Fidaxomicin

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Dificid, Dificlir |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of administration | Oral |

| ATC code | A07AA12 (WHO) |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | Minimal systemic absorption[1] |

| Biological half-life | 11.7 ± 4.80 hours[1] |

| Excretion | Urine (<1%), faeces (92%)[1] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| Synonyms | Clostomicin B1, lipiarmicin, lipiarmycin, lipiarmycin A3, OPT 80, PAR 01, PAR 101, tiacumicin B |

| CAS Number |

873857-62-6 |

| PubChem (CID) | 11528171 |

| ChemSpider |

8209640 |

| UNII |

Z5N076G8YQ |

| KEGG |

D09394 |

| ChEBI |

CHEBI:68590 |

| ChEMBL |

CHEMBL1255800 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.220.590 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

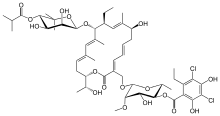

| Formula | C52H74Cl2O18 |

| Molar mass | 1058.04 g/mol |

| 3D model (Jmol) | Interactive image |

| |

| |

| | |

Fidaxomicin (trade names Dificid, Dificlir, and previously OPT-80 and PAR-101) is the first in a new class of narrow spectrum macrocyclic antibiotic drugs.[2] It is a fermentation product obtained from the actinomycete Dactylosporangium aurantiacum subspecies hamdenesis.[3][4] Fidaxomicin is non-systemic, meaning it is minimally absorbed into the bloodstream, it is bactericidal, and it has demonstrated selective eradication of pathogenic Clostridium difficile with minimal disruption to the multiple species of bacteria that make up the normal, healthy intestinal flora. The maintenance of normal physiological conditions in the colon can reduce the probability of Clostridium difficile infection recurrence.[5] [6]

It is marketed by Cubist Pharmaceuticals after acquisition of its originating company Optimer Pharmaceuticals. The target use is for treatment of Clostridium difficile infection.

Fidaxomicin is available in a 200 mg tablet that is administered every 12 hours for a recommended duration of 10 days. Total duration of therapy should be determined by the patient's clinical status. It is currently one of the most expensive antibiotics approved for use. A standard course costs upwards of £1350.[7]

Mechanism

Fidaxomicin binds to and prevents movement of the "switch regions" of bacterial RNA polymerase. Switch motion is important for opening and closing of the DNA:RNA clamp, a process that occurs throughout RNA transcription but especially during opening of double standed DNA during transcription initiation.[8] It has minimal systemic absorption and a narrow spectrum of activity; it is active against Gram positive bacteria especially clostridia. The minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) range for C. difficile (ATCC 700057) is 0.03–0.25 μg/mL.[3]

Clinical trials

Good results were reported by the company in 2009 from a North American phase III trial comparing it with oral vancomycin for the treatment of Clostridium difficile infection (CDI)[9][10] The study met its primary endpoint of clinical cure, showing that fidaxomicin was non-inferior to oral vancomycin (92.1% vs. 89.8%). In addition, the study met its secondary endpoint of recurrence: 13.3% of the subjects had a recurrence with fidaxomicin vs. 24.0% with oral vancomycin. The study also met its exploratory endpoint of global cure (77.7% for fidaxomicin vs. 67.1% for vancomycin).[11] Clinical cure was defined as patients requiring no further CDI therapy two days after completion of study medication. Global cure was defined as patients who were cured at the end of therapy and did not have a recurrence in the next four weeks.[12]

Fidaxomicin was shown to be as good as the current standard-of-care, vancomycin, for treating CDI in a Phase III trial published in February 2011.[13] The authors also reported significantly fewer recurrences of infection, a frequent problem with C. difficile, and similar drug side effects.

Approvals and indications

For the treatment of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea (CDAD), the drug won an FDA advisory panel's unanimous approval on April 5, 2011[14] and full FDA approval on May 27, 2011.[15]

References

- 1 2 3 "DIFICID" (PDF). TGA eBusiness Services. Specialised Therapeutics Australia Pty Ltd. 23 April 2013. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- ↑ Revill, P.; Serradell, N.; Bolós, J. (2006). "Tiacumicin B". Drugs of the Future. 31 (6): 494. doi:10.1358/dof.2006.031.06.1000709.

- 1 2 "Dificid, Full Prescribing Information" (PDF). Optimer Pharmaceuticals. 2013.

- ↑ "Fidaxomicin". Drugs in R&D. 10: 37. 2012. doi:10.2165/11537730-000000000-00000.

- ↑ Louie, T. J.; Emery, J.; Krulicki, W.; Byrne, B.; Mah, M. (2008). "OPT-80 Eliminates Clostridium difficile and is Sparing of Bacteroides Species during Treatment of C. Difficile Infection". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 53 (1): 261–3. doi:10.1128/AAC.01443-07. PMC 2612159

. PMID 18955523.

. PMID 18955523. - ↑ Johnson, Stuart (2009). "Recurrent Clostridium difficile infection: A review of risk factors, treatments, and outcomes". Journal of Infection. 58 (6): 403–10. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2009.03.010. PMID 19394704.

- ↑ http://www.medicinescomplete.com/mc/bnf/current/PHP18388-dificlir.htm#PHP18388-dificlir

- ↑ Srivastava, Aashish; Talaue, Meliza; Liu, Shuang; Degen, David; Ebright, Richard Y; Sineva, Elena; Chakraborty, Anirban; Druzhinin, Sergey Y; Chatterjee, Sujoy; Mukhopadhyay, Jayanta; Ebright, Yon W; Zozula, Alex; Shen, Juan; Sengupta, Sonali; Niedfeldt, Rui Rong; Xin, Cai; Kaneko, Takushi; Irschik, Herbert; Jansen, Rolf; Donadio, Stefano; Connell, Nancy; Ebright, Richard H (2011). "New target for inhibition of bacterial RNA polymerase: 'switch region'". Current Opinion in Microbiology. 14 (5): 532–43. doi:10.1016/j.mib.2011.07.030. PMC 3196380

. PMID 21862392.

. PMID 21862392. - ↑ "Optimer's North American phase 3 Fidaxomicin study results presented at the 49th ICAAC" (Press release). Optimer Pharmaceuticals. September 16, 2009. Retrieved May 7, 2013.

- ↑ "Optimer Pharmaceuticals Presents Results From Fidaxomicin Phase 3 Study for the Treatment" (Press release). Optimer Pharmaceuticals. May 17, 2009. Retrieved May 7, 2013.

- ↑ Golan Y, Mullane KM, Miller MA (September 12–15, 2009). Low recurrence rate among patients with C. difficile infection treated with fidaxomicin. 49th interscience conference on antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. San Francisco.

- ↑ Gorbach S, Weiss K, Sears P, et al. (September 12–15, 2009). Safety of fidaxomicin versus vancomycin in treatment of Clostridium difficile infection. 49th interscience conference on antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. San Francisco.

- ↑ Louie, Thomas J.; Miller, Mark A.; Mullane, Kathleen M.; Weiss, Karl; Lentnek, Arnold; Golan, Yoav; Gorbach, Sherwood; Sears, Pamela; Shue, Youe-Kong; Opt-80-003 Clinical Study, Group (2011). "Fidaxomicin versus vancomycin for Clostridium difficile infection". New England Journal of Medicine. 364 (5): 422–31. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0910812. PMID 21288078.

- ↑ Peterson, Molly (Apr 5, 2011). "Optimer wins FDA panel's backing for antibiotic fidaxomicin". Bloomberg.

- ↑ Nordqvist, Christian (27 May 2011). "Dificid (fidaxomicin) approved for Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea". Medical News Today.