Raghnall Mac Ruaidhrí

| Raghnall Mac Ruaidhrí | |

|---|---|

| |

| Predecessor | Ruaidhrí Mac Ruaidhrí |

| Successor | Áine Nic Ruaidhrí |

| Noble family | Clann Ruaidhrí |

| Father | Ruaidhrí Mac Ruaidhrí |

| Died |

October 1346 Elcho Priory |

Raghnall Mac Ruaidhrí (died October 1346) was an eminent Scottish magnate and chief of Clann Ruaidhrí.[note 2] Raghnall's father, Ruaidhrí Mac Ruaidhrí, appears to have been slain in 1318, at a time when Raghnall may have been under age. Ruaidhrí himself appears to have faced resistance over the Clann Ruaidhrí lordship from his sister, Cairistíona, wife Donnchadh, son of the Earl of Mar. Following Ruaidhrí's demise, there is evidence indicating that Cairistíona and her powerful confederates also posed a threat to the young Raghnall. Nevertheless, Raghnall eventually succeeded to his father, and first appears on record in 1337.

Raghnall's possession of his family's expansive ancestral territories in the Hebrides and West Highlands put him in conflict with the neighbouring magnate William III, Earl of Ross, and contention between the two probably contributed to Raghnall's assassination at the hands of the earl's adherents in 1346. Following his death, the Clann Ruaidhrí territories passed through his sister, Áine, into the possession of her husband, the chief of Clann Domhnaill, Eóin Mac Domhnaill, resulting in the latter's consolidation of power in the Hebrides as Lord of the Isles.

Clann Ruaidhrí

.png)

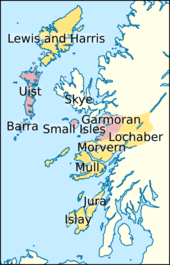

Raghnall was an illegitimate son of Ruaidhrí Mac Ruaidhrí (died 1318?),[9] grandson of the eponymous ancestor of Clann Ruaidhrí.[10] The identity of Raghnall's mother is unknown.[9] Raghnall's father controlled a provincial lordship which encompassed the mainland territories of Moidart, Arisaig, Morar, and Knoydart; and the island territories of Rhum, Eigg, Barra, St Kilda, and Uist.[9] This dominion, like the great lordships of Annandale and Galloway, was comparable to the kingdom's thirteen earldoms.[11] There is reason to suspect that the rights to the family's territories were contested after Ruaidhrí's death.[12] In fact, Ruaidhrí himself was illegitimate, and only gained formal control of the lordship after his legitimate half-sister, Cairistíona (fl. 1290–1318), resigned her rights to him at some point during the reign of Robert I, King of Scotland (died 1329).[13][note 3]

Raghnall's father appears to be identical to the Clann Ruaidhrí dynast, styled "King of the Hebrides", who lost his life in the service of the Bruce campaign in Ireland in 1318.[17] At the time, Raghnall may well have been under age, and it is apparent that Cairistíona and her confederates again attempted to seize control of the inheritance.[18] Although she is recorded to have resigned her claimed rights to a a certain Artúr Caimbéal at some point after Ruaidhrí's death,[19] it is clear that Raghnall succeeded in securing the region, and was regarded as the chief of Clann Ruaidhrí by most of his kin.[20][note 4]

.png)

In 1325, a certain "Roderici de Ylay" suffered the forfeiture of his possessions by Robert I.[28] Although this record could refer to a member of Clann Ruaidhrí, and evidence the contrast of relations between Clann Ruaidhrí and the Scottish Crown in the 1320s and 1330s,[29] another possibility is that the individual actually refers to a member of Clann Domhnaill.[30] If this indeed refers to a member of the former family, the man in question may well have been Raghnall himself. If so, it is conceivable that his forfeiture is related to Cairistíona's attempt to alienate the Clann Ruaidhrí estate from her nephew and transfer it into the clutches of the Caimbéalaigh kindred.[31] Alternately, the forfeiture could have been ratified in response to undesirable Clann Ruaidhrí expansion into certain neighbouring regions, such as the former territories of the disinherited Clann Dubhghaill.[32]

Although Cairistíona's resignation charter to Artúr is undated,[33] it could date to just before the forfeiture.[34][note 5] The list of witnesses who attested this grant is remarkable, and may reveal that the charter had royal approval.[36] The witnesses include: John Menteith, Domhnall Caimbéal, Alasdair Mac Neachdainn, Eóghan Mac Íomhair, Donnchadh Caimbéal (son of Tomás Caimbéal), Niall Mac Giolla Eáin, and (the latter's brother) Domhnall Mac Giolla Eáin. These men all seem to have been close adherents of Robert I against Clann Dubhghaill, and all represented families of power along the western seaboard. An alliance of such men may well have been an intimidating prospect to the Clann Ruaidhrí leadership.[37] In fact, the forfeiture could have been personally reinforced by Robert I, as the king seems to have travelled to Tarbert Castle—a royal stronghold in Kintyre—within the same year.[38][note 6]

Career

This Raynald menyd wes gretly,

For he wes wycht man and worthy.

And fra men saw this infortown,

Syndry can in thare hartis schwne,

And cald it iẅill forbysnyng,

That in the fyrst off thare steryng

That worthy man suld be slayne swa,

And swa gret rowtis past thaim fra.

— excerpt from the Orygynale Cronykil of Scotland depicting the royal army's consternation at the assassination of Raghnall ("Raynald") by adherents of the William III, Earl of Ross.[40]

Unlike the First War of Scottish Independence, in which Clann Ruaidhrí participated, Raghnall and his family are not known to have taken part in the second war (from 1332–41).[41] In fact, Raghnall certainly appears on record by 1337,[42] when he aided his third cousin, Eóin Mac Domhnaill, Lord of the Isles (died c. 1387), in the latter's efforts to receive a papal dispensation to marry Raghnall's sister, Áine (fl. 1318–1350), in 1337.[43][note 7] At the time, Raghnall and Eóin were apparently supporters of Edward Balliol (died 1364),[45] a claimant to the Scottish throne who held power in the realm from 1332 to 1336.[46] By June 1343, however, both Raghnall and Eóin were reconciled with Edward's rival, the reigning son of Robert I, David II, King of Scotland (died 1371),[47] and Raghnall himself was confirmed in the Clann Ruaidhrí lordship by the king.[48][note 8]

At about this time, Raghnall received the rights to Kintail from William III, Earl of Ross (died 1372), a transaction which was confirmed by the king that July.[54] There is reason to suspect that the king's recognition of this grant may have been intended as a regional counterbalance of sorts, since he also diverted the rights to Skye from Eóin to William III.[55] It is also possible that Clann Ruaidhrí power had expanded into the coastal region of Kintail at some point after the death of William III's father in 1333, during a period when William III may have been either a minor or exiled from the country. Whatever the case, the earl seems to have had little choice but to relinquish his rights to Kintail to Raghnall.[56]

Bitterness between these two magnates appears to be evidenced in dramatic fashion by the assassination of Raghnall and several of his followers at the hands of the earl and his adherents.[57] Raghnall's murder unfolded at at Elcho Priory in October 1346,[58] and is attested by numerous sources, such as the fifteenth-century Scotichronicon,[59] the fifteenth-century Orygynale Cronykil of Scotland,[60] the fifteenth-century Liber Pluscardensis,[61] and the seventeenth-century Sleat History.[62] At the time of his demise, Raghnall had been obeying the king's muster at Perth, in preparation for the Scots' imminent invasion of England. Following the deed, William III deserted the royal host, and fled to the safety of his domain.[63] What is known of William III's comital career reveals that it was local, rather than national issues, that laid behind his recorded actions. The murder of Raghnall and the earl's desertion—a flight which likely left his king with a substantially smaller fighting-force—is one such example.[64] Although William III was later to pay dearly for this act of disloyalty,[65] the episode itself evidences the earl's determination to deal with the threat of encroachment of Clann Ruaidhrí power into what he regarded as his own domain.[66] Despite this dramatic removal of William III's main rival, the most immediate beneficiary of the killing was Eóin,[67] the chief of Clann Domhnaill, a man who was also William III's brother-in-law.[68]

Following Raghnall's death, control of the Clann Ruaidhrí estate passed to Eóin by right of his wife.[70] Although Áine appears to have been either dead or divorced from Eóin by 1350, the Clann Ruaidhrí territories evidently remained in Eóin's possession after his subsequent marriage to Margaret, daughter of Robert Stewart, Steward of Scotland (died 1390).[71][note 9] David himself died in 1371, and was succeeded by his uncle, Robert Stewart (as Robert II).[75] In 1372, the recently-crowned king confirmed Eóin's rights to the former Clann Ruaidhrí territories.[76] The year after that, Robert II confirmed Eóin's grant of these lands to Raghnall Mac Domhnaill (died 1386)—Eóin and Áine's eldest surviving son[77]—a man apparently named after Raghnall himself.[12][note 10]

Raghnall seems to have had a brother, Eóghan, who received a grant to the thanage of Glen Tilt from the Steward.[80] The transaction appears to date to before 1346,[81] at about the time members of Clann Ruaidhrí were operating as gallowglasses in Ireland.[82] This could in turn indicate that the Steward was using the kindred in a military capacity to extend his own power eastwards into Atholl,[83] where he appears to have also made use of connections with Clann Donnchaidh.[84][note 11] If certain fifteenth-century pedigrees are two be believed, Raghnall had at least one illegitimate son, and his descendants continued to act as leaders of Clann Ruaidhrí.[12][note 12]

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Raghnall Mac Ruaidhrí | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes

- ↑ The island the fortress sits upon is first recorded in a charter of Raghnall's aunt, Cairistíona Nic Ruaidhrí. Following Raghnall's death, the site passed to Clann Domhnaill through his sister, Áine (fl. 1318–50), and came to be held by descendants of her son, Raghnall Mac Domhnaill (died 1386), for about four hundred years.[2]

- ↑ Since the 1980s, academics have accorded Raghnall various patronymic names in English secondary sources: Raghnall Mac Ruaidhri,[3] Ranald MacRuairi,[4] Ranald MacRuari,[5] Ranald Macruairi,[6] Ranald MacRuarie,[7] Ranald MacRuaridh.[8]

- ↑ Cairistíona's claims to the Clann Ruaidhrí inheritance apparently posed a potential threat to Ruaidhrí and Raghnall. For example, Cairistíona was the wife of Donnchadh, son of Domhnall I, Earl of Mar (died ×1297). The latter's daughter, Iseabail, was in turn the first wife of Robert I; and Domhnall I's son and comital successor, Gartnait (died c. 1302), was the husband of a sister of Robert I. Furthermore, Cairistíona and Donnchadh had a son, Ruaidhrí, who potentially could have sought royal assistance in pursuance of his mother's claims.[14] The fact that the latter had been bestowed the name Ruaidhrí could indicate that he was not only named after his maternal grandfather, but that he was regarded as a potential successor to the Clann Ruaidhrí lordship.[15] Certainly, Cairistíona resigned her claims with the condition that if her brother died without a male heir, her like-named son would secure the inheritance.[16]

- ↑ One possibility is that the scheme between Cairistíona and Artúr had been undertaken in the context of a marital alliance between her and the latter's family, the Caimbéalaigh (the Campbells).[21] Robert I is known to have granted the constableship of the former Clann Dubhghaill stronghold of Dunstaffnage Castle to a certain Artúr Caimbéal. The identity of this constable is uncertain, however, as there was a father and son who bore this name.[22] Whilst the constableship may have been awarded to the senior-most Artúr,[23] Cairistíona's transaction appears to have involved his son,[24] and it is possible that the latter was intended to marry her.[25] Whatever the case, the elder Artúr seems to be the founding ancestor of the Strachur branch of the Caimbéalaigh.[26]

- ↑ The fact that she is called a widow, and is not named "of Mar", appears to be evidence that it dates to after her husband's death.[35]

- ↑ The brothers Niall Mac Giolla Eáin and Domhnall Mac Giolla Eáin, along with another brother, Eóin Mac Giolla Eáin, are associated with the castle at about this time.[39]

- ↑ Early modern tradition preserved by the Sleat History, claims that Raghnall's sister (described as "Algive", daughter of "Allan, son of Roderick Macdougall") cohabited with Eóin for nine or ten years.[44]

- ↑ Although the expansive Clann Ruaidhrí territories are often regarded as a single "Lordship of Garmoran", this title is a modern construct, and the region of Garmoran was actually just one of several mainland territories ruled by the kindred.[49] In fact, the notice of the king's grant of lands to Raghnall in 1343 preserves the earliest instance of the place name ("Garw Morwarne").[50] In 1336, Edward granted Eóin a large swathe of territory in Argyll and the Hebrides for undertaking to oppose Edward's enemies. Specifically, the grant included the islands of Colonsay, Gigha, Islay, (half of) Jura, Lewis and Harris, Mull, Skye, and the mainland territories of Ardnamurchan, Kintyre, Knapdale, and Morvern. This allotment, therefore, included regions formerly held by apparent supporters of David II, Clann Dubhghaill and Clann Ruaidhrí.[51] Whatever the case, the subsequent eclipse of the Balliol regime, and the return of David II to the throne, rendered Eóin's extensive grant redundant.[52]

- ↑ Negotiations concerning the marriage between Eóin and Margaret may have commenced not long after Raghnall's demise,[72] and could have involved the Steward's recognition of Eóin's continued possession of the Clann Ruaidhrí lands.[73] According to the Sleat History, Eóin abandoned Áine "by the consent of his council and familiar friends".[74]

- ↑ The grant of the former Clann Ruaidhrí territories to Raghnall Mac Domhnaill may well have been in compensation for his exclusion from the chiefship of Clann Domhnaill, which fell to the eldest son of Eóin and Margaret.[78] Raghnall Mac Domhnaill went on to become the eponymous ancestor of the Clann Raghnaill branch of Clann Domhnaill.[79]

- ↑ The Steward's charter to Eóghan identifies him as a brother of Raghnall "of the Isles". Although it is possible that this Eóghan represents yet another son of Eóin, and that this Raghnall represents Raghnall Mac Domhnaill, that fact that the latter was probably only a teenager at the time, coupled with the fact Eóghan is not described as a son of Eóin, suggests that the charter does not concern Clann Domhnaill at all. Certainly, leading members of Clann Ruaidhrí are known to have styled themselves de Insulis.[85] A particular Gaelic ballad concerning the legendary Diarmaid Ó Duibhne may further cast light on Clann Ruaidhrí following Raghnall's death. The poem itself appears to have been composed around Glen Shee in about 1400 by a certain Ailéan Mac Ruaidhrí, a man who could have been a descendant of Eóghan.[86] The Irish version of the poem is centred in Sligo, a region where Clann Ruaidhrí gallowglasses are known to have settled in the fourteenth century.[87]

- ↑ The fact that Clann Ruaidhrí continued on into later centuries is evidenced by the fifteenth-century executions of Alasdair Mac Ruaidhrí (died 1428) and Eóin Mac Artair (died 1428), chieftains said to have commanded one thousand men apiece.[88] These two may have been continuing a feud that stemmed from Cairistíona's contested inheritance and connections with the Caimbéalaigh.[89] The Artúr Caimbéal whom Cairistíona granted the Clann Ruaidhrí lordship was himself the son of another Artúr Caimbéal, a man closely aligned with Robert I.[90]

Citations

- ↑ Tabraham (2005) pp. 29, 111.

- ↑ Stell (2014); Addyman; Oram (2012); Fisher (2005) pp. 91, 94.

- ↑ Nicholls (2007).

- ↑ Penman, MA (2014); Webster (2011); Caldwell (2008); Proctor (2006); Brown, M (2004); Boardman, SI (2004); Roberts (1999).

- ↑ Cochran-Yu (2015); Addyman; Oram (2012); Campbell of Airds (2000); Duncan (1998); Boardman, S (1997); Boardman, S (1996a); Boardman, S (1996b); Munro (1986).

- ↑ Daniels (2013).

- ↑ Penman, MA (2001).

- ↑ Penman, M (2014); Munro; Munro (2008); Penman, MA (2005); Oram (2004).

- 1 2 3 Daniels (2013) p. 94; Boardman, SI (2004).

- ↑ Bannerman (1998) p. 25.

- ↑ McNamee (2012) ch. 1.

- 1 2 3 Boardman, SI (2004).

- ↑ Boardman, S (2006) pp. 46, 54 n. 52, 55 n. 61; Ewan (2006); Raven (2005) p. 63; Boardman, SI (2004); Brown, M (2004) p. 263; Barrow (1988) pp. 290–291; Thomson, JM (1912) pp. 428–429 § 9; MacDonald; MacDonald (1896) pp. 495–496.

- ↑ Boardman, S (2006) p. 46.

- ↑ Boardman, S (2006) p. 55 n. 61.

- ↑ Boardman, S (2006) p. 55 n. 61; Ewan (2006); Barrow (1988) pp. 290–291.

- ↑ Daniels (2013) p. 94; Boardman, S (2006) pp. 45–46; Annals of Loch Cé (2008) § 1318.7; Annala Uladh (2005) § 1315.5; Annals of Loch Cé (2005) § 1318.7; Annala Uladh (2003) § 1315.5; Duffy (2002) p. 61, 195 n. 64; Barrow (1988) p. 377 n. 103; Steer; Bannerman; Collins (1977) p. 203; Murphy (1896) p. 281.

- ↑ Boardman, S (2006) pp. 45–46; Proctor (2006).

- ↑ Boardman, S (2006) pp. 46–47; Boardman, SI (2005) p. 149 n. 4; Fisher (2005) p. 91; Raven (2005) p. 63; Boardman, SI (2004); Campbell of Airds (2000) pp. 71–72; McDonald (1997) pp. 189–190 n. 120; Barrow (1980) p. 139 n. 110; PoMS, H3/0/0 (n.d.); PoMS Transaction Factoid, No. 79436 (n.d.).

- ↑ Boardman, S (2006) p. 46; Boardman, SI (2004).

- ↑ Campbell of Airds (2004) pp. 142–143; Campbell of Airds (2000) pp. 71–72, 225.

- ↑ Boardman, S (2006) p. 54 n. 56.

- ↑ Boardman, S (2006) p. 45; Campbell of Airds (2004) p. 142; Campbell of Airds (2000) pp. xiv, xviii, 70, 74–75, 225–226.

- ↑ Boardman, S (2006) pp. 46–47; Boardman, SI (2005) p. 149 n. 4; Campbell of Airds (2004) p. 142; Campbell of Airds (2000) pp. 71–72.

- ↑ Campbell of Airds (2004) pp. 142–143; Campbell of Airds (2000) pp. 71–72, 225.

- ↑ Campbell of Airds (2004) p. 142; Campbell of Airds (2000) pp. 70, 74, 225.

- ↑ Birch (1905) p. 135 pl. 20.

- ↑ Penman, M (2014) pp. 259–260, 391 n. 166; Penman, MA (2014) pp. 74–75, 74–75 n. 42; Brown, M (2004) p. 267 n. 18; McDonald (1997) p. 187; Barrow (1988) p. 299; Steer; Bannerman; Collins (1977) p. 203, 203 n. 12; Duncan; Brown (1956–1957) p. 205 n. 9; Thomson, JM (1912) p. 557 § 699; RPS, A1325/2 (n.d.a); RPS, A1325/2 (n.d.b).

- ↑ Penman, M (2014) p. 391 n. 166; Penman, MA (2014) pp. 74–75; Penman, M (2008); Penman, MA (2005) pp. 28, 84.

- ↑ Cameron (2014) pp. 153–154; Penman, MA (2014) pp. 74–75 n. 42; McQueen (2002) p. 287 n. 18; McDonald (1997) p. 187; Steer; Bannerman; Collins (1977) p. 203.

- ↑ Penman, M (2014) pp. 259–260.

- ↑ Penman, M (2008).

- ↑ Boardman, S (2006) p. 55 n. 62.

- ↑ Penman, M (2014) pp. 259–260.

- ↑ Boardman, S (2006) p. 55 n. 62.

- ↑ Penman, M (2014) pp. 259–260.

- ↑ Boardman, S (2006) pp. 46–47.

- ↑ Penman, M (2014) p. 260; Penman, MA (2014) pp. 74–75 n. 42.

- ↑ Penman, M (2014) p. 260; Boardman, S (2006) pp. 47–48; McNeill (1981) pp. 3–4; Origines Parochiales Scotiae (1854) pp. 34–35; Thomson, T (1836) pt. 2 pp. 6–8.

- ↑ Penman, MA (2014) p. 79; Penman, MA (2005) p. 126; Amours (1908) pp. 172–175; MacDonald; MacDonald (1896) p. 502; Laing (1872) p. 472 §§ 6127–6134.

- ↑ Daniels (2013) pp. 25, 94.

- ↑ Daniels (2013) pp. 94–95; Boardman, SI (2004).

- ↑ Penman, MA (2014) p. 77, 77 n. 51; Boardman, SI (2004); Daniels (2013) pp. 94–95; Brown, M (2004) p. 270; Macphail (1914) pp. 25 n. 1, 73–75; Thomson, JM (1911); Stuart (1798) p. 446.

- ↑ Cathcart (2006) p. 101 n. 6; Macphail (1914) p. 25.

- ↑ Daniels (2013) pp. 94–95; Boardman, SI (2004); Penman, MA (2001) p. 166; Boardman, S (1996b) pp. 30–31 n. 60.

- ↑ Webster (2004).

- ↑ Daniels (2013) pp. 94–95; Caldwell (2008) p. 52; Boardman, S (2006) p. 62; Boardman, SI (2004); Penman, MA (2001) p. 166; Boardman, S (1996b) pp. 30–31 n. 60.

- ↑ Penman, MA (2014) p. 77; Daniels (2013) p. 95; Addyman; Oram (2012); Caldwell (2008) p. 52; Boardman, S (2006) p. 87; Raven (2005) pp. 61, 64; Boardman, SI (2004); Penman, MA (2001) p. 166; Campbell of Airds (2000) p. 83; Thomson, JM (1912) p. 569 § 861; MacDonald; MacDonald (1900) p. 743; Robertson (1798) p. 48.

- ↑ Raven (2005) p. 61.

- ↑ Raven (2005) p. 61; Thomson, JM (1912) p. 569 § 861; MacDonald; MacDonald (1900) p. 743; Robertson (1798) p. 48.

- ↑ Daniels (2013) pp. 35, 91, n. 91 n. 287; Boardman, S (2006) pp. 60, 86 n. 31, 86–87 n. 32; Brown, M (2004) pp. 269–270; Oram (2004) p. 124; MacDonald; MacDonald (1896) pp. 496–497; Bain (1887) pp. 213–214 § 1182; Rymer; Holmes (1740) pt. 3 p. 152.

- ↑ Oram (2004) p. 124.

- ↑ The Balliol Roll (n.d.).

- ↑ Penman, MA (2005) p. 99; Boardman, SI (2004); Penman, MA (2001) p. 166; Boardman, S (1996b) p. 101 n. 43; Munro (1986) pp. 59–61; MacDonald; MacDonald (1900) p. 744; Thomson, JM (1912) p. 569 § 860; Robertson (1798) p. 48.

- ↑ Penman, MA (2005) p. 99; Penman, MA (2001) p. 166.

- ↑ Boardman, SI (2004); Boardman, S (1996b) p. 101 n. 43.

- ↑ Daniels (2013) pp. 28, 95, 112; Penman, MA (2005) pp. 99, 126; Boardman, SI (2004); Brown, M (2004) p. 271; Boardman, S (1996b) p. 101 n. 43;.

- ↑ Cochran-Yu (2015) p. 86; Penman, MA (2005) p. 126; Boardman, SI (2004); Brown, M (2004) p. 271.

- ↑ Cochran-Yu (2015) p. 86; Brown, M (2004) p. 271; Oram (2004) p. 124; Goodall (1759) pp. 339–340.

- ↑ Penman, MA (2014) p. 79; Penman, MA (2005) p. 126; Amours (1908) pp. 172–175; MacDonald; MacDonald (1896) p. 502; Laing (1872) pp. 471–472 §§ 6111–6138.

- ↑ Penman, MA (2005) p. 126; Cokayne; White (1949) p. 146 n. d; Skene (1880) p. 223; Skene (1877) p. 229.

- ↑ Penman, MA (2014) p. 79; Penman, MA (2005) p. 126; Macphail (1914) p. 18, 18 n. 1.

- ↑ Cochran-Yu (2015) p. 86; Penman, MA (2014) p. 79; Daniels (2013) p. 112; Webster (2011); Munro; Munro (2008); Penman, MA (2005) pp. 1–2, 99, 126, 158; Brown, M (2004) pp. 247, 271; Oram (2004) p. 124; Penman, MA (2001) pp. 166, 175–176; Duncan (1998) pp. 261, 268; Boardman, S (1997) p. 39; Munro (1986) p. 62; Cokayne; White (1949) p. 146, 146 n. d.

- ↑ Daniels (2013) pp. 28, 112.

- ↑ Daniels (2013) pp. 112–113.

- ↑ Daniels (2013) p. 28.

- ↑ Brown, M (2004) p. 271; Duncan (1998) p. 268.

- ↑ Caldwell (2008) pp. 52–53; Duncan (1998) p. 268.

- ↑ Lynch (1991) p. 65.

- ↑ Stell (2014) p. 273; Daniels (2013) pp. 25, 90–91, 95; Caldwell (2008) p. 52; Boardman, SI (2004); Brown, M (2004) p. 271; Munro; Munro (2004); Oram (2004) p. 124; Duncan (1998) p. 268 n. 6.

- ↑ Proctor (2006); Boardman, SI (2004); Oram (2004) p. 124; Munro (1981) p. 24; Bliss (1897) p. 381; Theiner (1864) p. 294 § 588.

- ↑ Penman, MA (2014) p. 79.

- ↑ Boardman, S (1996b) p. 12.

- ↑ Cathcart (2006) p. 101 n. 6; Macphail (1914) p. 26.

- ↑ Boardman, SI (2006).

- ↑ Cameron (2014) p. 157; Penman, MA (2014) p. 86; Proctor (2006); Penman, MA (2005) p. 158 n. 53; Raven (2005) p. 66; Oram (2004) p. 128; Campbell of Airds (2000) p. 95; Boardman, S (1996b) p. 90; Thomson, JM (1912) pp. 147 § 412, 201 § 551; RPS, 1372/3/15 (n.d.a); RPS, 1372/3/15 (n.d.b).

- ↑ Proctor (2006); Boardman, SI (2004); Boardman, S (1996b) p. 90; Thomson, JM (1912) p. 189 § 520; MacDonald; MacDonald (1896) pp. 502–503.

- ↑ Oram (2004) p. 128.

- ↑ Caldwell (2008) p. 55; Raven (2005) p. 66; Munro; Munro (2004).

- ↑ Boardman, SI (2004); Brown, M (2004) p. 333; Roberts (1999) p. 6; Grant (1998) p. 79; Boardman, S (1996a) pp. 9, 26 n. 46; Boardman, S (1996b) pp. 7, 28 n. 31; Atholl (1908) pp. 26–27.

- ↑ Boardman, S (1996a) p. 9.

- ↑ Annals of the Four Masters (2013a) § 1342.2; Annals of the Four Masters (2013b) § 1342.2; Annála Connacht (2011a) § 1342.3; Annála Connacht (2011b) § 1342.3; Annala Uladh (2005) § 1339.2; McLeod (2005) p. 46; Annala Uladh (2003) § 1339.2; Roberts (1999) p. 8; Boardman, S (1996a) p. 9; AU 1339 (n.d.); Mac Ruaidhri (n.d.); Raid Resulting from Political Encounter (n.d.); The Annals of Connacht, p. 287 (n.d.).

- ↑ Roberts (1999) p. 10; Boardman, S (1996a) p. 9; Boardman, S (1996b) p. 7.

- ↑ Boardman, S (1996a) p. 9; Boardman, S (1996b) p. 7.

- ↑ Boardman, S (1996b) p. 28 n. 31; Atholl (1908) pp. 26–27.

- ↑ Boardman, S (1996a) p. 26 n. 5; Boardman, S (1996b) pp. 106–107 n. 104; M'Lachlan; Skene (1862) pp. (pt. 1) 30–34, (pt. 2) 20–23.

- ↑ Boardman, S (1996a) p. 26 n. 5.

- ↑ Boardman, S (2006) p. 126; Boardman, SI (2005) p. 133; Campbell of Airds (2004) p. 142; Campbell of Airds (2000) pp. 114–116, 226; Brown, MH (1991) pp. 290–291; Watt (1987) p. 261; Hearnius of Airds (1722) pp. 1283–1284.

- ↑ Boardman, S (2006) pp. 126, 137 n. 53; Campbell of Airds (2000) pp. 114–116, 176, 226.

- ↑ Boardman, S (2006) pp. 45–46, 54 n. 56.

- 1 2 3 Brown, M (2004) p. 77 fig. 4.1; Sellar (2000) p. 194 tab. ii.

References

Primary sources

- Amours, FJ, ed. (1908). The Original Chronicle of Andrew of Wyntoun. Vol. 6. Edinburgh: William Blackwood and Sons – via Internet Archive.

- "Annala Uladh: Annals of Ulster Otherwise Annala Senait, Annals of Senat". Corpus of Electronic Texts (28 January 2003 ed.). University College Cork. 2003. Retrieved 16 December 2015.

- "Annala Uladh: Annals of Ulster Otherwise Annala Senait, Annals of Senat". Corpus of Electronic Texts (13 April 2005 ed.). University College Cork. 2005. Retrieved 16 December 2015.

- "Annála Connacht". Corpus of Electronic Texts (25 January 2011 ed.). University College Cork. 2011a. Retrieved 12 April 2016.

- "Annála Connacht". Corpus of Electronic Texts (25 January 2011 ed.). University College Cork. 2011b. Retrieved 12 April 2016.

- "Annals of the Four Masters". Corpus of Electronic Texts (3 December 2013 ed.). University College Cork. 2013a. Retrieved 28 December 2015.

- "Annals of the Four Masters". Corpus of Electronic Texts (16 December 2013 ed.). University College Cork. 2013b. Retrieved 28 December 2015.

- "Annals of Loch Cé". Corpus of Electronic Texts (13 April 2005 ed.). University College Cork. 2005. Retrieved 16 December 2015.

- "Annals of Loch Cé". Corpus of Electronic Texts (5 September 2008 ed.). University College Cork. 2008. Retrieved 16 December 2015.

- Atholl, J, ed. (1908). Chronicles of the Atholl and Tullibardine Families. Vol. 1. Edinburgh – via Internet Archive.

- Bain, Joseph, ed. (1887). Calendar of Documents Relating to Scotland. Vol. 3, A.D. 1307–1357. Edinburgh: H.M. General Register House – via Internet Archive.

- Bliss, WH, ed. (1897). Calendar of Entries in the Papal Registers Relating to Great Britain and Ireland. Vol. 3. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office – via Internet Archive.

- Goodall, W, ed. (1759). Joannis de Fordun Scotichronicon cum Supplementis ac Continuatione Walteri Boweri. Vol. 2. Edinburgh: Roberti Flaminii – via HathiTrust.

- Hearnius, T, ed. (1722). Johannis de Fordun Scotichronici. Vol. 4. Oxford – via Google Books.

- Laing, D, ed. (1872). Andrew of Wyntoun's Orygynale Cronykil of Scotland. The Historians of Scotland (series vol. 3). Vol. 2. Edinburgh: Edmonston and Douglas – via Internet Archive.

- MacDonald, A; MacDonald, A (1896). The Clan Donald. Vol. 1. Inverness: The Northern Counties Publishing Company – via Internet Archive.

- MacDonald, A; MacDonald, A (1900). The Clan Donald. Vol. 2. Inverness: The Northern Counties Publishing Company – via Internet Archive.

- Macphail, JRN, ed. (1914). Highland Papers. Publications of the Scottish History Society, Second Series (series vol. 5). Vol. 1. Edinburgh: Scottish History Society – via Internet Archive.

- M'Lachlan, T; Skene, WF, eds. (1862). The Dean of Lismore's Book: A Selection of Ancient Gaelic Poetry. Edinburgh: Edmonston and Douglas – via Internet Archive.

- Murphy, D, ed. (1896). The Annals of Clonmacnoise. Dublin: Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland – via Internet Archive.

- Origines Parochiales Scotiae: The Antiquities, Ecclesiastical and Territorial, of the Parishes of Scotland. Vol. 2 (pt. 1). Edinburgh: W.H. Lizars. 1854 – via Internet Archive.

- "PoMS, H3/0/0". People of Medieval Scotland, 1093–1314. n.d. Retrieved 19 December 2015.

- "PoMS Transaction Factoid, No. 79436". People of Medieval Scotland, 1093–1314. n.d. Retrieved 19 December 2015.

- Robertson, W, ed. (1798). An Index Drawn Up About the Year 1629, of Many Records of Charters, Granted by the Different Sovereigns of Scotland Between the Years 1309 and 1413. Edinburgh: Murray & Cochrane – via Internet Archive.

- "RPS, A1325/2". The Records of the Parliaments of Scotland to 1707. n.d.a. Retrieved 27 November 2015.

- "RPS, A1325/2". The Records of the Parliaments of Scotland to 1707. n.d.b. Retrieved 27 November 2015.

- "RPS, 1372/3/15". The Records of the Parliaments of Scotland to 1707. n.d.a. Retrieved 27 November 2015.

- "RPS, 1372/3/15". The Records of the Parliaments of Scotland to 1707. n.d.b. Retrieved 27 November 2015.

- Rymer, T; Holmes, G, eds. (1740). Fœdera, Conventiones, Litteræ, Et Cujuscunque Generis Acta Publica, Inter Reges Angliæ, Et Alios Quosvis Imperatores, Reges, Pontifices, Principes, Vel Communitates. Vol. 2 (pts. 3–4). The Hague: Joannem Neaulme – via Internet Archive.

- Skene, FJH, ed. (1877). Liber Pluscardensis. The Historians of Scotland (series vol. 7). Vol. 1. Edinburgh: William Paterson – via Internet Archive.

- Skene, FJH, ed. (1880). The Book of Pluscarden. The Historians of Scotland (series vol. 10). Vol. 2. Edinburgh: William Paterson – via Internet Archive.

- "Source Name / Title: AU 1339 [1342], p. 467". The Galloglass Project. n.d. Retrieved 12 April 2016.

- "Source Name / Title: The Annals of Connacht (AD 1224–1544), ed. A. Martin Freeman (Dublin: The Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 1944), p. 287". The Galloglass Project. n.d. Retrieved 12 April 2016.

- Stuart, A (1798). Genealogical History of the Stewarts. London: A. Strahan – via Internet Archive.

- "The Balliol Roll". The Heraldry Society of Scotland. n.d. Retrieved 24 December 2015.

- Theiner, A, ed. (1864). Vetera Monumenta Hibernorum et Scotorum Historiam Illustrantia. Rome: Vatican – via HathiTrust.

- Thomson, JM (1911). "The Dispensation for the Marriage of John Lord of the Isles and Amie Mac Ruari, 1337". Scottish Historical Review. 8 (31): 249–250. eISSN 1750-0222. ISSN 0036-9241. JSTOR 25518321 – via JSTOR. (subscription required (help)).

- Thomson, JM, ed. (1912). Registrum Magni Sigilli Regum Scotorum: The Register of the Great Seal of Scotland, A.D. 1306–1424 (New ed.). Edinburgh: H.M. General Register House – via HathiTrust.

- Thomson, T, ed. (1836), The Accounts of the Great Chamberlains of Scotland, Vol. 1, Edinburgh – via Internet Archive

- Watt, DER, ed. (1987). Scotichronicon. Vol. 8. Aberdeen: Aberdeen University Press. ISBN 0-08-034527-1 – via Google Books.

Secondary sources

- Addyman, T; Oram, R (2012). "Mingary Castle Ardnamurchan, Highland: Analytical and Historical Assessment for Ardnamurchan Estate". Mingarry Castle Preservation and Restoration Trust. Retrieved 27 November 2015.

- Bannerman, J (1998) [1993]. "MacDuff of Fife". In Grant, A; Stringer, KJ. Medieval Scotland: Crown, Lordship and Community. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. pp. 20–38. ISBN 0 7486 1110 X.

- Barrow, GWS (1980). The Anglo-Norman Era in Scottish History. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-822473-7.

- Barrow, GWS (1988) [1965]. Robert Bruce & the Community of the Realm of Scotland (3rd ed.). Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 0 85224 539 4.

- "Battle / Event Title: Raid Resulting from Political Encounter". n.d. Retrieved 12 April 2016.

- Birch, WDG (1905). History of Scottish Seals. Vol. 1, The Royal Seals of Scotland. Stirling: Eneas Mackay – via Internet Archive.

- Boardman, S (1996a). "Lordship in the North-East: The Badenoch Stewarts, I. Alexander Stewart, Earl of Buchan, Lord of Badenoch". Northern Scotland. 16 (1): 1–29. doi:10.3366/nor.1996.0002. eISSN 2042-2717. ISSN 0306-5278.

- Boardman, S (1996b). The Early Stewart Kings: Robert II and Robert III, 1371–1406. East Linton: Tuckwell Press. ISBN 1 898410 43 7 – via Google Books.

- Boardman, S (1997). "Chronicle Propaganda in Fourteenth-Century Scotland: Robert the Steward, John of Fordun and the 'Anonymous Chronicle'". Scottish Historical Review. 76 (1): 23–43. doi:10.3366/shr.1997.76.1.23. eISSN 1750-0222. ISSN 0036-9241. JSTOR 25530736 – via JSTOR. (subscription required (help)).

- Boardman, S (2006). The Campbells, 1250–1513. Edinburgh: John Donald. ISBN 978-0-85976-631-9 – via Google Books.

- Boardman, SI (2004). "MacRuairi, Ranald, of Garmoran (d. 1346)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/54286. Retrieved 5 July 2011. (subscription required (help)).

- Boardman, SI (2005). "'Pillars of Community': Clan Campbell and Architectural Patronage in the Fifteenth Century". In Oram, RD; Stell, GP. Lordship and Architecture in Medieval and Renaissance Scotland. Edinburgh: John Donald. pp. 123–159. ISBN 978 0 85976 628 9 – via Questia. (subscription required (help)).

- Boardman, SI (2006). "Robert II (1316–1390)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (May 2006 ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/23713. Retrieved 6 September 2011. (subscription required (help)).

- Brown, MH (1991). Crown-Magnate Relations in the Personal Rule of James I of Scotland (1424–1437) (PhD thesis). University of St Andrews – via Research@StAndrews:FullText.

- Brown, M (2004). The Wars of Scotland, 1214–1371. The New Edinburgh History of Scotland (series vol. 4). Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 0748612386 – via Google Books.

- Caldwell, D (2008). Islay: The Land of the Lordship. Edinburgh: Birlinn.

- Campbell of Airds, A (2000). A History of Clan Campbell. Vol. 1, From Origins to Flodden. Edinburgh: Polygon at Edinburgh. ISBN 1-902930-17-7.

- Campbell of Airds, A (2004). "The House of Argyll". In Omand, D. The Argyll Book. Edinburgh: Birlinn. pp. 140–150. ISBN 1-84158-253-0.

- Cameron, C (2014). "'Contumaciously Absent'? The Lords of the Isles and the Scottish Crown". In Oram, RD. The Lordship of the Isles. The Northern World: North Europe and the Baltic c. 400–1700 AD. Peoples, Economics and Cultures (series vol. 68). Leiden: Brill. pp. 146–175. doi:10.1163/9789004280359_008. ISBN 978-90-04-28035-9. ISSN 1569-1462.

- Cathcart, A (2006). Kinship and Clientage: Highland Clanship, 1451–1609. The Northern World: North Europe and the Baltic c. 400–1700 AD. Peoples, Economics and Cultures (series vol. 20). Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978 90 04 15045 4. ISSN 1569-1462.

- Cochran-Yu, DK (2015). A Keystone of Contention: The Earldom of Ross, 1215–1517 (PhD thesis). University of Glasgow – via Glasgow Theses Service.

- Cokayne, GE; White, GH, eds. (1949). The Complete Peerage. Vol. 11. London: The St Catherine Press.

- Daniels, PW (2013). The Second Scottish War of Independence, 1332–41: A National War? (MA thesis). University of Glasgow – via Glasgow Theses Service.

- Duffy, S (2002). "The Bruce Brothers and the Irish Sea World, 1306–29". In Duffy, S. Robert the Bruce's Irish Wars: The Invasions of Ireland 1306–1329. Stroud: Tempus Publishing. pp. 45–70. ISBN 0-7524-1974-9 – via Academia.edu.

- Duncan, AAM; Brown, AL (1956–1957). "Argyll and the Isles in the Earlier Middle Ages" (PDF). Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. 90: 192–220 – via Archaeology Data Service.

- Duncan, AAM (1998) [1993]. "The 'Laws of Malcolm MacKenneth'". In Grant, A; Stringer, KJ. Medieval Scotland: Crown, Lordship and Community. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. pp. 239–273. ISBN 0-7486-1110-X.

- Ewan, E (2006). "MacRuairi, Christiana, of the Isles (of Mar)". In Ewan, E; Innes, S; Reynolds, S; Pipes, R. The Biographical Dictionary of Scottish Women: From the Earliest Times to 2004. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. p. 244. ISBN 0 7486 1713 2 – via Questia.

- Fisher, I (2005). "The Heirs of Somerled". In Oram, RD; Stell, GP. Lordship and Architecture in Medieval and Renaissance Scotland. Edinburgh: John Donald. pp. 85–95. ISBN 978 0 85976 628 9 – via Questia. (subscription required (help)).

- Grant, A (1998) [1993]. "Thanes and Thanages, from the Eleventh to the Fourteenth Centuries". In Grant, A; Stringer, KJ. Medieval Scotland: Crown, Lordship and Community. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. pp. 39–81. ISBN 0 7486 1110 X.

- "Individual(s) / Person(s): Mac Ruaidhri, constable of Toirdhealbhach O Conchobhair's Galloglasses". The Galloglass Project. n.d. Retrieved 12 April 2016.

- Lynch, M (1991). Scotland: A New History. London: Century. ISBN 0-7126-3413-4.

- McDonald, RA (1997). The Kingdom of the Isles: Scotland's Western Seaboard, c. 1100–c. 1336. Scottish Historical Monographs (series vol. 4). East Linton: Tuckwell Press. ISBN 978-1-898410-85-0.

- McLeod, W (2005) [2004]. "Political and Cultural Background". Divided Gaels: Gaelic Cultural Identities in Scotland and Ireland 1200–1650. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199247226.003.0002. ISBN 0-19-924722-6 – via Oxford Scholarship Online.

- McNamee, C (2012) [2006]. Robert Bruce: Our Most Valiant Prince, King and Lord. Edinburgh: Birlinn Limited. ISBN 978-0-85790-496-6.

- McNeill, DJ (1981). "Were Some McNeills Really MacLeans?". Society of West Highland and Island Historical Research. 15: 3–8.

- McQueen, AAB (2002). The Origins and Development of the Scottish Parliament, 1249–1329. University of St Andrews – via Research@StAndrews:FullText.

- Munro, J (1981). "The Lordship of the Isles". In Maclean, L. The Middle Ages in the Highlands. Inverness: Inverness Field Club.

- Munro, J (1986). "The Earldom of Ross and the Lordship of the Isles" (PDF). In John, J. Firthlands of Ross and Sutherland. Edinburgh: The Scottish Society for Northern Studies. pp. 59–67. ISBN 0 9505994 4 1 – via Scottish Society for Northern Studies.

- Munro, RW; Munro, J (2004). "MacDonald family (per. c.1300–c.1500)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/54280. Retrieved 5 July 2011. (subscription required (help)).

- Munro, R; Munro, J (2008). "Ross Family (per. c.1215–c.1415)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (October 2008 ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/54308. Retrieved 5 July 2011. (subscription required (help)).

- Nicholls, K (2007). "Scottish Mercenary Kindreds in Ireland, 1250–1600". In Duffy, S. The World of the Galloglass: Kings, Warlords and Warriors in Ireland and Scotland, 1200–1600. Dublin: Four Courts Press. pp. 86–105. ISBN 978-1-85182-946-0 – via Google Books.

- Oram, RD (2004). "The Lordship of the Isles, 1336–1545". In Omand, D. The Argyll Book. Edinburgh: Birlinn. pp. 123–139. ISBN 1-84158-253-0.

- Penman, M (2008). "Robert I (1306–1329)". In Brown, M; Roland, T. Scottish Kingship, 1306–1542. Edinburgh: John Donald. pp. 20–40. ISBN 9781904607823 – via Stirling Online Research Repository.

- Penman, M (2014). Robert the Bruce: King of the Scots. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-14872-5 – via Google Books.

- Penman, MA (2001). "The Scots at the Battle of Neville's Cross, 17 October 1346". Scottish Historical Review. 80 (2): 157–180. doi:10.3366/shr.2001.80.2.157. eISSN 1750-0222. ISSN 0036-9241. JSTOR 25531043 – via JSTOR. (subscription required (help)).

- Penman, MA (2005) [2004]. David II, 1329–71. Edinburgh: John Donald. ISBN 978-0-85976-603-6 – via Questia. (subscription required (help)).

- Penman, MA (2014). "The MacDonald Lordship and the Bruce Dynasty, c.1306–c.1371". In Oram, RD. The Lordship of the Isles. The Northern World: North Europe and the Baltic c. 400–1700 AD. Peoples, Economics and Cultures (series vol. 68). Leiden: Brill. pp. 62–87. doi:10.1163/9789004279469_004. ISBN 978-90-04-28035-9. ISSN 1569-1462.

- Proctor, C (2006). "MacRuairi, Amy". In Ewan, E; Innes, S; Reynolds, S; Pipes, R. The Biographical Dictionary of Scottish Women: From the Earliest Times to 2004. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. p. 243. ISBN 0 7486 1713 2 – via Questia.

- Raven, JA (2005). Medieval Landscapes and Lordship in South Uist (PhD thesis). Vol. 1. University of Glasgow – via Glasgow Theses Service.

- Roberts, JL (1999). Feuds, Forays, and Rebellions: History of the Highland Clans, 1475–1625. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 0 7486 1250 5.

- Sellar, WDH (2000). "Hebridean Sea Kings: The Successors of Somerled, 1164–1316". In Cowan, EJ; McDonald, RA. Alba: Celtic Scotland in the Middle Ages. East Linton: Tuckwell Press. pp. 187–218. ISBN 1-86232-151-5.

- Steer, KA; Bannerman, JW; Collins, GH (1977). Late Medieval Monumental Sculpture in the West Highlands. Edinburgh: Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland. ISBN 0114913838 – via Google Books.

- Stell, G (2014). "Castle Tioram and the MacDonalds of Clanranald: A Western Seaboard Castle in Context". In Oram, RD. The Lordship of the Isles. The Northern World: North Europe and the Baltic c. 400–1700 AD. Peoples, Economics and Cultures (series vol. 68). Leiden: Brill. pp. 271–296. doi:10.1163/9789004280359_014. ISBN 978-90-04-28035-9. ISSN 1569-1462.

- Tabraham, C (2005) [1997]. Scotland's Castles. London: BT Batsford. ISBN 0 7134 8943 X.

- Webster, B (2004). "Balliol, Edward (b. in or after 1281, d. 1364)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/1206. Retrieved 28 April 2012. (subscription required (help)).

- Webster, B (2011). "David II (1324–1371)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (January 2011 ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/3726. Retrieved 3 December 2015. (subscription required (help)).