Hiram Rhodes Revels

| The Reverend Hiram Rhodes Revels | |

|---|---|

.png) | |

| United States Senator from Mississippi | |

|

In office February 23, 1870 – March 3, 1871 | |

| Preceded by | Albert G. Brown |

| Succeeded by | James L. Alcorn |

| Member of the Mississippi Senate | |

|

In office 1869–1875 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

September 27, 1827[note 1] Fayetteville, North Carolina, U.S. |

| Died |

January 16, 1901 (aged 73) Aberdeen, Mississippi, U.S. |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse(s) | Phoebe A. Bass Revels |

| Alma mater | Knox College |

| Profession | Politician, Barber, Minister, College President |

| Religion | African Methodist Episcopal Church |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance |

|

| Service/branch |

|

| Years of service | 1863–1865 |

| Unit | Chaplain Corps |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War |

Hiram Rhodes Revels (September 27, 1827[note 1] – January 16, 1901) was a minister in the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME), a Republican politician, and college administrator. Born free in North Carolina, he later lived and worked in Ohio, where he voted before the Civil War. He became the first African American to serve in the U.S. Congress when he was elected to the United States Senate to represent Mississippi in 1870 and 1871 during the Reconstruction era.

During the American Civil War, Revels had helped organize two regiments of the United States Colored Troops and served as a chaplain. After serving in the Senate, Revels was appointed as the first president of Alcorn Agricultural and Mechanical College (now Alcorn State University), 1871-1873 and 1876 to 1882. Later he served again as a minister.

Early life and education

Revels was born free in Fayetteville, North Carolina, to free people of color, parents of African and European ancestry. He was tutored by a black woman for his early education. In 1838 he went to live with his older brother, Elias B. Revels, in Lincolnton, North Carolina, and was apprenticed as a barber in his brother's shop. After Elias Revels died in 1841, his widow Mary transferred the shop to Hiram before she remarried. Revels attended the Union County Quaker Seminary in Indiana, and Darke County Seminary in Ohio.[1] He was a second cousin to Lewis Sheridan Leary, one of the men who was killed taking part in John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry and to North Carolina lawyer and politician John S. Leary.[2]

In 1845 Revels was ordained as a minister in the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME); he served as a preacher and religious teacher throughout the Midwest: in Indiana, Illinois, Ohio, Tennessee, Missouri, and Kansas.[1] "At times, I met with a great deal of opposition," he later recalled. "I was imprisoned in Missouri in 1854 for preaching the gospel to Negroes, though I was never subjected to violence."[3] During these years, he voted in Ohio.

He studied religion from 1855 to 1857 at Knox College in Galesburg, Illinois. He became a minister in a Methodist Episcopal Church in Baltimore, Maryland, where he also served as a principal for a black high school.[4]

As a chaplain in the United States Army, Revels helped recruit and organize two black Union regiments during the Civil War in Maryland and Missouri. He took part at the battle of Vicksburg in Mississippi.[5]

Political career

In 1865, Revels left the AME Church and joined the Methodist Episcopal Church. He was assigned briefly to churches in Leavenworth, Kansas, and New Orleans, Louisiana. In 1866, he was called as a permanent pastor at a church in Natchez, Mississippi, where he settled with his wife and five daughters. He became an elder in the Mississippi District of the Methodist Church,[4] continued his ministerial work, and founded schools for black children.

During Reconstruction, Revels was elected alderman in Natchez in 1868. In 1869 he was elected to represent Adams County in the Mississippi State Senate. As the Congressman John R. Lynch later wrote of him in his book on Reconstruction:

Revels was comparatively a new man in the community. He had recently been stationed at Natchez as pastor in charge of the A.M.E. Church, and so far as known he had never voted, had never attended a political meeting, and of course, had never made a political speech. But he was a colored man, and presumed to be a Republican, and believed to be a man of ability and considerably above the average in point of intelligence; just the man, it was thought, the Rev. Noah Buchanan would be willing to vote for.[6]

In January 1870, Revels presented the opening prayer in the state legislature. Lynch wrote,

"That prayer—one of the most impressive and eloquent prayers that had ever been delivered in the [Mississippi] Senate Chamber—made Revels a United States Senator. He made a profound impression upon all who heard him. It impressed those who heard it that Revels was not only a man of great natural ability but that he was also a man of superior attainments."[6]

Election to Senate

At the time, as in most states, the state legislature elected U.S. senators from the state. In 1870 Revels was elected by a vote of 81 to 15 in the Mississippi State Senate to finish the term of one of the state's two seats in the US Senate, which had been left vacant since the Civil War. Previously, it had been held by Albert G. Brown, who withdrew from the US Senate in 1861 when Mississippi seceded.[7]

When Revels arrived in Washington, D.C., southern Democrats opposed seating him in the Senate. For the two days of debate, the Senate galleries were packed with spectators at this historic event.[8] The Democrats based their opposition on the 1857 Dred Scott Decision by the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled that people of African ancestry were not and could not be citizens. They argued that no black man was a citizen before the 14th Amendment was ratified in 1868, and thus Revels could not satisfy the requirement of the Senate for nine years' prior citizenship.[9]

Supporters of Revels made a number of arguments, from the relatively narrow and technical to fundamental arguments about the meaning of the Civil War. Among the narrower arguments was that Revels was of primarily European ancestry (an "octoroon") and that the Dred Scott Decision ought to be read to apply only to those blacks who were of totally African ancestry. Supporters argued that Revels had long been a citizen (and had voted in Ohio) and that he had met the nine-year requirement before the Dred Scott decision changed the rules and held that blacks could not be citizens.[10]

The more fundamental arguments by Revels supporters boiled down to this idea: that the Civil War, and the Reconstruction Amendments, had overturned Dred Scott. The meaning of the war, and also of the Amendments, was that the subordination of the black race was no longer part of the American constitutional regime, and that therefore, it would be unconstitutional to bar Revels on the basis of the pre-Civil War Constitution's racist citizenship rules.[10] One Republican Senator supporting Revels mocked opponents as still fighting the "last battle-field" of that War.[10]

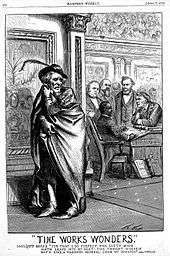

Massachusetts senator Charles Sumner said, "The time has passed for argument. Nothing more need be said. For a long time it has been clear that colored persons must be senators."[9] On February 25, 1870, Revels, on a strict party-line vote of 48 to 8, with only Republicans voting in favor and only Democrats voting against, became the first African American to be seated in the United States Senate.[9] Everyone in the galleries stood to see him sworn in.[8]

Sumner's Massachusetts colleague, Henry Wilson, defended Revels's election,[11] and presented as evidence of its validity signatures from the clerks of the Mississippi House of Representatives and Mississippi State Senate, as well as that of Adelbert Ames, the military Governor of Mississippi.[12] Wilson argued that Revels's skin color was not a bar to Senate service, and connected the role of the Senate to Christianity's Golden Rule of doing to others as one would have done to oneself.[12] The Senate voted to seat Revels, and after he took the oath of office Wilson personally escorted him to his desk as journalists recorded the historic event.[12]

U.S. Senator

Revels advocated compromise and moderation. He vigorously supported racial equality and worked to reassure his fellow senators about the capability of African Americans. In his maiden speech to the Senate on March 16, 1870, he argued for the reinstatement of the black legislators of the Georgia General Assembly, who had been illegally ousted by white Democratic Party representatives. He said, "I maintain that the past record of my race is a true index of the feelings which today animate them. They aim not to elevate themselves by sacrificing one single interest of their white fellow citizens."[13]

He served on both the Committee of Education and Labor and the Committee on the District of Columbia. (At the time, the Congress administered the District.) Much of the Senate's attention focused on Reconstruction issues. While Radical Republicans called for continued punishment of ex-Confederates, Revels argued for amnesty and a restoration of full citizenship, provided they swore an oath of loyalty to the United States.[14]

Revels' term lasted one year, February 1870 to March 3, 1871. He quietly, persistently—although for the most part unsuccessfully—worked for equality. He spoke against an amendment proposed by Senator Allen G. Thurman (D-Ohio) to keep the schools of Washington, D.C., segregated. He nominated a young black man to the United States Military Academy; the youth was subsequently denied admission. Revels successfully championed the cause of black workers who had been barred by their color from working at the Washington Navy Yard.

The northern press praised Revels for his oratorical abilities. His conduct in the Senate, along with that of the other black Americans who had been seated in the House of Representatives, prompted a white Congressman, James G. Blaine, to write in his memoir, "The colored men who took their seats in both Senate and House were as a rule studious, earnest, ambitious men, whose public conduct would be honorable to any race."[15] Revels supported bills to invest in developing infrastructure in Mississippi: to grant lands and right of way to aid the construction of the New Orleans and Northeastern Railroad (41st Congress 2nd Session S. 712), and levees on the Mississippi river (41st Congress 3rd Session S. 1136).[9] He argued for integration of schools in the District of Columbia.[4]

College president

Revels accepted in 1871, after his term as U.S. Senator expired, appointment as the first president of Alcorn Agricultural and Mechanical College (now Alcorn State University), a historically black college located in Claiborne County, Mississippi. He taught philosophy as well. In 1873, Revels took a leave of absence from Alcorn to serve as Mississippi's secretary of state ad interim. He was dismissed from Alcorn in 1874 when he campaigned against the reelection of Governor of Mississippi Adelbert Ames. He was reappointed in 1876 by the new Democratic administration and served until his retirement in 1882[14]

On November 6, 1875, Revels, as a Republican, wrote a letter to Republican President Ulysses S. Grant that was widely reprinted. Revels denounced Ames and the carpetbaggers for manipulating the black vote for personal benefit, and for keeping alive wartime hatreds:[16]

Since reconstruction, the masses of my people have been, as it were, enslaved in mind by unprincipled adventurers, who, caring nothing for country, were willing to stoop to anything no matter how infamous, to secure power to themselves, and perpetuate it..... My people have been told by these schemers, when men have been placed on the ticket who were notoriously corrupt and dishonest, that they must vote for them; that the salvation of the party depended upon it; that the man who scratched a ticket was not a Republican. This is only one of the many means these unprincipled demagogues have devised to perpetuate the intellectual bondage of my people.... The bitterness and hate created by the late civil strife has, in my opinion, been obliterated in this state, except perhaps in some localities, and would have long since been entirely obliterated, were it not for some unprincipled men who would keep alive the bitterness of the past, and inculcate a hatred between the races, in order that they may aggrandize themselves by office, and its emoluments, to control my people, the effect of which is to degrade them.

Revels remained active as a Methodist Episcopal minister in Holly Springs, Mississippi and became an elder in the Upper Mississippi District.[4] For a time, he served as editor of the Southwestern Christian Advocate, the newspaper of the Methodist Church. He taught theology at Shaw College (now Rust College), a historically black college founded in 1866 in Holly Springs. Hiram Revels died on January 16, 1901, while attending a church conference in Aberdeen, Mississippi. He was buried at the Hillcrest Cemetery in Holly Springs, Mississippi.[17]

Legacy

Revels' daughter Susan Revels edited a newspaper in Seattle, Washington. Among his grandsons were Horace R. Cayton, Jr., co-author of Black Metropolis, and Revels Cayton, a labor leader.[18] In 2002, scholar Molefi Kete Asante listed Hiram Rhodes Revels as one of 100 Greatest African Americans.[19]

Notes

References

- Citations

- 1 2

- United States Congress. "Hiram Rhodes Revels (id: R000166)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- ↑ Oates, John Alexander. The story of Fayetteville and the Upper Cape fear. Dowd Press, 1950. p714

- ↑ Aaseng, Nathan. African-American Religious Leaders: A-Z of African Americans. Infobase Publishing, 14 May 2014. p 189-191

- 1 2 3 4 "Hiram Rhodes Revels", Robinson Library, 2011, accessed 17 October 2014

- ↑ U.S. Senate: Art & History Home > Photo Exhibit at www.senate.gov

- 1 2 John R. Lynch. “Chapter III”, The Facts of Reconstruction. Retrieved on 2012-11-01 at Project Gutenberg

- ↑ "BROWN, Albert Gallatin - Biographical Information". U.S. Congress. Retrieved July 25, 2012.

- 1 2 "The Colored Member Admitted to His Seat in the Senate", New York Times, 25 February 1870, accessed 10 October 2012

- 1 2 3 4 "First African American Senator". U.S. Senate. Retrieved July 25, 2012.

- 1 2 3 Richard Primus, "The Riddle of Hiram Revels", 119 Harvard Law Review 1680 (2006)

- ↑ Myers, John L. (2009). Henry Wilson and the Era of Reconstruction. Lanham, MD: University Press of America, Inc. p. 129. ISBN 0-7618-4742-1.

- 1 2 3 Myers 2009, p. 129

- ↑ Ploski 18.

- 1 2 REVELS, Hiram Rhodes. History, Art & Archives, United States House of Representatives. http://history.house.gov/People/Listing/R/REVELS,-Hiram-Rhodes-(R000166)/

- ↑ Blaine, Twenty Years in Congress

- ↑ full text in James Wilford Garner. Reconstruction in Mississippi (1901) pp. 399-400.

- ↑ "Browse by Cemetery: Hill Crest Cemetery". Find a Grave. Retrieved September 12, 2015.

- ↑ Foner, Eric. Freedom's Lawmakers: A Directory of Black Officeholders during Reconstruction. 1996. Revised. ISBN 0-8071-2082-0. p. 181.

- ↑ Asante, Molefi Kete (2002). 100 Greatest African Americans: A Biographical Encyclopedia. Amherst, New York. Prometheus Books. ISBN 1-57392-963-8.

- Primary source

- Borome, Joseph A. "The Autobiography of Hiram Rhodes Revels Together with Some Letters by and about Him," Midwest Journal, 5 (Winter 1952-1953), pp. 79–92.

- Lynch, John R. The Facts of Reconstruction (1913), Online at Project Gutenberg - Memoir by Mississippi Congressman (a freedman) who served during Reconstruction

- Other references

- Foner, Eric. Freedom's Lawmakers: A Directory of Black Officeholders during Reconstruction. 1996. Revised. ISBN 0-8071-2082-0.

- Gravely, William B., "Hiram Revels Protests Racial Separation in the Methodist Episcopal Church (1876)," Methodist History, 8 (1970), pp. 13–20.

- Harris, William C., The Day of the Carpetbagger: Republican Reconstruction in Mississippi, Louisiana State University Press, 1979

- Haskins, James, Distinguished African American Political and Governmental Leaders, Oryx Press. 1999. pp: 216-8.

- Hildebrand, Reginald F., The Times Were Strange and Stirring: Methodist Preachers and the Crisis of Emancipation, Duke University Press, 1995

- Thompson, Julius E., Hiram Revels: A Biography (1973) (unpublished dissertation, Princeton University)

- State Library of North Carolina

- Clergy Politicians in Mississippi

- Biographical sketch at the U.S. Senate website

- Portrait and biography, Harper's Weekly, 19 February 1870, p. 116

- "The Colored Member Admitted to His Seat in the Senate", New York Times, 25 February 1870

- "Hiram Revels pioneered southern Black politics". African American Registry. Media Business Solutions. Archived from the original on 2003-05-06. Retrieved 2012-11-01.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hiram Revels. |

- United States Congress. "Hiram Rhodes Revels (id: R000166)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- "Hiram Rhodes Revels". Find a Grave. Retrieved 2008-11-05.

| United States Senate | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Albert G. Brown |

U.S. Senator (Class 2) from Mississippi February 23, 1870 – March 3, 1871 Served alongside: Adelbert Ames |

Succeeded by James L. Alcorn |