Richard Bland

| Richard Bland | |

|---|---|

Richard Bland | |

| Born |

May 6, 1710 Orange County, Virginia |

| Died |

October 26, 1776 (aged 66) Williamsburg, Virginia |

| Resting place | Jordan Point Plantation, Prince George County, Virginia |

| Alma mater | College of William and Mary Edinburgh University |

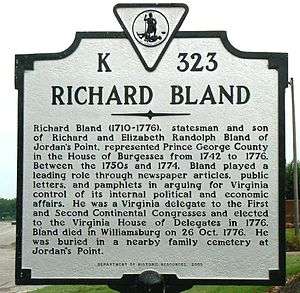

Richard Bland (May 6, 1710 – October 26, 1776), sometimes referred to as Richard Bland II or Richard Bland of Jordan's Point[1][nb 1], was an American planter and statesman from Virginia and a cousin of Thomas Jefferson. He served for many terms in the House of Burgesses, and was a delegate to the Continental Congress in 1774 and 1775.

Family and early life

His father, Richard Bland I, was a member of one of the main patriarchal First Families of Virginia, and was related to many of the others. This branch of the Bland family first came to Virginia in 1654, when the father of Richard I, Theodorick Bland of Westover(1629–1671), emigrated from London and Spain, where he had been attending to the family mercantile and shipping enterprises. Theodorick moved to Virginia to manage the family enterprises there as a result of the death of his elder brother, Edward Bland in 1653. Theodorick established Berkeley Plantation and Westover Plantation, and both survive still side by side as working plantations on the bank of the James River. He served several terms in the House of Burgesses, and was its speaker in 1660 when he married Governor Richard Bennett's daughter, Anna. Before he died in 1671 they had three sons: Theodorick (1663–1700), Richard (1665–1720), and John (1668–1746).[2][3] Not being the eldest, Richard I moved further up the river and started his own plantation on land his father had purchased in 1656, which became known as Jordan's Point Plantation near the current Jordan Point in Prince George County, Virginia. His first wife was Mary Swann, but she died without living children. In 1702 he married Elizabeth Randolph (1680–1720). They would have five children: Mary (1703) (married Henry Lee), Elizabeth (1706) (married William Beverley), Richard (1710), Anna (1711) (married Robert Munford), and Theodorick (1718) whose son, Theodorick Bland, also became a congressman and first commanded General Washington's "Virginia Cavalry." The Richard of this generation also served in the House of Burgesses. His elder brother, Theodorick II, would become the original surveyor of the towns of Williamsburg and Alexandria.

When Richard II was born on May 6, 1710 at either Jordan's Point or "Bland House" in Williamsburg, he was heir to the farm, and lived there his entire life. He inherited it early, as both his parents died just before his tenth birthday in 1720. His mother Elizabeth died on January 22, and his father Richard on April 6. His uncles, William and Richard Randolph, looked after his farm and early education and raised, as guardians, Richard and his siblings. It was likely during his young years that he developed his close relationship with his first cousin, Peyton Randolph, that would last throughout their lives, often sitting side by side during their years of service in the House of Burgesses, the Committee of Safety, and the First and Second Continental Congresses. Another of Richard's and Peyton's first cousins, Jane Randolph Jefferson, would have a son Thomas Jefferson who would follow his cousins and mentors, Richard and Peyton, to the House of Burgesses and the Continental Congresses. Richard attended the College of William and Mary then, like many of his time, completed his education in Scotland at Edinburgh University. He was trained in the law and admitted to the bar in 1746, but never offered his legal services to the public. He held an extensive library for his time, much of which was preserved by its acquisition after his death by younger cousin Thomas Jefferson and his nephew-in-law St. George Tucker and made its way to the Library of Congress as part of Jefferson's personal library donation in 1815.

Richard II married Anne Poythress (December 13, 1712 – April 9, 1758), the daughter of Colonel Peter and Ann Poythress,[4] from Henrico County, Virginia. The couple married at Jordan's Point on March 21, 1729, and made it their home. They had twelve children: Richard (1731), Elizabeth (1733), Ann Poythress(1736), Peter Randolph (1737), John (1739), Mary (1741), William (1742), Theodorick (1744), Edward (1746), Sarah (1750), Susan (1752) and Lucy (1754). See "The Bland Papers" of Col. Theodorick Bland published by Charles Campbell. Richard would marry twice after Anne died (to Martha Macon and Elizabeth Blair), but without any more children. ("An Inquiry into the Rights of the British Colonies" colonial book, originally printed by Alexander Purdie, states that Bland's second wife may have been either Elizabeth Harrison or Elizabeth Bolling, the daughter of John Bolling Jr. and Elizabeth Blair.[5])

Early political career

Bland served as a Justice of the Peace in Prince George County, and was made a militia officer in 1739. In 1742 he was first elected to the Virginia House of Burgesses, where he served successive terms until it was suppressed during the American Revolution. Bland's thoughtful work made him one of its leaders, although he was never a strong speaker. He frequently served on committees whose role was to negotiate or frame laws and treaties. Sometimes described as a bookish scholar as well as farmer, Bland read law, and was admitted to the Virginia bar in 1746. He did not practice before the courts, but collected legal documents and became known for his expertise in Virginia and British history and law.[6]

Bland often published pamphlets (frequently anonymously), as well as letters. His first widely distributed public paper came as a result of the Parson's Cause, which was a debate from 1759 to 1760 over the established church and the kind and rate of taxes used to pay the Anglican clergy. His pamphlet A Letter to the Clergy on the Two-penny Act was printed in 1760, as he opposed increasing pay and the creation of a bishop for the colonies.

An early critic of slavery, though a slaveholder, Bland stated "under English government all men are born free", which prompted considerable debate with John Camm, a professor at Bland's alma mater, the College of William and Mary.[7]

Colonial rights advocate, An Inquiry into the Rights of the British Colonies

When the Stamp Act created controversy throughout the colonies, Bland thought through the entire issue of parliamentary laws as opposed to those that originated in the colonial assemblies. While others, particularly James Otis, get more credit for the idea of "no taxation without representation", the full argument for this position seems to come from Bland. In early 1766, he wrote An Inquiry into the Rights of the British Colonies. It was published in Williamsburg and reprinted in England.

Richard's Inquiry examined the relationship of the king, parliament, and the colonies. While he concluded that the colonies were subject to the crown, and that colonists should enjoy the rights of Englishmen, he questioned the presumption that total authority and government came through parliament and its laws. Thomas Jefferson described the work as "the first pamphlet on the nature of the connection with Great Britain which had any pretension to accuracy of view on that subject.... There was more sound matter in his pamphlet than in the celebrated Farmer's letters."

In 1774, the Virginia Burgesses sent him to the First Continental Congress in Philadelphia. A number of the views he had expressed in his Inquiry found their way into that first session of the Congress, in its Declaration of Rights.

Founding the state of Virginia

In 1775, as revolution neared in Virginia, the Virginia Convention replaced the Burgesses and the Council as a form of ad-hoc government. That year he met with the Burgesses and with the three sessions of the convention. In March, after Patrick Henry's "Give me liberty or give me death" speech, he was still opposed to taking up arms. He believed that reconciliation with England was still possible and desirable. Nevertheless, he was named to the committee of safety and re-elected as a delegate to the national Congress. In May he travelled to Philadelphia for the opening of the Second Continental Congress, but soon returned home, withdrawing due to the poor health and failing eyesight of old age. However, his radicalism had increased, and by the Convention's meeting in July, he proposed hanging Lord Dunmore, the royal governor.

In the first convention meeting of 1776, Richard Bland declined a re-election to the Third Continental Congress, citing his age and health. However, he played an active role in the remaining conventions. He served on the committee which drafted Virginia's first constitution in 1776. When the House of Delegates for the new state government was elected, he was one of the members.

He died while serving in the new House, on October 26, 1776 at Williamsburg, Virginia. In November he was taken home one last time, and was buried in the family cemetery at Jordan's Point in Prince George County.[8] Bland County and Richard Bland College, junior college of the College of William and Mary in Petersburg, Virginia, are named in his honour.[9]

Ancestry and family ties

| Ancestors of Richard Bland | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Bland's paternal uncle was the surveyor Theodorick Bland.[10] Other familial connections:

- As a grandson of William Randolph of Turkey Island, Richard's cousins included Peyton Randolph, Thomas Jefferson, and Edmund Randolph (the first United States Attorney General).[11]

- His sister Mary Bland married Col. Henry Lee I and was grandmother of Henry "Light Horse Harry" Lee, who was the father of Confederate General Robert E. Lee.[12]

- His great-grandfather Richard Bennett was the first and only elected Governor of Virginia (1652–1655) before the Revolution. Richard Bennett, for whom Richard Bland was named, was the Puritan governor of Virginia during the English Reformation who worked for religious tolerance in Virginia and Maryland and restored peace with the Native Americans who had been plundered by the former governor appointed by the King.[13]

- His cousin Giles Bland, named after his grandfather Giles Green, was a first lieutenant to Nathaniel Bacon in the first American revolution aka Bacon's Rebellion. For his role in the Rebellion, Giles was hung illegally by Governor Berkely, who reportedly held in his pocket the King's pardon for Giles at the time of the hanging.[14][15] Generations later, cousins of Giles and Nathaniel (neither left direct descendants) would join the two families by the marriage of Peter Randolph Bland (son of Capt. Edward Bland and grandson of Richard Bland II) and Susanna Parke Bacon, who became the parents of, among others, Edward Parke Bland, a physician of St. Louis and St. Clair County, Illinois, and of Colin Bland aka Colin de Bland, a young lawyer who served in the Texas War of Independence and the Lamar government of Texas and who helped settle early Texas (sometimes with his pistol).

- His grand-nephew John Randolph of Roanoke served as U.S. Congressman and as U.S. Senator.

- His great-grandmother Susan Dublere was the daughter of a prominent merchant who was a French Huguenot refugee living in Hamburg, Germany.

- His cousin Theodorick Bland, served as Chancellor of Maryland and United States District Court for the District of Maryland. Chancellor Theodorick Bland was the son of Theodorick Bland the "Tory" (but perhaps a loyal American spy?) and Sarah Fitzhugh, daughter of Henry Fitzhugh and great-granddaughter of William Fitzhugh. These two Theodoricks are descended from Theodorick I's son John, who remained in England after returning there for his education and lived in Scarborough, England.

- His nephew, Col. Theodorick Bland, commanded General George Washington's first Virginia cavalry, the Continental Light Dragoons aka "the Virginia Horse", and was elected to the First United States Congress where he served until his death in 1790, the first member of the new U.S. Congress to die in office.

- His grandfather Theodorick Bland of Westover served as Speaker of the 1660 House of Burgesses session and, in this role, presided over the House during the transition from the Cromwell Protectorate to the restored government of Charles II. Theodorick Bland I was the son-in-law of the Restoration Governor, Richard Bennett (the popular, elected Quaker governor). Theodorick served on the Governor's Council from 1664 until his death in 1671. His son, Theodorick II was the original surveyor of the towns of Williamsburg and Alexandria.

- His great great grandson, John Randolph Bland, founded in 1896 the United States Fidelity and Guaranty Company in Baltimore MD. See Men of Mark in Maryland and Baltimore: Biography by Lewis Historical Publishing Co

- His grandfather's brother Edward Bland, a merchant in early Virginia, explored western Virginia and the Carolinas for possible settlement and development, then published his account The Discovery of New Brittaine in 1651, London. His work is noted for opening the Carolinas to further exploration and archiving details of the Native American tribes he encountered, which is still relied on today to reconstruct Native history in the region. It was reprinted in 1873 and 1966.

- His ancestor William de Blande, "did good service to King Edward III in his wars in France, in the company of John of Gaunt, Earl of Richmond [as his standard bearer], and had a pardon for the death of John de Vale, dated the 4th of June, in the 34th year of that King's reign, 1361."

- His cousin the Rev John Bland, Vicar of Staple and Adisham, was among the Canterbury Martyrs burned at the stake in 1555 by Queen Mary. He was accused of heresy, imprisoned, re-arrested, then after ten months in prison was led to the stake which he shared with three others. The Rev Bland had been tutor to Edwin Sandys, Bishop of London and Archbishop of York.

- Another Bland relative documented in family history was a young English merchant in Calais who purportedly was the first to warn Queen Elizabeth I's government of the gathering of the Spanish Armada. This young Bland was eventually freed from a Spanish prison by his friends and made his way home.

Other descendants of Bland include Roger Atkinson Pryor.[16]

Notes

- ↑ Richard Bland's father, Richard Bland, is also referred to in some sources as Richard Bland of Jordan's Point.

References

- ↑ Tyler, Lyon Gardiner, ed. (1915). "Fathers of the Revolution". Encyclopedia of Virginia Biography. II. New York: Lewis Historical Publishing Company. p. 4.

- ↑ Richard Bland. "An Inquiry into the Rights of the British Colonies". Appeals Press, Inc., Richmond, Virginia.

- ↑ Theodorick Bland (1840). Charles Campbell, ed. The Bland Papers: Being a Selection from the Manuscripts of Colonel Theodorick Bland, Jr. E. & J.C. Ruffin. p. xxviii.

- ↑ This Ann's maiden name is uncertain, however a cryptic entry in the Secret Diaries of Wm. Byrd records Col. Peter Poythress as having married in 1712, Ann B-k-r (or B-r-k).

- ↑ Bland, Richard (1922) [1766]. "Introduction". In Swem, Earl Gregg. An Inquiry into the Rights of the British Colonies. Richmond, Virginia: William Parks Club Publications. p. v.

- ↑ http://www.rbc.edu/library/specialcollections/pdf_files/bland_unveiling_speech.pdf

- ↑ Gary B. Nash, The Unknown American Revolution: The Unruly Birth of Democracy and the Struggle to Create America (New York: Viking Penguin 2005) pp. 64–65. citing Richard Bland, The Colonel Dismounted: Or the Rector Vindicated in a Letter Addressed to His Reverence Containing a Dissertation upon the Constitution of the Colony (1764); John Camm, Critical Remarks on a Letter Ascribed to Common Sesce (Williamsburg, VA: Joseph Boyle, 1765) quoted in Bernard Bailyn, Ideological Origins, pp. 235–36.

- ↑ Richard Bland at Find a Grave

- ↑ "Richard Bland – Virginia Statesman and Champion of Public Rights". Richard Bland College. Retrieved 2007-11-27.

- ↑ Hunter, Joseph (1895). "Bland". In Clay, John W. Familiae Minorum Gentium. II. London: The Harleian Society. pp. 421–27.

- ↑ Robert Isham Randolph, The Randolphs of Virginia, A Compilation of the Descendants of William Randolph of Turkey Island and his wife, Mary Isham of Bermuda Hundred 1936

- ↑ Paul C. Nagel, The Lees of Virginia: Seven Generations of an American Family 1991, p. 40.

- ↑ Boddie, John Bennett (1973). Seventeenth Century Isle of Wight County, Virginia. Genealogical Publishing Company. pp. 79–80. ISBN 0-8063-0559-2.

- ↑ Billings, Warren M. "Giles Bland (bap. 1647–1677)". Encyclopedia Virginia. Retrieved 19 August 2015.

- ↑ Webb, Stephen (1995). 1676: The End of American Independence. Syracuse University Press. pp. 50–53. ISBN 0815603614. Retrieved 19 August 2015.

- ↑ Sons of the American Revolution (1894). "Roll of Members". Yearbook. The Republic Press. p. 198.

External links

- United States Congress. "Richard Bland (id: B000543)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- Richard Bland at Encyclopedia Virginia

- Richard Bland, Revolutionary Philosopher Press Release by Marjorie Solenberger (July 1994)

- Richard, 1710-1776 Richard Bland on the Internet Archive

- An Inquiry into the Rights of the British Colonies at the Internet Archive