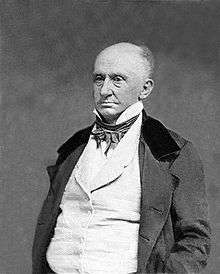

George Washington Parke Custis

| George Washington Parke Custis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

April 30, 1781 Rosaryville State Park |

| Died |

October 10, 1857 (aged 76) Virginia |

| Resting place | Arlington National Cemetery |

| Nationality | American |

| Education |

Germantown Academy Princeton University St John's College |

| Occupation | Author |

| Spouse(s) | Mary Lee Fitzhugh Custis |

| Parent(s) | John Parke Custis |

| Relatives |

George Washington (stepfather) Robert E. Lee (son-in-law) |

George Washington Parke Custis (April 30, 1781 – October 10, 1857) was the step-grandson and adopted son of United States President George Washington, the grandson of Martha Washington and the father-in-law of American Confederate Army general Robert E. Lee. He spent part of his large inherited fortune constructing Arlington House on a plantation in the present Arlington County, Virginia, that was directly across the Potomac River from Washington, D.C. After Custis died, his daughter, Mary Anna Randolph Custis, who had married Robert E. Lee, inherited his estate.

The United States government confiscated the Custis estate during the American Civil War. After the war ended, the Supreme Court of the United States rescinded the confiscation and returned the estate to George Washington Custis Lee, the son of Mary Anna Randolph Custis Lee and Robert E. Lee. George Washington Custis Lee then sold the estate back to the United States government.

Arlington House is now the Robert E. Lee Memorial. The remainder of the Arlington plantation is now Arlington National Cemetery and Fort Myer.

Custis purchased, preserved and displayed many of George Washington's belongings, wrote historical plays about Virginia, delivered a number of patriotic addresses, and wrote a memoir of his life in the Washington household.

Early life

George Washington Parke Custis (G.W.P. Custis) was born on April 30, 1781, at his mother's family home at Mount Airy, which is now a restored mansion in Rosaryville State Park in Prince George's County, Maryland.[1] He initially lived with his parents John Parke Custis (Jacky Custis) and Eleanor Calvert Custis, and his sisters Elizabeth Parke Custis, Martha Parke Custis and Nelly Custis, at the Abingdon Plantation (part of which is now the location of Ronald Reagan National Airport in Arlington County), which his father had purchased in 1778.[2] However, six months after G.W.P. Custis was born, his father died of "camp fever" at Yorktown, Virginia, shortly after the British army surrendered there.

Custis' grandmother, Martha Dandridge Custis Washington, had earlier married George Washington and had raised at Mount Vernon G.W.P Custis' father, John Parke Custis. After John Parke Custis died, George Washington adopted his namesake, G.W.P Custis, and with Martha Washington raised Custis and his sister, Nelly Custis, at Mount Vernon.[2][3][4] G.W.P. Custis' two oldest sisters, Elizabeth and Martha, remained at Abingdon with their widowed mother, who in 1783 married Dr. David Stuart, an Alexandria physician and associate of George Washington.[5]

"The Washington Family" by Edward Savage, painted between 1789 and 1796, shows (from left to right): George Washington Parke Custis, George Washington, Nelly Custis, Martha Washington, and an enslaved servant (probably William Lee or Christopher Sheels).

The Washingtons brought George and Nelly, 8 and 10 years old, respectively, to New York City in 1789 to live in the first and second presidential mansions. Following the transfer of the national capital to Philadelphia, the original "First Family" occupied the President's House from 1790 to 1797.

G.W.P. Custis (nicknamed "Wash") attended (but did not graduate from) the Germantown Academy in Germantown (now in Philadelphia), Pennsylvania, the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University) and St. John's College in Annapolis, Maryland. George Washington repeatedly expressed frustration about young Custis, as well as his own inability to improve the youth's attitude. Upon young Custis' return to Mount Vernon after only one term at St. John's, George Washington sent him to his mother and stepfather (Dr. David Stuart) at Hope Park, writing "He appears to me to be moped and Stupid, says nothing, and is always in some hole or corner excluded from the Company."[6]

Career

In January 1799, Custis was commissioned as a cornet in the United States Army and was promoted to second Lieutenant in March. He served as aide-de-camp to General Charles Cotesworth Pinckney and was honorably discharged 15 June 1800.[7]

When G.W.P. Custis came of age, he inherited large amounts of money, land and property from the estates of his father (John Parke Custis) and grandfather (Daniel Parke Custis). Upon Martha Washington's death in 1802, he received a bequest from her (as he had upon George Washington's death in 1799) as well as his father's former plantations because of the termination of her life estate.[8] However, her executor, Bushrod Washington, refused to sell to G.W.P. Custis the Mt. Vernon estate on which Custis had been living and which Bushrod Washington (George Washington's nephew) had inherited. Custis thereupon moved into the four-room, 80-year-old house on land inherited from his father, who had called it "Mount Washington."[9]

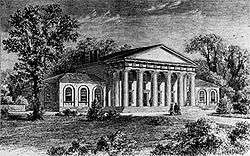

Almost immediately, G.W.P. Custis began constructing Arlington House on his land, which at the time was within Alexandria County (now Arlington County) in the District of Columbia. Hiring George Hadfield as architect, he constructed a mansion exhibiting the first example of Greek Revival architecture in America.[10] He located the building on a prominent hill overlooking the Georgetown-Alexandria Turnpike (at the approximate location of the present Eisenhower Drive in Arlington National Cemetery), the Potomac River and the growing Washington City on the opposite side of the river.[10]

Using slave labor and materials on site, and interrupted by the War of 1812 (and material shortages after the British burned the American capital city), G.W.P. Custis finally completed the mansion's exterior in 1818.[11] Custis intended the mansion to serve as a living memorial to George Washington, and included design elements similar to Mt. Vernon.[12] He then gained a reputation for inviting many guests for various celebrations and social events at the mansion, where he also displayed relics from Mt. Vernon, although the interior was not completed (and renovated) until occupancy by Robert E. Lee's family (including Custis' grandsons/heirs) in the 1850s.[13][14]

During the War of 1812, Custis assisted in the firing of an artillery piece to help defend Washington, D.C. from the British during the Battle of Bladensburg.[15] He also delivered and published an address condemning the death of Revolutionary War General James Lingan who was killed by a Baltimore mob for defending an anti-war publisher's right to oppose the war.[16][17]

Custis was elected a member of the American Antiquarian Society in 1815.[18]

One biographer claimed Lafayette and his son Georges Washington de La Fayette visited Custis at Mount Vernon in 1825, although Custis was then living at Arlington House.[19]

During the 1820s, Custis was an active member of the American Colonization Society, an organization that supported the colonization of free blacks in Africa, particularly in Liberia. Colonization was unpopular with African American slaves. Of the Arlington slaves, only William Burke and his family chose to move to Liberia. Custis lost interest in the Society, but his wife and daughter continued to support it for many years. In 1854, William and Rosabella Burke and their children left Arlington House for Monrovia, Liberia, with their children. Rosabella continued to write to Mrs. Lee and named a new daughter "Martha" in tribute to the family.[20]

In 1846, the federal government retroceded to the state of Virginia the portion of the District of Columbia that was south and west of the Potomac River, which at the time contained the city and county of Alexandria (see District of Columbia retrocession). G.WP. Custis initially opposed the retrocession, but later spoke in support of it. Alexandrians then elected Custis to represent the area before the Virginia General Assembly when the legislature considered the retrocession. The General Assembly approved the retrocession on March 13, 1847.[21]

On July 4, 1848, Custis attended the ceremony that celebrated the laying of the cornerstone of the Washington Monument by Freemasons. Supervised by President James K. Polk. the ceremony also attracted 20,000 other spectators.[22] On July 4, 1850, Custis dedicated a stone that the people of the District of Columbia had donated to the Monument at a ceremony that President Zachary Taylor attended, five days before Taylor died from food poisoning.[23]

In 1853, the writer Benson John Lossing visited Custis at Arlington House.[24]

Custis achieved some distinction as an orator and playwright. In addition to the Lingam eulogy, he delivered The Celebration of the Russian Victories, in Georgetown, District of Columbia; on the 5th of June, 1813 (1813). Two of Custis's plays, The Indian Prophecy; or Visions of Glory (1827) and Pocahontas; or, The Settlers of Virginia (1830), were published during his lifetime. Other plays included The Rail Road (1828), The Eighth of January, or, Hurra for the Boys of the West! (ca. 1830), North Point, or, Baltimore Defended (1833), and Montgomerie, or, The Orphan of a Wreck (1836). Custis wrote a series of biographical essays about his adoptive father that were compiled and published in 1859 and 1860 as Recollections and Private Memoirs of Washington after his death in 1857.[25]

Family ties

G.W.P. Custis descended from a number of aristocratic colonial era families, as well as, through his mother, the British nobility and, very distantly, from the royal House of Hanover and the House of Stuart. His mother, Eleanor Calvert Custis Stuart, descended from Charles Calvert, 3rd Baron Baltimore, and Henry Lee of Ditchley, one of whose descendants was Edward Lee, first Earl of Litchfield, who married Lady Charlotte Fitzroy, an illegitimate daughter of Charles II by one of his mistresses, Barbara Palmer, Duchess of Cleveland. It is believed he is descended from George I by his natural daughter Melusina von der Schulenburg, Countess of Walsingham, whose extra-marital liaison with the 5th Baron Baltimore produced a son, Benedict Swingate Calvert, his maternal grandfather. His father, John Parke Custis, was the son of Martha Washington through her marriage to Daniel Parke Custis.

Custis' sister, Eleanor Parke Custis Lewis (Nelly Custis) married George Washington's nephew, Lawrence Lewis. As a wedding present, Washington gave Nelly a section of Mount Vernon's land, on which the Lewises established the Woodlawn plantation and constructed the Woodlawn Mansion.[26] The National Park Service has listed Woodlawn on the National Register of Historic Places.[26]

Another sister of G. W. P. Custis, Martha Parke Custis Peter (Martha Custis) married Thomas Peter. Using Martha's inheritances from George and Martha Washington the Peters purchased property in Georgetown within the District of Columbia. The couple then constructed the Tudor Place mansion on the property. Tudor Place and its grounds, which the National Park Service has listed on the National Register of Historic Places, contain features that resemble those of Arlington House and Woodlawn.[27]

On July 7, 1804, Custis married Mary Lee Fitzhugh. Of their four children, only one daughter, Mary Anna Randolph Custis, survived to maturity. She married Robert E. Lee at Arlington House on June 30, 1831. Lee's father, Henry Lee III (Light-Horse Harry Lee) had earlier eulogized George Washington at Washington's December 18, 1799, funeral.[28]

In 1826, Custis admitted paternity of Maria Carter, who had been born in 1803 to Arianna (Airy) Carter (1776-1880), an African American slave maid at the Arlington estate who had earlier resided at Mount Vernon as a slave of Martha Washington. Maria lived and worked at Arlington as a slave until 1826, when she married Charles Syphax, a slave who oversaw the dining room of Arlington House. Soon after Maria's marriage, Custis freed her and gave her a 17-acre (7-hectare) plot in the southwest corner of the Arlington estate. Maria subsequently raised ten children on her property. Tall trees and stretches of grassland reportedly surrounded Maria's white cottage.[20][29] He is also believed to have fathered a girl named Lucy with the slave Caroline Branham.[30]

Legacy

Custis died in 1857 and was buried at Arlington alongside his wife, Mary Lee Fitzhugh Custis, who had died four years earlier.[31] Custis's will[32] provided that:

- Arlington plantation (approx. 1100 acres) and its contents, including Custis's collection of George Washington's artifacts and memorabilia, would be bequeathed to his only surviving child, Mary Anna Randolph Custis (wife of Robert E. Lee) for her natural life, and upon her death, to his eldest grandson George Washington Custis Lee;

- White House plantation in New Kent County and Romancoke plantation in King William County (approx. 4000 acres each) would be bequeathed to his other two grandsons William Henry Fitzhugh Lee ("Rooney Lee") and Robert Edward Lee, Jr., respectively;

- Legacies (cash gifts) of $10,000 each would be provided to his four granddaughters, based on the incomes from the plantations and the sales of other smaller properties; (Some properties could not be sold until after the Civil War and it was doubtful that $10,000 each was ever fully paid.)

- Certain property in "square No. 21, Washington City" (possibly located between present day Foggy Bottom and Potomac River)[33] to be bequeathed to Robert E. Lee "and his heirs."

- Custis's slaves, numbered around 200, were to be freed once the legacies and debts from his estate were paid, but no later than five years after his death.[34]

Custis' death influenced the careers of Robert E. Lee and his two elder sons on the cusp of the American Civil War.[35] Then-Lt. Col. Robert E. Lee, named as the will's executor, took leave from his Army post in Texas for two years to settle the estate. During this period Lee was ordered to lead troops to quash John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry. By 1859, Lee's eldest son, George Washington Custis Lee, transferred to an Army position in Washington, D.C. so that he could care for Arlington plantation, where his mother and sisters were living. Lee's second son, Rooney Lee, resigned his army commission, got married, and took over farming White House and Romancoke plantations near Richmond. Robert E. Lee was able to leave for Texas to resume his Army career in February 1860.[36]

At the outbreak of the American Civil War, Union Army forces seized the 1,100-acre (4.5 km2) Arlington Plantation for strategic reasons (protection of the river and national capital).[37] The United States government then confiscated the Custis estate for non-payment of taxes.[37] In 1863, a "Freedman's Village" was established there for freed slaves.[37][38][39]

In 1864, Montgomery C. Meigs, Quartermaster General of the US Army, appropriated some parts of Arlington Plantation for use as a military burial ground.[37][40] After the Civil War ended, George Washington Custis Lee sued and recovered the title for the Arlington Plantation from the United States government in 1882, when the Supreme Court of the United States ruled in favor of Lee in United States v. Lee, 106 U. S. 196.[37][41] Lee then sold the property back to the United State government for $150,000.[37] Arlington House, built by Custis to honor George Washington, is now the Robert E. Lee Memorial. It is restored and open to the public under the auspices of the National Park Service, while the Department of Defense controls Fort Myer and Arlington National Cemetery on the remainder of the Arlington Plantation.

| Ancestors of George Washington Parke Custis | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

- Samuel Osgood House (New York City) — First Presidential Mansion.

- Alexander Macomb House (New York City) — Second Presidential Mansion.

- President's House (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) — Third Presidential Mansion.

Notes

- ↑ Maryland Historical Society. "Mount Airy marker". in Robby, F (2008-06-17). "Mount Airy". The Historical Marker Database.

- 1 2 Templeman, Eleanor Lee (1959). Arlington Heritage: Vignettes of a Virginia County. New York: Avenel Books, a division of Crown Publishers, Inc. pp. 12–13.

- ↑ Kail, Wendy (2009). "Martha Parke Custis Peter". gwpapers.virginia.edu, The Papers of George Washington. University of Virginia Library: Alderman Library. Retrieved 2011-05-06.

- ↑ Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority. ""The Custis Family" marker". in W., Kevin, Stafford, Virginia (2008-06-17). "The Custis Family: Abingdon Plantation". The Historical Marker Database. Retrieved 2011-03-18.

- ↑ The Stuarts subsequently had 16 children while living at Abingdon, Hope Park and Ossian Hall in Northern Virginia. Johnson, R. Winder (1905). The Ancestry of Rosalie Morris Johnson: Daughter of George Calvert Morris and Elizabeth Kuhn, his wife. Ferris & Leach. p. 30. Retrieved 2011-05-20.

- ↑ Washington, George (1798-08-13). John C. Fitzpatrick, ed. To David Stuart. The Writings of George Washington from the Original Manuscript Sources 1745-1799: Volume 36: August 4, 1797-October 28, 1798: Prepared under the direction of the United States George Washington Bicentennial Commission and published by authority of Congress,1939-01-01. Best Books. p. 412. ISBN 9781623764463. At Google Books.

- ↑ http://www.arlingtoncemetery.net/gwpcusti.htm

- ↑ These included about 80 slaves from the John Parke Custis estate; 35 dower slaves at Mount Vernon from the Daniel Parke Custis estate; Elisha, the one slave Martha Washington owned outright; and about 40 more slaves from the John Parke Custis estate following his mother's 1811 death. See: Henry Weincek, An Imperfect God: George Washington, His Slaves, and the Creation of America (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2003), p. 383n. See also: Slavery by the Numbers

- ↑ Rudy, p. 15.

- 1 2 Smith, Adam; Tooker, Megan; Enscore, Susan (U.S. Corps of Engineers) (2013-01-31). "National Register of Historic Places Registration Form: Arlington National Cemetery Historic District" (PDF). United States Department of the Interior: National Park Service. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-09-04. Retrieved 2016-09-03.

- ↑ Rudy, pp. 16-18, 35-36.

- ↑ Rudy, pp. 9, 31.

- ↑ Rudy, p. 37.

- ↑ http://www.nps.gov/arho/historyculture/george-custis.htm

- ↑ McCavitt, John; George, Christopher (2016). Battle of Bladensburg, August 24,1814. The man who captured Washington: Major General Robert Ross and the War of 1812. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. p. 137. ISBN 9780806151649. OCLC 911518963.

A Mr. Custis of Arlington, a relative of George Washington, assisted in loading the last round, despite being disabled in one hand by rheumatism.

At Google Books. - ↑ Oration by Mr. Custis, of Arlington; with an Account of the Funeral Solemnities in Honor of the Lamented Gen. James M. Lingan (1812) at http://webapp1.dlib.indiana.edu/metsnav/common/navigate.do?oid=VAC2386&pn=4&size=screen

- ↑ http://articles.baltimoresun.com/1996-05-24/features/1996145064_1_lingan-mob-revolutionary-war

- ↑ American Antiquarian Society Members Directory

- ↑ Auguste Levasseur. Lafayette in America. Translator Alan Hoffman. pp. 197–9.

- 1 2 "The Women of Arlington". arlingtonhouse.org. Save Historic Arlington House, Inc. 2012. Archived from the original on 2015-11-16. Retrieved 2015-11-16.

- ↑ Richards, Mark David. "The Debates over the Retrocession of the District of Columbia, 1801–2004" (PDF). Washington History: Magazine of the Historical Society of Washington, D.C. Washington, D.C. 16 (1, Spring/Summer 2004): 67–68. ISSN 1042-9719. OCLC 429216416. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-02-19. Retrieved 2016-09-03. At DC Vote.

- ↑ Crutchfield, James A. (2005). George Washington: First in War, First in Peace. New York, N.Y.: A Forge Book: Tom Doherty Associates, LLC. p. 218. ISBN 0765310708. OCLC 269434694. At Google Books.

- ↑ Perry, John (2010). Lee: A Life of Virtue. Nashville, Tennessee: Thomas Nelson. pp. 93–94. ISBN 1595550283. OCLC 456177249. At Google Books.

- ↑ See the Cornell University Library transcription of Harper's New Monthly Magazine article: (starting on page 433). Four of the Custis paintings mentioned in the Harper's article(Battle of Germantown/Battle of Trenton/Battle of Princeton/Washington at Yorktown) were republished in American Heritage magazine in February 1966.

- ↑ (1) Custis, G.W. Parke of Arlington (1859). Recollection and Private Memoirs of Washington: Compiled from files of the National Intelligencer, printed at Washington, D.C. Washington, D.C.: William H. Moore (printer). OCLC 1348198. At Google Books.

(2) Lee, Mary Custis (1860). Recollection and Private Memoirs of Washington, by his adopted son, George Washington Parke Custis, with a memoir by his daughter; and explanatory and explanatory notes by Benson J. Lossing. New York: Derby & Jackson. ISBN 1143944348. At Google Books. - 1 2 Tuminaro, Craig; Pitts, Carolyn (March 4, 1998). "National Historic Landmark Nomination Form: Woodlawn" (PDF). National Park Service. Archived from the original (pdf) on 2015-11-18.

- ↑ Morton, W. Brown, III (1971-02-08). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination Form: Tudor Place" (PDF). National Park Service. Archived from the original (pdf) on 2012-10-05. Retrieved 2015-11-19.

- ↑ "Papers of George Washington". Gwpapers.virginia.edu. Retrieved 2012-05-14.

- ↑ (1) "Maria Carter Syphax". Museum Management Program. Arlington House: The Robert E. Lee Memorial: Virtual Museum Exhibit: National Park Service. Archived from the original on 2015-11-16. Retrieved 2015-11-16.

(2) Clark, Charlie (2015-11-16). "Our Man in Arlington". Falls Church, Virginia: Falls Church News-Press. Archived from the original on 2015-11-16. Retrieved 2015-11-16. - ↑ Baracat, Matthew (2016-09-19). "Historic recognition: Washington's family tree is biracial". Fairfield Citizen. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 2016-09-23. Retrieved 2016-09-23.

- ↑ "George Washington Parke Custis". Michael Robert Patterson. Retrieved 2012-10-07.

- ↑ "Will of George Washington Parke Custis". Nathanielturner.com. Retrieved 2012-05-14.

- ↑ http://www.history-map.com/picture/005/pictures/Washington-Map-Old-001.jpg

- ↑ Fulfilled by Robert E. Lee, executor, in the winter of 1862. see http://files.usgwarchives.net/va/spotsylvania/wills/c2320001.txt

- ↑ Freeman, Douglas Southall (1934). "Chapter 22". Robert E. Lee: a Biography. vol. 1. Scribner.

- ↑ Freeman. "Chapter 23". Robert E. Lee. vol. 1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Arlington House, The Robert E. Lee Memorial". Arlington National Cemetery. Arlington, Virginia: United States Army. 2015-10-07. Archived from the original on 2016-01-17. Retrieved 2016-09-28.

- ↑ Schildt, Roberta (1984). "Freedmen's Village: Arlington, Virginia, 1863-1900" (PDF). Arlington Historical Magazine. Arlington County, Virginia: Arlington Historical Society, Inc. 7 (4): 11–21. Retrieved 2016-09-28. At arlcivilwar.net: Arlington's Civil War Memorial Website

- ↑ "Black History at Arlington National Cemetery". Arlington National Cemetery. Arlington, Virginia: United States Army. Archived from the original on 2016-01-23. Retrieved 2016-09-28.

- ↑ "The Beginnings of Arlington National Cemetery". Arlington House, The Robert E. Lee Memorial. National Park Service: United States Department of the Interior. 2016. Archived from the original on 2016-08-27. Retrieved 2016-09-28.

- ↑

United States v. Lee Kaufman. Wikisource.

United States v. Lee Kaufman. Wikisource.

References

- Bearss, Sara B. "The Federalist Career of George Washington Parke Custis", Northern Virginia Heritage 8 (February 1986): 15–20.

- Bearss, Sara B. "The Farmer of Arlington: George W. P. Custis and the Arlington Sheep Shearings", Virginia Cavalcade 38 (1989): 124–133.

- Brady, Patricia. Martha Washington: An American Life (New York: Viking/Penguin, 2005). ISBN 0-670-03430-4.

- John T. Kneebone et al., eds., Dictionary of Virginia Biography (Richmond: The Library of Virginia, 1998- ), 3:630-633. ISBN 0-88490-206-4.

- Ribblett, David L. "Nelly Custis: Child of Mount Vernon" (The Mount Vernon Ladies Association, 1993)41-42. ISBN 0-931917-23-9.

- Rudy, William George (2010). Interpreting America's First Grecian Style House: the Architectural Legacy of George Washington Parke Custis and George Hadfield (PDF). Masters Thesis. College Park, Maryland: University of Maryland. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-07. Retrieved 2016-09-03.

External links

- Biography by the National Park Service

- Biography and epitaph

- Custis's Will

- The President's House in Philadelphia

- George Washington Parke Custis at Find a Grave