History of hotel fires in the United States

Hotel fires in the United States have had significant repercussions. For example, on January 10, 1883, in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, a hotel fire killed 80 people. A few weeks earlier Lucius W. Nieman had become editor of The Daily Journal, now the Milwaukee Journal. The newspaper told the "appalling story of neglect, falsehood, manipulation, and concealing of truth that had preceded the tragedy".[1] According to Nieman, it was the reporting of that story that gave his paper a fair share of the Milwaukee newspaper readers, who also had two political and three German newspapers.

The National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) has documented several dozen hotel fires in the United States since the 1930s that have killed more than ten people each, deeming these incidents to be fires of historical note.[2] The Winecoff Hotel fire of December 7, 1946, in Atlanta, Georgia, which claimed 119 lives, is the deadliest hotel fire disaster in the history of the United States.[3] The last fire in the United States which killed ten or more people according to the NFPA took place at the Dupont Plaza in San Juan, Puerto Rico in December 1986, which claimed 98 lives and caused 140 injuries.

1890s

Newhall House Hotel

On January 10, 1893, a fire destroyed the Newhall House Hotel in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, killing anywhere from 64 to 80 persons.[4]

Windsor Hotel

On March 17, 1899, in what was the deadliest hotel fire in New York City's history, the Windsor Hotel (Manhattan) was destroyed, with approximately 86 being killed.[5]

1900s

Park Avenue Hotel

On February 22, 1902, the Park Avenue Hotel in New York City, New York was partially destroyed by a million dollar fire that killed 14.[6]

1930s

Kerns Hotel

On December 11, 1934, shortly before 5:30 am, a fire broke out in the Kerns Hotel in Lansing, Michigan, killing 32 people and injuring 44 people, including 14 firemen. Two of the injured people later died, bringing the death toll to 34. The 211-room four-story hotel had been constructed of brick with a wooden interior, and the fire spread rapidly through the interior, trapping many of the hotel's 215 guests inside their rooms and forcing them to escape via fire ladders or life nets.[7][8] Among the dead were seven Michigan state legislators: state senator John Leidlein and state representatives T. Henry Howlett, Charles D. Parker, Vern Voorhees, John W. Goodwine, Don E. Sias, and D. Knox Hanna, who were in town for a special session of the state legislature. Several other state legislators were injured, but survived.[9][10][11] The fire was thought to have been caused by careless smoking.[8] It is regarded by the Lansing Fire Department as the worst fire disaster in Lansing's history.[7]

Terminal Hotel

On May 16, 1938,[12] a fire broke out in the Terminal Hotel in Atlanta, Georgia, killing 35 people, although some sources claim the death toll was either 27 or 34.[2] The five-story hotel, located at Spring and Mitchell Streets across the street from Terminal Station in the Hotel Row District,[13] was fully ablaze just minutes after the alarm bell sounded shortly after 3 am[14] The fire broke out in the basement and shortly afterwards the kitchen boy fled from the hotel screaming "O Lawdy, fire".[14] Soon after the fire team arrived the roof collapsed, hampering rescue efforts. Because the rapid deterioration of the hotel, traffic was blocked off for blocks around as the walls like the roof were in danger of collapsing.[14] One hotel guest reported having to jump from the second floor elevator cage. The fire spread quickly, choking off fire escapes and stairs just a few seconds after it caught.[14] Several people were killed leaping from the building, including William Oscar Webster, a railroad engineer from Columbus, Georgia who had jumped from a fourth floor window.[14] Firemen reported that they later found a whole family dead in one room, a woman in a rocking chair, a man and a small boy stretched across the bed, with a little girl kneeling by it.[14]

George P. Jones, the hotel manager at the time reported that there were about 75 people in the hotel at the time of the fire; a substantial number of them were railroad workers.[14] Fire Chief O.J. Parker described the disaster as "the deadliest in the history of Atlanta".[15] After the fire the hotel was rebuilt in 1938 and not included in the Hotel Row District.[16]

Eight years later, in 1946, a fire in the Winecoff Hotel in Atlanta became the deadliest hotel fire in American history, killing 119 people.

1940s

Marlborough Hotel

On January 3, 1940, a fire broke out in the Marlborough Hotel in Minneapolis, Minnesota, killing 19 people.[2] It was the city's deadliest fire.[17] The fire burned quickly through the aging walls and doors and engulfed most of the hotel's 56 single rooms and 23 apartment units where some 123 tenants were sleeping.[18] The guests either fled through the corridors with coats over their heads or jumped from their rooms and were killed because the stairways were blocked by the fire.[17][18] Some fell to their deaths when floors collapsed, notably the second floor, and buried them in the basement under tons of debris.[18] One child was trapped on the third floor of the hotel and screamed for 15 minutes before he died in the flames.[17] One man, James Brown, pushed his wife Mabel out of the window when she refused to jump; she was killed but he survived. Another jumped head-first out of the window and was killed instantly.[17] A resident across the street reported that he awoke to hear "the worst screams I ever heard" and saw that half the block in which the hotel was located was completely ablaze.[17]

Fifteen fire engines and five trucks containing some 130 firemen were called to the fire in icy January conditions, temperature −5 °C.[17] At least 40 people were injured in the fire including 2 firemen and 23 required hospital treatment.[17] 18 were reportedly taken to the General Hospital and the others to Abbott and Swedish hospitals.[17] The hotel was completely gutted and reduced just to a "charred hollow rectangle". Fire chief Huttner initially though the fire was caused by a boiler that had exploded in the furnace room,[17] but it was later concluded that it was a "heat explosion" caused by a burning cigarette thrown into the garbage chute which had set fire to the thin wooden walls of the hotel. The garbage caught fire and became a ball of fire that exploded in "volcanic violence".[19]

Gulf Hotel

On September 7, 1943, a fire broke out in the Gulf Hotel in downtown Houston, Texas, killing 55 people.[2] The fire remains the cause of the worst loss of life in a fire in Houston's history.

New Amsterdam Hotel

On March 28, 1944, a fire, believed to have been deliberately set, destroyed the New Amsterdam Hotel in San Francisco, California. The fire, the worst in that city since the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, claimed 22 lives, and injured 27 others.[20]

General Clark Hotel

On January 16, 1945 a fire at the General Clark Hotel in Chicago, Illinois claimed 14 lives.[21]

La Salle Hotel

On June 5, 1946, a fire broke out in the La Salle Hotel in Chicago, Illinois, killing 61 people, many of them children.[2][22] The fire began in the Silver Grill Cocktail Lounge on the lower floor on the La Salle Street side adjacent to the lobby before ascending stairwells and shafts[23] The fire started either in the walls or in the ceiling according to the Chicago Fire Department around 12:15 am but they didn't receive their first notification of the fire until 12:35 am[24] The fire quickly spread through the highly varnished wood paneling in the lounge and the mezzanine balcony overlooking the lobby. While a significant number died from flames, a greater number of deaths were caused by suffocation from the thick, black smoke.[25] Around 900 guests were able to leave the building but some 150 had to be rescued by the fire services and by heroic members of the public, including two sailors who were reported to have rescued 27 people between them.[24][25] Two-thirds of hotel fire deaths in 1946 occurred in the La Salle and Winecoff (Atlanta) fires.[26] The hotel fire was devastating enough to prompt the Chicago city council to enact new hotel building codes and fire-fighting procedures, including the installation of automatic alarm systems and instructions of fire safety inside the hotel rooms.[25] The hotel was refurbished after the fire and was finally demolished in July 1976; its lot is now occupied by the Two North LaSalle office building.

Canfield Hotel

On June 19, 1946, just two weeks after the La Salle Hotel fire, a fire broke out in the six-story 200-room Canfield Hotel in Dubuque, Iowa, killing 19 people.[2] The fire started around 11:30 pm and destroyed the four-story section of the building, which was built in 1891. The fire broke out in a closet near the cocktail lounge on the ground floor. Contributing factors that added to the severity of this incident were delayed alarms, open stairways, and the presence of combustible materials.[27] According to fire captain Harold Cosgrove, 30 people had to be rescued by jumping onto nets and 27 were carried down the ladders.[28]

Winecoff Hotel

On December 7, 1946, a fire broke out in the Winecoff Hotel in Atlanta, Georgia, killing 119 people.[2] As of 2012 it remained the worst hotel fire in United States history and prompted many changes in building codes in the whole country.[29]

The fire started in the 15-story building early in the morning, and engulfed all the floors of the hotel. People were caught unaware and were trapped in the upper floors. Many people jumped out of windows; many of them died this way. The only route for people to escape was a single stairway; the building had neither fire sprinklers nor fire escapes, fire doors, or even an alarm bell. The fire spread throughout the building via the single stairway. Atlanta fire fighters could reach only up to the eighth floor with ladders, and the nets they had spread could not hold many who jumped into them—holding capacity was limited to jumps from up to 70 ft—and many people died on the sidewalks behind the hotel.[29][30]

Guests at the hotel included teenagers attending a Tri-Y Youth Conference organized by the YMCA in the city, Christmas shoppers, and people in town to see Song of the South. Arnold Hardy, a 26-year-old graduate student at Georgia Tech, became the first amateur to win a Pulitzer Prize for Photography for his snapshot of a woman, later identified as survivor Daisy McCumber, in mid-air after jumping from the 11th floor of the hotel during the fire.[31] McCumber, born in 1905, broke her back, pelvis and both legs, but survived. Over a ten-year period, she underwent seven surgeries and lost a leg, but still worked until retirement age and lived until 1992. A plaque was erected at the scene as a memorial to the dead and the survivors, and to the fire-fighters who, with limited resources, tackled the fire and its consequences.[29]

1950s

Barton Hotel

Considered one of Chicago's worst flophouse blazes,[32] a fire broke out in the five-story Barton Hotel on West Madison[33] on February 12, 1955, killing 29 people and gutting the hotel, a 49-year-old structure with 336 tiny 4ftx6ft rooms with 7-ft high chicken-wire ceilings, charging 65 cents per person per night.

There were 245 people staying at the hotel on the night of the fire. At 2 am when the night manager came out of his office room to check a commotion in the hall, a huge fire had broken out which singed him badly. He immediately rushed to his office and rang the fire alarm bell and rushed to wake the people sleeping in the rooms by banging on their doors; many were fast asleep after the previous night's drinking binge. Failing in his attempts, the manager ran out of the hotel. Many people who woke up were unable to escape due to the smoke and flames, and died in the rooms. A few lucky ones broke the window panes and jumped out. Many escaped down the fire escape. The fire department saved many lives with their ladders, ropes and water jets, and attempted to douse the fires. 29 people died in the fire, many of them charred beyond recognition. The fire is attributed to a cigarette butt thrown accidentally by a 70-year-old man into a utensil containing alcohol used for massaging; he too was killed.[32]

1960s

Surfside Hotel

On November 18, 1963, a fire broke out in the Surfside Hotel convalescent home[34] in Atlantic City, New Jersey, killing 25 people, mostly elderly Jews, including three Orthodox rabbis, Morris Fishman, Mosheh Shapiro and his son, Joshua Shapiro. These Rabbis were not killed in the fire; rather, they were listed in a separate news article as providing counseling. Also Morris Fishman was a Conservative rabbi who knew the owners from his previous job at Community Synagogue.[2] [35] The fire spread from the hotel to adjacent buildings, including five hotels and a rooming house, leading to walls and roofs collapsing. More than 200 firemen were sent to the scene. The owners of the hotel and a family of seven were reported to have jumped out of a window about 15 feet from the ground.[35] Two people, Anne Shalit (63) and George Dzwonar (46) were admitted to hospital.[35] The cause of the fire was unknown but police strongly suspected arson, given that a previously convicted arsonist was seen by a bus driver near the Surfside Hotel less than an hour after the fire broke out.[35]

Hotel Roosevelt

On Sunday, December 29, 1963, a fire broke out in the 13-floor Hotel Roosevelt in Jacksonville, Florida, killing 22 people.[2] The fire broke out at around 7:30 am in the ballroom's ceiling due to faulty wiring, and by 7:45 am, the Jacksonville Fire Department had been called, later bringing three fire engines, two ladder trucks, a fire chief and two assistant chiefs and the mayor at the time, W. Haydon Burns, requested 8 helicopters to help from the U.S. Navy but only four people were saved from the roof when helicopters from Naval Air Station Jacksonville, Naval Air Reserve Training Unit Jacksonville, and Naval Air Station Cecil Field came to the rescue.[36] Some 475 were successfully rescued from the hotel fire which by 9:30 am had been suppressed. However, 21 of the people who died in the fire died in their beds of smoke inhalation; the other person was actually assistant chief J.R. Romedy of the Jacksonville Fire Department, who died of a heart attack on the scene during the rescue effort.

The fire was the worst in Jacksonville's history in terms of a single-day death toll; even the Great Fire of 1901 had fewer fatalities. The hotel closed a year later and reopened as Jacksonville Regency House, an apartment block for the elderly, but it closed again in 1989. On February 28, 1991, the site was added to the U.S. National Register of Historic Places, but the building was empty for nearly 14 years until it was converted to luxury apartments named "The Carling".[37] Extensive archives on the fire, including valuable photographs, exist within the Jacksonville Fire Museum.

Hotel Carleton

In January 1966, a fire broke out in the Hotel Carleton in St. Paul, Minnesota, killing 11 people.[2]

Paramount Hotel

On January 28, 1966, a fire broke out in the 11-story Paramount Hotel in Boston, Massachusetts, killing 11 people,[2] and injuring 57. Preceding the fire, an odor of natural gas was detected in the stairway going down to the first floor. The explosion was caused by a gas leak from a main pipe in Boylston Street that seeped into the hotel's basement.[38]

Lane Hotel

In September 1966, a fire broke out in the two-story 33-room wooden Lane Hotel in the main business district of Anchorage, Alaska, killing 14 people.[2] The fire started at 1:17 am and spread rapidly; the flames were reported to be very intense which burned many bodies beyond recognition.[39] Several victims, however, died of asphyxiation due to the heavy wood smoke. More than half of the occupants of the hotel died in the fire; there was only a reported 25 people registered in the hotel at the time.[39] The owner of the hotel, Virgil McVicker, believed that the fire was caused by an explosion in the boiler room.[39]

1970s

Ozark Hotel

On March 20, 1970, a fire caused by arson broke out in the lobby, at about 2:30 am (a clock on the second floor had melted, showing the time as 2.45) spreading through two stairways and all the halls in the Ozark Hotel in Seattle, Washington, killing 20 people (14 men and six women) and seriously injuring 10 others in a time span of 63 minutes, until the fire fighters extinguished the fire. The hotel, a 60-year-old building at the time of the fire, was a wooden building of five floors with 60 rooms.[2][40][41] It was said to be the worst arson fire in Seattle.

The hotel, a five-story wooden structure, was known as susceptible to fire hazards. It was well known as “high risk facility” to the Fire Fighting Department. The hotel had been inspected six times from February 6, 1970, to even one day prior to the fire incident. On the night of the fire, 42 of the 62 rooms were occupied. The hotel was known as a “flophouse’ which provided cheap accommodation to many impoverished and elderly people. When the fire was set at two places (in the main stairwell on the first floor and also at the rear side of the hotel on the second floor) in the hotel by arsonists, at about 2:30 am, a wayside straggler had alerted the authorities.[41] The saving grace in the building was an open core area which had a large shaft up to the 2nd floor, which enabled two people to escape to safety. As the fire was a deliberate act, it quickly engulfed the two staircases and the lobby that separated them. The top two floors completely collapsed in the fire. The open transoms in the room further helped in spreading the fire. Those who could not reach the fire escape tried to jump out of the windows of their rooms. The fire fighting department, who mobilized their forces immediately on hearing about the fire, and had inducted 14 engines and 4 ladders with a complement of over 100 firemen and 20 units, were able to control the fire within 50 minutes of their arrival at the scene of the fire. The causes for death of people due to the fire were deduced as due to smoke inhalation, burns, cuts and injuries. Losses due to the fire were estimated to be US $100,000 at the time.[41]

No arsonists were caught in spite of a large contingent of police force inducted to inquire into the causes of fire.[41]

Noting that the building lacked modern fire fighting facilities, major changes in the city's fire code were initiated thereafter during President Ronald Reagan’s time. However, these rules are reported to have resulted in homelessness for many people in Seattle in the 1980s, since people living in low income housing could not afford to follow the stringent fire codes and laws and hence deserted their houses. Even small hotels with single occupancy rooms could not survive these rules.[41][42][43]

Ponet Square Hotel

On September 13, 1970, a fire broke out in the Ponet Square Hotel at Pico Boulevard and Grand Avenue in Los Angeles, killing 19 people.[2] After the fire, safety doors to enclosed stairwells – later known as "Ponet Doors", after the hotel – were installed in all pre-1943 residential structures of three stories or more in Los Angeles.[44]

Pioneer International

In December 1970, a fire broke out in the 11-story Pioneer International on the corner of North Stone Avenue and Pennington Street in Tucson, Arizona, killing 28 people. Among the dead were, 13 prominent northern Mexican citizens, including two grandchildren of Ignacio Soto, a former governor of Sonora; the wife and five children of Francisco Luken, a Sonora police chief; and Jose Jesus Antillon of Hermosillo, a top Mexican cardiologist.[45] The fire also killed several children and teenagers and injured 27.[2]

The hotel, built in 1929, suffered a fire which started on the sixth floor and spread rapidly through the hallways and staircases, trapping over 60 people.[45] However, although more than 60 people were trapped, more than half escaped through hotel windows.[46] The majority of the occupants of the hotel at the time were attending three different banquets on the ground floor and those 650 or so people were easily evacuated.[45] Of the 28 who died, 16 died of carbon monoxide poisoning, 7 from burns and 1 from smoke inhalation.[46] One woman died after jumping from the seventh floor and three others died from jumping, one of them a small boy, who was found on the lower east wing roof.[46] Two firemen were injured including a fire captain who hung upside down on a 45-foot broken ladder for 25 minutes before being rescued.[45]

Although the hotel was supposed to be fireproof, synthetic carpeting, vinyl wall covering, painted doors and frames and open stairways fuelled the spread of the fire, especially given that there were no sprinklers or smoke detectors installed at the time.[46] The fire was reported to be an arson attack and a 16-year-old, Louis C. Taylor was taken into custody over the incident which caused $2.5 million in damage, charged with felony homicide and arson.[45] He was found to be guilty of starting a fire in at least two places in the hotel and was imprisoned for life, although he did not then and has not since admitted causing the fire.[46] He was released from custody in April 2013 after his conviction was called into question.[47]

The hotel remained standing after the fire and was renovated in 1977 and converted into offices. Since the conversion, paranormal activity has frequently been reported in the building, from the smell of smoke during the night, running on the upper floors, lights turning on and off with no apparent reason and office employees reportedly seeing apparitions.[46]

Pennsylvania House Hotel

On January 16, 1972, a fire broke out in the Pennsylvania House Hotel in Tyrone, Pennsylvania, killing 12 people.[2] The 75-year-old hotel lacked alarm systems, sprinklers, smoke detectors, and stairway fire doors. None were required when the hotel was built, and there were no local safety codes that required subsequent installation.[48] The fire took place in icy conditions in which rescue efforts took place using ice axes. 31 people were treated at Tyrone Hospital, including 28 people who served as volunteer firemen, mainly treated for frostbite and smoke inhalation rather than burns.[49]

Washington House Hotel

On August 25, 1974, a fire broke out in Washington House Hotel at the corner of Fairfax and Washington streets in Berkeley Springs, West Virginia, killing 12 people.[2] The fire, which broke out about 2:30 am, killed the occupants in their beds and spread from the brick building to seven adjoining buildings.[50] The fire's intense heat melted the face of the clock in the Morgan County Courthouse's tower.[51]

Pomona Hotel

In July 1975, a fire broke out in the Pomona Hotel in Portland, Oregon, killing 11 people (initially reported as eight).[2] The fire also injured 26 people, 8 of them critically.[52] The alarm was raised about 11 pm when a man saw smoke drifting out of a second story window and a man was hanging from a second floor window, later rescued by firemen. The extent of the fire was minimal but it created a considerable amount of thick black smoke which hampered rescue efforts.[52] The fire was an arson attack and a man named Newvine was taken into custody, having been seen at the hotel and purchasing gasoline from a station.[52]

Hotel Pathfinder

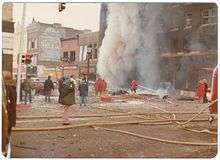

On January 10, 1976, a fire broke out in the Hotel Pathfinder in Fremont, Nebraska, killing 20 people.[2] The fire was fueled by a natural gas leak at the hotel.[53] The gas leak caused a major blast which blew out the windows of the hotel, with the sheer force of the blast shattering glass out as far as nine blocks away. A flight instructor flying over the city at the time experienced severe turbulence.[54]

Stratford Hotel

In January 1977, a fire broke out in the Stratford Hotel in Breckenridge, Minnesota, killing 17 people.[2]

Wenonah Park Hotel

In December 1977, a fire broke out in the Wenonah Hotel in Bay City, Michigan, killing 10 people.[2][55]

Coates House Hotel

On January 28, 1978, a fire broke out in the six-story Coates House Hotel at 1005 Broadway in Downtown Kansas City, Missouri, killing 20 people and injuring at least six.[2] It is the worst fire disaster in the history of Kansas City.[56]

The hotel was originally built in 1867 and over the years Presidents William McKinley, Grover Cleveland and Theodore Roosevelt stayed there.[57] The hotel was listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

The fire broke out around 4 am and the Kansas City, Missouri Fire department was alerted at 4:12 am by the Coates House desk clerk.[57] The initial response by the fire department was three pumpers (engine companies), two trucks (ladder companies) and a battalion chief. The station of the first companies due at the scene was only 100 feet down an alley to the southeast of the Coates House, yet they saw no smoke or fire when they arrived about two minutes later. Other companies arriving from the south on Broadway saw smoke emitting from a few upper story windows of the hotel.

At 4:17 a.m. Battalion Chief 102 requests a second alarm, and 3 more pumpers and one truck company are assigned.

By that time, occupants of the building began leaning and climbing out of upper floor windows. Ladder company Truck 6 tries to extend the aerial ladder of their 25-year-old-plus truck when it froze barely a dozen feet in the air. Some of the hotel's occupants began to jump from the choking smoke and intense heat. At least five of the fire's fatalities were jumpers as the meager first-response fire department manpower was overwhelmed by both rescues and firefighting.

At 4:22 a.m. a third alarm is sounded, three more pumpers and another truck company respond. Over about the next 10 minutes, one each additional pumper and truck companies are dispatched to the fire. At 4:33 a.m. a fourth alarm is sounded and three more pumper companies respond.

Four additional companies, including the Kansas City, KS Fire department, are piece-mealed into the fire over the next 30 minutes.

At the height of the fire, 23 fire trucks and at least 90 firemen were on the scene – [57] more than three-quarters of all available on-duty Kansas City fire companies – and the fire took more than four hours to bring under control.

The Coates House Hotel before this January night was an about one-third city block long and about one-quarter block deep, U-shaped building. That part of the south leg of the U was on fire.

The fire reduced that portion of the Coates House Hotel to nothing more than a charred frame and later had to be demolished by wrecking crews (the front and north part of the U are occupied by offices today).

Over 100 of the survivors were taken by bus to the Salvation Army Center in the southeast of the downtown Kansas City area; the Salvation Army raised $4000 to help the victims of the disaster.[57]

Allen Motor Inn

On November 5, 1978, a fire broke out in the Allen Motor Inn in Honesdale, Pennsylvania, killing 12 people and injuring five. Frederick Weiler Blady, a 36-year-old drifter from New Jersey, was arrested and charged with arson in connection with this fire, and with a previous fire at the same hotel on October 5, 1978. Blady was convicted for the October fire, but was found not guilty of the fatal November conflagration.[2]

Holiday Inn (Greece, New York)

The 1978 Holiday Inn fire broke out at the Holiday Inn-Northwest which was located at 1525 West Ridge Road in the Town of Greece, near Rochester, New York on November 26, 1978, and killed 10 people.[58] Seven of the fatalities were Canadian;[59] more than 130 Canadians were staying in the hotel at the time on a holiday shopping trip.

The fire started on the first floor between the north and west wings of the hotel around 2:30 am. Cleaning supplies and paper products were stored in a closet near the fire's point of origin. Due to fire doors being left opened and the nearby combustible materials the fire spread very rapidly. The fire alarm system was not tied to the local fire department and although some people reported a bell ringing, they failed to realize it was the emergency alarm bell.[60] The fire was not reported to the fire department until 2:38 am when an off-duty firefighter passing by reported it. Initially the police did not consider the fire suspicious. An expert fire investigator was brought in from New York City to assist with the investigation. He discovered that an uncommon highly flammable chemical was used to start the fire in the form of a liquid which was ignited inside a store cupboard under the first floor stairwell.[61] The fire was officially ruled as an arson attack. No one was ever charged with this crime, and the case remains open today.

Holiday Inn (Cambridge, Ohio)

On July 31, 1979, a fire broke out in the Holiday Inn in Cambridge, Ohio, killing 10 people and injuring 82.[2] It was the handiwork of an arsonist, Gerald Willey of Randolph, Ohio, who had poured gasoline on the carpet on the first floor of the two-story road side motel and set it on fire with a lighted match. Willey was later arrested and convicted of one count of aggravated arson and 10 counts of involuntary manslaughter, and was sentenced to 14-to-50 years at Mansfield Reformatory. Despite the fact that the cause of the fire was arson, a well-known Cincinnati lawyer named Stanley Chesley had argued that the people had died on the second floor of the motel due to choking by toxic smoke and not by fire and that the building was not designed properly. It was argued that the floor-to-ceiling windows on the back side of each room were picture windows (not designed/able to be opened) resulting in trapping people in their rooms resulting in their deaths. However, the case was settled out of court for US$6 million.[62]

1980s

MGM Grand Hotel

On November 21, 1980, a fire broke out in the MGM Grand Hotel (now Bally's Las Vegas) in Paradise, Nevada, killing 85 people.[2] most through smoke inhalation.[63] The tragedy remains the worst disaster in Nevada history, and the third-worst hotel fire in modern U.S. history.

At the time of the fire, approximately 5,000 people were in the hotel and casino, a 26-story luxury resort with more than 2,000 hotel rooms. Just after 7:00 on the morning of November 21, 1980, a fire broke out in a restaurant known as The Deli. The Clark County Fire Department was the first agency to respond. Other agencies that responded included the North Las Vegas Fire Department, Las Vegas Fire & Rescue and the Henderson Fire Department. Smoke and fire spread through the building, killing 85 people and injuring 650, including guests, employees and 14 firefighters. While the fire primarily damaged the second floor casino and adjacent restaurants, most of the deaths were on the upper floors of the hotel, and were caused by smoke inhalation. Openings in vertical shafts (elevators and stairwells) and seismic joints allowed toxic smoke to spread to the top floor. The disaster led to the general publicizing of the fact that during a building fire, smoke inhalation is a more serious threat than flames. 75 people died from smoke inhalation and carbon monoxide poisoning and 4 from smoke inhalation alone; only 4 people died as a result of burns.[63]

After the fire, the hotel was repaired and improved, including the addition of fire sprinklers and an automatic fire alarm system throughout the property, and sold to Bally's Entertainment, which changed the name to Bally's Las Vegas. The tower in which 85 people died is still operating as part of the hotel today. A second tower, unaffected by the fire, opened in 1981. On February 10, 1981, just 90 days after the MGM fire, another lesser-scale fire broke out at the Las Vegas Hilton. Because of the two incidents, there was a major reformation of fire safety guidelines and codes.

Stouffer's Inn of Westchester

In December 1980, a fire broke out at the Stouffer's Inn of Westchester, a newly built hotel and conference center in Purchase, New York, killing 26 people.[2] The fire broke out in the two-level conference center of the hotel, adjacent to the four-story, 365-room hotel tower.[64] It spread rapidly due to a lack of sufficient sprinklers and the use of highly flammable carpeting and wall coverings; New York had no statewide fire code at the time.[65] The fire was said to be a deliberate act but no one was convicted of causing it. The coffee waiter who was the chief suspect was arrested and initially convicted by the jury, but was later released by the judge for lack of evidence. The hotel reopened on April 4, 1981, four months after the fire disaster.[66][67] It today operates as the Renaissance Westchester Hotel.

Westchase Hilton Hotel

In March 1982, a fire broke out in the Westchase Hilton Hotel in Houston, Texas.[2] 12 people died in the hotel, which was opened in 1980, due to the inadequacy of the escape routes. A report brought out by the National Fire Protection Association has identified the reason for the cause of deaths as the location of the stairways at the end of the corridor. As the smoke filled the hallway, people found it hard to reach the staircase for escape to safety and died out of suffocation. Another reason mentioned is that the staff of the building had reset the alarm system preventing transmission of information of the fire to the Fire Department.[68][69] The fire was limited to one room of the hotel, on the fourth floor.[70]

Alexander Hamilton Hotel

An arson fire swept through the Alexander Hamilton Hotel in Paterson, New Jersey on October 18, 1984, killing 15, and injuring 60 others. A resident of the hotel, Russell William Conklin, was convicted of arson and manslaughter, and served 12 years in prison before being released in 1997.[71]

Dupont Plaza

Fire broke out in the Dupont Plaza Hotel in San Juan, Puerto Rico on New Year's Eve (December 31), 1986, killing 98 people[2] and injuring 140. It was described as one of the worst such fires of the century. The National Fire Protection Association conducted the inquiry into the causes of the fire, in association with the U.S. Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms and Puerto Rican authorities. It was established that the fire originated in a deliberate act of arson; three people were convicted for this. The inquiry report found that fire spread from new furniture temporarily stacked in a ballroom of size 5.5×9.4×1.8 m; the furniture consisted of dressers made of wood and particle board, mattresses and sofa beds, packed in cartons. The fire originated in this room and quickly engulfed the casino and lobby. The lobby was filled with smoke throughout the first and second floors of the hotel and spread to other floors too. The flames spread over an area of 437 m². Most bodies were charred beyond recognition; 84 charred bodies were found in the casino, five in the lobby area, three in an elevator and one in a guest room on the west side of the hotel.

National TV networks gave live coverage of the fire and the rescue operations undertaken by Puerto Rican firefighters, using helicopter services and rescuing people from the roof of the hotel.[72]

2000s

Mizpah Hotel

On October 31, 2006, a fire roared through the 84-year-old Mizpah Hotel in Reno, Nevada, which claimed 12 lives. Casino cook Valerie Moore was convicted of setting the fire, and she was sentenced to 12 consecutive life prison terms without parole.[73]

References

- ↑ Scott Cutlip (Fall !964) "Portrait without blemishes", Columbia Journalism Review, pp 42,3

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 "Summary of Fire Incidents 1934–2006 in Hotel Fires in the United States as Reported to the NFPA, with Ten or more Fatalities" (PDF). National Fire Protection Association. January 2008. Retrieved December 3, 2010.

- ↑ "Historic Fires". University of Texas at Austin. Retrieved December 4, 2010.

- ↑ https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1368&dat=19810110&id=4oBQAAAAIBAJ&sjid=DRIEAAAAIBAJ&pg=4330,1951100&hl=en

- ↑ "Article Window". Retrieved September 6, 2016.

- ↑ "GOTHAM HOTEL BURNS; AT LEAST 14 ARE KILLED (February 22, 1902)". Retrieved September 6, 2016.

- 1 2 "Box 23". Lansing Fire Department. Archived from the original on 2013-07-27. Retrieved 2016-01-08.

- 1 2 "The Hotel Kerns Fire". cadl.org. Capital Area District Library. Archived from the original on 2013-04-03. Retrieved 2016-01-08.

- ↑ "National Affairs: Legislators at Lansing". Time. Time.com. 1934-12-24. Retrieved 2016-01-08. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Beitler, Stu, ed. (2007-11-02). "Lansing, MI Hotel Kerns Fire Disaster, Dec 1934 (page 1)". Gendisasters.com. Retrieved 2016-01-08.

- ↑ Beitler, Stu, ed. (2007-11-02). "Lansing, MI Hotel Kerns Fire Disaster, Dec 1934 (page 2)". Gendisasters.com. Archived from the original on 2015-01-10. Retrieved 2016-01-08.

- ↑ Atlanta, Ga Fire. Turner Publishing Company. 2000. p. 68. ISBN 1-56311-680-4.

- ↑ Atlanta: Unforgettable Vintage Images of an All-American City. Arcadia Publishing. 2000. p. 34.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Atlanta, Georgia Terminal Hotel Fire, May 1938. Gendisasters. ISBN 0-7385-0751-2. Retrieved December 4, 2010.

- ↑ "1938: Fire destroys Terminal Hotel". Daily Perspective Newspaper Archive. Retrieved December 4, 2010.

- ↑ "Hotel Row District". Government of Atlantic, Georgia. Retrieved December 4, 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Minneapolis has a disastrous fire-20 dead". Gendisasters. Retrieved December 4, 2010.

- 1 2 3 "Life, Vol. 8, No.3". Time Inc. January 15, 1940: 22. ISSN 0024-3019.

- ↑ LIFE 15 Jan 1940, Vol. 8, No. 3. Time Inc. 1940. pp. 22–23. ISSN 0024-3019. Retrieved December 3, 2010.

- ↑ "Article Window". Retrieved September 6, 2016.

- ↑ "Article Window". Retrieved September 6, 2016.

- ↑ Coppola, Damon P. (2007). Introduction to international disaster management. Butterworth-Heinemann. p. 95. ISBN 0-7506-7982-4.

- ↑ Randall, Frank Alfred; Randall, John D. (1999). History of the development of building construction in Chicago (2 ed.). University of Illinois Press. p. 272. ISBN 0-252-02416-8.

- 1 2 "Incident summary". Illinois Fire Service Institute. Retrieved December 4, 2010.

- 1 2 3 "Hotel Lasalle". Chicago Urban History. Retrieved December 4, 2010.

- ↑ "Hotel Fires: Experts work to prevent repetition of conflagrations of last year, the worst in recent U.S. history". Life. Time Inc. 22 (2): 34. January 13, 1947. ISSN 0024-3019.

- ↑ Cote, Arthur E (2004). Fundamentals of Fire Protection. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 30. ISBN 0-87765-595-2.

- ↑ "Dubuque, IA Devastating Fire at Hotel Canfield, June 1946". Gendisasters. Retrieved December 4, 2010.

- 1 2 3 File:Winecoff-Hotel-Atlanta-03.jpg: Official plaque near the Winecoff Hotel

- ↑ "Historic Fires". Winecoff Hotel Fire. Fire Prevention Services. December 7, 1946. Retrieved December 5, 2010.

- ↑ ""Pulitzer Photo" by Sam Heys". h. Retrieved December 4, 2010.

- 1 2 Cowan, David (2001). Great Chicago fires: historic blazes that shaped a city By. Lake Claremont Press. pp. 77–79. ISBN 1-893121-07-0.

- ↑ D'Eramo, Marco; Thomson, Graeme (2003). The pig and the skyscraper: Chicago, a history of our future By. Verso. p. 239. ISBN 1-85984-498-7.

- ↑ Hellmann, Paul T. (2005). Historical gazetteer of the United States. Taylor & Francis. p. 715. ISBN 0-415-93948-8.

- 1 2 3 4 "Atlantic City, NJ Surfside Hotel Fire, Nov 1963". Gendisasters. Retrieved December 5, 2010.

- ↑ Williamson, Ronald M. (2000). Naval Air Station Jacksonville, Florida, 1940–2000: An Illustrated History. Turner Publishing Company. p. 98. ISBN 1-56311-730-4.

- ↑ Witkowski, Rachel: "Costly renovation of historic buildings pays off for city" Jacksonville Business Journal, April 7, 2006

- ↑ Noonan, William. "Fire Department Journal – The Paramount Hotel Fire". City of Boston. Retrieved December 4, 2010.

- 1 2 3 "Anchorage, AK Lane Hotel Fire, Sep 1966". Gendisasters. Retrieved December 5, 2010.

- ↑ Schneider, Richard (2007). Seattle Fire Department. Arcadia Publishing. p. 81. ISBN 0-7385-4867-7.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Shane Sasnow. "Ozark Hotel Fire Report" (PDF). Shensdommain.net. Retrieved December 6, 2010.

- ↑ "Fire – Major Incidents". City Government of Seattle. Retrieved December 4, 2010.

- ↑ "Arsonist kills 20 and injures 10 at the Ozark Hotel fire in Seattle on March 20, 1970.". Histoooorylink.org. Retrieved December 6, 2010.

- ↑ Harrison, Scott (November 15, 2010). "Stratford Apartments fire". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved December 4, 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Tucson, AZ Pioneer International Hotel Fire, Dec 1970". Gendisasters. Retrieved December 5, 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Haunted by a tragedy in Tucson Tuesday". Tucson Citizen. October 27, 2009. Retrieved December 4, 2010.

- ↑ "Man convicted in deadly Ariz. fire walks free". guardian.co.uk. Retrieved April 30, 2015.

- ↑ Governor's Commission on Fire Prevention and Control (March 1976). "A report to Milton J. Shapp, Governor of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania" (PDF). lcfa.com. p. 5. Retrieved December 4, 2010.

- ↑ "Tyrone, PA Pennsylvania House Hotel Fire, Jan 1972". Gendisasters. Retrieved December 5, 2010.

- ↑ Professional Safety, Volume 21. American Society of Safety Engineers. 1976.

- ↑ Bosely, Candice (August 13, 2006). "Berkely Springs has fiery history by". The Herald-Mail. Retrieved December 4, 2010.

- 1 2 3 "Portland, OR, Hotel Fire Caused by Arsonist, July, 1975". Gendisasters. Retrieved December 5, 2010.

- ↑ Bowen, Don (January 10, 2009). "The Explosion that changed Fremont". Fremont Tribune. Retrieved December 4, 2010.

- ↑ "Fremont, NE, Hotel explosion caused gas, Jan 1976". Gendisasters. Retrieved December 5, 2010.

- ↑ D. Smith, Harold (1981). Michigan municipal review, Volumes 54–56. Michigan Municipal League.

- ↑ "The Worst Fire in Kansas City History". Kansas City Library. Retrieved December 5, 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 "Kansas City, MO, Coates House Hotel Fire, Jan 1978". Gendisasters. Retrieved December 5, 2010.

- ↑ Fire command, Volume 46. National Fire Protection Association. 1979.

- ↑ "Push on to solve NY arson case that killed 7 Canadians". The Star. November 24, 2010. Retrieved December 3, 2010.

- ↑ Burgess, John H. (1981). Human factors in built environments. Environmental Design & Research Ctr. p. 78. ISBN 0-915250-38-1.

- ↑ McDermott, Meaghan (November 27, 2010). "Fatal 1978 Holiday Inn fire still frustrates Greece officials". Democrat and Chronicle. Retrieved December 3, 2010.

- ↑ Cincinnati Magazine, Vol. 18, No. 6. Cincinnati Magazine. March 1985. Retrieved December 4, 2010.

- 1 2 "fire.co.clark.nv.us". Retrieved 2009-08-02.

- ↑ "Schenectady Gazette – Google News Archive Search". google.com. Retrieved April 30, 2015.

- ↑ "Lessons of the Stouffer's Inn fire, 25 years later". The Journal News - lohud.com. Retrieved April 30, 2015.

- ↑ "Stouffer's Inn, Where 26 Died in Arsonist's Fire, Will Reopen". New York Times. March 19, 1981. Retrieved December 3, 2010.

- ↑ Stouffer's Fie Defense stiffening. New York Magazine. February 14, 1983. Retrieved December 4, 2010.

- ↑ Cote, Arthur E. (2003). Organizing for Fire And Rescue Services. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 276. ISBN 0-87765-577-4. Retrieved December 4, 2010.

- ↑ Nowak, Andrzej S.; Galambos, Theodore V. (1990). Making buildings safer for people: during hurricanes, earthquakes, and fires. Springer. p. 93. ISBN 0-442-26473-9. Retrieved December 4, 2010.

- ↑ Brannigan, p. 451

- ↑ "The Evening Independent – Google News Archive Search". Retrieved September 6, 2016.

- ↑ Craighead, Geoff (2009). High-Rise Security and Fire Life Safety. Butterworth-Heinemann. pp. 132–133. ISBN 1-85617-555-3. Retrieved December 4, 2010.

- ↑ https://www.usfa.fema.gov/downloads/pdf/publications/tr_164.pdf