Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago

| |

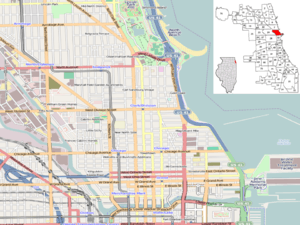

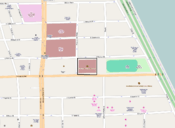

Location in Chicago's Near North Side community area | |

| Established |

1967 (current location since 1996) |

|---|---|

| Location |

220 East Chicago Avenue, Chicago, Illinois 60611-2643 United States |

| Coordinates | 41°53′50″N 87°37′16″W / 41.8972°N 87.6212°W |

| Director | Madeleine Grynsztejn |

| Website | mcachicago.org |

The Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA) Chicago is a contemporary art museum near Water Tower Place in downtown Chicago in Cook County, Illinois, United States. The museum, which was established in 1967, is one of the world's largest contemporary art venues. The museum's collection is composed of thousands of objects of Post-World War II visual art. The museum is run gallery-style, with individually curated exhibitions throughout the year. Each exhibition may be composed of temporary loans, pieces from their permanent collection, or a combination of the two.[1]

The museum has hosted several notable debut exhibitions including Frida Kahlo's first U.S. exhibition and Jeff Koons' first solo museum exhibition. Koons later presented an exhibit at the Museum that broke the museum's attendance record. To date, the most attended exhibition has been the 2015 David Bowie Is exhibit, shattering previous records with over 193,000 attendees.[2] Its collection, which includes Jasper Johns, Andy Warhol, Cindy Sherman, Kara Walker, and Alexander Calder, contains historical samples of 1940s–1970s late surrealism, pop art, minimalism, and conceptual art; notable holdings 1980s postmodernism; as well as contemporary painting, sculpture, photography, video, installation, and related media. The museum also presents dance, theater, music, and multidisciplinary arts.

The current location at 220 East Chicago Avenue is in the Streeterville neighborhood of the Near North Side community area.[3] Josef Paul Kleihues designed the current building after the museum conducted a 12-month search, reviewing more than 200 nominations.[4] The museum opened at its new location June 21–22, 1996, with a 24-hour event that drew more than 25,000 visitors.[5] The museum was originally located at 237 East Ontario Street, which was originally designed as a bakery. The current building is known for its signature staircase leading to an elevated ground floor, which has an atrium, the full glass-walled east and west façades giving a direct view of the city and Lake Michigan.

History

The Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA) Chicago was created as the result of a 1964 meeting of 30 critics, collectors and dealers at the home of critic Doris Lane Butler to bring the long-discussed idea of a museum of contemporary art to complement the city's Art Institute of Chicago, according to a grand opening story in Time.[6] It opened in fall 1967 in a small space at 237 East Ontario Street that had for a time served as the corporate offices of Playboy Enterprises.[7] Its first director was Jan van der Marck.[8] In 1970 he invited Wolf Vostell to make the Concrete Traffic sculpture in Chicago.[9]

Initially, the museum was conceived primarily as a space for temporary exhibitions, in the German kunsthalle model. However, in 1974, the museum began acquiring a permanent collection of contemporary art objects created after 1945.[10] The MCA expanded into adjacent buildings to increase gallery space; and in 1977, following a fundraising drive for its 10th anniversary, a three-story neighboring townhouse was purchased, renovated, and connected to the museum.[7] In 1978, Gordon Matta-Clark executed his final major project in the townhouse. In his work Circus Or The Caribbean Orange (1978), Matta-Clark made circle cuts in the walls and floors of the townhouse next-door to the first museum.[5][11]

In 1991, the museum's Board of Trustees contributed $37 million ($64.4 million today) of the expected $55 million ($95.7 million) construction costs for Chicago's first new museum building in 65 years.[12] Six of the board members were central to the fundraising as major donors: Jerome Stone (chairman emeritus of Stone Container Corporation), Beatrice C. Mayer (daughter of Sara Lee Corporation founder Nathan Cummings) and family, Mrs. Edwin Lindy Bergman, the Neison Harris (president of Pittway Corporation) and Irving Harris families, and Thomas and Frances Dittmer (commodities).[13][14] The Board of Trustees then weighed architectural proposals from six finalists: Emilio Ambasz of New York; Tadao Ando of Osaka, Japan; Josef Paul Kleihues of Berlin; Fumihiko Maki of Tokyo; Morphosis of Santa Monica, Calif.; and Christian de Portzamparc of Paris.[13] According to Chicago Tribune Pulitzer Prize-winning architecture critic Blair Kamin, the list of contenders was controversial because no Chicago-based architects were included as finalists despite the fact that prominent Chicago architects such as Helmut Jahn and Stanley Tigerman were among the 23 semi-finalists. In fact, none of the finalists had made any prior structures in Chicago. The selection process, which started with 209 contenders, was based on professional qualifications, recent projects, and the ability to work closely with the staff of the aspiring museum.[15]

In 1996, the MCA opened its current museum at 220 East Chicago Avenue, which was the site of a former National Guard Armory between Lake Michigan and Michigan Avenue from 1907 until it was demolished in 1993 to make way for the MCA.[16] The four-story 220,000-square-foot (20,000 m2) building designed by Josef Paul Kleihues,[17] which was five times larger than its predecessor,[18] made the Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA) Chicago the largest institution devoted to contemporary art in the world.[19] The physical structure is said to reference the modernism of Mies van der Rohe as well as the tradition of Chicago architecture.[10]

Operation

The museum operates as a tax-exempt non-profit organization, and its exhibitions, programming, and operations are member-supported and privately funded.[20] It has a board of trustees consisting of four officers, 18 life trustees, and more than 40 trustees.[21] The current board chair is King Harris.[22] The museum also has a director, who oversees the MCA's staff of about 100. Madeleine Grynsztejn replaced 10-year director Robert Fitzpatrick during the 2008 fiscal year in this capacity, and she is the MCA's first female director.[23]

The museum operates with three programming departments: curatorial, performance, and education. Peter Taub is the director of performance programs, Heidi Reitmaier is the Beatrice C. Mayer Director of Education,[24] and Teresa Samala de Guzman is the Chief Operating Officer.[25] The curatorial staff consists of Chief Curator Michael Darling, Curator Naomi Beckwith, Curator Lynne Warren, and Associate Curator Julie Rodrigues Widholm. In 2009, the museum reported $17.5 million in both operating income, 50% of which came from contributions, and operating expenses.[26] Contributions were received from individuals, corporations, foundations, government entities, and fundraising.[27]

The museum is closed Mondays. While the museum has no mandatory admission charge and operates with a suggested admission ($12 general, $7 students and seniors, free for MCA members, members of the military, and children 12 and under), it currently provides free admission every Tuesday, when it has extended hours of operation from 10 a.m. to 8 p.m.[28] During the summers, the museum provides free outdoor Tuesday Jazz concerts.[29] On the first Friday of most months, the museum hosts First Fridays, which is an event featuring local DJs, artists, and other activities.[30] In addition to art exhibits, the museum offers dance, theater, music, and multidisciplinary arts. The programming includes primary projects and festivals of a broad spectrum of artists presented in performance, discussion, and workshop formats.[31]

Exhibitions

Past

In its first year of operation, the museum hosted the exhibitions, Pictures To Be Read/Poetry To Be Seen, Claes Oldenburg: Projects for Monuments, and Dan Flavin: Pink and Gold, which was the artist's first solo show.[5] In 1969, the museum served as the site of Christo's first building wrap in the United States. It was wrapped in more than 8,000 square feet (700 m²) of tarpaulin and rope.[32] The following year it hosted one-person shows for Roy Lichtenstein, Robert Rauschenberg, and Andy Warhol.

The MCA has also played host to the first American and solo exhibitions of prominent artists such as Frida Kahlo[10] in 1978.[33] Other exhibition highlights include the first solo museum shows of Dan Flavin,[34] in 1967,[33] and Jeff Koons,[35] in 1988.[33] In 1989, the MCA hosted Robert Mapplethorpe, The Perfect Moment, a traveling exhibition organized by the Institute of Contemporary Art in Philadelphia. This exhibition set a record for the highest attendance in the institution's history.[7] Additional highlights of exhibitions organized or co-organized by the MCA include:

|

|

Recent

In 2006, the MCA was the only American museum to host Bruce Mau's Massive Change exhibit, which concerned the social, economic, and political effects of design. Additional 2006 exhibitions featured photographers Catherine Opie and Wolfgang Tillmans as well as Chicago-based cartoonist Chris Ware. The 2008 Koons retrospective broke the attendance record with 86,584 visitors for the May 31 – show of September 21, 2008.[36][37] This was the culminating exhibit of the 2008 fiscal year,[38] which celebrated the 40th anniversary of the museum.[39]

In 2009, the MCA presented Jeremy Deller's exhibition It Is What It Is: Conversations About Iraq. The exhibition was organized by the New Museum, and it was a new commission by the New Museum, New York; the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago; and the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles.[40]

Co-organized by the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and the Wexner Center for the Arts, the MCA presented Luc Tuymans from October 2010 – January 2011.[41] Susan Philipsz: We Shall Be All was presented at the MCA February – June 2011. The Turner Prize-winning artist's sound exhibition featured protest songs and drew from Chicago's labor history.[42] The exhibition Eiko & Koma: Time is Not Even, Space is Not Empty is the first series of stage performances and a gallery exhibition presented at the MCA. The Japanese-born choreographers and dance artists perform and exhibit at the MCA June – November 2011.[43]

Recurring programs

After a 10-year run, the exhibition series UBS 12x12: New Artists/New Work is moving from the second floor to the third floor, into a larger gallery space and will change its name to "Chicago Works." The exhibition series will still feature Chicago-area artists. Rather than each artist being displayed for one month, each exhibition in the series will now be displayed for three months.[44]

Starting in 2002, the MCA began commissioning artists and architects to design and construct public art for the front plaza. The goal of the program is to link the museum to its neighboring community by extending its programmatic, educational, and outreach functions.[45] While artists have been exhibited intermittently on the MCA plaza since 2002, the summer 2011 plaza exhibit showcasing four works by Miami-based sculptor Mark Handforth marks a revitalization of the plaza project.[46]

From October through May, the MCA hosts monthly Family Days, which feature artistic activities for all ages.[47] Each summer, the museum hosts Tuesdays on the Terrace, a jazz performance series; Summer Studios, designed for families to experience the creative process; and a Farmers Market on the MCA plaza on Tuesdays from June through October.[48]

Performance

In 2011, the MCA celebrated its 15th anniversary of the MCA Stage. The MCA Stage has featured local, national, and international theater, dance, music, multimedia, and film performances in its 15-year history. It is known as the "most active interdisciplinary arts presenter in Chicago" and partners with local community organizations for the co-presentations of performing arts.[49]

Notable past stage appearances include performances by Trisha Brown Dance Company, Abbey Theatre of Ireland, Olafur Arnalds, and Elevator Repair Service.[50]

New structure

The new five-storey limestone and cast-aluminum structure was designed by Berlin architect Josef Paul Kleihues. The building, which opened in 1996, contains 45,000 square feet (4,200 m2) of gallery space (seven times the space of the old museum), a theater, studio-classrooms, an education center, a museum store, a restaurant-café, and a sculpture garden.[10][51] The MCA building was Kleihues's first American structure. Its construction cost US$46.5 million ($70.3 million today).[52] The sculpture garden, which is 34,000 square feet (3,200 m2),[17] includes a sculptural installation by Sol LeWitt and sculptures by George Rickey and Jane Highstein. The floor plan of both the building and the sculpture garden is a square, on which the proportions of the building is based.[53]

The building's main entrance, which is accessed by scaling 32 steps, uses both symmetry and transparency as themes for its large central glass walls that compose the majority of both the east and west façades of the building. Two additional entrances—into the education center and into the museum store—are located on either side of the main staircase. The monumental staircase with projecting bays and plinths that may be used as the base for sculpture is reminiscent of the propyleia of the Acropolis in Athens.[53] The main level entry hall has an adjacent 55-foot (16.8 m) atrium that connects it to a restaurant in the rear of the building. Two galleries for temporary exhibitions flank the atrium. The stairwell in the northwest corner is often cited as the buildings most interesting and dynamic artistic feature. The elevated views of Lake Michigan are considered to be a rewarding feature of the building.[32] The building's 56-foot (17.1 m) glass facade sits atop 16 feet (4.9 m) of Indiana limestone.[54] The building is known for its hand-cast aluminum panels adjoined to the facade with stainless steel buttons.[32][54] The building has two two-story gallery spaces and a smaller one-story gallery space on the second floor. The third floor has a gallery and exhibition space in its northwest section, and the fourth floor has two large galleries, an exhibition space on the west side of the building, and a gallery in the southwest section.[32][54]

The museum has a 296-seat multi-use theater with a proscenium-layout stage. The seats are laid out in 14 rows with two side aisles. The stage is 52 by 34 feet (16 m × 10 m) and elevated 36 inches (0.91 m) above the floor level of the first row of seats. The house has a 12 degree incline. The stage has three curtains and four catwalks.[55]

Critical review

Complaining that the structure has a more fortress-like exterior than its predecessor, Kamin viewed the architectural attempt as a fumbled work. However, he considered the interior to be serene and contemplative in a manner that complements the contemporary art and compact and organized in a manner that is an improvement on the more traditional mazelike museums.[32] Comparing the building to the Sullivan Center and the Art Institute of Chicago Building, Kamin describes the museum as an homage to two of Chicago's architectural influences: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Louis Sullivan.[32] Other critics also note the presence of Mies van der Rohe's spirit in the architecture.[56]

Chicago-based architect Douglas Garofalo has described the building as stark, intimidating and "incongruous with contemporary sensibilities".[45] The interior atrium, which the architect claims links the city to the lake is part of a transcendent space that benefits from the sunlight that enters through the high glass walls. The building is said to be designed to separate the art from other distracting services and functions of the venue.[56] Kamin was also pleased with the separate entrances on the main floor for the museum store and accessibility entrances.[32]

New Vision

Announced by the Chicago Tribune in June 2011, the MCA is in the process of reinventing its identity with new curators, a new floor plan, and a new vision. MCA Director Madeleine Grynsztejn says the museum seeks to be 50/50 artist-activated/audience-engaged. The main floor's north and south galleries will present exhibitions showcasing the museum's permanent collection and work by post-emerging contemporary artists. The third floor will be for the "Chicago Works" series. The fourth floor will have gallery spaces for the MCA Screen and MCA DNA series, while the main barrel-vaulted galleries will be for special exhibitions.[57]

Collection

Four Boomerangs, by Alexander Calder, 1949  In Memory of My Feelings - Frank O'Hara, by Jasper Johns, 1995 |

The museum's collection consists of about 2,700 objects, as well as more than 3,000 artist's books. The collection includes works of art from 1945 to the present.[58]

Former MCA Chief Curator Elizabeth Smith provided a narrative of the museum's collection.[59] She says the collection has examples of late surrealism, pop art, minimalism, and conceptual art from the 1940s through the 1970s; work from the 1980s that can be grouped under postmodernism; and painting, sculpture, photography, video, installation, and related media current artists explore.[60]

Notable Works

- Study for a Portrait, 1949, by Francis Bacon

- Les merveilles de la nature (The Wonders of Nature), 1953, René Magritte[61]

- Polychrome and Horizontal Bluebird, 1954, by Alexander Calder

- In Memory of My Feelings - Frank O'Hara, 1961, by Jasper Johns

- Retroactive II, 1963, by Robert Rauschenberg

- Jackie Frieze, 1964, by Andy Warhol[62]

- Untitled, 1970, Donald Judd

- Untitled Film Still, #14, 1978, by Cindy Sherman[63]

- Rabbit, 1986, by Jeff Koons[64]

- Cindy, 1988, by Chuck Close[65]

- Presenting Negro Scenes Drawn Upon My Passage through the South and Reconfigured for the Benefit of Enlightened Audiences Wherever Such May Be Found, By Myself, Missus K.E.B. Walker, Colored, 1997, by Kara Walker[66][67]

During the 2008 fiscal year the MCA celebrated its 40th anniversary, which inspired gifts of works by artists such as Dan Flavin, Alfredo Jaar, and Thomas Ruff. Additionally, the museum expanded its collection by acquiring the work of some of the artists it presented during its anniversary celebration such as Carlos Amorales, Tony Oursler, and Adam Pendleton.[39]

See also

- Chicago architecture

- Visual arts of Chicago

- List of museums and cultural institutions in Chicago

- Museum of Contemporary Art (disambiguation)

- MCA Stage

References

- ↑ "1996". Museum of Contemporary Art. Retrieved August 26, 2015.

- ↑ "The success that David Bowie was at MCA". Crain's Chicago Business. January 6, 2015. Retrieved August 26, 2015.

- ↑ AreaG2 Address- Museum of Contemporary Art

- ↑ "The Architect Joseph Paul Kleihues". Museum of Contemporary Art. Retrieved July 22, 2011.

- 1 2 3 "History of the MCA". Museum of Contemporary Art. Retrieved July 22, 2011.

- ↑ "Museums: Contemporary in Chicago". Time. November 3, 1967. Retrieved October 15, 2009.

- 1 2 3 Museum of Contemporary Art Website. "History of the MCA". Retrieved December 21, 2006.

- ↑ Grimes, William (May 6, 2010). "Jan van der Marck, Museum Administrator, Dies at 80". New York Times. Retrieved July 22, 2011.

- ↑ Mercedes Vostell, Vostell – ein Leben lang, Siebenhaar Verlag, 2012, ISBN 978-3-936962-88-8.

- 1 2 3 4 Kirshner, Judith Russi. "Museum of Contemporary Art". Encyclopedia of Chicago. Chicago Historical Society. Retrieved August 21, 2009.

- ↑ "Gordan Matta-Clark: You Are the Measure". Artdaily. 2008. Retrieved June 13, 2011.

- ↑ "Trustees lead effort to build art museum". Chicago Sun-Times. January 30, 1991. Retrieved August 23, 2009.

- 1 2 Gillespie, Mary (January 29, 1991). "Trustees endow success of a new art museum". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved August 23, 2009.

- ↑ Gillespie, Mary (January 29, 1991). "Donors cite need for new art museum". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved August 23, 2009.

- ↑ Kamin, Blair (January 29, 1991). "Museum Shuns City Architects". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved August 23, 2009.

- ↑ Eds. Grossman, James R., Keating, Ann Durkin, and Reiff, Janice L., 2004 Encyclopedia of Chicago, p. 39. The University of Chicago Press, ISBN 0-226-31015-9

- 1 2 Bianchi, Laura (July 1, 1996). "'Noble and modest' - That was the architect's vision for the new Museum of Contemporary- Art . Even by his own modest account, he has succeeded". Daily Herald. Retrieved May 16, 2009.

- ↑ Artner, Alan G. (June 30, 1996). "Bigger Not Better - 10 Years In Coming, The New MCA Shows More Of The Same Presentations". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved May 16, 2009.

- ↑ Holg, Garrett (December 29, 1996). "Wonder walls - New museum , fascinating shows mark year in art". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved May 16, 2009.

- ↑ "About the MCA". Museum of Contemporary Art. Retrieved September 17, 2009.

- ↑ "Museum of Contemporary Art Annual Report Fiscal Year 2009:Board of Trustees". Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago. Retrieved July 22, 2011.

- ↑ "Museum of Contemporary Art Annual Report Fiscal Year 2009:Letter From The Chair". Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago. Retrieved July 22, 2011.

- ↑ "Museum of Contemporary Art Annual Report Fiscal Year 2008:Letter From The Director". Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago. Retrieved September 16, 2009.

- ↑ "2014 Annual Report" (PDF). Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago. Retrieved August 26, 2015.

- ↑ "Teresa Samala de Guzman named Chief Operating Office at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago". ArtDaily. Retrieved August 26, 2015.

- ↑ "Museum of Contemporary Art Annual Report Fiscal Year 2009:Financial Information". Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago. Retrieved July 22, 2011.

- ↑ "Museum of Contemporary Art Annual Report Fiscal Year 2008:A Year of Support". Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago. Retrieved September 17, 2009.

- ↑ "General Visitor Information". Museum of Contemporary Art. Retrieved July 22, 2011.

- ↑ "Tuesdays on the Terrace". Museum of Contemporary Art. Retrieved September 17, 2009.

- ↑ "First Fridays". Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago. Retrieved July 22, 2011.

- ↑ "Museum of Contemporary Art Annual Report Fiscal Year 2008:Performance Report". Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago. Retrieved September 17, 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Kamin, Blair (2001). "A Fumbled Chance At Greatness:The Museum of Contemporary Art Tries but Fails To Extend Chicago's History of Design Triumphs". Why architecture matters: lessons from Chicago. University of Chicago Press. pp. 142–145. ISBN 978-0-226-42321-0.

- 1 2 3 "History of the MCA". Museum of Contemporary Art. Retrieved February 6, 2007.

- ↑ His first solo show was at the Judson Gallery, New York, in 1961. (Diacenter.org)

- ↑ His first solo exhibition was a 1980 window installation at the New Museum of Contemporary Art in New York

- ↑ Conrad, Marissa (December 2008). "The Innovator". Chicago Social. Chicago, Illinois: 140.

- ↑ "Jeff Koons". Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago. Retrieved January 13, 2009.

- ↑ "Museum of Contemporary Art Annual Report Fiscal Year 2008:2008 Exhibition list". Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago. Retrieved September 16, 2009.

- 1 2 "Museum of Contemporary Art Annual Report Fiscal Year 2008:Curatorial Report". Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago. Retrieved September 16, 2009.

- ↑ "It Is What It Is: Conversations About Iraq". The New Museum and Creative Time for the Three M Project. Retrieved July 22, 2011.

- ↑ "Luc Tuymans". Museum of Contemporary Art. Retrieved July 22, 2011.

- ↑ Wolff, Rachel (February 1, 2011). "Susan Philipsz's 'We Shall Be All' Opens at MCA". Chicago Magazine. Retrieved July 22, 2011.

- ↑ "Eiko & Koma Open Live Exhibition". Eiko & Koma. Retrieved July 22, 2011.

- ↑ Viera, Lauren (June 10, 2011). "MCA 2.0". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved August 5, 2011.

- 1 2 Garofalo, Douglas (2003). Between the museum and the city. Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago. pp. 11–18. ISBN 978-0-933856-82-0. Retrieved October 18, 2009.

- ↑ Thomas, Mike (July 7, 2011). "Museum of Contemporary Art hopes artist can liven up the building". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved July 22, 2011.

- ↑ "Family Days". Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago. Retrieved August 5, 2011.

- ↑ "Events and Activities". Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago. Retrieved August 5, 2011.

- ↑ "2011-2012 MCA Stage Season" (PDF). Press Release. Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago. May 19, 2011. Retrieved July 7, 2011.

- ↑ "Past Performances". Museum of Contemporary Art. Archived from the original on September 15, 2011. Retrieved July 22, 2011.

- ↑ "The Building". Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago. Retrieved August 10, 2011.

- ↑ Rodkin, Dennis (June 30, 1996). "Plants Act As Colorful 'Gallery' Walls For Sculpture In New MCA Garden". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved May 16, 2009.

- 1 2 Naredi-Rainer, Paul von (2004). A Design Manual: Museum Buildings. Birkhäuser. Retrieved August 5, 2011.

- 1 2 3 McBrien, Judith Paine (2004). "Museum of Contemporary Art". Pocket guide to Chicago architecture. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-393-73155-2.

- ↑ "Technical Overview". Museum of Contemporary Art. Retrieved September 17, 2009.

- 1 2 LeBlanc, Sydney (2000). The architecture traveler: a guide to 250 key 20th century American buildings. W.W. Norton & Company. p. 224. ISBN 978-0-393-73050-0.

- ↑ Viera, Lauren (June 10, 2011). "MCA 2.0". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved August 5, 2011.

- ↑ Museum of Contemporary Art Website. "MCA Collection Highlights". Retrieved May 16, 2009.

- ↑ Smith, Elizabeth (2003). "Life Death Love Hate Pleasure Pain: Selected Works from the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago". Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago. Retrieved May 16, 2009.

- ↑ "Life Death Love Hate Pleasure Pain: Selected Works from the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago". Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago. 2005. Archived from the original on October 25, 2008. Retrieved May 16, 2009.

- ↑ "Magritte, René". Museum of Contemporary Art. Retrieved August 5, 2011.

- ↑ "Warhol, Andy". Museum of Contemporary Art. Retrieved August 5, 2011.

- ↑ "Sherman, Cindy". Museum of Contemporary Art. Retrieved August 5, 2011.

- ↑ "Koons, Jeff". Museum of Contemporary Art. Retrieved August 5, 2011.

- ↑ "Close, Chuck". Museum of Contemporary Art. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved February 5, 2007.

- ↑ "Walker, Kara". Museum of Contemporary Art. Retrieved August 5, 2011.

- ↑ Smith, Elizabeth. Life Death Love Hate Pleasure Pain: Selected works from the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago. Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago: 2003.

External links

Coordinates: 41°53′50″N 87°37′16″W / 41.8972°N 87.6212°W