equal in population within a tolerance of plus or minus 5%, after each quinquennial (five-year) census. After the 2001 census, there were 7 Māori electorates and 62 general electorates, or 69 electorates in total. There were therefore normally 51 list MPs. By a quirk of timing, the 2005 election was the first election since 1996 at which the electorates were not redrawn since the previous election. A census was held on 7 March 2006 and new electorate boundaries released on 25 September 2007, creating an additional electorate in the North Island.[25] For the election in 2011 there will be 63 general electorates, 7 Māori electorates and 50 list seats.

Representation statistics

The Gallagher Index is a measurement of how closely the proportions of votes cast for each party is reflected in the number of parliamentary seats gained by that party. The resultant disproportionality figure is a percentage – the lower the index, the better the match.[26]

| Election | Disproportionality[27] | Number of Parties in Parliament |

|---|---|---|

| 1946–1993 average | 11.10% | 2.4 |

| 1996 | 3.43% | 6 |

| 1999 | 2.97% | 7 |

| 2002 | 2.37% | 7 |

| 2005 | 1.13% | 8 |

| 2008 | 3.84% | 7 |

| 2011 | 2.38% | 8 |

Political parties

As of August 2013, there are 12 registered political parties in New Zealand.[28][29]

| Party Name | Short Name | Date of Registration | In Parliament |

|---|---|---|---|

| The New Zealand National Party | National Party | 2 December 1994 | Yes |

| New Zealand First Party | NZ First | 20 December 1994 | Yes |

| ACT New Zealand | The ACT Party | 17 February 1995 | Yes |

| New Zealand Labour Party | Labour Party | 17 February 1995 | Yes |

| New Zealand Democratic Party for Social Credit | Democrats for Social Credit | 10 August 1995 | No |

| Green Party of Aotearoa/New Zealand | Green Party | 17 August 1995 | Yes |

| Aotearoa Legalise Cannabis Party | The ALCP | 30 May 1996 | No |

| Libertarianz | – | 11 September 1996 | No |

| Māori Party | – | 9 July 2004 | Yes |

| Mana Movement | – | 24 June 2011 | Yes |

| Conservative Party of New Zealand | Conservative Party | 6 October 2011 | No |

| United Future New Zealand | United Future | 13 August 2013 | Yes |

See also

- Electoral reform in New Zealand

- History of voting in New Zealand

- Elections in New Zealand

- New Zealand Parliament

References

- ↑ New Zealand Electoral Commission. "Who can and can't enrol?". New Zealand Electoral Commission. Retrieved 4 September 2014.

- 1 2 The term of parliament

- ↑ Constitution review panel denies 'hidden agenda'

- ↑ Editorial: Four year term better for country

- ↑ Mace, William (2 March 2013). "Support from business for longer terms". Stuff.co.nz. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 Setting up the Maori seats – Maori and the vote

- 1 2 Change in the 20th century – Maori and the vote

- ↑ Wilson, James Oakley (1985) [First ed. published 1913]. New Zealand Parliamentary Record, 1840–1984 (4th ed.). Wellington: V.R. Ward, Govt. Printer. p. 138. OCLC 154283103.

- 1 2 3 The right to vote, New Zealand History Online

- ↑ The 2011 General Election

- ↑ Prisoners and the Right to Vote, NZ Council for Civil Liberties

- ↑ Inmate voting ban sorry waste of time, NZ Herald

- ↑ "Under the Influence". Electoral Commission. 15 February 2013. Retrieved 9 August 2013.

- 1 2 "Key dates in New Zealand electoral reform". Elections New Zealand. Retrieved 9 August 2013.

- ↑ James, Colin (14 June 2011). "John Key, modest constitutional innovator". Otago Daily Times. Retrieved 6 December 2011.

- ↑ "New Zealand Election Results". Electoral Commission. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ↑ "General elections 1853–2005 – dates & turnout". Elections New Zealand. Retrieved 9 August 2013.

- ↑ Electoral Commission Proposals Paper 13 August 2012, p 3.

- 1 2 3 Electoral Commission Proposals Paper 13 August 2012, p 9.

- ↑ http://www.newshub.co.nz/opinion/opinion-labour-hypocrisy-over-mount-roskill-dirty-deal-2016083011. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ "Report of the Electoral Commission on the review of the MMP voting system" (PDF). Electoral Commission. 29 October 2012. Retrieved 7 December 2012.

- ↑ "Electoral (Adjustment of Thresholds) Amendment Bill – Proposed members' bills". New Zealand Parliament. 20 November 2012. Retrieved 7 December 2012.

- ↑ "Electoral threshold bill drawn". Stuff/Fairfax. 14 November 2013.

- ↑ "Government rejects recommendations to change MMP systtem". New Zealand Herald. 14 May 2014.

- ↑ Trevett, Claire (26 September 2007). "Central North Island marginal". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 29 September 2011.

- ↑ Stephen Levine and Nigel S. Roberts, The Baubles of Office: The New Zealand General Election of 2005 (Wellington: Victoria University Press, 2007), pp.33–4 ISBN 978-0-86473-539-3

- ↑ Gallagher, Michael. "Election indices" (PDF). Retrieved 7 February 2015.

- ↑ http://www.elections.org.nz/parties-candidates/registered-political-parties-0/register-political-parties-0

- ↑ http://www.elections.org.nz/sites/default/files/bulk-upload/documents/5%20June%202013%20Currently%20registered.pdf

External links

- The MMP Voting System – Mixed Member Proportional

- Sainte-Laguë allocation formula

- Virtual Election Calculator